Hernia in Infants

Robert Acton

Daniel Stephens

Introduction

When thinking of hernias in infants primarily three hernias come to mind: Straightforward routine indirect hernias in term infants, giant pantalooning hernias in preterm infants, and umbilical hernias in both. These hernias in infants will present similarly to those in adults; however, the pathogenesis, treatment, and outcomes differ significantly. Both types of inguinal and umbilical hernias are discussed in this chapter.

Inguinal Hernias

Introduction

Inguinal hernia repair is one of the commonest procedures performed by pediatric surgeons and helps to define the specialty. The incidence ranges from 1% to 3% in children—about 1% in females, but up to 5% to 6% in males, with approximately 80% of hernias occurring in males. There is a right-sided predominance, which is attributed to the later decent of the right testes as compared to the left. The proposed etiology is failure of the processus vaginalis to obliterate. As such, indirect inguinal hernias represent 99% of all hernias in infancy. The incidence is also increased in preterm infants, with an estimated incidence of 12% at 32 weeks and up to 21% at 27 weeks’ post-conceptional age. Conditions leading to increased intraabdominal pressure, including chronic cough, ascites, ventriculo-peritoneal shunts, and peritoneal dialysis also lead to increased incidence.

As the embryonic testis descends from its origin in the lumbar retroperitoneum under the influence of calcitonin gene–related peptide, it is preceded by a diverticulum of the parietal peritoneum. This peritoneum becomes the tunica and the processus vaginalis. The processus normally obliterates by 35 weeks of gestation. This timing of normal obliteration explains the increased incidence of hernias within preterm infants. When obliteration fails or is only partial, the result is either hydrocele or an indirect inguinal hernia.

Indications/Contraindications

The diagnosis of hernia in a child depends highly on the history, generally obtained from the parents or caretakers. The history often includes a report of a fluctuating groin bulge that varies with coughing, crying, sneezing, or valsalva. Office examination may not always reveal this bulge, but a definitive history alone may suffice

as an indication for elective repair. In regards to preterm infants within the NICU the history is very similar, that of an inguinal bulge that quickly becomes very apparent on examination.

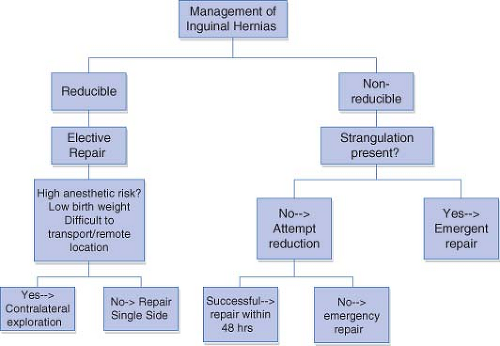

Physical examination may reveal a thickening or slipperiness in the groin, the so-called “silken cord sign.” Incarceration or obstruction is generally quite apparent and an indication for attempted reduction. If unsuccessful, exploration and repair should be performed emergently. If attempts at reduction are successful, the hernia should be repaired on a more urgent scheduled basis, often within 24 to 48 hours.

Hydrocele may be easily confused with an indirect hernia in males and trans-illumination may be deceiving. Hydroceles should not reduce or reduce very slowly depending on the size of the communication. Ultrasound may have utility in this regard if there is confusion about the diagnosis. Hydrocele alone, without a hernia, is not an indication for repair in neonates and small children under the age of 1, as most hydroceles will resolve within 1 to 2 years; however, persistence beyond this age is an indication for repair.

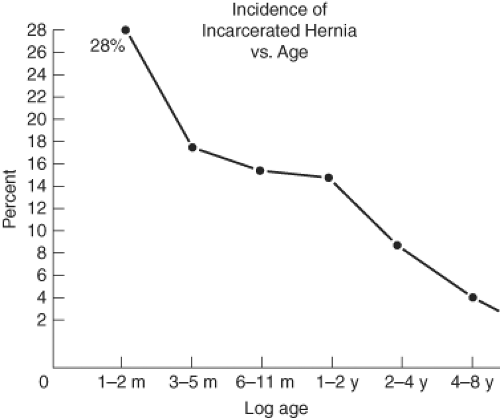

Timing of repair in preterm and term infants has been a subject of ongoing discussion. In the absence of incarceration or obstruction, some surgeons may elect to wait until the patient is older and better able to tolerate general anesthesia and be repaired as an outpatient, while others may advocate for repair just prior to discharge from the NICU or hospital. The degree of patient co-morbidities must be weighed against the risk of incarceration or obstruction if elective repair is delayed. The risk of incarceration is significantly higher when repair is delayed beyond 40 weeks’ gestational age; therefore, repair should generally take place prior to that point (Figs. 11.1, 11.2).

Preoperative Planning

Generally, no preoperative imaging is required if the history or examination supports the diagnosis. If the history or examination is equivocal, ultrasound may be a useful adjunct to differentiate a hydrocele from a hernia.

Preoperative laboratory studies may be limited to simply a hemoglobin/hematocrit to rule out anemia in an infant with no other medical issues. Certainly, if the infant has other co-morbidities such as congenital heart disease or bronchopulmonary dysplasia and is on diuretics electrolytes should also be checked. Coagulation studies are almost never needed.

Anesthetic consideration should include spinal or regional anesthesia, especially for preterm babies, those who have had prolonged ventilator support, or those

with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Caudal anesthesia can also be useful in postoperative pain control. Local anesthetic as well as narcotic can be administered to compliment intraoperative and postoperative analgesia.

Figure 11.2 The inverse relationship between age and risk of incarceration supports the practice of early elective repair of inguinal hernias.

Prophylactic antibiotics are not routinely indicated unless the indication for the procedure is incarceration or strangulation. In this instance, broad spectrum antibiotics and nasogastric decompression should be considered.

Routine contralateral exploration in infants is evolving toward selective contralateral exploration as the approach taken by an increasing number of pediatric surgeons. This approach takes into consideration the variably increased risk of an asymptomatic, contralateral hernia associated with left-sided hernias, younger infants, female patients, low birth weight babies, children with the increased intraabdominal pressure problems, and those that are difficult to transport. The action of contralateral exploration must be balanced against the risk of a second general anesthetic if another hernia is found, the risk of possible incarceration or strangulation that may be prevented by prophylactic exploration, and the risk of complication from unnecessary exploration such as injury to the vas deferens. Recent studies have demonstrated that the subsequent risk of developing a contralateral hernia is lower than once believed. This information is the main reason most surgeons are using a selective approach for contralateral exploration.

Surgery

Reduction

Incarceration is an indication for more urgent repair. Prior to repair, an attempt at reduction should be made. If the hernia is successfully reduced, the operation may take place in 24 to 48 hours after swelling is reduced and allows the procedure to be performed on an urgent as opposed to an emergent basis. If there is suspicion of strangulation, reduction should not be attempted until the operating room where the two limbs of the bowel can be controlled to prevent intraabdominal spillage of bowel contents.

Contrary to the common mashing, pushing, and pressure that are often performed to attempt reduction, traction of the hernia mass, testicle, or scrotal skin should be applied parallel to the inguinal canal with one hand and gentle pressure with the other hand should be applied for reduction. While stretching the scrotum toward the contralateral leg, the other hand should be used to apply pressure along the neck of the hernia near the external ring. Constant pressure should be applied for some time to reduce the amount of edema and empty the bowel luminal contents to aid in reduction. Then, with constant pressure along the inguinal canal with the other hand, pressure is applied to the bottom of the hernia contents until it is reduced. Once the loops are emptied of gas and succus, the loops essentially pull themselves back into the abdomen. A successful

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree