and pelvic inflammatory disease that lead to loss of surgical planes. Tissue trauma, electrocautery, infection, smoking, radiation, and diabetes contribute to local tissue breakdown and poor wound healing. Wound healing has four phases: coagulation, inflammation, fibroplasia, and remodeling. During the fibroplasia phase the rate of formation of fibroplastic collagen peaks at day 7 and formation continues for 2 to 3 weeks. It is this time period during which tissue breakdown is most likely to occur. Inadvertent suture in the bladder may contribute to poor healing, but Meeks (9) suggests that a suture in the bladder is not associated with fistula formation. Seventy percent to 80% of bladder injuries during gynecologic surgery go unrecognized (10). Radiation fistulas occur with endarteritis and tissue ischemia with necrosis and fibrosis. These radiation-induced lesions may present months to years after treatment (11). Minimizing the risk of injury at the time of surgery is the goal of the surgeon (Table 17.1).

TABLE 17.1 Surgical Techniques for Minimizing Lower Urinary Tract Injuries During Gynecologic Surgery | |

|---|---|

|

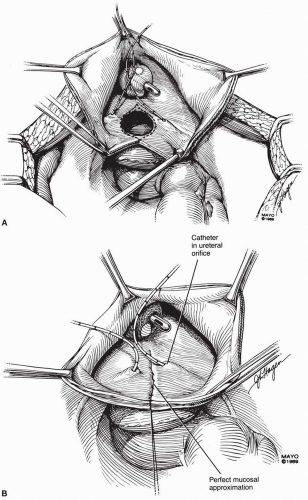

pyelography should be performed, but especially if there is a suspicion of a compound fistula including the bladder and ureter. Cystoscopy is indicated to view the bladder site of a vesicovaginal fistula and proximity to the ureters. If there has been ureteral compromise, cystoscopy with intravenous indigo carmine and retrograde studies may also be performed. Contrast cystography can also be used as a diagnostic test; however, it is not as sensitive and has a higher false-negative rate than other tests.

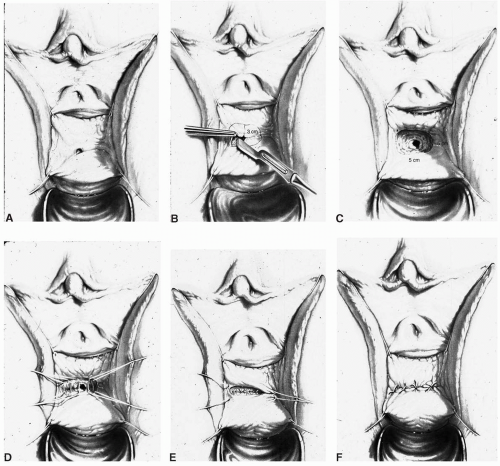

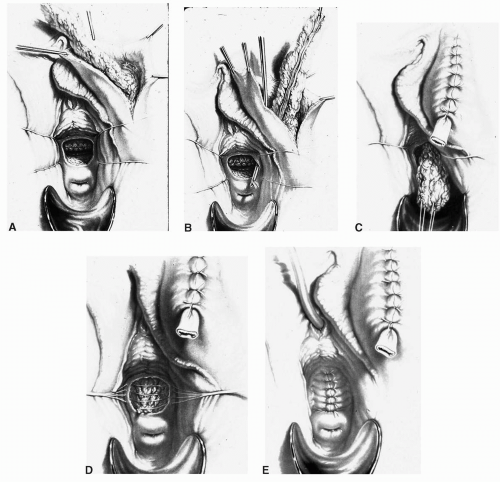

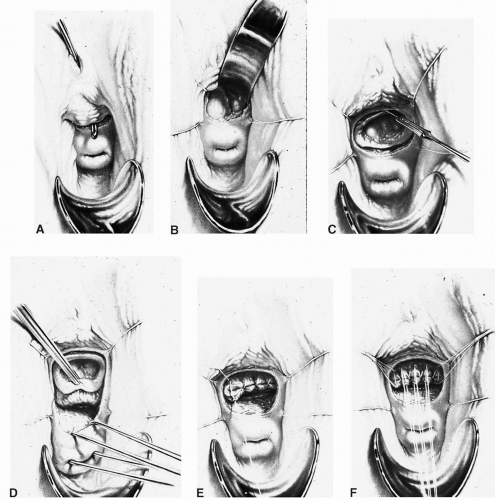

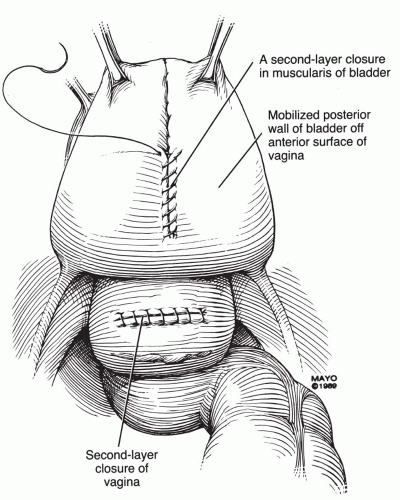

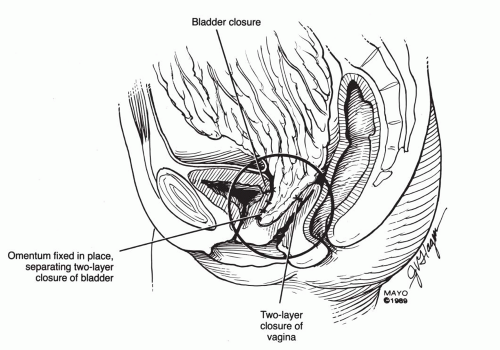

scissors) are helpful in the dissection. The vaginal epithelium is mobilized from the underlying fibromuscularis, and the fistula is excised. The margins of the defect in the bladder mucosa and muscularis are identified and closed without tension. The bladder is closed with 3-0 or 4-0 polyglactin sutures in two layers. Pubocervical fibromuscularis is then used to interpose between the bladder and vaginal mucosa. The vaginal mucosa is closed in similar fashion with the same suture. A Martius flap should be considered in cases where the risk of breakdown is relatively high. Bladder drainage postoperatively is as described above.

Ureteral catheters are placed if needed. The fistula is excised and the bladder muscle is dissected off the anterior vaginal wall, separating both structures. The bladder and vaginal defects are closed in nonopposing fashion using 3-0 or 4-0 polyglactin sutures. This approach may be hampered by limited surgical access to the fistula site.

the track has also been described (16), but deep fulguration will more likely devitalize tissue and complicate future closure. It may be reasonable to attempt these techniques in very small fistulas.

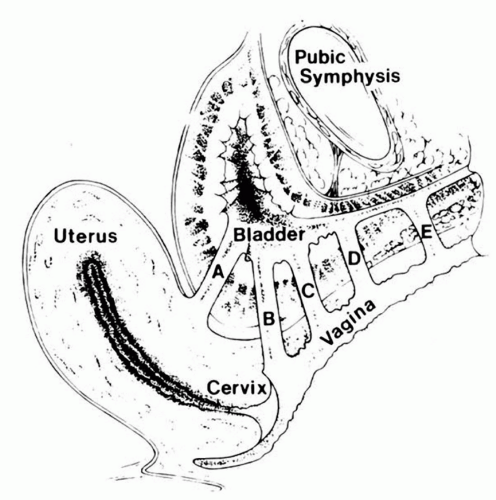

FIGURE 17.8 ● Obstetrical fistula by classification. (From Elkins TE. Surgery for the obstetric vesicovaginal fistula: a review of 100 operations in 82 patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994;170(4): 1108-1120, with permission.) (A) Vesicocervical fistula. (B) Juxtacervical fistula. (C) Midvaginal vesicovaginal fistula. (D) Suburethral vesicovaginal fistula. (E) Urethrovaginal fistula. |

FIGURE 17.9 ● Patient with total circumferential loss of entire urethra. Note the catheter inserted into the bladder at the bladder neck, but no remaining urethra remains except fragments. |

TABLE 17.2 Classification of Obstetric Vesicovaginal Fistula According to Waaldijk | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

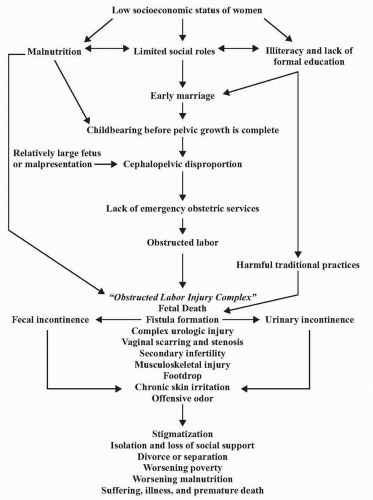

urine leakage. Nutritional build-up prior to surgery should commence in the weeks before surgery, with nutritional supplements (rich in protein, vitamins, and iron) and in some cases blood transfusion. They must also increase their hydration, as this will be important in their surgical care (23).

TABLE 17.3 Wheeless Classification of Obstetric Vesicovaginal Fistula | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree