pulmonary edema (acute diastolic dysfunction), acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina, acute aortic dissection, active bleeding, or central nervous system (CNS) catastrophe (hypertensive encephalopathy, intracerebral or subarachnoid hemorrhage, or severe head trauma). In each case, adequate control of the blood pressure is the cornerstone of successful therapy.

TABLE 44.1 The Clinical Syndromes of Severe Hypertension | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

in patients with renal allografts. In each of these conditions, a sudden increase in blood pressure may cause acute pulmonary edema, hypertensive encephalopathy, cerebrovascular accident, and death.

one of any number of different etiologies.10 Moreover, in the individual patient with malignant hypertension, on clinical grounds it is often difficult to distinguish whether the underlying hypertension is primary or secondary.

TABLE 44.2 Etiologies of Malignant Hypertension | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

incidence rate did not change over the 24-year period from 1970 to 1993. Recent studies have examined the changing demography of patients with malignant hypertension over the last 40 years.25,26 The incidence rate for malignant hypertension has remained relatively stable over time. In one study from the United Kingdom, 446 patients with malignant hypertension were included.25 Mean age was 48 ± 12 years, 65.5% were male gender, 64.7% white European, 20.4% African-Caribbean, and 14.8% South Asian. No significant demographic differences at diagnosis were evident over the 40 years, with the exception of a significant increase in the proportion of malignant hypertension among ethnic minorities (South Asian and Afro-Caribbeans).

TABLE 44.3 Retinal Changes in Hypertension | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

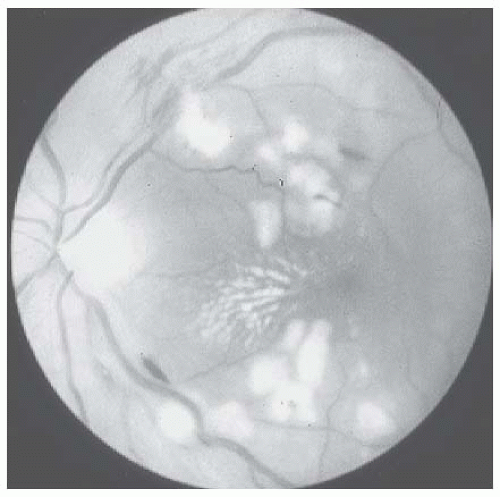

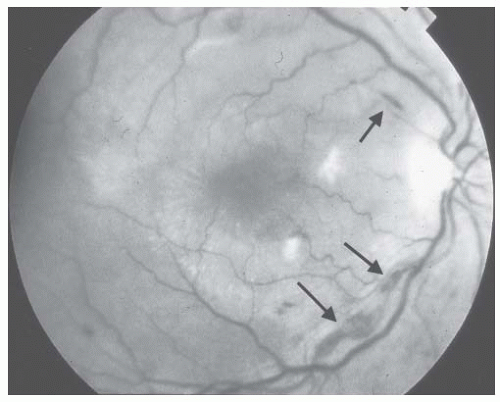

periphery of the fundus. They are caused by venous or arterial occlusion.43 Hard exudates may appear as multiple small white dots that give a powdery appearance to the retina, or they may appear as large glistening spots that are sharply defined from the adjacent retina. Arteriosclerotic retinopathy can also cause localized areas of retinal edema and hemorrhage due to occlusion of small branch veins. However, the principal findings of hypertensive neuroretinopathy, namely, striate hemorrhages, cotton-wool spots, and papilledema, are absent (Table 44.3). The finding of retinal arteriosclerosis in hypertensive patients usually does not imply a poor prognosis.

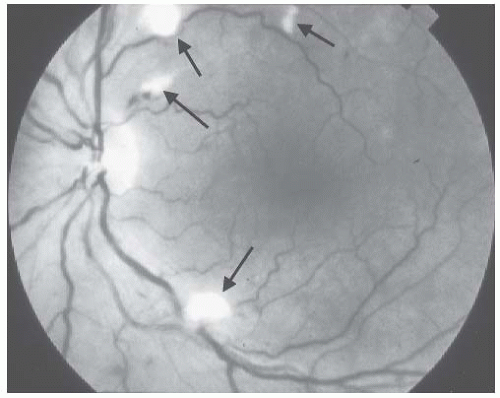

FIGURE 44.1 Striate hemorrhages (arrows) in the fundus of a 48-year-old white woman with secondary malignant hypertension due to underlying immunoglobulin A nephropathy. |

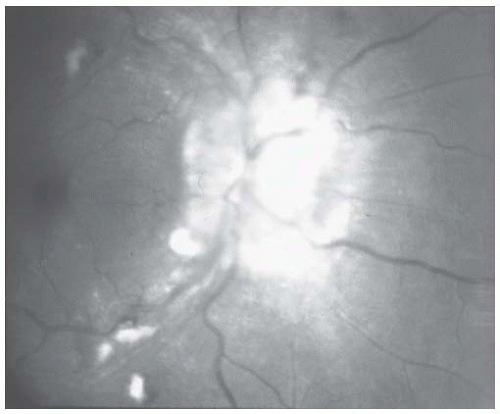

hypertension, papilledema is usually accompanied by striate hemorrhages and cotton-wool spots (Figs. 44.3 and 44.4). When papilledema occurs alone, the possibility of a primary intracranial process such as a tumor or cerebrovascular accident should be considered.

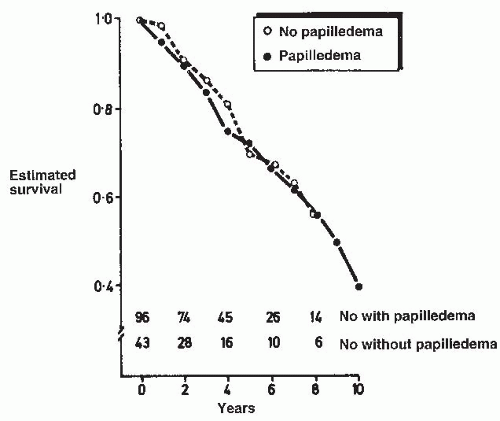

but no papilledema.49,50,51,52 This lack of a difference in prognosis for patients with hypertensive neuroretinopathy whether or not it is accompanied by papilledema may be explained by the fact that cotton-wool spots and papilledema share a similar pathogenesis (see later discussion).53,54

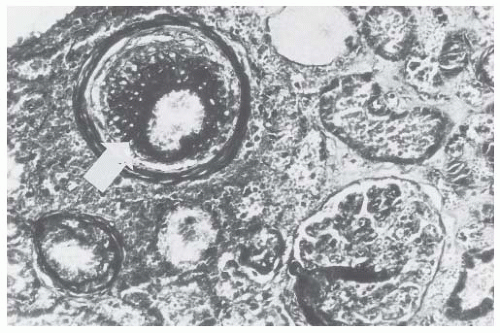

and proliferative endarteritis. The glomeruli were normal except for ischemic changes. Multifocal tubular necrosis was present and presumed to be secondary to ischemia. In most of these patients, the diagnosis of malignant hypertension was delayed because the patients were initially considered to have rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis or systemic vasculitis, which was treated with high-dose steroids. The diagnosis of malignant hypertension was not suspected until autopsy revealed malignant nephrosclerosis.

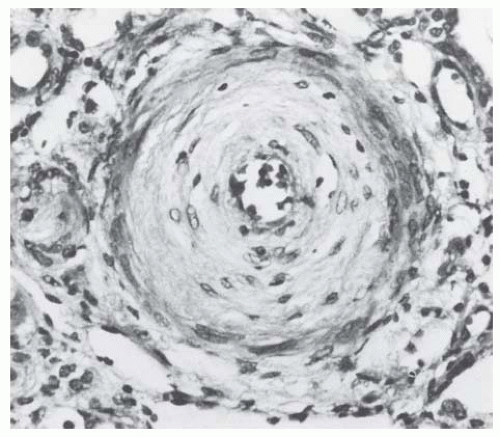

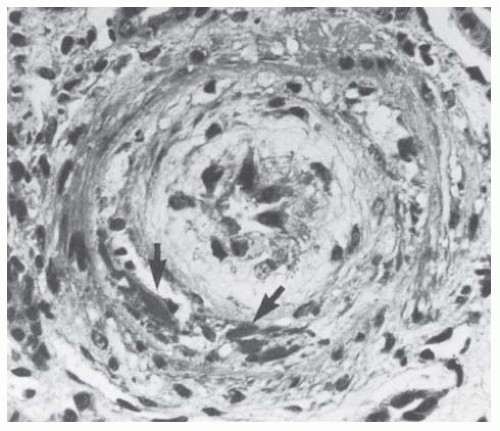

FIGURE 44.7 Fibrinoid necrosis in a large arteriole (arrow). Intimal onionskin formation is also present. (Trichrome stain.) (Photograph courtesy of Steve Guggenheim, MD.) |

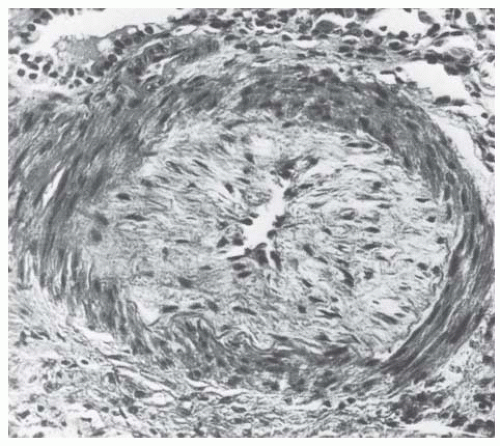

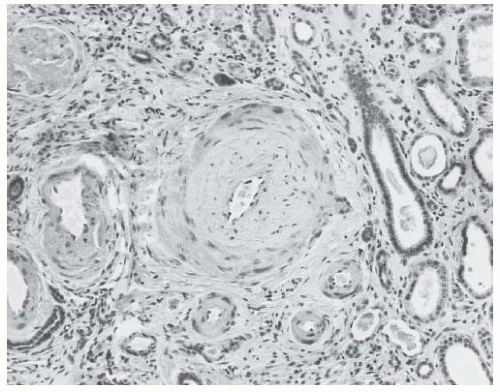

amorphous material (Fig. 44.9). In fibrous intimal thickening, there are hyaline deposits, reduplicated bands of elastica, and coarse layers of pale connective tissue with the staining properties of collagen (Fig. 44.10). In rare cases, fibrinoid necrosis may also be apparent in the interlobular arteries.68

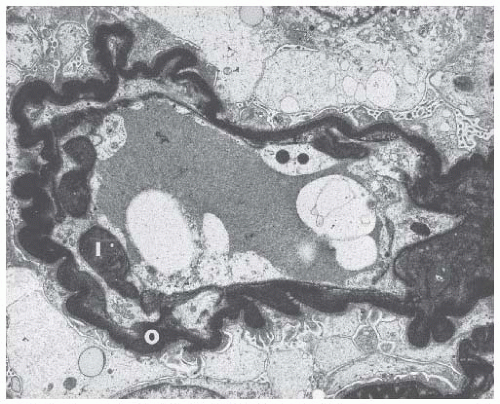

obsolescence observed in benign hypertension. In addition to the wrinkled basement membrane observed in benign nephrosclerosis, there is constriction of the glomerular vascular bed in malignant nephrosclerosis due to the deposition of a new subendothelial layer of basement membrane material inside the original basement membrane (Fig. 44.15).73 The new capillary lumen formed by this process is smaller, resulting in decreased blood volume in the ischemic glomerulus.

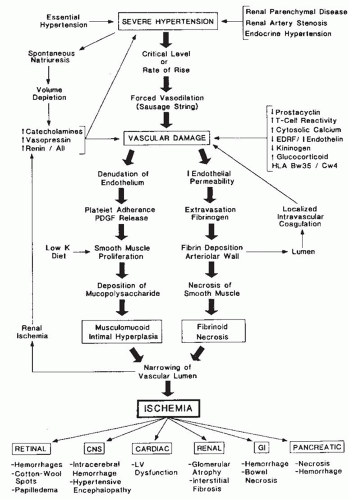

by severe hypertension.81 Undoubtedly, a marked increase in blood pressure is pivotal. Severe hypertension is the common element in malignant hypertension in humans and in each of the animal models of malignant hypertension. Moreover, reduction of the blood pressure leads to a resolution of the malignant phase regardless of the underlying etiology. Thus, a significant elevation of the blood pressure is necessary for the development and progression of malignant hypertension. The major issue is whether the mechanical stress of severe hypertension alone is sufficient to cause the transition from benign to malignant hypertension. Because there is considerable overlap in the levels of blood pressure seen in patients with benign and those with malignant hypertension, it is likely that severe hypertension alone is not sufficient to cause the malignant hypertension in all patients and that additional factor(s) probably participate. The vasculotoxic theory proposes that humoral factors interact with the hypertension-induced hemodynamic stress to cause the vascular damage observed in malignant hypertension.

FIGURE 44.16 Pathophysiology of malignant hypertension. AII, angiotensin II; EDRF, endothelium-derived relaxing factor; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; LV, left ventricular. |

parenteral antihypertensive agents is recommended for the initial management of malignant hypertension. In general, parenteral therapy should be utilized in patients who have evidence of acute end-organ damage or who are unable to tolerate oral medications.

TABLE 44.4 Indications for Parenteral Therapy in Malignant Hypertension | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

end-diastolic volume, pulmonary congestion improves because of the reduction in pulmonary capillary pressure. Thus, even in patients with malignant hypertension complicated by pulmonary edema, afterload reduction rather than vigorous diuretic therapy should be the mainstay of initial therapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree