Chapter 38 Indeterminate Biliary Stricture

Biliary obstruction results from diverse benign and malignant processes and patients can present acutely or chronically with signs and symptoms ranging in severity (Box 38.1). The nature of an obstruction is often immediately clear at the time of initial investigation, while at other times obstruction is readily apparent but the nature of the pathologic process remains uncertain. No single definition exists for the term indeterminate stricture but it commonly refers to biliary strictures in patients in whom cross-sectional imaging is unrevealing (i.e., without an associated mass lesion) and without pathologic confirmation. Recent experience with inflammatory pancreatic masses may prompt expansion to include all strictures, including those with associated mass lesions, prior to histologic characterization.

When biliary obstruction is identified, an efficient approach to early diagnostic testing and management is important for reduction of morbidity and guidance of definitive therapy. Untreated obstructive cholestasis of even moderate degree can culminate in secondary biliary cirrhosis within several months.1,2 Patients with inadequately treated strictures also risk development of acute or chronic cholangitis, particularly following invasive testing.

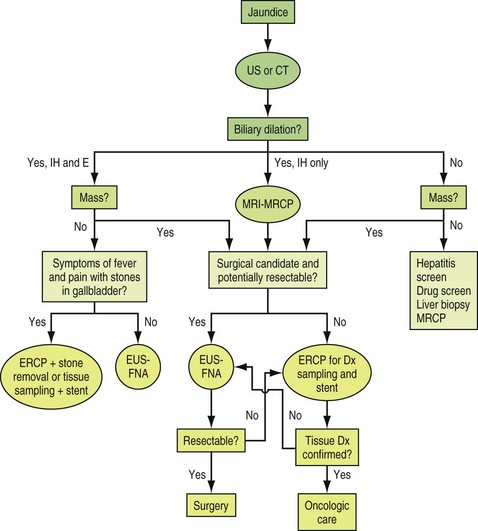

Key steps in the assessment and management of patients with indeterminate biliary strictures include characterization of the pathogenesis of the stricture, relief of biliary obstruction, and/or definitive treatment of the pathologic process—employing medical, endoscopic, percutaneous, or surgical means (Box 38.2). Stricture characterization and relief of obstruction are not independent pursuits but are typically accomplished in unison. Stricture characterization is based on historical features, laboratory testing, noninvasive and invasive imaging, and the use of various tissue sampling methods (Fig. 38.1).3

Historical Features

Historical features may contribute to both the correct diagnosis and the management strategy for newly identified biliary strictures (Box 38.3). Prior history of inflammatory bowel disease, complicated biliary surgery, or chronic pancreatitis suggest primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), postoperative strictures, and pancreatic compression of the common bile duct (CBD), respectively. An acute presentation in the early postoperative period or during an episode of pancreatitis suggests significant operative injury or stone-related obstruction whereas subacute but early (<3 months) presentations suggest inflammatory processes that may resolve with time. Hence minimally invasive and temporizing approaches may suffice in the latter case. Presentation more than 3 months after a prior insult suggests a more fibrotic and rigid stricture that may require more aggressive or prolonged therapy. Strictures that present in an occult or delayed fashion and those presenting without known predisposing factors all raise the specter of a malignant etiology. A waxing and waning presentation is suggestive of benignity whereas inexorable progression of symptoms associated with weight loss suggests malignant etiologies.

Laboratory Features

Very few serologic markers contribute to characterization of the benign or malignant nature of indeterminate biliary strictures. Cancer antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) is a serum moiety that is elevated in the settings of pancreatic and biliary carcinoma, cholangitis, and to a lesser degree pancreatitis.4 Marked CA 19-9 elevations above 1000 IU are seen only with cancer or florid cholangitis. Elevations above 100 IU are strongly suggestive of cancer in the absence of known pancreatitis or cholangitis. When an elevated CA 19-9 is detected in the setting of cholangitis, it should be reassessed following appropriate therapy of the infectious process.

Immunoglobulin G, subfraction 4 (IgG4) levels are often but not invariably elevated in autoimmune pancreatitis, which can cause biliary strictures that mimic those that occur with chronic pancreatitis of other etiologies or pancreatic cancer.5 Such strictures are often amenable to therapy using corticosteroids. IgG4-related cholangitis can mimic sclerosing cholangitis with multifocal strictures in any location. In a large Mayo Clinic series, such patients generally were older (mean age of 62 years) men (85%) presenting with obstructive jaundice (77%) associated with autoimmune pancreatitis (92%), increased serum IgG4 levels (74%), and abundant IgG4-positive cells in bile duct biopsy specimens (88%). At presentation, biliary strictures were confined to the intrapancreatic bile duct in 51% and to the hilum in 49%. Initial presentation was treated with steroids in 30 patients. Steroid therapy normalized liver enzyme levels in 61%; biliary stents could be removed in 17 of 18 patients but relapses occurred in 53% after steroid withdrawal. The presence of hilar strictures was predictive of relapse. Fifteen patients treated with steroids for relapse after steroid withdrawal responded; 7 patients on additional immunomodulatory drugs remained in steroid-free remission after a median follow-up period of 6 months.6

Noninvasive Cross-Sectional Imaging

Once a stricture is localized by cross-sectional imaging with US (or CT scanning), the next step in evaluation is highly dependent on clinical judgment as to whether the setting favors a benign or malignant process, the patient’s fitness for surgery, and the apparent resectability of the lesion based on initial studies. Ultrasonographic evidence of a stricture, without evidence of advanced cancer, is usually followed by abdominal CT scanning to define whether a mass exists and to provide initial staging information. If US demonstrates a distal unresectable mass, based on local-regional extension, hepatic metastasis, or associated ascites, then endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is usually performed for both tissue acquisition and palliation of obstructive jaundice. If US demonstrates a hilar mass, with or without evidence of unresectability, then magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is helpful to better define the level of the obstruction, assist with assessment of resectability, and guide the subsequent approach to invasive cholangiography, tissue sampling, and palliative stenting.7 An extrahepatic stricture without a mass in the setting of fever, apparent biliary pancreatitis, or gallbladder stones can often be evaluated directly with ERCP in anticipation of identifying an obstructing duct stone.

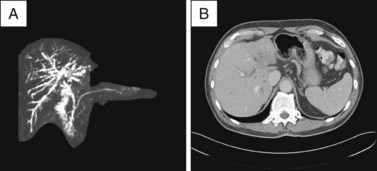

Abdominal CT scanning is commonly employed in patients with associated weight loss, fever, or significant pain, as it is particularly useful for identification and staging of extraductal mass lesions, inflammatory processes, and bile collections or leaks (Fig. 38.2). CT is also preferred over US in obese subjects. CT images, with routine inclusion of both axial and coronal cuts, are now very familiar to most clinicians. CT cholangiography is also available but infrequently used in the era of MRCP.

Abdominal MRI yields cross-sectional information analogous to CT scanning and can provide relatively sensitive cholangiographic images that usually allow determination of stricture location (Fig. 38.3). MRCP is the most sensitive noninvasive imaging test for biliary obstruction and duct stones; it approaches the sensitivity of ERCP for identification of biliary strictures.8 Studies differ, however, as to whether MRCP is inferior or equivalent to ERCP for the differentiation of benign and malignant lesions.8,9 When acquired and displayed by standard cross-sectional MRI images, information regarding extraductal pathology or extent of disease tends to be less readily interpreted by the nonradiologist than are CT images. MRCP has largely replaced diagnostic endoscopic cholangiography when there is no need for tissue acquisition, therapy, or dynamic measurements of motility. The primary benefit of MRCP is the avoidance of intubation, sedation, and the risk of pancreatitis. Other advantages of MRI over ERCP include the ability to display the anatomy of the ducts and the liver above a stricture even when complete obstruction is present and the ability to generate multiple perspectives or angles of view for the same lesion. A disadvantage of MRI is that the cholangiographic display includes all ducts, without the ability to localize images to the region of interest around a stricture, as is done with “early films” acquired during initial contrast instillation during ERCP. This sometimes makes interpretation of a central or a complex stricture difficult due to overlapping peripheral ducts that are of little consequence. Several studies have demonstrated the utility of MRCP as a guide to subsequent ERCP and palliative stent placement for hilar lesions7 (Fig. 38.4), as discussed in Chapter 37.

Fig. 38.3 Abdominal MRCP demonstrating a distal extrahepatic stricture with a “double-duct sign,” analogous to that seen on CT in Fig. 38.2.

Invasive Imaging Techniques

Invasive techniques for evaluation of the biliary tree include endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and traditional contrast-based cholangiography via percutaneous transhepatic (PTC) or endoscopic retrograde (ERCP) routes. Intraductal ultrasound (IDUS) and peroral cholangioscopy are specialized techniques employed during performance of ERCP and will be discussed in subsequent sections. Cholangioscopy is also discussed in Chapter 26.

EUS is useful for both diagnosis and staging of malignant biliary strictures. EUS is accomplished from the duodenal bulb and/or the antrum, depending on the patient’s anatomy. Radial or linear technology can be employed but the frequent use of fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is driving an evolution toward predominantly linear imaging. Malignancies are identified as hypoechoic masses or thickening of the bile duct wall. In one study of 40 indeterminate biliary strictures (24 malignant, 16 benign) EUS findings of a pancreatic head mass and/or an irregular bile duct were more sensitive than concurrent FNA sampling. EUS imaging alone was 88% sensitive and 100% specific for malignancy. Wall thickness greater than 3 mm was 79% sensitive and 79% specific for malignancy. The sensitivity of FNA was 47%, with 100% specificity and positive predictive value (PPV) but only 50% negative predictive value (NPV).10 In a comparative study of several modalities, EUS sensitivity and specificity (79% and 62%) were less than ERCP or MRCP but complementary to them.8 In contrast, a study evaluating EUS with FNA in 28 patients with nondiagnostic sampling of biliary strictures obtained during ERCP, PTC, or CT demonstrated 86% sensitivity, 100% specificity, 100% PPV, 57% NPV, and 88% accuracy for malignant lesions.11 Importantly, management was influenced in 84% of patients. Some but not all studies note a greater sensitivity of EUS-FNA for pancreatic lesions than for extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.12

A prospective observational study from a large tertiary hospital compared EUS versus CT and MRI for the detection of tumor and prediction of unresectability among 228 patients with biliary strictures, 81 of whom had cholangiocarcinoma (CCa). For those with available imaging, tumor detection was superior with EUS compared to triphasic CT (76 of 81 [94%] versus 23 of 75 [30%], respectively; p <0.001). MRI identified the tumor in 11 of 26 patients (42%; p = 0.07 versus EUS). EUS identified CCa in all 51 (100%) distal and 25 of 30 (83%) proximal tumors (p <0.01). The overall sensitivity of EUS-FNA for the diagnosis of CCa was 73% (95% confidence interval [CI] 62% to 82%). This was significantly higher in distal CCa compared with proximal CCa (81% versus 59%, respectively; p = 0.04). EUS correctly identified unresectability in 8 of 15 patients and correctly identified the 38 of 39 patients with resectable tumors (53% sensitivity and 97% specificity for unresectability). CT and/or MRI failed to detect unresectability in 6 of these 8 patients.13 EUS and CT are also complementary studies for staging and determination of resectability for distal biliary strictures due to pancreatic mass lesions.14

Percutaneous and EUS-guided FNA of bile duct lesions preclude subsequent management of cholangiocarcinoma with regimens that employ liver transplantation, due to the risk of seeding the extraductal needle track.15 In this potential setting, EUS-guided FNA is only used to sample periductal or hilar lymph nodes or other distant lesions that independently exclude the use of transplantation if positive. Hence, while not a primary imaging modality for biliary strictures, EUS with FNA is an important ancillary technique when diagnosis remains elusive and when staging for determination of resectability is sought.

Cholangiography is the mainstay for diagnosis and characterization of extrahepatic biliary lesions of all types. Endoscopic and percutaneous approaches to cholangiography are complementary studies and on occasion both will be necessary to characterize and treat difficult biliary lesions (Box 38.4). In general, proximal lesions that appear to involve the hilar region are best investigated initially with noninvasive MRCP, as this study provides directional guidance for subsequent invasive imaging and palliation7 and avoids the risk of cholangitis that occurs with ERCP when contrast is injected into areas that may not be drainable. However, preoperative planning for hilar lesions may still require the clarity of contrast-based cholangiography (ERCP or PTC).

Box 38.4

Indications and Favored Settings for Endoscopic versus Percutaneous Cholangiographic Approach to Biliary Strictures

Settings Favoring Percutaneous Approach (PTC)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree