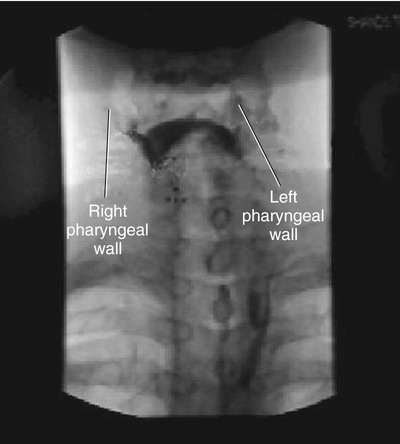

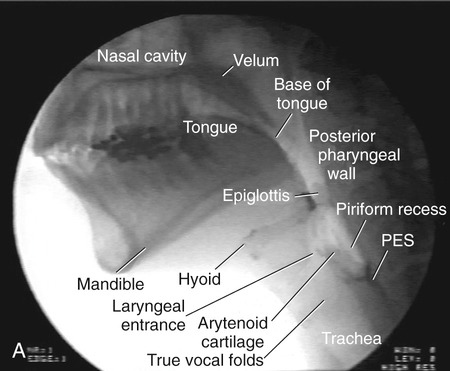

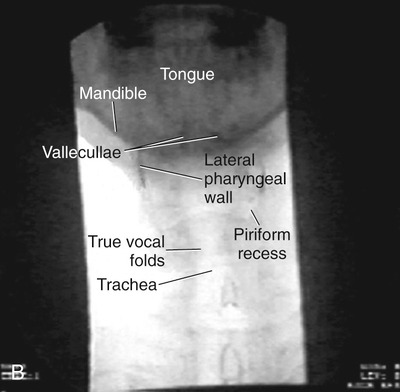

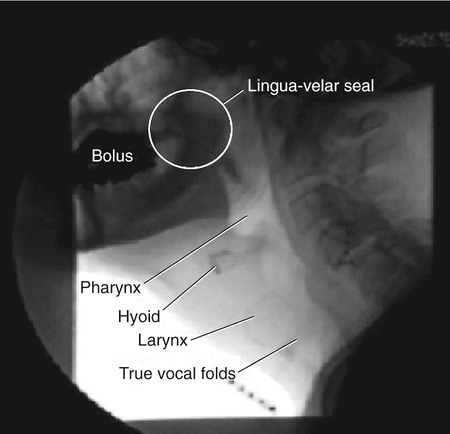

1. Explain why it is important to “image” the swallowing mechanism and evaluate swallow function with an instrumental study. List some basic guidelines to help determine whether any instrumental swallowing examination is indicated. 2. Describe the basic components and potential modifications of a fluoroscopic swallowing examination and an endoscopic swallowing examination. 3. Describe some of the strengths and weaknesses of the fluoroscopic swallowing examination and the endoscopic swallowing examination. 4. Compare the endoscopic examination with the fluoroscopic examination, specifically regarding the identification of various dysphagia characteristics. Many instrumental procedures may be used to evaluate different aspects of swallowing function. This chapter addresses the two most commonly used procedures: videofluoroscopy (also called videofluorography) and flexible endoscopy (also known as fiberoptic endoscopy or transnasal endoscopy). Procedures related to these primary methods are introduced and other instrumental techniques for swallowing evaluation are briefly mentioned. However, before these instrumental evaluation procedures are detailed, they should be placed in the context of the overall clinical evaluation of the adult patient with dysphagia. Frequent questions about these procedures include “What are they intended to achieve?” and “When is an instrumental procedure indicated?” The following information is derived largely from practice guidelines published by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.1–3 The concept underlying the use of practice guidelines is that they result from the creative, clinical, and scientific input of many experienced professionals with thorough professional review. In that regard, although these views may change with the acquisition of new information at a given point in time, they represent a fair summary of existing knowledge and opinion. Instrumental examinations of swallowing are only a part of the comprehensive examination of swallowing performance and function. In general, a thorough clinical examination (see Chapter 9) should precede any instrumental examination. The clinical examination can be important in tailoring specific questions to be addressed in an instrumental examination and provides a comprehensive clinical profile of patients in whom dysphagia is suspected. Thus instrumental examinations of swallowing may accomplish any number of objectives depending on the patient and the clinical situation. These examinations (1) provide valuable information on the anatomy and physiology of structures and muscles used in swallowing, (2) evaluate the ability of a patient to swallow various materials, (3) assess secretions and the patient’s reaction to them, (4) document the adequacy of airway protection and the coordination between respiration and swallowing, and (5) help evaluate the impact of compensatory therapy maneuvers on swallowing function and airway protection. Although the fluoroscopic and endoscopic examinations of swallowing function are not mirror images, they do share many common functions. In addition, each imaging study has specific attributes that the other may not possess. Furthermore, because each examination provides a permanent video record of the swallowing evaluation, both contribute to increased objectivity with enhanced documentation and the ability to review results of the respective studies. Box 10-1 summarizes various purposes attributed to instrumental swallowing examinations. Perhaps the most overt purpose of any instrumental swallowing examination is the ability to image the structures of the swallowing mechanism and the movement of those structures during swallowing and other movements that may help assess their functional integrity. This assessment involves the lips, tongue, jaw, velopharyngeal mechanism, pharynx, larynx, and esophagus. Evaluation of these structures should incorporate some indication of anatomic adequacy and movement capability. In some cases it is possible to assess or perhaps infer sensory integrity and motor functions. Beyond basic anatomy and movement of specific structures, coordinated movement among various components of the swallow mechanism should be assessed with reference to swallowing function. This assessment requires the patient to swallow materials of varying sizes and textures to allow inspection of adjustments (either positive or negative) within the swallowing mechanism. This component of the instrumental examination can help identify misdirection (specifically entrance into the airway) of a bolus and post-swallow residue as a result of inefficient swallowing. If aspiration is identified, the instrumental examination is helpful in differentiating situations when the patient is more likely to aspirate versus those when aspiration is less likely. By using a variety of swallowed materials and incorporating compensatory maneuvers, clinicians may make inferences regarding the safest and most efficient material to swallow and the need for any postural or other adjustments that improve swallowing safety and/or efficiency. Secretions pooled within the swallowing mechanism can be problematic for patients and contribute to respiratory complications. These fluids should be identified and described, including the patient’s reaction to them and the patient’s ability to remove them from the swallowing tract. In some situations the clinician may conclude that oral feeding is not safe or adequate and hence might use the results of instrumental examinations to recommend nonoral feeding sources (or to recommend discontinuation of nonoral feeding sources with reestablishment of oral feeding). In short, instrumental examinations of swallowing function provide objective imaging of the swallowing mechanism that assists dysphagia clinicians in determining the need for and the direction of swallowing rehabilitation. More details of the fluoroscopic and endoscopic swallowing examinations are provided in later sections. Various authors and health care institutions use different terms for what is essentially the same examination. Box 10-3 lists several name variants for this procedure. This list is not comprehensive but is probably representative of the variation that exists in nomenclature. The term modified barium swallow, initially coined by Logemann,4 can be interpreted literally. The traditional barium swallow is focused on the esophagus and stomach and uses large amounts of liquid barium (contrast agent) and still-frame pictures to image the expanded esophagus and evaluate gastric emptying or other upper gastrointestinal functions. This examination is usually done with the patient in one or more combinations of lying positions. The adult patient with dysphagia is likely to be compromised both by the large amounts of liquid barium and by the lying position during swallowing attempts. Therefore this examination was modified to use smaller amounts of contrast material varying in size and consistency and to examine the patient in an upright position (whenever physically possible) to resemble the position most typically associated with eating. This procedure has become known as the modified barium swallow (MBS). Some health care professionals and researchers held to different conventions in selecting a name for this relatively new procedure. Gastrointestinal (GI) radiologists often referred to the procedure as an upper GI series with hypopharynx. This term reflects the traditional esophagram view but with the addition of a study of the hypopharynx. Other terms in the literature include videofluorographic swallow study (VFSS),5,6 videofluorographic barium examination (VFBE),7 and videofluorographic swallow examination (VFSE).8 Presumably, each of these terms was intended to identify the unique radiographic procedure that evaluates oropharyngeal swallowing function. Clinicians in different areas may know or use other terms that refer to the same study. This chapter uses the more generic name variant, videofluoroscopic swallowing examination. The videofluoroscopic swallowing examination can have multiple objectives. The primary objective is to obtain a video image of the upper aerodigestive tract during the act of swallowing. By manipulating what is swallowed, how it is swallowed, and patient positioning, clinicians can complete a comprehensive assessment of swallowing ability. Box 10-4 lists the more overt objectives of a videofluoroscopic swallowing examination. Additional objectives may be appropriate for individual patients and/or problems.9 Evaluation of the swallowing mechanism is initially approached by identification and description of any deviations in the anatomy of structures within the swallowing tract. This presupposes the clinician’s detailed knowledge of anatomy, including radiographic anatomy. Figure 10-1 depicts both lateral and anterior radiographic views of a normal swallowing mechanism. Review of anatomic detail and examples of normal swallow physiology may be found in narrated Video 2-3 on the Evolve site that accompanies this textbook. Basic physiology of the swallowing mechanism may be evaluated by asking the patient to phonate, breath hold, perform a Valsalva maneuver, produce falsetto phonation, or perform other activities that facilitate movement of the structures within the swallowing tract. This component of the evaluation is helpful in identification of potential movement deficits that may contribute to oropharyngeal dysphagia and in selecting appropriate compensatory maneuvers. A standard protocol is highly recommended for the fluoroscopic study.5,6,9 Standardizing the protocol increases consistency and reproducibility of examinations both within and across patients. The use of a standard protocol does not preclude individual variations that may be required for specific patients or problems; however, it does provide a consistent framework from which reasonable variations may be accomplished. Several factors within the protocol must be considered, including patient positioning, materials to be swallowed, sequence of attempted swallows, and what to look for, including interpretation and documentation of the findings. Typically, the videofluoroscopic swallowing examination begins with the patient in a lateral (or semioblique) position in reference to the fluoroscopic image (Figure 10-2). This perspective affords an excellent view of the swallowing mechanism from the lips to cervical esophagus and provides the best view of the trachea separate from the esophagus. This view is beneficial in determining whether material enters the upper airway. After examination of the swallow in the lateral perspective, the patient is turned for an anterior view. This perspective permits excellent evaluation of symmetry along the swallowing mechanism. When the esophagus is imaged with the patient in a sitting position the extent of the view is often limited. In these situations, imaging is done with the patient in a standing or lying position depending on physical limitations of the patient or specific aspects of the dysphagia presentation. In fact, for some patients who can tolerate standing during the fluorographic examination without compromise, the entire examination can be done with the patient in a standing position. This situation permits a great degree of control in moving and positioning the patient. The key material used in the fluoroscopic swallow study is barium sulfate suspension. This is a positive contrast agent that is radiopaque. As a result, barium sulfate appears as black on the fluoroscopic image compared with negative contrast substances, such as air, which appear as varying shades of gray. Tissue and bone appear as shades of gray depending on their density. Figure 10-3 depicts the shades of the bolus in the mouth, various bony structures (including the hyoid bone), and the air spaces in the pharynx and the trachea. Regardless of the outcome of this food-versus-barium discussion, the importance of using a range of textures and volumes during the study cannot be overstated. It is well known that a normal swallowing mechanism adjusts to changes in bolus volume and/or texture.10–13 In the absence of this accommodation, a patient with dysphagia may demonstrate a variety of compensations or demonstrate the consequences of impaired physiology and the inability to compensate. Volumes used in fluoroscopic swallowing studies vary across published reports. One consideration is the average amount ingested in normal-swallowing adults. Published literature suggests that approximately 20 mL of liquid represents the average drink from a cup.14 Moreover, an average teaspoon is approximately 5 mL. Therefore, based on a functional perspective, it seems reasonable that the majority of swallow attempts would include volumes somewhere within this range unless clinical indications exist to use less or more material. In fact, results of a recent study15 suggested that swallows of a 5-mL bolus of thin barium liquid and a 5-mL bolus of nectar-thick barium liquid contributed the greatest amount of information to interpretation of 15 physiologic swallowing components. The author’s standard protocol has been to use 5 and 10 mL of each material and then allow the patient to drink freely from a cup or by a straw whenever feasible or clinically indicated. This choice of volume and consistency is based in part on the functional considerations previously mentioned and in consideration of a study suggesting that when using standard materials, 5-mL and 10-mL volumes of thin and thick liquid demonstrated the strongest associations between clinical signs of aspiration and observed aspiration during the videofluoroscopic swallowing study.16 In addition to varying volume, consistency—or viscosity—is varied across swallows. General categories of viscosity or textures include thin liquid, thickened liquid, paste or pudding, and masticated material.7 One barium product line has attempted to standardize the viscosity of barium sulfate liquids into thin, nectar, and honey. A paste material also is available in this product line. One benefit of these standardized barium products is consistency and reproducibility of repeated examinations both within and across patients. In short, use of standardized materials reduces variability across examinations that might result from utilization of different materials. Different protocols have suggested different sequences of events during the fluoroscopic swallowing study. For example, Logemann9 recommends beginning with thin liquids in progressive sequential amounts (1 mL, 3 mL, 5 mL, 10 mL). Once thin liquid swallows are completed, pudding and then masticated materials are evaluated. Palmer et al.5 began their fluoroscopic swallowing protocol with 5 mL of thick liquids (this category includes pudding material in their protocol), followed by thin liquid and then masticated materials. Martin-Harris et al.15 initiated their protocol with 5 mL of thin liquid followed by thicker liquids, pudding, and a masticated material. However, this group did caution that larger, thicker, and masticated materials were given to patients only if they demonstrated adequate airway protection and pharyngeal clearance on the thin liquid materials. The author agrees that a standard protocol is beneficial when completing the fluoroscopic swallowing, but recommends flexibility in the sequence of events to maximize the “diagnostic outcomes” for each patient. Described below is a general sequence of events used in the author’s standard protocol for the videofluoroscopic swallowing study. After this sequence of events is imaged from the lateral view, the patient is turned and viewed from the anterior perspective. From this view the patient is asked to sustain phonation or repeat the same vowel to visualize movement of the true vocal folds. Some patients are asked to phonate in a falsetto mode to evaluate medial movement of the lateral pharyngeal walls. Some are asked to perform a “trumpet” maneuver to evaluate potential weakness in the lateral pharyngeal walls. The trumpet maneuver is accomplished by asking the patient to lift the chin to provide a clear view of the entire pharynx. Then the patient is asked to puff the cheeks and blow as if playing a trumpet (Figure 10-4). Turning the head to each side during swallowing may assist in evaluating each hemipharynx and any effect on pharyngoesophageal segment (PES) opening. Materials used in the anterior view depend largely on the results of swallows examined with the lateral view. In general, not all materials are repeated with the change in orientation, but sufficient swallows are evaluated to assess symmetry, physiology, and the consequences of impaired movement.

Instrumental Swallowing Examinations

Videofluoroscopy and Endoscopy

CONSIDERATIONS FOR AN INSTRUMENTAL SWALLOWING EXAMINATION

Goals of Instrumental Swallowing Evaluations

Purposes of Instrumental Swallowing Examinations

VIDEOFLUOROSCOPIC SWALLOWING EXAMINATIONS

What’s in a Name?

Objectives of the Videofluoroscopic Swallowing Examination

Procedures for the Videofluoroscopic Swallowing Examination

Patient Positioning

Material Used in the Fluoroscopic Study

Sequencing the Events in the Fluoroscopic Study

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Instrumental Swallowing Examinations: Videofluoroscopy and Endoscopy