Simon J. Davies, Martin E. Wilkie

Complications of Peritoneal Dialysis

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is associated with a number of potential complications that affect technique and patient survival. Understanding their etiology, presentation, and management frequently enables their prevention, correction, or amelioration. These complications can be separated into mechanical aspects relating to the PD technique and the catheter itself, infections either at the exit site of the catheter or peritonitis, changes affecting the peritoneal membrane, and metabolic consequences that arise from components of the dialysis solutions—predominantly the glucose content. Mechanical or catheter-related problems are more likely to occur at the start or early in the treatment course, or when there is an increase made to the volume of the dialysate; infectious complications can occur at any stage during the course of treatment, whereas membrane and metabolic problems are more prominent after the patient has been on treatment for months or years.

Catheter Malfunction

Optimal Timing and Placement of the Peritoneal Dialysis Catheter

Catheter dysfunction adversely affects patient outcome by preventing commencement of the chosen dialysis modality, as well as by being disruptive to training schedules and increasing health care costs. Published literature does not give a strong indication that one insertion technique is better than another, although a recent meta-analysis suggested an advantage of the laparoscopic compared with the open surgical insertion technique1 (techniques of catheter insertion are further discussed in Chapters 92 and 96). It is clear that the enthusiasm and experience of the operator are key determinants of catheter outcome,2 and international guidelines describe the optimal conditions for catheter insertion.3 Timing is also important: Patients randomized to the late start limb of the Initiating Dialysis Early and Late (IDEAL) study (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] 5 to 7 ml/min), as opposed to patients starting dialysis early (eGFR 10 to 14 ml/min), were less likely to start on PD despite it being their treatment of choice, probably because of delayed planning.4 Early catheter problems are more difficult to manage in the absence of residual kidney function. For optimized catheter function it is necessary that each center audit its success with catheter placement against internationally agreed-on standards as part of local quality improvement cycles.2,3

Catheter Function: Inflow

A 2-liter bag of dialysate should take 15 minutes or less to run into the peritoneal cavity. If inflow is significantly slowed or even stopped completely, mechanical causes should be suspected. After a check to ensure that the tubing and catheter are not kinked, that all clamps or rollers are open to the inflow position, and that any frangible seal is fully broken, the catheter should be flushed vigorously with 20 ml of heparinized saline. If the catheter is cleared, then heparin should be added (500 U/l) to the next few cycles because the cause of the blockage is often a fibrin plug. Should the catheter remain blocked, a plain abdominal radiograph is required. If this shows that the catheter is in a satisfactory position in the pelvis, an attempt to restore patency should be made with a thrombolytic agent (urokinase, 100,000 U or tissue plasminogen activator [tPA], 2 mg in 40 ml of normal saline, either instilled for at least 1 hour)5 diluted in normal saline, which can be instilled into the PD catheter for approximately 1 hour before being withdrawn. If inflow is restored, heparin should be added to the dialysate for the next few cycles. We would no longer recommend the use of an endoscopic brush because of safety concerns.

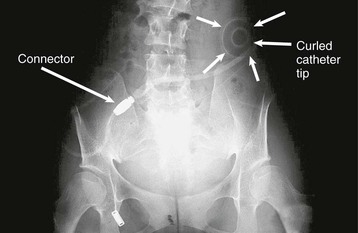

If the radiograph shows the catheter to be malpositioned, an attempt should be made to reposition the catheter tip into the pelvis (Fig. 97-1). This can be done under radiologic screening with a sterile catheter guide although this is not widely practiced. Alternatively, the catheter can be repositioned at laparotomy or with the laparoscope. Sometimes the catheter becomes wrapped in omentum, suggested usually by complete inflow and outflow failure. This requires a partial omentectomy or an omental hitch, a surgical procedure in which the omentum is temporarily held away from the catheter by a dissolvable suture. The value of laparoscopy in this context is that it can provide a diagnosis as to the cause of catheter flow failure and provide a solution—for example, by repositioning the catheter, removing an omental wrap, or performing a limited omentectomy.

Catheter Function: Outflow

The most common reason for outflow failure is constipation, although causes of inflow failure discussed previously should also be considered. Loading of the bowel with fecal material is often obvious on a plain radiograph, but treatment for constipation should be initiated without recourse to this investigation because it is so common. Constipation should be treated with oral laxatives or an enema. Subsequently, bowel action should be kept regular by increasing the fiber in the diet and, if necessary, adding a mild laxative. Slow outflow can be a problem in patients using automated peritoneal dialysis (APD), resulting in excessive machine alarms. This is can be managed by switching to tidal APD and using a relatively large residual volume, for example 25% to 50% of the fill volume.

Fibrin in the Dialysate

The mesothelial cells of the peritoneal membrane have a range of physiologic functions including the production of fibrinolytic agents such as tPA. This process is disrupted during peritonitis when the appearance of fibrin in the dialysate is common. If fibrin causes restriction of dialysate flow, heparin (500 U/l) should be added to each bag. A small number of patients have fibrin formation in the absence of peritonitis. Immediately on drainage the bag may appear cloudy, but on standing the fibrin will aggregate and the fluid becomes clear. The first time this happens, a sample must be sent to the microbiology laboratory to exclude infection. If the results of this testing prove negative, the patient can be reassured.

Fluid Leaks

Fluid leaks occur whereby dialysate leaks out of the peritoneal cavity—which can be either visible externally or not. It is recommended that after PD catheter surgery, patients be allowed to heal sufficiently before use (2 weeks) to minimize this risk. If the catheter has to be used early, then low volumes should be used (start with 1 liter) in the supine position (e.g., APD with a dry day), with the patient instructed not to mobilize while dialysate is in the peritoneal cavity during the first 2 weeks after catheter insertion. Although PD catheters can be used as the primary approach to manage late-presenting patients or for acute kidney injury, the incidence of leaks is higher under these conditions.6

External Leaks

On occasion, fluid may leak from the exit site or even the incision used to insert the catheter into the peritoneal cavity. A leak of dialysate, which is confirmed by measuring glucose concentration in the leaking fluid, is a risk factor for infection. It is important that PD catheters be adequately immobilized if used for early start PD to reduce the risk of tugging and leak.

Internal Leaks

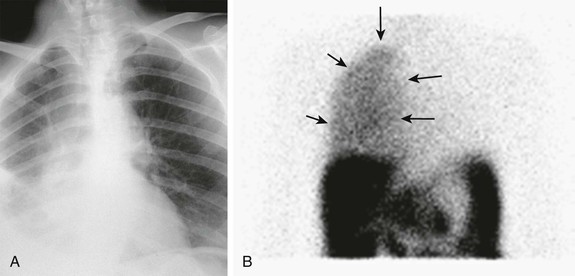

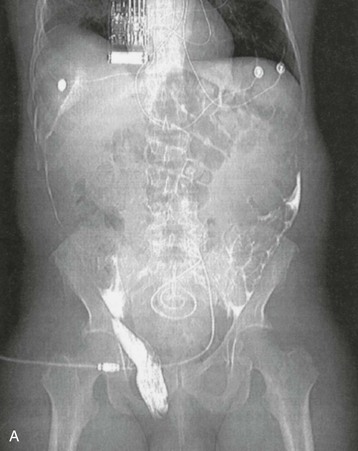

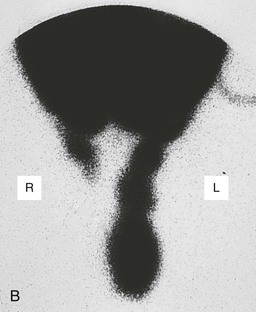

Isolated edema of the abdominal wall suggests an internal leak from the peritoneal cavity, either spontaneously or in association with a surgical hernia. In contrast, genital edema suggests an inguinal hernia or patent processus vaginalis. On occasion, both can be present. The site of the leak can be visualized on computed tomography (CT) scanning after intraperitoneal instillation of contrast material or on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without the use of contrast. It may be necessary for the patient to stand or to perform other maneuvers to increase intra-abdominal pressure before the leak is demonstrated (Fig. 97-2, A). An alternative diagnostic test is to perform scintigraphy after injection of a compound such as technetium Tc 99m–labeled diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (99mTc-DTPA; Fig. 97-2, B). A surgical repair will be required if a major leak is visualized and should always be considered when there is a hernia. Most leaks, however, will heal after resting or with APD, using dry days, or temporary HD.

Hydrothorax

A pleural effusion can occur with generalized fluid overload or local lung disease, but it is occasionally caused by a leakage of dialysate through the diaphragm (Fig. 97-3, A). This occurs more commonly on the right side. A leak is most simply indicated by aspirating a sample of the effusion and demonstrating that its glucose concentration is higher than the patient’s blood glucose concentration, and this can be confirmed by scintigraphy after intraperitoneal instillation of isotope, usually 99mTc-DTPA (Fig. 97-3, B). If one can be confident that the pleural effusion is not caused by the PD, then PD can be continued while the effusion is investigated and managed. Although there are reports that repairing pleural leaks allows subsequent PD, the best advice is to transfer the patient to HD unless there are very strong reasons not to.

Pain Related To Peritoneal Dialysis

Inflow Pain

Soon after starting PD, patients may experience pain during fluid inflow, and occasionally pain affects the shoulders and is pleuritic in nature, possibly because of diaphragmatic irritation, which usually resolves over the following days. Slowing the rate of fluid inflow will often reduce the symptoms, and peritonitis should be excluded and treated. A small number of individuals have persistent inflow pain, and the use of bicarbonate-lactate–buffered dialysate at physiologic pH improves symptoms in such patients.7

Outflow Pain

Some patients have discomfort or even pain when the fluid is drained out, which can be experienced in the genital area or rectum, and is commonly a result of pelvic irritation related to the catheter tip. This emptying sensation is abolished when the next cycle runs in and is best treated by leaving a small residual volume of fluid in the peritoneal cavity at the end of the drain, for example by using tidal APD.

Blood-Stained Dialysate

Blood-stained dialysate is uncommon. It is rarely serious but causes considerable alarm to the patient. There is sometimes a clear history of trauma to the abdomen or of unexpected strain. A range of rare conditions are associated with this complication8; a few female patients relate the episode to their time of ovulation or menstruation. The treatment is to flush the abdomen with a few cycles of dialysate containing heparin (500 U/l) to minimize the chances of clotting in the catheter. The problem usually resolves spontaneously and often is visible only in one outflow. It is unusual for the blood-stained dialysate to be associated with infection, although it is wise to have the fluid cultured. Routine use of antibiotics is not necessary.

Infectious Complications

Peritonitis

There are wide variations in peritonitis rates both between and within countries. Reducing peritonitis rates requires a multifaceted, multidisciplinary approach based on the use of preventative measures around the time of catheter insertion, the use of modern disconnect systems, exit site management, and education of patients and health care professionals.9 This should be supported by regular local audit of peritonitis rates including causative organisms and local sensitivities, which is increasingly important because of the emergence of resistant organisms, and the requirement to use antibiotics effectively. Root cause analysis should be performed after each episode of PD peritonitis, with retraining as appropriate. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of PD peritonitis are published by the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD; www.ispd.org).10 The spectrum of peritonitis and its management in children have also recently been described in detail.11 The reader is directed to a detailed review on reducing peritonitis risk.9

Diagnosis of Peritonitis

The diagnosis of peritonitis should be suspected in any patient who develops a cloudy bag when PD fluid is drained or abdominal pain. Fever may also be present but is not a universal feature. Patients should be advised to contact their dialysis unit immediately if they observe a cloudy bag or develop persistent abdominal pain. Samples of the dialysate should be taken for cell count and microbiologic examination. The diagnosis is confirmed by finding more than 100 white blood cells/mm3 (1 × 107 cells/l). A Gram stain of the spun deposit should also be performed to help identify the type of causative organism, although initial treatment will usually be empiric pending culture and sensitivity results. Various culture techniques have been proposed, but white cell lysis and inoculation into blood culture media is often helpful in increasing the yield of a positive growth.

The dialysate leukocyte count will be affected by dwell length, and this needs to be taken into account in APD patients. In short dwells, the count will be lower, and under these circumstances, if the proportion of cells that are neutrophils exceeds 50%, empiric treatment of peritonitis should be commenced. Conversely, if the patient has had a dry abdomen during the day, the initial drain on connection may be cloudy. This will clear within one or two cycles, and the majority of the cells found will be mononuclear leukocytes.

Treatment of Peritonitis

The empiric treatment of peritonitis will vary according to center and should be developed in close collaboration with the local microbiology service, taking into account sensitivity patterns and infection control policy. Initial regimens must cover both gram-positive and gram-negative organisms; the latest ISPD guidelines (www.ispd.org) give examples of appropriate antibiotics including vancomycin, cephalosporins, and aminoglycosides.10,11 Dosage regimens will depend on whether the patient is on CAPD or APD. For CAPD, the antibiotic is administered as a loading dose in the first bag and then as a maintenance dose in subsequent bags. Although it was customary to transfer APD patients to CAPD for the purpose of treating peritonitis, this is no longer necessary. APD patients are now given large loading doses in dialysis fluid with a minimum 6-hour dwell (e.g., vancomycin 30 mg/kg) and then are given additional doses every 3 to 5 days according to checked blood levels. Once the culture result is available, the regimen should be modified accordingly (Table 97-1). If the organism is methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin will be continued as part of the regimen.

Table 97-1

Antibiotic regimens for bacterial PD peritonitis.

Suggested antibiotic regimens when dialysate fluid culture is available. Except for culture-negative episodes, empiric treatment is stopped once the sensitivities are known. All antibiotic regimens should be developed in consultation with local microbiology practices.

| Antibiotic Regimens for Bacterial PD Peritonitis | |

| Culture | Antibiotic |

| Enterococci (including vancomycin-resistant enterococci) | Ampicillin |

Staphylococcus aureus

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |