The overlap of pain and urinary voiding symptoms is common for urologic patients. The etiology of these syndromes is frequently multifactorial and due to disorders of the bladder and/or prostate. The evaluation and treatment of these syndromes continues to evolve. Here we summarize the general approach to evaluation and treatment of these pain syndromes.

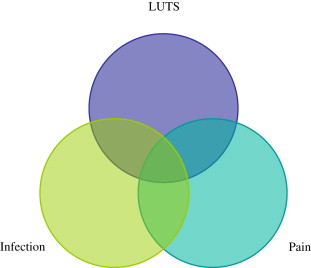

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) with associated lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), the focus of this issue of the Urologic Clinics of North America , is one of the most common conditions encountered by the practicing urologist. Indeed, as men age, the prevalence of BPH increases proportionally from 0% of men in their 30s to 88% of men in their 80s. A certain subset of men with BPH have LUTS that are bothersome enough to seek evaluation. However, LUTS by themselves are not specific for BPH and other lower urinary tract processes may be associated with similar symptoms. Some men with LUTS also have pelvic pain. Urinary tract infection may coexist and compound these symptoms. As shown in Fig. 1 , there is a cohort of men who have pain and infection, as well as LUTS, and any combination thereof.

The confluence of pain, infection, and voiding symptoms are commonly encountered in practice. Prostatitis, either acute or chronic bacterial, or chronic prostatitis (what is now called chronic pelvic pain syndrome [CPPS]) accounts for approximately 2 million outpatient visits per year in the United States. Despite the prevalence of these symptoms, diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of many of these genitourinary conditions remain difficult. Indeed, while research is underway to gain a clearer understanding of the pathophysiology, there are as yet no clear therapies for many of these disorders.

As with many other areas of medicine, the “treatment of pain” is particularly challenging because often the pain stems from multiple factors. Chronic pain disorders, such as fibromyalgia, inflammatory bowel syndrome, and interstitial cystitis, lead to reorganization of neurons involved in the processing of pain. Functional magnetic resonance studies done in our laboratory evaluating patients with CPPS and interstitial cystitis show distinct patterns in bilateral anterior insula and anterior cingulate cortex in patients experiencing chronic pelvic pain. This article assesses the approach to evaluation and treatment of the patient population with LUTS and chronic pelvic pain, with or without infection.

The general principles in the approach to genitourinary pain syndromes are fairly similar: Clinicians should be attentive and responsive to the needs of the patient, validated questionnaires should be used to quantify symptoms and assess progress, treatable etiologies should be identified and treated, and multimodal approaches should be used for long-term management.

Prostatitis and chronic pelvic pain syndrome

Epidemiology and Presentation

In 1995, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) developed a standard definition and classification of prostatitis syndromes, including a new category for asymptomatic patients with prostatic inflammation. Prostatitis has been categorized into four clinical entities, with category III incorporating CPPS. This serves as a framework for diagnosing, treating, and performing research in prostatitis syndromes ( Table 1 ). The NIH categories are as follows:

Category I: acute bacterial prostatitis (rare, 2%–5% of cases). Acute infection of the prostate gland marked by a combination of local symptoms (eg, dysuria, urinary frequency, and suprapubic/pelvic/perineal pain) and systemic symptoms (eg, fevers, chills, malaise); uropathogen typically identified as causal organism; responsive to antimicrobial therapy. Positive urine culture alone of 1000 or more colony forming units (cfu) per milliliter of urine is sufficient for confirming the diagnosis of acute bacterial prostatitis. Expressed prostatic secretions should not be obtained because of the theoretical concern for worsening sepsis.

Category II: chronic bacterial prostatitis (rare, 2%–5% of cases). Chronic infection of the prostate gland, characterized by intermittent local symptoms (eg, dysuria, urinary frequency, prostatic and suprapubic/pelvic/perineal pain); intermittent urinary tract infection (≥1000 cfu/mL of urine); or postmassage urine bacteria counts at 10-fold increase over concentration in the urethral urine. Uropathogen is typically identified in expressed prostatic secretions; normally responsive to antimicrobial therapy.

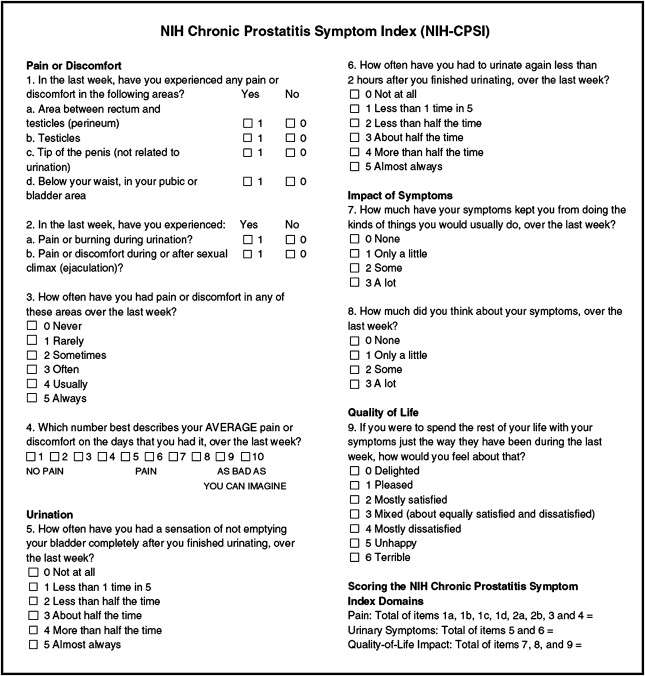

Category III: chronic nonbacterial prostatitis/CPPS (CP/CPPS) (common, 90%–95% of cases). Syndrome involving local symptoms (pelvic pain, urinary voiding symptoms, and ejaculatory symptoms); no identifiable uropathogen or infectious cause; treatment often fails to alleviate symptoms. The NIH Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI) questionnaire ( Fig. 3 ) is the primary validated tool used to quantify the severity of category III prostatitis. Category III is subdivided into inflammatory (IIIA) and noninflammatory (IIIB) prostatitis based on the presence or absence of leukocytes in the expressed prostatic fluid or ejaculate.

Category IV: asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis (prevalence unknown). Incidental observation of leukocytes in prostate secretions or prostate tissue obtained during evaluation for other disorders, (eg, for elevated prostate-specific antigen [PSA]). No infectious pathogens present; no treatment necessary.

| NIH Classification of Prostatitis Syndrome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Class | Bladder Urine Midstream (VB2) Specimen | Expressed Prostatic Secretions | NIH Classification (1995) | ||

| Culture | WBC | Culture | WBC | ||

| ABP | + | + | Not recommended | NIH category I | |

| CBP | 0 | 0 | + a | + b | NIH category II |

| NBP | 0 | 0 | 0 | + c | NIH category IIIa |

| Prostadynia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NIH category IIIb |

| Not described | ± | ± | NIH category IV (asymptomatic) | ||

c About 50% of patients have white blood cells in expressed prostatic secretions.

Evaluation and Diagnosis

Acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis

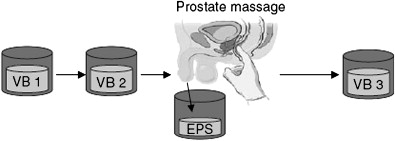

Acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis are most commonly caused by Escherichia coli , identified in 65% to 80% of infections, with Pseudomonas aeruginosa , Serratia spp, Klebsiella spp, and Enterobacter aerogenes making up another 10% to 15%. Acute bacterial prostatitis is usually dramatic in its presentation, often presenting with both lower urinary tract infection and generalized sepsis. Chronic bacterial prostatitis is usually associated with recurrent urinary tract infections bracketed by asymptomatic periods. Positive bacterial cultures from prostatic secretions (Meares, Stamey test, Fig. 2 ) confirm the diagnosis. Because of the possibility of urinary tract abnormalities in men with urinary tract infection, patients require CT and cystoscopy.

Chronic pelvic pain syndrome

The evaluation of CPPS involves administration of the NIH-CPSI questionnaire ( Fig. 3 ), a history and physical examination (with a focus on genitourinary examination), digital rectal examination, urinalysis, and four-glass Meares-Stamey localization cultures. The four-glass localization test involves the sequential collection of urine and prostatic fluid specimens, before, during, and after prostatic massage, and provides fluid and culture data to enable correct categorization of CPPS (see Fig. 2 and Table 1 ). Men with bacteria exclusively in the expressed prostatic secretions have CPPS and should be treated with appropriate antimicrobial therapy for a minimum of 4 weeks. Colony count in expressed prostatic secretions that exceed counts of midstream urine culture (VB2) by 10-fold or more are significant. Contamination from urethra is common. Therefore, it is essential that the number of colony forming units in the first 10 mL of urine (VB1) is known and that the expressed prostatic secretions or first 10 mL of urine after prostatic massage (VB3) exceeds the number of colony forming units in the VB1 by 10-fold or more.

In 1999, the NIH Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network (CPCRN) developed an instrument to measure the symptoms and quality of life of CPPS for use in research protocols as well as clinical practice. The result of this effort is the NIH-CPSI, which is administered as a questionnaire and has subsequently been validated in several studies. Our recommendation is that this validated tool be incorporated into the evaluation to quantify initial symptoms and monitor response to therapy.

Treatment

Category I prostatitis

Treatment of acute bacterial prostatitis involves hospitalization if there is evidence of generalized sepsis necessitating blood and urine cultures plus parenteral antimicrobial therapy. Urinary drainage is necessary when patients present with urinary retention related to acute prostatic inflammation. It is reasonable to attempt gentle passage of a small Foley catheter. If catheter placement fails, a urologic consultation for suprapubic drainage should be initiated. Should patients fail to improve clinically after 1 to 2 days, CT or MRI should be performed to rule out prostatic abscess, which requires surgical drainage. Prostatic abscess occurs primarily in immunocompromised patients, particularly men with HIV. From 5% to 10% of men with acute bacterial prostatitis progress to chronic bacterial prostatitis. Following resolution of symptoms and return of urine culture data, a 3- to 4-week course of outpatient antimicrobials is indicated.

Category II prostatitis

Chronic bacterial prostatitis often responds to treatment with a 4- to 8-week course of prostate penetrating antimicrobials, such as fluoroquinolones or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX). Fluoroquinolones demonstrate a 60% to 80% cure rate for category II prostatitis. For those who fail treatment, usually with recurrence, investigational treatments, such as transurethral resection of the prostate, or long-term suppressive antimicrobials may offer benefit.

Category III prostatitis

There are no formal guidelines for the management of CPPS and no proven therapies. Though category III prostatitis has been broken down into inflammatory (IIIa) and noninflammatory (IIIb) prostatitis based on the presence or absence of leukocytes in expressed prostatic fluid, this has not proven to be of much clinical utility. Numerous trials have failed to demonstrate efficacy of antimicrobials, alpha-blockers, anti-inflammatories, phytotherapy, biofeedback, thermal therapies, and pelvic floor training. A recently completed multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial looking at alfuzosin for the treatment of chronic prostatitis–pelvic pain syndrome showed no benefit over placebo.

If a patient has significant LUTS, goal-directed therapy should be considered and alpha-blockers may offer some benefit. Pelvic floor physical therapy may also be beneficial. Newer classes of medications, such as pregabalin used in the treatment of fibromyalgia and postherpetic neuralgia, show some promising preliminary data in this population as well.

Category IV: asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis

No treatment is indicated for this category in the absence of symptoms, this diagnosis being primarily of research interest.

Interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome

Epidemiology and Presentation

Interstitial cystitis, also known as painful bladder syndrome, is a chronic bladder condition characterized by suprapubic pain and urinary symptoms of frequency, urgency, and nocturia, in the absence of infection and malignancy. It is predominantly found in women with a 10:1 female/male ratio and a prevalence of 0.01% to 0.50% in the female population. In 1987, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) developed for research purposes consensus criteria for the diagnosis of interstitial cystitis. These relatively conservative criteria facilitated identification of a homogenous population. However, in clinical practice, the diagnosis and subsequent treatment are often more individualized with less stringent criteria, most notably not requiring cystoscopy and hydrodistension under general anesthesia for the diagnosis of interstitial cystitis. Some advocate that the NIDDK criteria used alone are far too restrictive to be used in clinical practice and would underdiagnose as many as 40% of patients. Despite these limitations, the NIDDK criteria have formed the basis for the diagnosis of interstitial cystitis, and have led to expanded research for this condition. The following are the NIDDK criteria for interstitial cystitis:

Inclusion criteria

- 1.

Cystoscopy: glomerulations and/or classic Hunner ulcer (examination for glomerulations must be done after hydrodistension under general anesthesia to 80–100 cm water for 1 to 2 minutes)

- 2.

Symptoms: bladder pain and/or urinary urgency

Exclusion criteria

- 1.

Bladder capacity greater than 350 mL on awake cystometry

- 2.

Absence of an intense urge to void with the bladder filled to 100 mL during cystometry using a fill rate of 30 to 100 mL/min

- 3.

Demonstration of phasic involuntary bladder contractions on cystometry using the fill rate described in number 2

- 4.

Duration of symptoms less than 9 months

- 5.

Absence of nocturia

- 6.

Symptoms relieved by antimicrobials, urinary antiseptics, anticholinergics, or antispasmodics

- 7.

Frequency of urination of less than eight times a day while awake

- 8.

Diagnosis of bacterial cystitis or prostatitis within a 3-month period

- 9.

Bladder or ureteral calculi

- 10.

Active genital herpes

- 11.

Uterine, cervical, vaginal, or urethral cancer

- 12.

Urethral diverticulum

- 13.

Cyclophosphamide or any type of chemical cystitis

- 14.

Tuberculous cystitis

- 15.

Radiation cystitis

- 16.

Benign or malignant bladder tumors

- 17.

Vaginitis

- 18.

Age less than 18 years

The International Continence Society definition of painful bladder syndrome is “the complaint of suprapubic pain related to filling, accompanied by other symptoms such as increased daytime and night-time frequency, in the absence of proven urinary infection or other obvious pathology.”

Evaluation and Diagnosis

The patient with suspected interstitial cystitis should have a history and focused physical examination. The history should include review of fluid intake and output; diet (caffeine); pain and voiding symptoms; history of urinary tract infections, stones, or chemical cystitis; and sexual history (dyspareunia or abuse). There are validated symptoms questionnaires, such as the O’Leary-Sant Questionnaire and Problem Index, the University of Wisconsin Interstitial Cystitis Scale, and the Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency Patient Symptom Scale, which may be useful in following patients with interstitial cystitis. Physical examination should focus on the genitourinary examination and include a pelvic examination in women and a digital rectal examination in men. Mandatory laboratory analysis involves a urinalysis and midstream urine culture to rule out infection and other etiologies of pain. In addition, we recommend cytology to rule out tumors, a symptom questionnaire, and a voiding diary, plus or minus cystoscopy with hydrodistension and biopsies. Optional evaluations include the potassium sensitivity test, which is used to detect abnormal permeability of the urothelium, as well as urodynamics and pelvic ultrasound. The diagnosis of interstitial cystitis is established based on exclusion of other etiologies and significant findings based on history and cystoscopy.

Treatments

Conservative therapy, including dietary modification, stress reduction, keeping a voiding log and adjusting fluid intake as necessary, consciously trying to expand the interval of voids, and pelvic floor muscle training, may help some patients with mainly urinary symptoms. Dietary modification involves identifying exacerbating foods and avoiding them. Some notable offenders include caffeine, alcohol, spicy foods, and urine acidifiers, such as cranberry juice. Case control studies suggest that high levels of stress may exacerbate interstitial cystitis symptoms. Thus, some advocate stress reduction. Though no microorganisms have been directly linked to interstitial cystitis, there are some who believe that they may play a role in the initiation and propagation of symptoms, and thus an empiric trial of antimicrobials is reasonable.

Tricyclic antidepressants, amitriptyline being the most widely studied, have showed fairly good response rates, with 42% of patients noting a greater than 30% improvement in symptoms (a clinically relevant change) on validated questionnaires in a randomized control trial of amitriptyline compared with placebo. Other noncontrolled studies have reported success rates from 64% to 90%, though response is less clearly defined. The basis for amitriptyline’s action is believed to be its central and peripheral anticholinergic properties, its blockage of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake, its sedative properties, and its antihistamine effects. The recommended dosage is 10 to 150 mg daily at bedtime titrated to response and side effects.

Other oral medications that have shown benefit in the treatment of interstitial cystitis include antihistamines, H1 and H2 antagonists, and long-term analgesics. Hydroxyzine (a first-generation H1 antagonist) in initial studies showed a dramatic response with improvements in almost all parameters by 30% or more ; subsequent controlled studies, including an NIDDK placebo-controlled trial, failed to confirm these findings. Cimetidine, an H2 antagonist, showed significant improvement in symptom scores from 19 of 35 to 11 of 35 ( P <.001) though no histologic changes on biopsy in a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. However, the etiology of this improvement remains unclear. Most patients benefit from judicious pain management using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and opioids.

Use of pentosan polysulfate for the treatment of interstitial cystitis is based on the concept that interstitial cystitis results from defects in the epithelial permeability barriers, particularly the glycosylaminoglycan layer, allowing urinary constituents to enter the bladder wall and contribute to the inflammation and sensory stimulation of interstitial cystitis. Pentosan polysulfate adheres to the luminal side of the bladder mucosa, thus enhancing or maintaining the permeability barrier of the bladder mucosa. Two placebo-controlled multicenter trials in the United States have demonstrated marginal evidence to support its use, with an improvement of 32% in the treatment group versus 16% with placebo. A subsequent randomized study, published by Nickels et al in 2005, suggested a significant benefit with a 30% overall reduction in symptom scores, and a reduction in severity of symptoms. This response was not dose dependent; thus Nickels recommends the 300-mg dose, as higher doses are associated with increased side effects.

Intravesical therapy for interstitial cystitis has demonstrated limited success in randomized controlled trials. A recent Cochrane meta-analysis of intravesical treatments for interstitial cystitis reviewed dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), heparinoids, pentosan polysulfate, capsaicin and resiniferatoxin (RTX), BCG, and others. The primary outcome measures were pain and bladder capacity, with urinary symptoms as a secondary outcome measure. Two trials demonstrated no advantage of RTX over placebo. One crossover trial showed benefit of intravesical DMSO over placebo and noted a 93% objective improvement versus 35% with saline, and 53% to 18% subjective improvement. However, all patients had fairly mild disease, and “improvement” was determined without a validated questionnaire. Despite this, DMSO continues to be used in practice because of its overall safety and lack of side effects. BCG did seem to suggest a benefit in two trials, but the benefit was not statistically significant in either. Pentosan polysulfate instillation did not result in significantly different pain symptoms, but did result in a minimal 33-mL increased bladder capacity, of unknown clinical significance. Thus, of all the intravesical therapies, DMSO seems to be the most efficacious, though randomized controlled trials need to be conducted.

Surgical therapies may offer some benefit to the refractory patient. Neuromodulation with placement of sacral nerve stimulators have been mildly successful in some small uncontrolled trials. These neuromodulation therapies appear promising, but require further investigation. As a last resort, urinary diversion and cystectomy are an option for the most severely afflicted patients, and the surgeon should be confident that the source of the pain is indeed from the bladder. The patient should be heavily counseled about quality-of-life issues involved in making such a decision, which should be made only after all other options have been exhausted. Additionally, pelvic pain can persist despite cystectomy in some patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree