Shimul A. Shah

DEFINITION

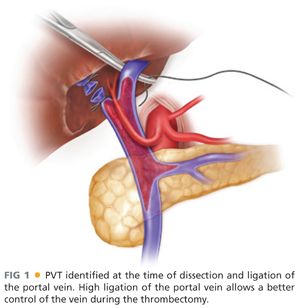

■ Portal vein thrombosis (PVT) refers to the thrombotic occlusion of the portal lumen, which can affect the intrahepatic and the extrahepatic venous tracts (FIG 1).

■ Although many classifications of PVT exist, its importance lies in the surgical approach employed, which is determined by the extent of thrombosis, and the presence/adequacy of collateral vessels that can potentially be used for extraanatomic reconstructions to establish portal venous flow.

INCIDENCE

■ The incidence of PVT in patients with end-stage liver disease (ESLD) varies from 5% to 15% with up to half of all patients diagnosed at surgery. The majority of patients have partial thrombosis.

■ The incidence of thrombosis occurring while on the liver transplant waiting list is 7% for a mean waiting time of 12 months.

RISK FACTORS

■ In noncirrhotic patients, PVT is most often related to prothrombotic states (myeloproliferative neoplasms and/or inherited coagulation disorders).

■ In cirrhotic patients, portal hemodynamics is the main factor leading to thrombosis. The characteristic parenchymal changes of cirrhosis as well as changes in vasoreactivity result in increased intrahepatic vascular resistance and reduced portal flow. Both pro- and anticoagulant factors are decreased in cirrhosis, resulting in a fragile compensated hemostatic balance that may easily tip toward a hypo- or hypercoagulable situation, causing either hemorrhagic or thrombotic complications.

■ Low platelet count seems to be an independent predisposing factor for PVT in cirrhosis, although it could be a proxy for the degree of portal vascular resistance (portal hypertension).

■ Cirrhotic patients with PVT, compared to those without PVT, have an increased prevalence of factor V Leiden, methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism, and prothrombin gene mutations, the latter being particularly frequent. However, only the mutation 20210 of the prothrombin gene is independently associated with PVT.

■ PVT is more common in male; patients with autoimmune, chronic active hepatitis; cryptogenic cirrhosis; alcoholic liver disease; and patients with previous treatment of portal hypertension–related bleeding (sclerotherapy, surgery, and splenectomy). The presence of at least one risk factor, including male sex, previous treatment of portal hypertension, Child C class, and the presence of alcoholic liver disease, increases the rate of PVT from 6.6% (absence of risk factors) to 12.5%.

■ Presence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) constitutes a risk factor for PVT. Tumor invasion involving the branches and/or the trunk of the portal vein is a possible source of portal vein obstruction in patients with HCC. Macroscopic vascular invasion by the tumor is a definitive contraindication for transplantation. Therefore, in candidates for transplantation with HCC and portal vein obstruction, a clear distinction between tumor invasion and thrombosis should be made.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ Doppler ultrasonography (US) and multiphasic (arterial and portal) helical computed tomography (CT) are the investigation of choice.

■ Doppler US is highly accurate at detecting thrombosis involving the trunk of the portal vein and in intrahepatic branches. It provides additional information concerning portal flow and its direction. Doppler US may be recommended every 3 months during waiting time, whenever possible.

■ CT clearly displays the superior mesenteric vein (SMV), spontaneous portosystemic shunts, renal veins, and the inferior vena cava (IVC).

■ Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an alternative to CT in patients with impaired renal function or depending on local expertise and preference. However, the definition is lower than that of CT, especially in patients with tense ascites.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

■ The main objective of treatment is to achieve at least partial recanalization so that portal flow to the graft can be restored through conventional end-to-end portal vein anastomosis. Also, to prevent further extension of the thrombus during waiting time, especially to the SMV.

Anticoagulation

■ Anticoagulation in cirrhosis is justified by the preserved balance between pro- and anticoagulant factors, even when coagulation factors are decreased. With partial thrombosis, complete recanalization may be achieved in 40% to 75% of patients, whereas less than 10% experience an extension of the thrombus. The rate of recanalization is significantly higher in patients receiving anticoagulation than in control patients who do not. However, no good data is available regarding bleeding risks in cirrhotic patients who could be at risk of excessive anticoagulation. Anticoagulation is not considered effective for chronic PVT in cirrhotic patients.

Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt

■ The objective of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is to recanalize the portal vein and, subsequently, prevent rethrombosis by restoring portal flow through a low-resistance shunt. It clearly appears that the feasibility of TIPS varies according to the extent of thrombosis. Technical failure may be related to the absence of visibility of intrahepatic branches of the portal vein, transformation of the portal vein into a fibrous cord, and extension of the thrombus to the SMV. TIPS may be feasible in some patients with cavernoma. Ideally, TIPS insertion and recanalization might be associated with disrupture of the thrombus and mechanical thrombectomy.

TECHNIQUES

THROMBENDOVENECTOMY

■ The portal vein thrombus is usually organized with a significant fibrotic component strongly attached to the intima. An effective approach in these cases is a thrombendovenectomy. This technique is similar to a thromboendarterectomy: The intima is removed together with the clot.1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree