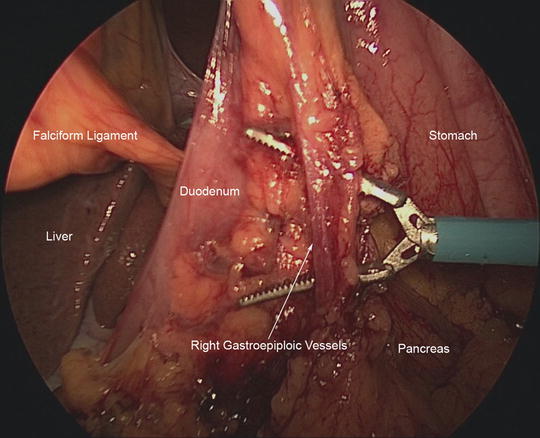

Fig. 7.1

This figure demonstrates the major arteries that must be identified during laparoscopic distal gastrectomy as well as the lymph node stations according to the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma

The stomach has an extensive network of lymphatic channels, which is the most common site of extra-gastric disease spread. According to the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma [11], there are 33 lymphatic stations providing drainage of the stomach (Fig. 7.1). The extent of lymphadenectomy or lack thereof (i.e., D0, D1, or D2) is defined by the nodal stations removed. A D0 lymphadenectomy involves “shelling out” the stomach without removal of the adjacent lymphatic tissues. D1 lymphadenectomy involves harvesting all of the perigastric lymph node stations along the lesser and greater curvatures of the stomach. Specifically, these are the pericardial nodes (station 1), nodes along the lesser curvature (station 3), nodes along the short gastric and gastroepiploic vessels (stations 4a and 4b), the nodes along the pyloric channel (stations 5 and 6), and nodes at the left gastric artery (station 7). The D2 nodal stations include the D1 stations as well as the lymphatic tissues along the proximal common hepatic artery (station 8), the celiac trunk (station 9), the splenic artery (station 11), and hepatoduodenal ligament (station 12). Knowledge of these lymphatic stations is important for oncologically sound gastrectomy. In our practice, we routinely perform what is termed a D1 + β dissection for distal gastric cancers. This is a modification of the classic D2 lymphadenectomy that omits splenectomy and dissection of lymphatic tissues along the distal splenic artery or splenic hilum.

Preoperative Considerations

After the diagnosis of gastric cancer has been obtained, several steps are necessary prior to surgery. This includes a staging workup consisting of endoscopic ultrasound and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis to evaluate the extent of disease and to rule out distant metastasis. Once early gastric cancer has been confirmed, cardiac clearance is obtained as indicated in the elderly and in patients with serious comorbidities. Other laboratory tests are performed as indicated based on each individual patient’s needs. Once the preoperative evaluation has been completed, the patient is ready for surgery. We maintain the patient on nil per os after midnight on the evening prior to surgery with the daytime diet limited to clear liquids. No other bowel prep is administered.

Surgical Technique

Patient Positioning and Setup

After transport to the operating room, the patient is placed in the supine position on the operating table. We do not use lithotomy position for gastrectomy. Prior to induction of general endotracheal anesthesia, sequential compression devices are placed on the bilateral lower extremities and intravenous antibiotics are administered. After endotracheal intubation, a Foley catheter and orogastric tubes are placed. We do not place central venous catheters, although radial artery catheters are often placed to facilitate accurate hemodynamic monitoring. Once these initial steps have been completed, both arms are tucked and the abdomen is prepped and covered with an Ioban drape.

The attending surgeon with the assistance of the surgical oncology fellow typically performs the procedure. The operating surgeon stands on the patient’s left side and the assistant and scrub technician stand on the right. Video monitors are placed above either side of the patient’s head at the operating surgeon’s eye level providing equal visualization to both the operating surgeon and the assistant (Fig. 7.2). Finally, the patient is placed at 30-degree reverse Trendelenburg position, which allows gravity to retract organs to better visualize key structures.

Fig. 7.2

Patient positioning and operating room setup

Instruments

When performing laparoscopic distal gastrectomy, appropriate minimally invasive equipment is mandatory. Small and medium-sized Weck™ (Teleflex Inc., Research Triangle Park, NC) clips are used for ligation of relatively large blood vessels encountered during gastrectomy. Much of the dissection, however, can be performed with energy sealant devices. We frequently use an energy dissector that also features monopolar electrocautery. A laparoscopic liver retractor is routinely used to retract the left lateral segment of the liver, and laparoscopic linear stapling devices are used for division of the duodenum and stomach and for creation of the gastrojejunal anastomosis. We use the Endostitch™ (Covidien Inc. Mansfield, MA) device to close the common channel of the gastrojejunostomy. Finally, a sterile extraction bag is introduced through a 12-mm port and used to remove the specimen from the peritoneal cavity.

Trocar Placement

Five trocars are used to perform the laparoscopic distal gastrectomy. They are placed in a semi-elliptical pattern with the base of the ellipse at the umbilicus (Fig. 7.3). We employ three 10/12-mm trocars and two 5-mm trocars. The first trocar is a 10/12-mm trocar in the midline just below the umbilicus that is placed via the Hasson technique. Occasionally, the peritoneal cavity is first accessed with a Veress needle at Palmer’s point in the left upper quadrant. After the first trocar is placed, the abdomen is insufflated to 15 mmHg and the remaining bladed trocars are placed under direct visualization. The two 5-mm trocars are placed a hand’s breadth apart to the right of the midline. One 5-mm trocar is placed directly to the right of the peri-umbilical trocar and the second 5-mm trocar is placed in the lateral aspect of the right upper quadrant. The remaining two 10/12-mm trocars are placed to the left of the umbilicus mirroring the positions of the trocars on the right side of the abdomen.

Fig. 7.3

Trocar placement using three 10/12-mm trocars and two 5-mm trocars

Diagnostic Laparoscopy

Once the initial trocar is placed at the umbilicus, the abdomen is explored with a 10-mm, 30-degree angled laparoscope to confirm the absence of metastatic disease. Some centers routinely obtain peritoneal washings for cytologic examination. Although these washings may be performed [4], we have observed an extremely low number of locoregional or peritoneal recurrences in our institutional experience that does not justify the routine performance of peritoneal washings. On initial inspection of the abdomen, the peritoneal surfaces are carefully examined. This allows the surgeon to rule out peritoneal seeding and carcinomatosis. The hemidiaphragms, liver, and pelvis are also inspected since these locations are common sites for metastasis to occur.

Initial Mobilization of the Stomach and Division of the Duodenum

Mobilization of the stomach begins by dividing the gastrocolic ligament. The omentum is retracted cephalad and upward toward the anterior abdominal wall. The avascular embryonic fusion plane between the omentum and transverse colon is identified and divided to enter the lesser sac. Once the proper plane is identified, the omentum is completely mobilized off of the transverse colon from right to left. Depending on the patient’s body habitus and the amount of intra-abdominal fat, this first step can be particularly difficult, but it is critical for an oncologically sound operation. Of note, we use the Ligasure™ (Covidien Inc. Mansfield, MA) device for this step, but other energy devices may be used.

The stomach is then lifted upward and posterior attachments between the stomach and pancreas are divided. We do not routinely dissect the anterior leaflet of the transverse mesocolon nor do we resect the capsule of the pancreas (i.e., omental bursectomy). After disease in the lesser sac has been excluded, we then perform intraoperative esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). This procedure, by the primary surgeon or assistant, is always performed to confirm the location of the tumor and to mark the point of transection of the stomach. An atraumatic bowel clamp is used to occlude the proximal jejunum near the ligament of Treitz and the endoscope is passed into the stomach. Once the tumor is identified endoscopically, the serosal surface of the stomach is marked with cautery 5 cm proximal to the tumor to allow adequate margins.

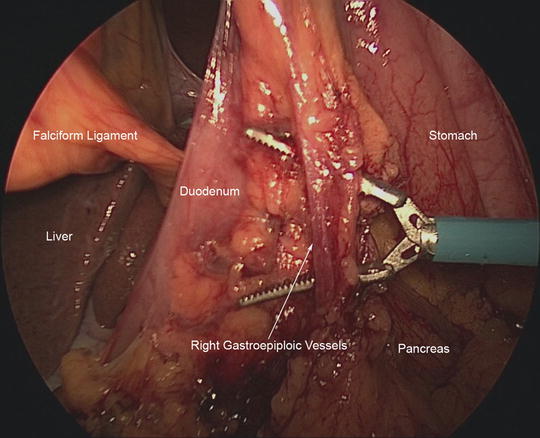

After EGD has been completed, mobilization of the stomach continues. The omentum along the greater curvature of the stomach is mobilized up to the level of the proposed line of transection. Then, our attention is turned to fully mobilizing the distal stomach. The right gastroepiploic artery and vein (Fig. 7.4) terminate near the distal greater curvature of the stomach at the inferior border of the pancreatic neck. This vascular bundle is dissected close to the substance of the pancreas and the lymphatic tissues are swept toward the specimen. The right gastroepiploic vessels are ligated using Weck clips. The division of these vessels leads to a plane for subsequent transection of the duodenum. The duodenum is carefully encircled by creating a plane posterior to the duodenum and opening the hepatoduodenal ligament. We use the vein of Mayo as the landmark to ensure that we are distal to the pylorus. We transect the duodenum using a linear stapler with a tan cartridge.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree