Fig. 12.1

Supine OR positioning depicting patient secured to bed, shoulder rolls in place, in the lithotomy position, buttock off end of the bed, with thighs as parallel as possible to the abdomen

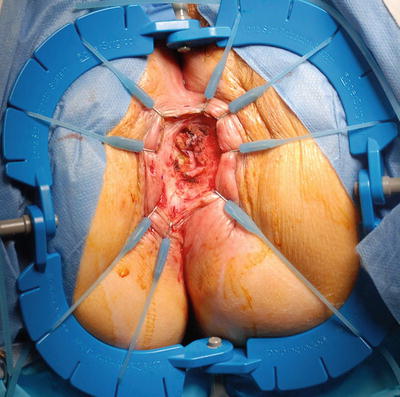

Fig. 12.2

Anus sewn closed at initiation of case

Port Placement and Entry into the Abdomen

Entry into the peritoneal cavity can be accomplished using the Hasson or Veress technique in the infraumbilical position. If the patient is obese or has had previous surgery at the umbilicus (prior laparotomy, umbilical hernia repair), a safer alternative is to use the Veress or Visiport technique in the left upper quadrant. Pneumoperitoneum is established to 15 mmHg, and additional 5-mm ports are placed under direct vision in the following locations: suprapubic, right lower quadrant, and left mid-abdomen (future colostomy site) (Fig. 12.3). An additional trocar may be placed in the epigastrium if needed, taking care not to place it too far to allow laparoscopic instruments to reach the deep pelvis. The laparoscopic abdominal portion has also been described using single-port access, with a single-port device (SILS Port, Covidien, Inc., Norwalk, CT, or the GelPOINT Advanced Access Platform, Applied Medical, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA) [18], and positioned at the colostomy site, umbilicus, or Pfannenstiel location. Since the specimen can eventually be removed via the perineal incision, the laparoscopic APR procedure does not need any extension of abdominal incisions for specimen extraction, as required for laparoscopic colectomy procedures. This is another reason why we do not typically utilize the hand port routinely, although some surgeons find the insertion of the hand helpful for pelvic retraction (Fig. 12.4). A 5-mm or 10-mm 30-degree scope is used. The Olympus EndoEYE camera (Olympus, Central Valley, PA) may help facilitate visualization in the pelvis, particularly with the single-port laparoscopic approach. Once the ports are placed, both the surgeon and assistant may stand on one side of the patient, but we prefer to have the surgeon stand on the patient’s right side and assistant on the left. Monitors are positioned to the patient’s left and right at the foot of the bed. An additional monitor may be placed above the patient’s left shoulder to facilitate splenic flexure mobilization, when needed.

Fig. 12.3

OR setup with trocar, surgeon, and monitor positioning

Fig. 12.4

Laparoscopic APR through a hand port. JP sewn to specimen to pull through the perineal wound and leave the JP in the pelvis to drain

Colon Mobilization and Division of the Superior Hemorrhoidal Vessels

The liver and peritoneal surfaces are visually inspected for evidence of metastases. The patient is placed in steep Trendelenburg position with the right side down. The small bowel is swept out of the pelvis using 2 atraumatic graspers. The descending colon and sigmoid colon are mobilized from the sigmoid fossa along the white line of Toldt in a lateral-to-medial fashion, using Endo Shears (Covidien, Inc., Norwalk, CT) with cautery. An alternative approach is the medial dissection where the sigmoid is lifted, the peritoneum incised, and the plane between the mesorectal fascia and the retroperitoneum is created, taking particular care to leave the ureter in the retroperitoneum and sweep it down from the specimen. In most cases, the splenic flexure and proximal descending colon do not need to be mobilized in order to have sufficient length for the end colostomy. The sigmoid colon is grasped and retracted upward, and the superior hemorrhoidal vessels are identified within the mesentery. Using the Endo Shears and atraumatic grasper, windows in the mesentery are created around the superior hemorrhoidal vessels. After demonstrating once more that the ureters are out of the line of transection, the vessels are ligated at their origin. This maneuver can be performed with a 5- or 10-mm (depending on the amount of tissue to be divided) advanced bipolar device or laparoscopic stapler with white 2.5-mm staple cartridge (Fig. 12.5a, b). A grasper should be positioned and ready to obtain prompt control of the vascular stump, in the event of inadequate hemostasis.

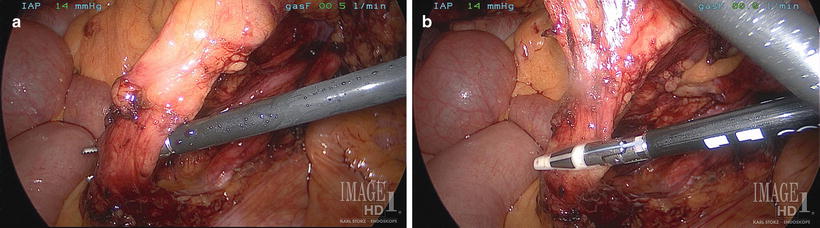

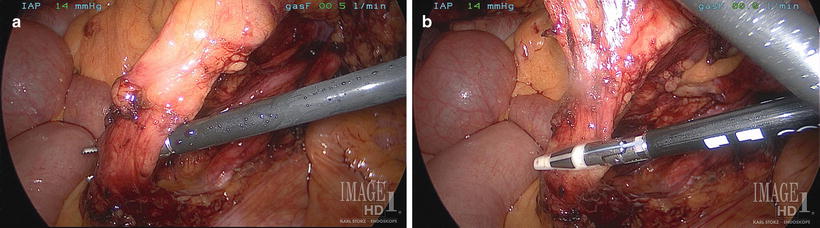

Fig. 12.5

Intracorporeal exposure (a) and ligation (b) of the inferior mesenteric/superior hemorrhoidal vessels

Total Mesorectal Excision

The presacral plane is further developed into the wispy areolar tissue, using either Endo Shears or the L-hook cautery. Alternative instruments such as ultrasonic energy devices (Harmonic Scalpel™, Ethicon, Cincinnati, OH) or articulating laparoscopic instruments (Cambridge Endo, Framingham, MA) may facilitate the exposure and dissection. The hypogastric nerves are visualized medially along the sacrum as well as laterally along the pelvic sidewall and are left intact (Fig. 12.6). The total mesorectal dissection proceeds into the pelvis to the pelvic floor (levators), first posteriorly and then laterally, and lastly the anterior plane is approached. The colon and rectum can be retracted out of the pelvis with the assistance of gravity, a laparoscopic grasper, or suture secured to the abdominal wall or trocar. In women, the uterus and adnexa can be suspended with a suture passed through the abdominal wall or by a uterine manipulator placed at the initiation of surgery. During the dissection it is imperative to identify and preserve both ureters, the pelvic sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves, iliac blood vessels, presacral veins, vagina, seminal vesicles, and prostate. Of course, tumor involvement of any of these structures mandates en bloc resection. The posterior dissection will take you to and through Waldeyer’s fascia and the anterior curve of the pelvis to the muscular pelvic floor. At this level, it is particularly important not to “cone in” on the specimen, taking care to leave a waist of muscle and adipose tissue covering the thinned rectum as it dives into the pelvic floor musculature (corresponding with the location of the majority of these low rectal tumors). The anterior plane is the most challenging, particularly below the anterior peritoneal reflection (see Fig. 10.8). Developing the posterior and lateral planes first allows for improved visualization of the proper anterior plane of dissection. The use of multiple graspers to create tissue tension helps find the correct plane. Rigid sizers placed in the vagina may help better retract and define the rectovaginal septum dissection in women. The laparoscopic suction irrigator is useful to remove smoke and fluid and as a deep pelvic retractor. Alternatively, there are cautery instruments with side ports for smoke evacuation controlled by the surgeon with trumpet valves.

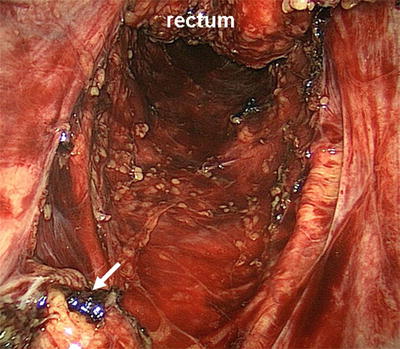

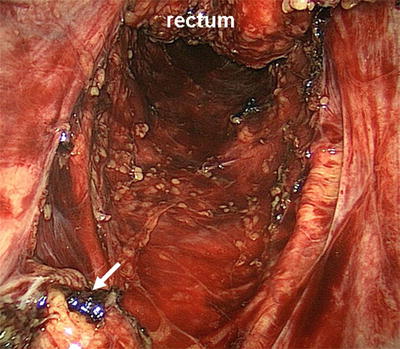

Fig. 12.6

Dissection in the presacral plane. The white arrow indicates the superior hemorrhoidal artery (ligated) in a patient with Crohn’s proctitis. Hypogastric nerves are visible laterally

Dissection anteriorly begins with opening of the peritoneal reflection in a horseshoe (i.e., upside down U) fashion. Maintaining cephalad retraction on the distal sigmoid and upper rectum allows the plane to be more easily delineated. This anterior reflection of the peritoneum is variable, though, in general, the lower one-third of the rectum is without a peritoneal covering. Just deep to this are the seminal vesicles in men, characterized by their white tubular appearance. Dissection continues caudally along the endopelvic fascia, also referred to as Denonvilliers fascia, with identification of the smooth posterior border of the prostate gland. The periprostatic plexus is located along this anterior dissection (see Fig. 10.8). This plexus contains both sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers that innervate the prostate, prostatic and membranous urethra, seminal vesicles, ejaculatory ducts, and bulbourethral glands. The neurovascular bundles are normally located anterolaterally along the pelvic sidewall prior to joining the plexus. Damage to these nerves can result in incomplete erection, lack of ejaculation, retrograde ejaculation, or complete impotence.

Controversy and differing opinions exist regarding the proper plane of dissection anteriorly, as well as the exact location of Denonvilliers fascia. Many surgeons feel that Denonvilliers fascia is more adherent to the prostate than the rectum. Therefore, dissection immediately on the fascia propria of the rectum in the plane of the TME will allow for complete removal of an intact anterior mesorectum while leaving Denonvilliers fascia on the prostate and avoiding damage to the nerves. Others suggest that Denonvilliers fascia is more closely adherent to the rectum, without a plane posterior to it. In this case, the fascia will be removed along with the rectum during a standard TME dissection. In either light, most colorectal surgeons are aware of the loose areolar tissue immediately outside the fascia propria, providing familiar territory for initial dissection. The choice distally then remains whether to perform dissection on the rectal side or prostatic side of Denonvilliers fascia and to understand the potential consequences of each. Likely the optimal approach is to dissect on the prostate and seminal vesicles for large anterior tumors to minimize the risk of a positive anterior margin. This comes with the obvious increased risk of nerve damage. In women, a similar dissection should occur along the posterior vaginal wall.

Division of the Sigmoid Colon and Ostomy Creation

The sigmoid colon is grasped and retracted toward the anterior abdominal wall, and a window is created in the mesentery that is sufficiently large to accommodate the 45-mm or 60-mm blue-load laparoscopic stapler. Two firings may be necessary to fully divide the colon. The remaining mesentery between the colon and the superior hemorrhoidal vessels is divided with the energy sealing device (Video 12.2). The proximal end is grasped with a ratcheted grasper. A 19-French round Jackson-Pratt drain is placed into the pelvis using the right lower quadrant port site and can be sutured to the specimen to assure it is pulled down into the pelvis during specimen extraction through the perineal wound. The end is brought through the abdominal wall at the right-sided port and secured to the skin with a nylon suture. Insufflation is maintained. The skin site for the ostomy is created centered at the left lower quadrant 5-mm port. A ring of skin and subcutaneous tissue is cored out using electrocautery. Army-Navy retractors are used for exposure. The anterior fascia is incised with a cruciate incision, the rectus is splayed using a large Kelly clamp, and the abdomen is entered by dividing the posterior sheath and peritoneum in a cruciate fashion using electrocautery. The proximal colon end is brought through the abdominal wall. The 12-mm umbilical port site is closed with a Vicryl suture through the fascia, and skin is closed on all ports with 4–0 Monocryl and either Dermabond or Mastisol and Steri-Strips. The staple line is excised from the end of the colon, and the colostomy is matured with 3–0 Vicryl sutures in a Brooke fashion. The stoma appliance is applied. Having completed the abdominal portion of the dissection, the team prepares for the perineal dissection.

Perineal Dissection

The patient is placed onto a second operating room table in the prone jackknife position (Fig. 12.7) over soft chest and hip rolls. Bony prominences are padded and the buttocks are taped apart using heavy cloth tape. Attention is focused on the colostomy, which should not have any direct pressure on it if positioned off the hip roll. The field is prepped with Betadine. The anus has already been sewn closed. After confirming the location of the coccyx posteriorly, the ischial tuberosities laterally, and the mid-perineum anteriorly, an elliptical incision is made circumferentially around the anus. The Lone Star Retractor™ (CooperSurgical, Trumbull, CT) is secured. The extrasphincteric plane is entered and followed to the levators (Fig. 12.8). The coccyx is palpated, and the anococcygeal ligament is divided posteriorly to enter the pelvis. The surgeon’s finger is placed in this space and hooked around the levator muscles. A cylindrical dissection is performed, taking a circumferential portion of levator muscle with the specimen to avoid narrowing it and creating a “waist” [19, 20]. The specimen is exteriorized through the posterior space, and the more difficult anterior plane is better visualized and dissected. In men, the dissection proceeds just posterior to the prostate and urethra. In women, the plane is developed between rectum and vagina. The surgeon’s finger can be placed in the vagina to help feel and expose this plane. Tumor involvement of the prostate or vagina mandates en bloc resection. In the case of a bulky tumor that cannot be exteriorized (or a narrow pelvis), the specimen is circumferentially dissected, disconnected, and pulled out through the pelvis. The surgeon may choose to open and examine the specimen on the back table or, ideally, in coordination with the pathologist to more accurately determine margin status.

Fig. 12.7

Patient positioning in the prone jackknife position. Chest and hip rolls in place and buttocks taped widely apart

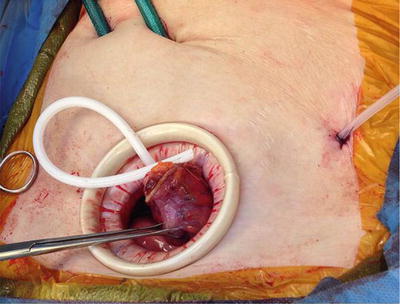

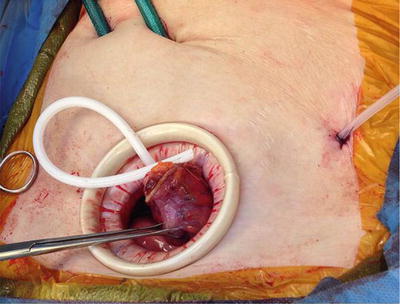

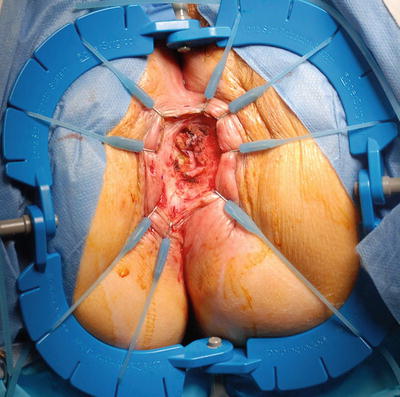

Fig. 12.8

Starting the perineal dissection, the Lone Star Retractor has been set up and extrasphincteric plane is being developed

The tip of the Blake drain is positioned deep in the pelvis. The perineal wound is thoroughly irrigated and hemostasis is ensured. The peritoneum is not closed primarily, as this creates a closed space in the pelvis, allowing for accumulation of blood and fluid that is at risk for becoming infected and contributing to perineal wound complications and pelvic abscess [21]. The wound is closed in layers, first using one to two layers of 0 Vicryl figure-of-eight interrupted sutures, and then one to two layers of 2–0 Vicryl figure-of-eight interrupted sutures, irrigating with saline between each layer. The skin is reapproximated with loosely spaced 2–0 Vicryl simple interrupted sutures. Local anesthetic (0.25 % marcaine with epinephrine) may be infiltrated. A dry sterile dressing is applied.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree