Carol A. Kauffman

Fungal Infections of the Urinary Tract

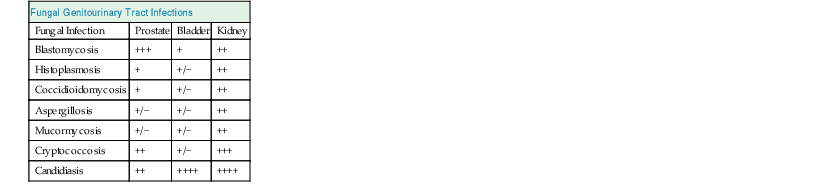

Funguria is a frequent finding in hospitalized patients. Almost always, the organisms found in urine are Candida species, although several other yeasts, and less often, molds and endemic fungi, can also be found (Table 55-1). Candiduria is not a symptom, a sign, or a disease, but frequently it is a perplexing phenomenon for the physician to address. In reality, most patients with candiduria are asymptomatic and have colonization of the bladder or of an indwelling urinary catheter. The most difficult diagnostic problem is determining when infection, rather than colonization, is present. Diagnostic tests to define whether candiduria is related to colonization or infection have not been standardized; similarly, diagnostic studies to localize the site of infection to either the bladder or the kidneys are not well established. In contrast to the situation with candiduria, growth in urine of organisms such as Blastomyces dermatitidis, Aspergillus spp., and Cryptococcus neoformans almost always reflects disseminated infection. This chapter outlines an approach to the diagnosis and treatment of candiduria and other, less common fungal urinary tract infections (UTIs).

Candida

Epidemiology

Candida species are common inhabitants of the perineum but are not found in urine in appreciable numbers in healthy hosts. However, a variety of predisposing factors allow these commensals to grow in the urine and in some cases, to invade the bladder or the upper urinary tract and cause infection. These factors are more frequently encountered in hospitalized patients, especially those in the intensive care unit (ICU).1 In a recent point prevalence survey of positive urine cultures obtained from hospitalized patients, Candida species were found in almost 10% of specimens and were the third most common microorganism isolated from urine.2

Risk factors for candiduria, but not specifically for Candida UTI, include increased age, female gender, antibiotic use, urinary drainage devices, prior surgical procedures, and diabetes mellitus3–5 (Table 55-2). In the largest surveillance study, urinary drainage devices, mostly indwelling urethral catheters, were present in 83% of patients who had candiduria.3 In a multicenter study of patients in an ICU setting, independent risk factors associated with candiduria were age over 65, female gender, diabetes mellitus, prior antibiotic use, mechanical ventilation, parenteral nutrition, and length of hospital stay before ICU admission.4 A case-controlled study that compared candiduria caused by Candida glabrata with that from Candida albicans found that C. glabrata was more common in patients with diabetes and in those who had received prior treatment with fluconazole.5 Most patients in these studies had colonization and not infection with Candida.

Table 55-2

Risk factors for candiduria.

| Risk Factors for Different Types of Candida Urinary Tract Infections | |

| Type | Risk Factors |

| Renal (hematogenous) | Neutropenia, recent surgery, central venous catheter, parenteral nutrition, antibiotics, dialysis |

| Lower urinary tract | Indwelling bladder catheter, older age, female, diabetes, obstruction, antibiotics, urinary tract instrumentation |

| Upper urinary tract | Older age, diabetes, antibiotics, obstruction, urinary tract instrumentation (e.g., nephrostomy tube, ureteral stent) |

Prospective controlled studies assessing risk factors for well-documented Candida UTI have not been performed because firm diagnostic criteria have not been established. However, clinical experience suggests that UTI is more common in diabetic patients and those with urinary tract obstruction.

Pathogenesis

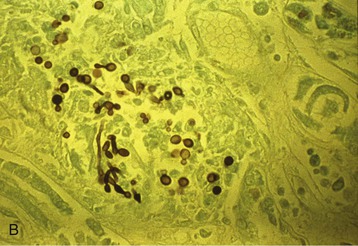

Candida tends to cause disease by either the hematogenous or the ascending route. This contrasts with most UTIs caused by bacteria, in which infection ascends from bladder to the collecting system of the kidney. The pathogenesis of hematogenous seeding of Candida to the kidney has been studied with animal models.6 Multiple microabscesses develop throughout the cortex, with the yeasts penetrating through the glomeruli into the proximal tubules, where they are shed into the urine (Fig. 55-1). Healthy animals eventually clear the infection, but immunocompromised animals do not. Consistent with the experimental studies, renal microabscesses have been identified at autopsy in most patients with invasive candidiasis. For ascending infection with Candida, obstruction is an important factor in some patients. Virulence factors of Candida, such as those that control adherence and biofilm formation, are also likely relevant, but have not been studied in the context of Candida UTI.6,7

A unique syndrome seen early after kidney transplantation is graft site candidiasis, which appears to result from contamination of the donor kidney during the harvest procedure.8 Arteritis with aneurysm formation and rupture can result from direct fungal invasion into the arterial wall. Most patients lose the graft, and mortality is high.

Microbiology

Candida albicans accounts for 50% to 70% of all Candida urinary isolates, and C. glabrata for about 20% of isolates.3 Candida tropicalis and Candida parapsilosis are less common, and other species are rarely isolated. Certain populations of patients have a predominance of C. glabrata. Older adults frequently have C. glabrata isolated from urine, but urine cultures from neonates rarely yield C. glabrata. In a prospective survey of candiduria in renal transplant recipients, C. glabrata represented 53% and C. albicans only 35% of isolates.9

It is important to know the species causing candiduria for therapeutic reasons. Resistance to fluconazole, the primary agent used for the treatment of Candida UTIs, is common among isolates of C. glabrata and in all isolates of Candida krusei. In contrast, almost all isolates of C. albicans, C. tropicalis, and C. parapsilosis are susceptible to fluconazole.

Clinical Manifestations

Most patients with candiduria are asymptomatic, and indeed, most do not have infection. A large prospective surveillance study of patients with candiduria noted that less than 5% of patients with candiduria had any symptoms suggesting UTI.3 When patients have symptomatic cystitis or pyelonephritis, symptoms are indistinguishable from those noted with bacterial infections. Cystitis is manifested by dysuria, frequency, urgency, and suprapubic discomfort; patients with upper tract infection can present with fever, chills, and flank pain. Urinary tract obstruction occurs from formation of a bezoar or fungal ball in the bladder or the collecting system.

Patients who have had seeding of the renal parenchyma during an episode of candidemia manifest the symptoms and signs associated with invasive candidiasis and not UTI. Chills, fever, hypotension, and other manifestations of sepsis are often noted in patients who are candidemic.

Diagnosis

Major diagnostic difficulties are encountered in trying to differentiate contamination of a urine specimen from colonization of the bladder or an indwelling urethral catheter from invasive infection of the bladder or the kidney.10 Contamination is most easily differentiated by simply repeating the urine culture to determine if candiduria persists. It may be necessary to obtain the second urine specimen by sterile bladder catheterization if the patient is unable to accomplish a clean-catch collection. In those patients who have an indwelling urethral catheter, the catheter should be replaced and a second urine specimen collected. For either of these circumstances, if the repeated culture yields no yeasts, no further diagnostic studies or therapeutic interventions are needed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree