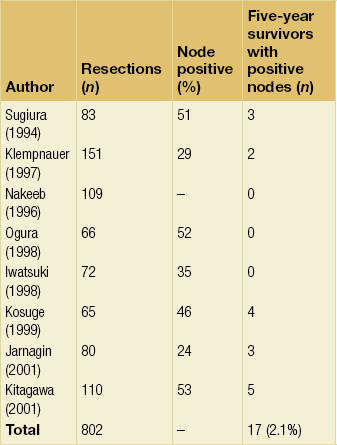

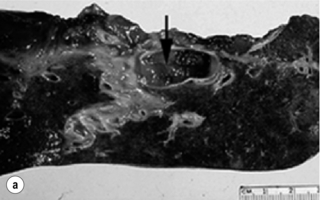

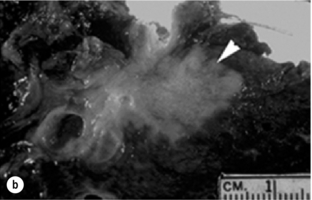

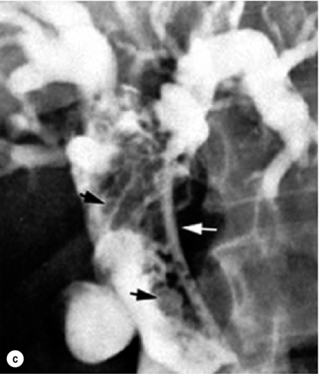

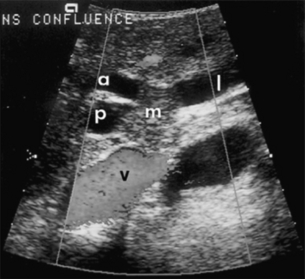

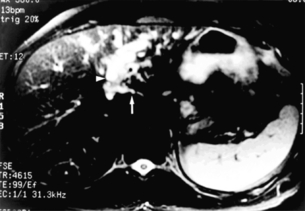

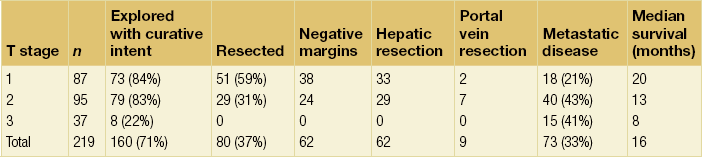

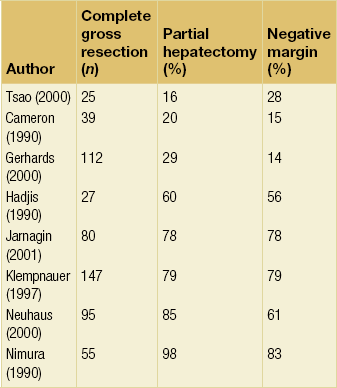

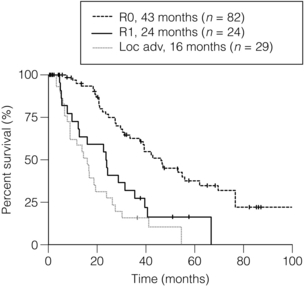

12 Malignant lesions of the biliary tract, specifically arising from the gallbladder or biliary epithelium, are rare and only account for approximately 15% of hepatobiliary neoplasms. Gallbladder cancer is the most common site, accounting for 60% of all biliary tract cancers, while the remaining 40% are distributed throughout the extrahepatic and intrahepatic biliary tree, with the next most common site occurring at the extrahepatic biliary confluence.1 Complete resection is associated with the best survival and is the most effective therapy, but is usually only possible in a minority of patients. Palliating the effects of biliary obstruction is thus often the primary therapeutic goal. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy have not been proved to reduce the incidence of recurrence after resection nor to improve survival. Unfortunately, due to the rarity of these tumours and their frequently advanced stage at presentation, randomised prospective trials assessing different treatment regimens have not been performed. This chapter focuses on the current management of cholangiocarcinoma, specifically hilar, intrahepatic and distal bile duct cancers, as well as gallbladder carcinoma. Cholangiocarcinoma is an uncommon cancer with an incidence of 1–2 per 100 000 in the USA and approximately 5000–8000 new cases diagnosed each year.2 Overall, men are affected 1.5 times as often as women and the majority of patients are greater than 65 years of age, with the peak incidence occurring in the eighth decade of life.2 Cholangiocarcinomas are classified according to their site of origin within the biliary tree, with those involving the biliary confluence, or hilar cholangiocarcinoma, being the most common and accounting for approximately 60% of all cases.3–6 Twenty to thirty per cent of cholangiocarcinomas originate in the distal bile duct, while approximately 10% arise within the intrahepatic biliary tree.7–9 Rarely, patients will present with multifocal or diffuse involvement of the biliary tree.10 More recent studies have documented the marked increase in incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, which may become the more common variant (see below).11–14 The vast majority of patients with unresectable bile duct cancer die within 6 months to 1 year of diagnosis, usually from liver failure or infectious complications secondary to biliary obstruction.3,15–17 The prognosis is often worse for hilar lesions and better for lesions of the distal bile duct, which probably reflects the greater complexity and difficulty in effectively managing proximal lesions, more so than differences in tumour biology. Indeed, it has been shown that location within the biliary tree (proximal versus distal) has no impact on survival provided that complete resection is performed.4 That being said, patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma often present with advanced lesions due to the absence of symptoms, such as jaundice or biliary tract-related sepsis. Most cases of cholangiocarcinoma in the West are sporadic and have no obvious risk factors. However, certain pathological conditions are associated with an increased incidence, the most common of which is primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). The majority of patients (70–80%) with PSC have associated ulcerative colitis, while a minority of patients with ulcerative colitis develop PSC.18 The natural history of PSC is variable, and the true incidence of cholangiocarcinoma is unknown. In a Swedish series of 305 patients followed over several years, 8% of patients eventually developed cancer. On the other hand, occult cholangiocarcinoma has been reported in up to 40% of autopsy specimens and in up to 36% of liver explants from patients with PSC.18,19 Patients with cholangiocarcinoma associated with PSC are often not candidates for resection because of multifocal disease or severe underlying hepatic dysfunction. Congenital biliary cystic disease (i.e. choledochal cysts) is also associated with an increased risk for the development of biliary tract cancer.20,21 This appears to be related to the finding that these patients have an abnormal choledochopancreatic duct junction, which predisposes to reflux of pancreatic secretions into the biliary tree, chronic inflammation and bacterial contamination.21–24 A similar mechanism may also explain the increased incidence of cholangiocarcinoma reported in patients subjected to transduodenal sphincteroplasty or endoscopic sphincterotomy. In a series of 119 patients subjected to this procedure for benign conditions, Hakamada et al. found a 7.4% incidence of cholangiocarcinoma over a period of 18 years.25 Hepatolithiasis is a well-known risk factor for the development of cholangiocarcinoma in Japan and parts of southeast Asia, arising in 10% of those affected. Chronic portal bacteraemia and portal phlebitis lead to intrahepatic pigment stone formation, obstruction of intrahepatic ducts, and recurrent episodes of cholangitis and stricture formation.26,27 This recurrent inflammatory state is likely the main contributing factor to cholangiocarcinogenesis. Biliary parasites (Clonorchis sinensis, Opisthorchis viverrini) are also prevalent and endemic in parts of Asia, such as Thailand, and are similarly associated with an increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma.19 Finally, exposure to several radionuclides and chemical carcinogens, such as thorium, radon, nitrosamines, dioxin and asbestos, may also increase the risk of cholangiocarcinoma. Three macroscopic subtypes of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma are described: sclerosing, nodular and papillary, of which the first two are often combined into one (i.e. nodular-sclerosing) since features of both types are often seen together.28 The histopathology is distinct between cholangiocarcinomas arising from the extrahepatic and intrahepatic biliary system. For extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, the overwhelming majority is adenocarcinoma, and most are firm, sclerotic tumours with a paucity of cellular components within a dense fibrotic, desmoplastic background. As a consequence, a non-diagnostic preoperative biopsy is not uncommon.2,28,29 Papillary tumours represent a less common morphological variant, accounting for approximately 10% of tumours arising from the extrahepatic biliary tree.28 Papillary tumours are soft and friable, may be associated with little transmural invasion, and are characterised by a mass that expands rather than contracts the duct (Fig. 12.1). Although papillary tumours may grow to significant size, they often arise from a well-defined stalk, with the bulk of the tumour mobile within the ductal lumen. Despite this histological variant being the minority of cases, recognition of this entity is important since they are more often resectable and have a more favourable prognosis than the other types.19,30 Figure 12.1 Gross and cholangiographic appearance of a papillary cholangiocarcinoma (a,c) and a nodular-sclerosing tumour (b,d). In (a) and (c), note that the papillary tumour occupies the lumen and expands the duct (black arrow). A biliary stent is visualised (white arrow). In (b) and (d), the nodular-sclerosing variant constricts the lumen, nearly obliterating it (white arrow). Reprinted with permission from Blumgart LH (ed.) Surgery of the liver, biliary tract, and pancreas, 4th edn. Elsevier Saunders, 2006. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma is typically highly invasive within the hepatoduodenal ligament. Direct invasion of the liver or perihepatic structures, such as the portal vein or hepatic artery, is a common feature and has important clinical implications regarding resectability.28 The liver is also a common site of metastatic disease, as are the regional lymph node basins, but spread to distant extra-abdominal sites is uncommon at initial presentation.3,31 These tumours also have a propensity for longitudinal spread along the duct wall and periductal tissues, which is an important pathological feature of cholangiocarcinomas as it pertains to the margin of resection.28 There may be substantial extension of tumour beneath an intact epithelial lining, as much as 2 cm proximally and 1 cm distally, thus predisposing to a radiographic underestimation of tumour extent.32 This predilection for submucosal extension underscores the difficulty in achieving a complete resection. Frozen section analysis of the duct margin during operation may be helpful in this regard but caution is necessary when interpreting the results. Indeed, the authors recently analysed their experience with intraoperative frozen sections and found a substantial false-negative rate. In addition, the benefits of extending the resection with a positive frozen section result were questionable.33 Gross examination of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma reveals a grey scirrhous mass, often infiltrative into the liver parenchyma.34 These tumours are adenocarcinomas and the diagnosis of intrahepatic or peripheral cholangiocarcinoma should be considered in all patients presenting with a presumptive diagnosis of metastatic adenocarcinoma with an unknown primary, particularly in the setting of a large, solitary hepatic mass. A small number show different patterns with focal areas of papillary carcinoma with mucous production, signet-ring cells, squamous cell, mucoepidermoid and spindle cell variants.35 The Liver Cancer Study group of Japan established a subclassification of these tumours based on morphology: (1) mass forming type; (2) periductal infiltrating type; (3) intraductal growth type.36 Although some studies have suggested a correlation with outcome based on morphological subtype, this classification scheme has not gained wide acceptance. Positive immunohistochemical staining usually includes carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and tumour markers CA50 and CA19-9. K-ras mutations have also been detected in up to 70% of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas, although the frequency of this mutation is quite variable.37,38 Metastatic disease at the time of exploration is not an infrequent finding. Tumours with both hepatocellular and cholangiocellular differentiation (combined tumours) are rare but well described. Their clinical behaviour more closely approximates that of cholangiocarcinoma than hepatocellular carcinoma, and they tend to display aggressive biology.39 Clinical presentation and diagnosis The early symptoms of hilar cholangiocarcinoma are often non-specific, with abdominal pain, discomfort, anorexia, weight loss and/or pruritus seen in about one-third of patients.6,19,40,41 Most patients present with jaundice or incidentally discovered abnormal liver function tests. Pruritus may precede jaundice by some weeks, and this symptom should prompt an evaluation, especially if associated with abnormal liver function tests. Patients with papillary tumours of the hilus may give a history of intermittent jaundice, perhaps due to the ball-valve effect of a pedunculated mass within the lumen or, more likely, small fragments of tumour having passed into the common bile duct. Clinical findings are often non-specific but may provide some useful information. Jaundice is usually obvious, and patients with pruritus often have multiple excoriations of the skin. The liver may be enlarged and firm as a result of biliary tract obstruction. The gallbladder is usually decompressed and non-palpable with hilar obstruction. Thus, a palpable gallbladder suggests a more distal obstruction or an alternative diagnosis. Rarely, patients with long-standing biliary obstruction and/or portal vein involvement may have findings consistent with portal hypertension. In patients with no previous biliary intervention, cholangitis is rare at initial presentation, despite a 30% incidence of bacterial contamination.42,43 Endoscopic or percutaneous instrumentation significantly increases the incidence of bacterial contamination and the subsequent risk of clinical infection. In fact, the incidence of bacterobilia approaches 100% after endoscopic biliary intubation, thus making cholangitis more common.43 It should be noted that bacterial contamination of the biliary tract in partial obstruction is not always clinically apparent. The presence of overt or subclinical infection at the time of surgery is a major source of postoperative morbidity and mortality. Thus, endoscopic and percutaneous intubations are both associated with greater morbidity and mortality following surgical resection or palliative bypass for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. In an analysis of 71 patients who underwent either resection or palliative biliary bypass for proximal cholangiocarcinoma, all patients stented endoscopically and 62% of those stented percutaneously had bacterobilia. Postoperative infectious complications were doubly increased in patients stented before operation compared to non-stented patients, while non-infectious complications were equal in both groups.43 Enterococcus, Klebsiella, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus viridans and Enterobacter aerogenes are the most common organisms, and this spectrum of bacteria must be considered when administering perioperative antibiotics; it is imperative to take intraoperative bile specimens for culture in order to guide selection of postoperative antibiotic therapy. While gallstones or even common bile duct stones may coexist with bile duct cancer, in the absence of certain predisposing conditions (e.g. PSC, recurrent pyogenic cholangitis (previously referred to as Oriental cholangiohepatitis)), it is uncommon for choledocholithiasis to cause obstruction at the biliary confluence. Furthermore, the degree of bilirubin elevation tends to be higher (e.g. 10–18 mg/dL) for malignant obstruction compared to benign stone disease (e.g. 2–10 mg/dL). That being said, other conditions may mimic hilar cholangiocarcinoma on imaging studies, such as benign idiopathic focal stenosis of the hepatic ducts (malignant masquerade), Mirizzi’s syndrome resulting from a large stone impacted in the neck of the gallbladder, and gallbladder cancer.44 Nevertheless, it is imperative to fully investigate and delineate the level and nature of any obstructing lesion causing jaundice to avoid missing the diagnosis of carcinoma. However, the histopathological diagnosis of hilar cholangiocarcinoma is often not made until the specimen is removed at operation. As mentioned previously, due to the dense desmoplastic reaction associated with the sclerosing variant of cholangiocarcinoma, non-diagnostic preoperative biopsies or brushings are the usual clinical scenario. In the authors’ view, histological confirmation of malignancy is not mandatory prior to exploration. With no prior suggestive history (i.e. prior biliary tract operation, PSC, hepatolithiasis), the finding of a focal stenotic lesion combined with the appropriate clinical presentation is sufficient for a presumptive diagnosis of hilar cholangiocarcinoma, which is correct in most instances.45 Furthermore, the alternative conditions that one may encounter are often best assessed and treated at operation. It is dangerous to rely entirely on a negative result from a needle biopsy or biliary brush cytology, since they are often misleading, particularly in the face of compelling radiographic evidence of malignant disease.46 The use of spy glass technology via endoscopic guidance has facilitated direct visualisation of the bile duct lumen and allows for targeted biopsies of the affected area. Direct cholangiography: Cholangiography demonstrates the location of the tumour and the extent of biliary disease, both of which are critical in surgical planning. Although endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) may provide helpful information, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) displays the intrahepatic bile ducts more reliably and has been the preferred approach. However, there is often a knee-jerk reflex to proceed with invasive cholangiography before a complete radiographic assessment has been made, which can lead to unnecessary patient morbidity and infectious complications. Computed tomography: Cross-sectional imaging provided by CT remains an important study for evaluating patients with biliary obstruction and can provide valuable information regarding the level of obstruction, vascular involvement and liver atrophy. As portal venous inflow and bile flow are important in the maintenance of liver cell size and mass, segmental or lobar atrophy may be evident on CT that would suggest portal venous occlusion or biliary obstruction.47 CT angiography is particularly helpful for assessing portal venous and hepatic arterial involvement. However, CT imaging tends to underestimate the proximal extent of tumour within the bile duct and is thus not ideal as the primary determinant of resectability.48 Duplex ultrasonography: Ultrasonography is a non-invasive, but operator dependent, study that often precisely delineates the level of the tumour within the bile duct (Fig. 12.2). It can also provide information regarding tumour extension within the bile duct and in the periductal tissues.49–51 In a series of 19 consecutive patients with malignant hilar obstruction, ultrasonography with colour spectral Doppler technique was equivalent to angiography and CT portography in diagnosing lobar atrophy, level of biliary obstruction, hepatic parenchymal involvement and venous invasion.51 Duplex ultrasonography is particularly useful for assessing portal venous invasion. In a series of 63 consecutive patients from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), duplex ultrasonography predicted portal vein involvement in 93% of cases with a specificity of 99% and a 97% positive predictive value. In the same series, angiography with CT angio-portography had a 90% sensitivity, 99% specificity and a 95% positive predictive value.52 Figure 12.2 Ultrasonographic view of a hilar cholangiocarcinoma showing a papillary tumour (m) extending into the right anterior (a) and posterior (p) sectoral ducts and the origin of the left duct (l). The adjacent portal vein (v) is not involved and has normal flow. Reprinted with permission from Blumgart LH (ed.) Surgery of the liver, biliary tract, and pancreas, 4th edn. Elsevier Saunders, 2006. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP): In the authors’ practice, MRCP has largely replaced endoscopic and percutaneous cholangiography to assess biliary tumour extent in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Several studies have demonstrated its utility in evaluating patients with biliary obstruction.53–56 MRCP may not only identify the tumour and the level of biliary obstruction, but may also reveal obstructed and isolated ducts not appreciated at endoscopic or percutaneous study. By virtue of being an axial imaging modality, MRCP has further advantages over standard cholangiography by also providing information regarding the patency of hilar vascular structures, the presence of nodal or distant metastases, and the presence of lobar atrophy (Fig. 12.3). Furthermore, because it does not require biliary intubation, it is not associated with the same incidence of bacterobilia and infectious complications that is frequently associated with standard cholangiography.43 Figure 12.3 Cross-sectional MRCP from a patient with hilar cholangiocarcinoma extending into the left hepatic duct and left lobe atrophy. The bile ducts appear white. The left lobe is small with dilated and crowded ducts (arrowhead). The principal caudate lobe duct, seen joining the left hepatic duct, is also dilated (arrow). Reprinted with permission from Blumgart LH (ed.) Surgery of the liver, biliary tract, and pancreas, 4th edn. Elsevier Saunders, 2006. The preoperative evaluation must address four critical determinants of resectability: extent of tumour within the biliary tree, vascular invasion, hepatic lobar atrophy and the presence of metastatic disease.3 The presence of lobar atrophy is often overlooked; however, its importance in determining resectability cannot be overemphasised, since it implies portal venous involvement, suggests a more locally advanced lesion, and compels the surgeon to perform a partial hepatectomy, if the tumour is indeed resectable.47 While long-standing biliary obstruction may cause moderate atrophy, concomitant portal venous compromise results in rapid and severe atrophy of the involved segments. Appreciation of gross atrophy on preoperative imaging is important since it often influences both operative and non-operative therapy.47 If the tumour is not resectable, percutaneous biliary drainage through an atrophic lobe, unless necessary to control sepsis, should be avoided since it will not effect a reduction in bilirubin level. Atrophy is apparent on cross-sectional imaging as a small, often hypoperfused lobe with crowding of the dilated intrahepatic ducts (Fig. 12.3). Tumour involvement of the portal vein is usually present if there is compression/narrowing, encasement or occlusion seen on imaging studies.3,57 The staging systems currently used for hilar cholangiocarcinoma do not account fully for all of the tumour-related variables that influence resectability, namely biliary tumour extent, lobar atrophy and vascular involvement. The modified Bismuth–Corlette classification stratifies patients solely based on the extent of biliary duct involvement by tumour.58 Although useful to some extent, it is not indicative of resectability or survival. Similarly, the previous AJCC T-stage system (sixth edition) was based largely on pathological criteria and had little applicability for preoperative staging. The ideal staging system should accurately predict resectability and the likelihood of associated metastatic disease, and also correlate with survival. The authors have proposed such a preoperative staging system.3,57 This staging system places the finding of portal venous involvement and lobar atrophy into the proper context for determining resectability, especially when partial hepatectomy is an important component of the operative approach (Table 12.1). For example, a tumour with unilateral extension into second-order bile ducts that is associated with ipsilateral portal vein involvement and/or lobar atrophy would still be considered potentially resectable, while such involvement on the contralateral side would preclude a resection. The authors have found that this staging system correlated well with resectability, the likelihood of associated distant metastatic disease, and median survival (Table 12.2).57 Independent confirmation of the utility of this classification scheme (the Blumgart clinical staging system) was recently reported in a series of 85 patients from China.59 The authors’ criteria for unresectability are detailed in Box 12.1. This staging scheme is now incorporated in the seventh edition of the AJCC staging system for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Table 12.1 Proposed T-stage criteria for hilar cholangiocarcinoma Reprinted with permission from Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP et al. Staging, resectability, and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2001; 234:507–19. Table 12.2 Resectability, incidence of metastatic disease, and survival stratified by T stage Reprinted with permission from Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP et al. Staging, resectability, and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2001; 234:507–19. Orthotopic liver transplantation has been attempted for unresectable hilar tumours. Klempnauer et al. reported four long-term survivors out of 32 patients who underwent transplantation for hilar cholangiocarcinoma.60 The same group also reported a 17.1% 5-year survival for their overall transplant group.61 Comparable results were reported by Iwatsuki et al.62 The results of transplantation have previously not been sufficiently adequate to justify its use, and most centres now do not perform liver transplantation for cholangiocarcinoma. More recently, data from the Mayo Clinic have emerged suggesting good results with transplantation in highly selected patients with low-volume unresectable disease and combined with an intensive pre-transplant treatment regimen.63,64 Although the data are compelling, routine use of vascular resection, even when there is no obvious tumour infiltration, will likely lead to higher perioperative morbidity; this approach would therefore seem applicable to a very small proportion of patients. Resection is the most effective therapy for patients with potentially resectable tumours, with the primary objective being complete removal of all gross disease with clear histological margins (R0 resection). The importance of an R0 resection is clear from previous studies showing that incomplete (R1 or R2) resections do not improve survival beyond that of patients with unresectable tumours (Fig. 12.4).3,57 There is now overwhelming evidence to support the observation that partial hepatectomy, combined with excision of the extrahepatic biliary system, is usually required to achieve this goal (Table 12.3). A review of several series in the literature shows a close correlation between the proportion of patients who underwent concomitant partial hepatectomy and the proportion of R0 resections achieved. For tumours extending into the left hepatic duct, en bloc caudate lobectomy is usually necessary to obtain a complete resection, since the principal biliary drainage of the caudate lobe is via the left hepatic duct.65,66 A dilated caudate duct, suggesting tumour involvement, may occasionally be visualised on preoperative imaging (Fig. 12.3). Table 12.3 Summary of selected studies showing the relationship between the rate of partial hepatectomy and proportion of negative histological margins achieved Figure 12.4 Survival curves after resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. R0 indicates complete resection with histologically negative resection margins (median survival 43 months). R1 indicates histologically involved resection margins (median survival 24 months; P < 0.001, R0 vs. R1). Loc Adv indicates patients explored, but found to have unresectable tumours owing to local invasion (no metastatic disease) (median survival 16 months; P < 0.19, R1 vs. Loc Adv). Reprinted with permission from Blumgart LH (ed.) Surgery of the liver, biliary tract, and pancreas, 4th edn. Elsevier Saunders, 2006. Despite improvements in preoperative imaging, a considerable number of patients are still found to have unresectable disease at the time of exploration. In a recent report from MSKCC, this number approached 50% of patients with cholangiocarcinoma explored with curative intent.30 In an effort to minimise the number of non-curative laparotomies performed, staging laparoscopy has been utilised. Two recent studies specifically analysing patients with biliary cancer have shown that laparoscopy can identify a large proportion of patients with unresectable disease primarily in the form of radiographically occult metastases, the yield of which is greatest in locally advanced tumours.67,68 Weber et al. evaluated 56 patients with potentially resectable hilar cholangiocarcinomas; 33 were ultimately determined to have unresectable disease, of which 14 (42%) were identified at laparoscopy and spared an unnecessary laparotomy. Additionally, a number of recent reports have suggested a potential role for fluoro-2-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scanning as a means of identifying occult metastatic disease. However, most of these studies include small numbers of patients, and further evaluation is needed before PET can be recommended as a routine screening study for this disease.69–71 In the authors’ experience with FDG-PET for all biliary tract cancer, the information provided influenced management in 24% of patients.72 Technical aspects of intraoperative tumour assessment, exposure and resection are outside the scope of this chapter. The reader is referred to specialty texts for a detailed description of surgical techniques.73 The authors’ general approach involves the use of staging laparoscopy, followed by a full exploration of the abdomen and pelvis, including intraoperative ultrasonography. Resection of the tumour involves, at a minimum, removal of the entire extrahepatic biliary tract from just above the pancreas distally to beyond the biliary confluence with a complete porta hepatis lymphadenectomy. Also, for the reasons cited above, en bloc partial hepatectomy is required in nearly every case in order to achieve complete tumour clearance. Tumour involvement of the main portal vein proximal to its bifurcation additionally requires a vascular resection and reconstruction if technically feasible. Some authors advocate a ‘no-touch’ technique where a hilar en bloc resection is performed that entails resection of the portal vein bifurcation with reconstruction.74 The authors report a 5-year survival advantage of 58% versus 29% (P = 0.02) associated with this approach compared to a conventional hepatectomy. This is clearly an aggressive surgical approach that is likely best applied to a select population. The extent of lymphadenectomy that should be performed remains an area of controversy. Some surgeons advocate an extended nodal dissection as some studies have demonstrated measurable 5-year actuarial survival in the presence of metastatic disease to distant nodal basins (e.g. para-aortic).75,76 However, an analysis of studies specifically reporting 5-year survival in patients would suggest that any nodal involvement is a powerful adverse factor and that very few patients benefit from such an aggressive approach (Table 12.4). Thus, while a complete porta hepatis lymphadenectomy should be routinely performed when attempting complete resection, the authors do not advocate an extended lymph node dissection. As is the case in other tumours, the clinical implication of a negative lymph node on histopathological analysis is likely dependent on the total number of lymph nodes sampled. A study from MSKCC reported that seven lymph nodes appears to be the target sampling number in order to accurately stage hilar cholangiocarcinoma.77 This must be weighed against the reality that, in most series, the median number of nodes sampled from a porta hepatis lymphadenectomy is usually around three. Long-term survival after resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma can be achieved and has improved over recent years.3,4,6,65,78,79 It is clear, however, that the results of resection depend critically on the status of the resection margins. The authors firmly believe that an increase in the use of hepatic resection is responsible for the increase in the percentage of R0 resections (negative histological margins) and the observed improvement in survival after resection. This point is emphasised by a reported series of 269 patients accumulated over a 20-year period demonstrating a progressive increase in the proportion of patients subjected to partial hepatectomy, with a corresponding increase in the incidence of negative histological margins and in survival.80 A more recent study from MSKCC reported results of resection in 106 consecutive patients and showed a median survival of 43 months in patients who underwent an R0 resection compared to 24 months in those with involved resection margins.30 Multivariate analysis showed that an R0 resection, a concomitant hepatic resection, well-differentiated histology and papillary tumour phenotype were independent predictors of long-term survival. The rarity of cholangiocarcinoma has prevented any meaningful clinical trials evaluating the use of adjuvant therapy. Several small, single-centre studies have attempted to investigate the benefit of postoperative adjuvant chemoradiation therapy in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Cameron et al. and Pitt et al. from Johns Hopkins, in two separate reports, provided data suggesting no benefit of adjuvant external beam or intraluminal radiation therapy.81,82 In contrast, Kamada et al. suggested that radiation may improve survival in patients with histologically positive hepatic duct margins.83 Additionally, in a small series of patients, five with hilar cholangiocarcinoma, resectability was reportedly greater in patients given neoadjuvant radiation therapy prior to exploration.84 It must be noted, however, that none of these studies were randomised and most consisted of a small, heterogeneous group of patients. At the present time, there are no data to support the routine use of adjuvant or neoadjuvant radiation therapy, except in the context of a controlled trial. The only phase III trial investigating adjuvant chemotherapy, which used mitomycin/5-fluorouracil (5-FU), included 508 patients with resected bile duct tumours (n = 139), gallbladder cancers (n = 140), pancreatic cancers (n = 173) and ampullary tumours (n = 56).85 On subset analysis, there were no significant differences in overall or disease-free survival for bile duct tumours. As with radiation therapy, there are no data to support the routine use of chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting, until newer agents, such as oxaliplatin, are tested in a randomised controlled fashion.

Malignant lesions of the biliary tract

Introduction

Cholangiocarcinoma

Epidemiology

Natural history

Aetiology

Histopathology

Cholangiocarcinoma involving the proximal bile ducts (hilar cholangiocarcinoma)

Radiological investigation

Preoperative evaluation and assessment of resectability

Stage

Criteria

T1

Tumour involving biliary confluence ± unilateral extension to second-order biliary radicles

T2

Tumour involving biliary confluence ± unilateral extension to second-order biliary radicles

AND ipsilateral portal vein involvement ± ipsilateral hepatic lobar atrophy

T3

Tumour involving biliary confluence + bilateral extension to second-order biliary radicles

OR unilateral extension to second-order biliary radicles with contralateral portal vein involvement

OR unilateral extension to second-order biliary radicles with contralateral hepatic lobar atrophy

OR main or bilateral portal venous involvement

Treatment options

Resection

Results of resection

Adjuvant therapy

Malignant lesions of the biliary tract