Incarcerated Femoral Hernia

Shirin Towfigh

Femoral hernias are rare, comprising 4% of all groin hernias. Patients with femoral hernias are on average older than those with inguinal hernias (63 year vs. 59 years), and twice as many are over age 80 (19% vs. 8.5%). This is important because 35% of femoral hernias require emergent surgery due to incarceration or strangulation, compared to 5% of inguinal hernias. Also, 18% of emergent femoral hernia repairs require a bowel resection, as compared to 5% of inguinal hernias.

Historically, mortality rates as high as 25% had been reported, and modern day mortality rate for femoral hernia surgery is 3%, which is ten-fold higher than other hernia repairs. Thus, watchful waiting is not advocated for femoral hernias and early elective repair is recommended whenever possible.

Patients with incarcerated or strangulated femoral hernias are often misdiagnosed, diagnosed late, or die without diagnosis. In thin patients, an irreducible, often painful bulge is seen in the groin. The hernia has a tendency to migrate anteriorly; thus on examination this bulge may present as a mass above the inguinal ligament and misdiagnosed preoperatively as an incarcerated inguinal hernia. In obese patients, it is common to miss a small incarcerated or strangulated hernia.

With the liberal use of CT scanning for patients with abdominal pain, the diagnosis of an incarcerated to strangulated femoral hernia may be formed preoperatively. This will help in planning for surgery, as the surgical approach differs based on the clinical scenario.

Strangulated hernia. If a strangulated hernia is diagnosed clinically or radiologically preoperative, the preferred choices of repair include: (1) Open preperitoneal approach, or (2) laparoscopic transabdominal approach. With both of these techniques, the hernia contents may be examined for signs of strangulation and addressed through the same approach while performing the femoral hernia repair. Also, a concomitant inguinal hernia (usually direct) may be diagnosed and repaired.

Incarcerated hernia. If there is clearly no clinical sign of strangulation, such as sepsis, skin erythema, and no radiologic suggestion on CT scan, the choices of repair are much greater. These include: (1) Infrainguinal approach, (2) transinguinal approach, (3) open preperitoneal approach, (4) laparoscopic preperitoneal or transabdominal approach.

Recurrent hernia. Femoral hernias may be missed after repair of an inguinal hernia, may occur after repair of a direct hernia, or may be recurrent. In these situations, a mesh repair is highly encouraged. These may be performed via the approaches listed below.

The history of femoral hernia repair dates back to 1876 when Thomas Annandale plugged a femoral hernia defect with the hernia sac excised from a concomitant inguinal hernia repair. In 1883, Lawson Tait primarily repaired a femoral hernia using a silk suture; William Cheyne placed a pectineus muscle plug in 1892, and Howard Kelly inserted an agate marble in a femoral defect in 1898. Below are the most commonly performed procedures in modern day femoral hernia repair.

Infrainguinal Approach

Commonly referred to as the “low” or “Lockwood” approach, this repair has been described by Marcy, Bassini, Lockwood, and Lichtenstein. This approach should be reserved for elective repairs or simple incarcerated hernias without evidence of strangulation. The low approach is more appropriately applied to women, as men are more likely to have a concomitant inguinal hernia that may need to be addressed at the same setting.

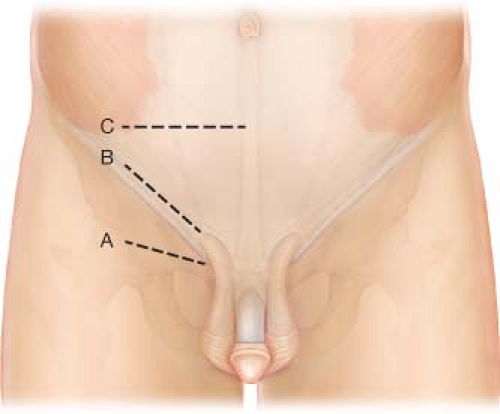

A transverse skin incision is made at the level of the bulge, 4 cm wide (Fig. 9.1A and Fig. 9.2). The fat is meticulously dissected with electrocautery until the sac is encountered. Small vessels in communication with the long saphenous vein are ligated. The femoral vein is identified early and gently retracted to avoid injuring it throughout the rest of the procedure. The sac is dissected deep toward the femoral canal orifice. Pull on the sac toward you and laterally in order to inspect the medial wall of the femoral sac, which may contain the bladder wall. The neck of the sac is dissected circumferentially and it is allowed to retract back through the canal into the retroperitoneal space.

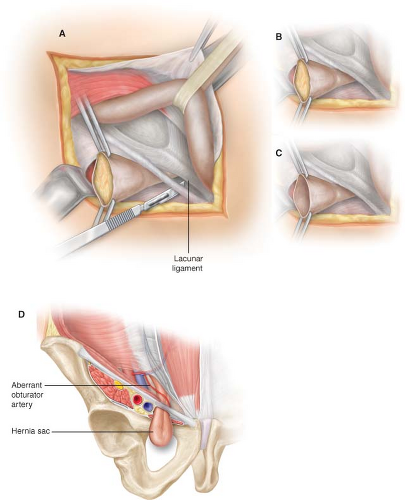

Often, the sac is not reducible due to the tight femoral orifice. The orifice should initially be bluntly widened by passing a dissector through the orifice and spreading it open. If this is not successful, the lacunar ligament of Gimbernat, which is immediately medial to the canal, can be incised transversely (Fig. 9.3). This is not a

risk-free procedure, as there may be an aberrant obturator artery (less than 1/3) in this plane. An alternative procedure is anterior incision (without transection) of the inguinal ligament.

Figure 9.1 Location of incisions based on approach. A: infrainguinal approach; B: transinguinal approach; C: nyhus transabdominal preperitoneal approach.

Figure 9.3 Lateral incision of the lacunar ligament of Gimbernat (A–C). Note the variable anatomy of the obturator artery as it relates to lacunar ligament (D).

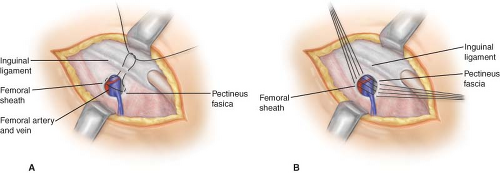

Figure 9.4 Primary repair of femoral hernia using the low infrainguinal approach. A: Macy purse-string; B: Bassini

Opening of the hernia sac is not necessary, unless there is a question of strangulated content. Similar to inguinal hernias, a high dissection and reduction of the sac is adequate. However, if the contents cannot be reduced or there is a need to inspect the hernia content, then carefully open the sac, as the bladder may be involved with the medial wall. Fluid will likely exude from the sac.

Primary repair. Primary closure of the defect is performed with non-absorbable suture. It is known to have a high recurrence rate and can cause significant postoperative pain due to the tension in this region. It should be reserved for defects 1 cm or less.

Macy purse-string. The external oblique fascia is grasped and elevated, demonstrating the ilioinguinal ligament. A single suture is used, starting from the ilioinguinal ligament superiorly, the lacunar ligament of Gimbernat medially, the pectineal fascia inferiorly, and the femoral sheath laterally, and then back onto the ilioinguinal ligament (Fig. 9.4A).

Bassini repair. The external oblique fascia is grasped and elevated for exposure. Interrupted sutures approximate the ilioinguinal ligament (superiorly) with pectineal fascia (inferiorly) (Fig. 9.4B).

Mesh Repair. Since primary repair has a three-fold higher recurrence rate than mesh repair, larger hernias and recurrent hernias should be repaired with mesh.

Lichtenstein plug. A 2 × 20 cm flat polypropylene mesh is rolled and snugly placed into the femoral orifice (Fig. 9.5). It is sutured full-thickness in three places: Ilioinguinal ligament (superiorly), lacunar ligament of Gimbernat (medially), and pectineus fascia (inferiorly).

Mesh Plug. A pre-made shuttle-cock type plug, originally designed by Robbins and Rutkow, is inserted into the femoral defect. The typical size used is a small or medium plug. The inner leaflets may be trimmed to reduce the bulk of the mesh as needed. The outer leaflet of the plug may be left within the canal, as originally described, or pushed deep through the femoral ring and allowed to spring open, covering the femoral vessels laterally, the lacunar ligament medially, and Cooper’s ligament inferiorly (see Chapter 3, Plug and Patch Inguinal Hernia Repair). The inner leaflets are sewn similar to the Lichtenstein plug.

In my experience and others, primary repair of anything but the smallest of femoral hernias causes severe and at times disabling groin pain due to undue tension. At the same time, I do not advocate placing a large bulky mesh in the femoral canal, as this may cause pain due to mass effect, venous obstruction, or even deep vein thrombosis. My preference for elective or non-strangulated hernia repairs is a modification of the

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree