Chapter 6 Indications for and Contraindications to ERCP

The appropriate use of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and avoidance of this procedure when it is contraindicated or when there are alternative diagnostic procedures, is a quality issue for gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopists. The Standards of Practice guidelines of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) are widely regarded as the standard of care for GI endoscopists in the United States and have been widely adopted in other countries. Over the years the Standards of Practice and Training Committees of ASGE, and a Joint ASGE/American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy, have produced position statements that address issues relating to ERCP. The most recent of these are already more than 5 years old: The Role of ERCP in Diseases of the Biliary Tree and Pancreas (2005),1 ERCP Core Curriculum (2006),2 and Quality Indicators for Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (2006).3 At the top of the list of Quality Indicators in this last document has been “appropriate indication.” At the time of writing, the ASGE Standards of Practice Committee is in the process of revising its 2005 document. I had hoped to include a “sneak preview” of the updated 2012 ASGE Indications and Contraindications for ERCP in this chapter, but the document was still “in the works” when I had to finalize this chapter. Therefore I intend to review what has been proposed in the past and to highlight what has changed in the practice of ERCP since the last ASGE guidelines were promulgated.

It should be stated clearly that just because an ERCP is indicated, this does not mean that all ERCP endoscopists are competent to perform the procedure. Competence is a difficult attribute to define4 and is beyond the scope of this review. A 1996 prospective study of ERCP training, in which I participated, found that at least 180 to 200 supervised procedures were necessary for trainees to achieve minimum acceptable competence (defined as 80% success) in ERCP skills such as selective cannulation and biliary sphincterotomy.5 However, few experienced ERCP teachers believe that 200 procedures constitute anywhere near adequate training. Since 1996, ERCP practice has become overwhelmingly therapeutic; competence in ERCP now requires skill at placing pancreatic duct (PD) stents for prophylaxis against post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP), needle-knife papillotomy (NKP), and ampullectomy. A 2007 study from the United Kingdom found that only 66% of trainees achieved competence after performing 200 procedures.6 The authors concluded that “quality [of ERCP] suffers [in the UK] because there are too many trainees in too many low-volume ERCP centers.” This problem is not unique to Britain; there are many low-volume centers in the U.S. that claim to provide credentialable ERCP training. A Mayo Clinic study that evaluated the learning curve of a single trainee found that it took between 350 and 400 supervised procedures for the trainee to achieve consistent success at cannulation (≥80%)7; this rose to 96% after a further 300 procedures. In my opinion, this is a more realistic estimate of what it takes to develop expertise in ERCP. The following discussion of indications and contraindication assumes that the endoscopist has appropriate supervised training and experience in the necessary techniques and familiarity with the equipment required to perform them.

Indications for and Contraindications to ERCP

An understanding of indications and contraindications for any procedure is part of being a well-trained endoscopist, a fact recognized in 2002 ASGE guidelines on Methods of Granting Hospital Privileges for Performing Endoscopy.8 The list of attributes indicating satisfactory training in ERCP included “… a thorough understanding of the indications, contraindications, individual risk factors and benefit–risk considerations for the individual patient.” There are very few indications for purely diagnostic ERCP in modern practice. Therefore there is no role for the solely diagnostic ERCP endoscopist. As the technical demands of ERCP have increased, so have the range and complexity of tasks that the ERCP endoscopist is expected to master. All ERCP endoscopists need to know how to perform safe and effective biliary sphincterotomy, remove bile duct stones, dilate biliary strictures, place plastic and metal mesh biliary stents, and provide PEP prophylaxis with small-caliber PD stents. In the “old days,” many ERCP endoscopists avoided pancreatic intervention altogether. However, now that the benefits of PD stenting as prophylaxis against PEP have become clear from multiple published studies,9,10 the ability to place a PD stent is a necessary part of the modern ERCP endoscopist’s skill set.

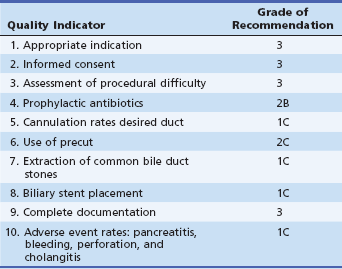

The authors of the 2006 ASGE/ACG Taskforce for Quality in Endoscopy publication Quality Indicators for Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography3 identified the level of confidence of each recommendation based on the available literature (Box 6.1). Laudable as this effort appears, solid evidence was frequently missing in support of what we consider important parts of the preparation for, performance of, and follow-up after ERCP (Table 6.1).

Box 6.1

Grades of Recommendation

1A. Clear. Randomized trials without important limitations. Strong recommendation; can be applied to most clinical settings. [Clear benefit]

1B. Clear. Randomized trials with important limitations (inconsistent results, nonfatal methodologic flaws). Strong recommendation; likely to apply to most practice settings. [Clear benefit]

1C+. Clear. Overwhelming evidence from observational studies. Strong recommendation; can apply to most practice settings in most situations. [Clear benefit]

1C. Clear. Observational studies. Intermediate-strength recommendation; may change when stronger evidence is available. [Clear benefit]

2A. Unclear. Randomized trials without important limitations. Intermediate-strength recommendation; best action may differ depending on circumstances or patients’ or societal values. [Unclear benefit]

2B. Unclear. Randomized trials with important limitations (inconsistent results, nonfatal methodologic flaws). Weak recommendation; alternative approaches may be better under some circumstances. [Unclear benefit]

2C. Unclear. Observational studies. Very weak recommendation; alternative approaches likely to be better under some circumstances. [Unclear benefit]

3. Unclear. Expert opinion only. Weak recommendation; likely to change as data become available. [Unclear benefit]

Modified from ASGE Training Committee. ERCP core curriculum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:361-376.

Table 6.1 Summary of Proposed Quality Indicators for ERCP

Modified from ASGE Training Committee. ERCP core curriculum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:361-376.

Another way of looking at such evidence is a simple A, B, C grading system, such as the one that the 2005 ASGE Practice Guideline: The Role of ERCP in Diseases of the Biliary Tract and the Pancreas1 offered: (A) prospective controlled trials; (B) observational studies; and (C) expert opinion. The ASGE offered the following position statements on ERCP:

ERCP is now a primarily therapeutic procedure for the management of pancreaticobiliary disorders (level C).

ERCP is now a primarily therapeutic procedure for the management of pancreaticobiliary disorders (level C).

Diagnostic ERCP should not be undertaken in the evaluation of pancreaticobiliary pain in the absence of objective findings on other imaging studies (level B).

Diagnostic ERCP should not be undertaken in the evaluation of pancreaticobiliary pain in the absence of objective findings on other imaging studies (level B).

Routine ERCP before laparoscopic cholecystectomy should not be performed (level B).

Routine ERCP before laparoscopic cholecystectomy should not be performed (level B).

Endoscopic therapy of postoperative biliary leaks and strictures should be undertaken as first-line therapy (level B).

Endoscopic therapy of postoperative biliary leaks and strictures should be undertaken as first-line therapy (level B).

ERCP plays an important role in patients with recurrent acute pancreatitis and can identify and in some cases treat underlying causes (level B).

ERCP plays an important role in patients with recurrent acute pancreatitis and can identify and in some cases treat underlying causes (level B).

ERCP is effective in treating symptomatic strictures in chronic pancreatitis (level B).

ERCP is effective in treating symptomatic strictures in chronic pancreatitis (level B).

ERCP is effective for the palliation of malignant biliary obstruction (level B), for which self-expanding metallic stents have longer patency than plastic stents (level A).

ERCP is effective for the palliation of malignant biliary obstruction (level B), for which self-expanding metallic stents have longer patency than plastic stents (level A).

ERCP can be used to diagnose and to treat symptomatic PD stones (level B).

ERCP can be used to diagnose and to treat symptomatic PD stones (level B).

PD disruptions or leaks can be effectively treated via the placement of bridging or transpapillary pancreatic stents (level B).

PD disruptions or leaks can be effectively treated via the placement of bridging or transpapillary pancreatic stents (level B).

ERCP is a highly effective tool to drain symptomatic pancreatic pseudocysts and, in selected patients, more complicated benign pancreatic fluid collections arising in patients with a history of pancreatitis (level B).

ERCP is a highly effective tool to drain symptomatic pancreatic pseudocysts and, in selected patients, more complicated benign pancreatic fluid collections arising in patients with a history of pancreatitis (level B).

Intraductal ultrasound and pancreatoscopy are useful adjunctive techniques for the diagnosis of pancreatic malignancies (level B).

Intraductal ultrasound and pancreatoscopy are useful adjunctive techniques for the diagnosis of pancreatic malignancies (level B).

ERCP can be performed safely in both children and pregnant women by experienced endoscopists. In both situations, radiation exposure should be minimized as much as possible (level B).

ERCP can be performed safely in both children and pregnant women by experienced endoscopists. In both situations, radiation exposure should be minimized as much as possible (level B).

Indications for ERCP

The recommended indications for ERCP in the ASGE/ACG Joint Taskforce document Quality Indicators for Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography3 are listed below (A through M) (Box 6.2). This alphabetic scale is unrelated to the quality of evidence A, B, C scale just discussed. I have added a few miscellaneous indications as an extra category, identified as N. Text added by me to clarify descriptions is in italics.

A. Jaundice thought to be the result of biliary obstruction

B. Clinical and biochemical or imaging data suggestive of pancreatic or biliary tract disease

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree