ESOPHAGUS

ESOPHAGUS

Upper gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, heartburn, and epigastric pain are common in patients with chronic kidney disease. In addition to dialysis-related nausea and vomiting, potential esophageal causes of these symptoms include GERD or reflux esophagitis and esophageal motility disorders.

Multiple studies have found an increased prevalence of GERD-related symptoms in chronic kidney disease and hemodialysis patients (6–8). Additionally, the prevalence of GERD, as assessed by endoscopy and 24-hour pH monitoring in patients with GERD-related symptoms and ESKD, has been demonstrated to be very high (81%), suggesting that upper gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with chronic kidney disease are important in predicting the presence of GERD (9). Furthermore, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) was a risk factor for the development of GERD (9,10). This association is likely due to increased intra-abdominal pressure when the abdominal cavity is filled with dialysate fluid and its effect on lower esophageal sphincter pressure.

A potential relationship between kidney disease and GERD-associated esophagitis was suggested in an autopsy series of patients with ESKD revealing a high prevalence of mild to severe esophagitis (36%) (11). However, in prospective studies of patients with chronic kidney disease on hemodialysis, the prevalence of esophagitis was much lower, ranging from 5.8% to 13% (12–14). The prevalence rate of endoscopic esophagitis in these studies is similar to or slightly greater than that in the general population. In a case-controlled study showing that the prevalence of GERD symptoms and esophagitis was increased in chronic kidney disease patients, multifactorial logistic regression analysis revealed a negative relationship between the presence Helicobacter pylori infection in the stomach and reflux esophagitis (8). This finding suggests that H. pylori infection may protect against the development reflux esophagitis which has been previously proposed by others (15,16).

A high prevalence of hiatal hernia has been reported in patients with ESKD (2,17,18). Hiatal hernias are known to play a role in the pathophysiology of GERD by altering the antireflux barrier and by acting as a reservoir for potential acid refluxate. Nonspecific esophageal motility disorders have been identified in chronic hemodialysis patients (19–21); however, the clinical significance of these findings is uncertain.

A presumptive diagnosis of GERD can be made when esophageal symptoms such as heartburn and regurgitation are present, and empiric therapy with acid-suppressive therapy with a proton pump inhibitor should be instituted. Symptom response to therapy confirms the diagnosis. Endoscopy should be performed in patients with persistent symptoms. Early endoscopy is indicated for unexplained nausea and vomiting or when alarm symptoms such as dysphagia are present.

STOMACH/DUODENUM

STOMACH/DUODENUM

Dyspeptic symptoms are very common in patients with chronic kidney disease leading to investigation for possible gastroduodenal pathology, such as gastritis, duodenitis, and peptic ulcer disease. Many decades ago, a high prevalence of diffuse hemorrhagic gastritis and duodenitis was described in patients with fatal acute uremia (22,23). A subsequent autopsy study of chronic hemodialysis patients revealed a similar frequency of gastritis, which was less extensive and severe (11). More recent radiologic and endoscopic studies have confirmed a high prevalence of gastroduodenal lesions—such as gastritis, gastric erosions, duodenitis, and duodenal erosions—in patients with chronic kidney disease with endoscopic or histologic evidence of peptic disease found in up to 60% to 74% of the patients (12,14,24–27). There is a strong association between H. pylori infection and gastritis; however, poor correlation between endoscopic and histologic findings was seen (24).

Physiologic abnormalities in the presence of ESKD—such as decreases in pancreatic and duodenal bicarbonate secretion and elevated serum gastrin levels—led to speculation of an association between chronic kidney disease and peptic ulcer disease. Early clinical studies of small numbers of patients utilizing diagnostic radiology techniques suggested that chronic kidney disease was a risk factor for the development of peptic ulcers, but more recent endoscopic studies in patients on chronic hemodialysis have found a prevalence of peptic ulcers similar to that of the general population (12,14,28). Identified risk factors for the development of peptic ulcers include age, peritoneal dialysis, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, and low serum albumin (29). There is a difference in the clinical presentation and endoscopic features of peptic ulcers in uremic patients compared with patients with normal kidney function. Uremic patients are more likely to be asymptomatic (13) or have low symptom scores (27) and to present with hemorrhage (30,31). In addition, uremic patients are more likely to have giant and multiple ulcers as well as H. pylori–negative and postbulbar duodenal ulcers (30,32).

Given the frequency of dyspepsia in patients with chronic kidney disease and the known role of H. pylori as a pathogen in the development of gastritis and peptic ulcer disease, a number of studies have addressed the prevalence of H. pylori in ESKD. Most studies have demonstrated that the prevalence of H. pylori infection in patients with ESKD is similar to or possibly less than that of the general population (33–40), and there appears to be an inverse association between the duration of dialysis treatments and the presence of H. pylori infection (38,39). Dyspepsia is not associated with H. pylori infection in patients with chronic kidney disease (26,41), a finding that is similar to the lack of a clear association between H. pylori infection and functional dyspepsia in the general population. These findings suggest that other factors likely contribute to the development of gastritis and dyspepsia.

Multiple diagnostic tests are available to detect H. pylori infection including histology, rapid urease test (RUT), H. pylori stool-specific antigen (HpSA), and [13] C-urea breath test ([13] C-UBT). Using histology as the gold standard, the diagnostic accuracy of RUT is decreased in patients on hemodialysis compared to patients with chronic kidney disease and patients with normal kidney function (27). However, the diagnostic accuracy of the noninvasive tests, [13] C-UBT and HpSA, remains high in hemodialysis patients (27,42). Standard treatment of H. pylori infection with proton pump inhibitor–based triple therapy (i.e., omeprazole, amoxicillin, clarithromycin) twice daily for 2 weeks is as effective in patients with chronic kidney disease on hemodialysis or CAPD as in those individuals with normal kidney function (43,44).

Another potential cause of frequent dyspeptic symptoms—such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal bloating, early satiety, and anorexia—in dialysis patients with chronic kidney disease is abnormal or delayed gastric emptying (41,45–48). Gastroparesis is a common complication of diabetes mellitus, the most common cause of chronic kidney disease requiring dialysis, particularly in the presence of other end-organ damage such as chronic kidney disease. In addition to diabetic gastroparesis, gastric emptying can be significantly delayed in nondiabetic dialysis patients as well (48–51). Potential causes of abnormal gastric emptying in these patients include neuropathy directly related to the uremia and alterations in gastrointestinal hormones that can affect gastric emptying. The prevalence of dysmotility-like dyspepsia has been shown to be higher in CAPD patients than in hemodialysis patients (41). In CAPD patients, studies showing delayed gastric emptying when the abdominal cavity is filled with dialysate and absent when the abdominal cavity is empty suggest that increased intra-abdominal pressure may play an important role (52); however, this remains controversial (53). Delayed gastric emptying in patients with chronic kidney disease is not associated with H. pylori infection (41,51,54).

Upper gastrointestinal symptoms due to gastroparesis may have an adverse effect on nutritional status and may be one of the important factors that lead to malnutrition in dialysis patients. Delayed gastric emptying in chronic hemodialysis patients is associated with changes in biochemical indicators of nutritional status such as albumin and prealbumin (49). Furthermore, treatment of gastroparesis in nondiabetic dialysis patients with promotility agents such as erythromycin or metoclopramide can significantly improve gastric emptying and short-term nutritional status as measured by serum albumin (50).

There are several therapeutic options for the management of patients with dyspepsia. An empiric trial of a proton pump inhibitor can be considered. Alternatively, a serum H. pylori antibody can be obtained. If the H. pylori antibody is positive, appropriate treatment with a 2-week course of proton pump inhibitor–based triple therapy should be instituted. In patients with persistent dyspepsia, endoscopy is warranted. Early endoscopy should be pursued in older patients and in those with associated vomiting, anorexia, and unexplained weight loss. When empiric therapy fails and a diagnostic esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is unrevealing, it may be useful to obtain a gastric emptying study to assess for gastroparesis that can be treated with a promotility agent such as metoclopramide.

GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

Gastrointestinal bleeding is a common complication of ESKD, accounting for up to 8% to 12% of cases of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (55,56). The frequency of bleeding in patients with chronic kidney disease with underlying gastrointestinal pathology may be partially explained by a high occurrence of clotting abnormalities in this patient population (56). These are primarily due to multifactorial platelet dysfunction, but abnormalities in clearance of anticoagulant medications in ESKD can contribute to increased risk of bleeding (57). Treatment options to restore platelet function in patients with ESKD and active bleeding include correction of anemia (58), administration of desmopressin [1-deamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin (DDAVP)] (59), and cryoprecipitate infusion (60). Most studies have found that peptic ulcer disease (gastric or duodenal ulcers) is the most common cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with chronic kidney disease, accounting for 30% to 60% of bleeding episodes (55,56,61). Risk factors for upper gastrointestinal bleeding among patients with ESKD include cardiovascular disease, current smoking, and inability to ambulate independently (62).

The association of chronic kidney disease with bleeding upper gastrointestinal angiodysplasias is controversial. A few studies have shown that angiodysplasias of the stomach and duodenum are a significantly more common source of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with chronic kidney disease (55,56,63,64), with angiodysplasias identified as the cause of bleeding in 13% to 23% of patients (55,56). However, this has not been a universal finding (61,65,66). In one study, the prevalence of angiodysplasias as a cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding was related to the duration of kidney disease and the need for dialysis (55). The lesions are often multiple and can also be found in the small bowel and colon (56,63,67,68). Recurrent bleeding is frequent and more common in patients with chronic kidney disease (56,64). In addition to acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage, patients with bleeding angiodysplasias often present with chronic gastrointestinal blood loss manifested by chronic anemia and hemoccult-positive stool (65). Erosive esophagitis and erosive gastritis may also be more common causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in chronic kidney disease patients (56,61).

The diagnosis of angiodysplasias in the appropriate clinical setting is usually made by endoscopy with upper endoscopy and/or colonoscopy. The diagnosis of angiodysplasia can sometimes be difficult to make, as the lesions may be very small and hidden between or behind folds. A high index of suspicion for the possibility of angiodysplasias should be maintained in patients with recurrent acute bleeding episodes, which are undiagnosed after conventional endoscopy with upper endoscopy and colonoscopy, and in patients with unexplained chronic iron deficiency anemia and hemoccult-positive stool. In this subset of patients, small bowel angiodysplasia is the most common cause of bleeding, and further endoscopic evaluation of the small bowel with enteroscopy and/or wireless capsule endoscopy is warranted. Chronic kidney disease is a predictive factor for positive findings on enteroscopy and wireless capsule endoscopy (69,70). When identified endoscopically, the lesions can be successfully treated with thermal therapy using contact probes (71) or argon plasma coagulation (72).

Endoscopic intervention for gastrointestinal angiodysplasias is ineffective when the vascular lesions are diffuse, inaccessible, or escape identification. Additionally, rebleeding is an important clinical issue after endoscopic therapy. Estrogen and progesterone therapy has been proposed for the prevention of recurrent bleeding from angiodysplasias. Potential mechanisms for the beneficial effect of estrogen on bleeding gastrointestinal telangiectasias include improvement in coagulation status with decreased bleeding time and improvement in the integrity of the vascular endothelial lining. Studies of hormonal therapy have had mixed results with two small studies showing cessation of bleeding and decreased transfusion requirement (68,73), but a more recent larger trial finding no significant benefit with hormonal therapy (74). Other therapies for recurrent bleeding from angiodysplasias have been studied. Treatment with thalidomide, an angiogenesis inhibitor, improved outcomes in a small study as compared to iron supplementation (75). Octreotide has been shown to benefit patients in small studies, and a decrease in transfusion requirement with octreotide treatment was confirmed in a meta-analysis (76). However, a recent systematic review found low quality or insufficient evidence to support treatment of angiodysplasia with hormonal therapy, thalidomide, or octreotide (77).

PANCREAS

PANCREAS

Abnormal glandular morphology and pancreatic exocrine function are very common in ESKD. Pancreatic endocrine function as measured by beta-cell response has been consistently shown to produce normal glucose and insulin levels which do not differ between groups of patients with ESKD regardless of dialysis modality. In contrast, C-peptide concentrations are markedly increased over controls, and the return of insulin to basal levels is delayed with ESKD (78). Several mechanisms have been postulated to explain this finding. Iron deposition from chronic administration and elevated levels of islet amyloid polypeptide may contribute to beta-cell dysfunction (79,80). Aggressive iron depletion with phlebotomy and recombinant human erythropoietin reverses some of these defects, and recently, deferoxamine therapy has shown substantial promise in reducing insulin resistance and improving B-cell function (81). L-carnitine nutritional supplements may provide additional benefit by improving some of the beta-cell responsiveness, but the clinical benefit remains to be proven (82).

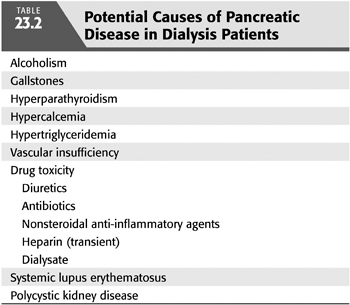

Approximately 70% of patients have abnormal pancreatic exocrine function (83). Investigators have demonstrated reduced duodenal amylase, lipase, bicarbonate, and protein levels in response to secretory stimulation tests (84,85). In addition, fecal chymotrypsin levels are significantly reduced in chronic kidney disease (86). These changes in excretory pancreatic function are infrequently associated with ultrasonographic changes within the pancreas. Autopsy studies reveal a correlation between pancreatic disease and elevated intact parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels (87). Whether these abnormalities are part of the clinical spectrum of chronic pancreatitis or represent a distinct uremic pancreatopathy is unclear. Other possible causes of pancreatic disease in dialysis patients include hypercalcemia, hypertriglyceridemia, vascular insufficiency, and drug toxicity [such as long-standing diuretic use, antibiotics, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)] (TABLE 23.2). The clinical result of these changes may lead to steatorrhea, which may contribute to the malnutrition seen commonly in dialysis patients (88).

Patients with chronic kidney disease frequently have elevated serum amylase and lipase levels in the absence of clinical pancreatitis, probably related to diminished kidney clearance. The kidney is responsible for 20% of the clearance of these enzymes. Serum amylase, lipase, and trypsin values remain normal until the creatinine clearance is less than 50 mL/min (89). The levels then rise to approximately two to three times normal, which may correlate with the duration of chronic kidney disease (90). Total serum amylase, pancreatic amylase, and salivary amylase isoenzymes are elevated, but isoenzymes are not routinely measured in clinical practice (86,91). Serum amylase in asymptomatic patients rarely exceeds 500 IU/L and is unaffected by dialysis (89,92). The predialysis serum lipase activity is also increased in patients with ESKD and rises further after hemodialysis. This effect is related to the lipolytic effect of intradialytic heparin and dose. Patients on CAPD and with peritonitis also have mild elevations in serum and peritoneal amylase (up to 100 IU/L); however, marked elevations, as seen in patients with pancreatitis or cholecystitis, are not found (93,94).

Acute pancreatitis has been reported to be more common in ESKD than in the general population. Several series report an incidence of 2.3% to 6.4% in patients with kidney disease (95,96). Pancreatitis is significantly more common in those with alcohol abuse, systemic lupus erythematosus, and polycystic kidney disease. It is not significantly associated with biliary tract disease, hyperlipidemia, or hypercalcemia. The mortality is 20% to 50%. Acute pancreatitis is equally common in patients on CAPD and on hemodialysis (96–98). The dialysate may be clear, hemorrhagic, or cloudy. It has been suggested that metabolic abnormalities related to absorption of glucose and buffer from dialysate, hypertriglyceridemia, or absorption of a toxic substance in the dialysate, bags, or tubing may increase the risk of pancreatitis in dialysis patients (99).

Chronic pancreatitis can interfere with absorption and may result in malnutrition, vitamin deficiencies, and chronic wasting in dialysis patients (88). Histologic evidence of pancreatitis can be seen in greater than 50% of patients with ESKD, 85% of which is chronic (100). Pathologic changes include calcifications, fibrosis, abscess formation, and deposition of hemosiderin. However, despite the frequency of chronic morphologic findings and functional abnormalities of the pancreas associated with ESKD, clinically significant chronic pancreatitis is rare. Most patients are asymptomatic; rarely, symptoms suggestive of malabsorption, such as steatorrhea, develop (101).

Diagnosing pancreatitis in dialysis patients can be very difficult. Dialysis patients frequently experience abdominal discomfort, nausea, and vomiting as a result of uremia or dialysis treatments. Nonspecific elevations of serum amylase and lipase are common. Therefore, interpretation of hyperamylasemia must be approached with caution. Clinicians should maintain a high level of suspicion if values exceed three times the normal limit. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) can be useful to confirm pancreatic inflammation and peripancreatic abnormalities suspicious for pancreatitis. Early diagnosis and therapy may reduce the progression or severity of disease. Acute pancreatitis is more likely to be severe and is associated with a worse prognosis in dialysis patients than in the general population (102). Using Ranson’s criteria, the mortality for patients with three or more (including kidney insufficiency) criteria approaches 70%, compared to 11% for patients without kidney disease. Complications such as pancreatic abscesses, pseudocysts, and necrosis occur with the same frequency as in the general population. However, dialysis patients develop twice as many systemic complications, such as cardiovascular and pulmonary complications, and sepsis (103). Treatment should be similar to that for nondialysis patients, including bowel rest, volume resuscitation as needed with frequent dialysis to maintain euvolemia, and pain control. Pain management strategies should avoid the use of meperidine (Demerol), which may lower the threshold for seizures in ESKD.

NEPHROGENIC ASCITES

NEPHROGENIC ASCITES

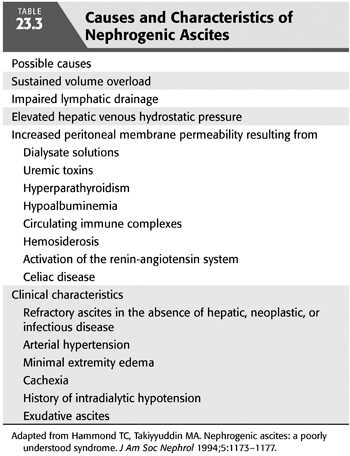

Nephrogenic ascites (NA) or idiopathic dialysis ascites (IDA) is an uncommon but important cause of morbidity in dialysis patients. By definition, it is a disorder that manifests as massive, refractory ascites in chronic hemodialysis patients where all other causes of ascites have been excluded (104). The incidence appears to be decreasing with improved volumetrically controlled dialysis and nutrition and is center-dependent (104,105). Most patients present with sustained volume overload, arterial hypertension, large interdialytic weight gains, minimal extremity edema, cachexia, and a history of dialysis-associated hypotension (104–107). NA is frequently associated with hyperparathyroidism, hypoalbuminemia, and uremia; has a male predominance; and is unrelated to age or race (108). It is associated with a grave prognosis, with a 1-year mortality rate of more than 30% (106) (TABLE 23.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree