Posterior Support Defects

Joan L. Blomquist

Geoffrey W. Cundiff

In an integrated health care program serving 149,544 women, Olsen et al noted an 11.1% lifetime risk of surgery for pelvic organ prolapse or urinary incontinence (1). Forty percent of these operations included repairs to the posterior compartment of the vagina. Importantly, the reoperation rate in this cohort was 29.9%, suggesting that our surgical interventions are not always optimal. With regard to posterior support defects in particular, there are a number of different surgical approaches currently in use. Unfortunately, there are no direct comparisons to determine if one repair is superior overall.

Posterior support defects include rectoceles, enteroceles, and perineal descent. A rectocele is a herniation of the anterior rectal wall protruding into the vaginal lumen, causing a bulge in the posterior vaginal wall. Enterocele refers to a herniation of bowel and the lining of the peritoneal cavity through the cul-de-sac of Douglas. Anatomically, this correlates with a separation of the anterior and/or posterior fascia from the uterosacral ligaments such that the vaginal epithelium and peritoneum come into direct contact. As such, an enterocele may be an apical or posterior compartment defect. Perineal descent refers to increased downward mobility of the perineal body, which usually lies within 2 cm of an imaginary line between the ischial tuberosities (2). Evaluation and treatment of posterior compartment defects should consider all three conditions.

Symptoms commonly attributed to posterior pelvic organ prolapse include herniation symptoms (bulge and pelvic heaviness), defecatory dysfunction (rectal emptying difficulties, straining at defecation, manually assisted defecation), and sexual dysfunction. One must consider the differential diagnosis of defecatory dysfunction and sexual dysfunction when determining if the surgical repair will alleviate symptoms. Studies on posterior compartment defect repairs should evaluate the effect on defecatory and sexual dysfunction in addition to anatomic outcomes. This information is imperative for proper counseling of patients.

As described in Chapter 27, treatment options include expectant management, use of a pessary, or surgical intervention. Although this chapter focuses on surgical repairs, it is important to remember that nonsurgical management should be made an option for all women. Surgical repairs to be reviewed include posterior colporrhaphy, defect-directed repair, transanal repair, posterior fascial replacement, and abdominal approaches.

ANATOMY

Although described in detail elsewhere, a brief review of anatomy is imperative before discussing the various surgical repairs. An understanding of the anatomy brings attention to the fact that there are different kinds of rectoceles for which individualized treatment may be necessary. Vaginal support arises from interactions between the pelvic musculature and connective tissue. DeLancey’s work emphasized the importance of this relationship (3). Loss of muscular support via damage or denervation puts all the pressure on the connective tissue. Connective tissue response to constant pressure is attenuation or tearing.

Muscular support results from the pelvic diaphragm, a group of paired muscles including the levator ani and coccygeus muscles. The connective tissue layer is known as the endopelvic fascia, Denonvillier’s fascia, rectovaginal fascia, or rectovaginal septum. This layer is actually a fibromuscular tissue layer, which includes fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, elastin, and type II collagen. For the remainder of this chapter, we will refer to this layer as the rectovaginal septum.

Superiorly, the rectovaginal septum attaches to the cervix and cardinal/uterosacral ligament complex.

Laterally it attaches to the pelvic sidewall (Fig. 30.1) via the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis and arcus tendineus fascia rectovaginalis (4). Inferiorly, the rectovaginal septum fuses with the perineal body (DeLancey level III). The lateral attachment (DeLancey level II) prevents ventral movement of the posterior vaginal wall. Through its attachment to the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments, the rectovaginal septum stabilizes the perineal body. Due to the support of the rectovaginal septum and pelvic diaphragm, there is limited downward mobility of the perineal body, which normally lies within 2 cm of an imaginary line between the ischial tuberosities.

Laterally it attaches to the pelvic sidewall (Fig. 30.1) via the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis and arcus tendineus fascia rectovaginalis (4). Inferiorly, the rectovaginal septum fuses with the perineal body (DeLancey level III). The lateral attachment (DeLancey level II) prevents ventral movement of the posterior vaginal wall. Through its attachment to the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments, the rectovaginal septum stabilizes the perineal body. Due to the support of the rectovaginal septum and pelvic diaphragm, there is limited downward mobility of the perineal body, which normally lies within 2 cm of an imaginary line between the ischial tuberosities.

Through his work on cadavers, Richardson hypothesized that most rectoceles were the result of discrete tears in the rectovaginal septum (5). Surgically tears have been shown to occur within the rectovaginal septum itself as well as at the lateral, superior, and inferior attachments (6). Perineal descent results from detachment of the rectovaginal septum from the perineal body. This was first described by Parks et al in 1966 (7). Since then, others have shown an association between perineal descent and defecatory dysfunction, including constipation, incomplete emptying, tenesmus, and the need to splint or use digital manipulation for defecation.

POSTERIOR COLPORRHAPHY

Posterior colporrhaphy was first described in the early 19th century. The procedure was originally designed to deal with obstetrical perineal tears by narrowing the caliber of the vagina, creating a perineal shelf, and partially closing the genital hiatus (8). A tight perineorrhaphy was also used to improve the patient’s ability to hold a pessary in place and was thought to prevent the progressions of upper genital prolapse. The original description included plication of the pubococcygeus muscles and posterior vaginal wall (colporrhaphy) and reconstruction of the perineal body (perineorrhaphy). Although developed without any real understanding of uterine and vaginal supports, transvaginal colporrhaphies have been the most commonly used surgical procedure for rectocele repair among gynecologic surgeons for over 100 years.

FIGURE 30.1 ● Oblique view of the anatomy of the rectovaginal septum’s attachments to the perineal body and pelvic side wall. In its distal half the lateral rectovaginal septum attaches to the inner (superior) surface of the levator ani muscles, while it coalesces with the fascial layer of the anterior vaginal wall at the tendinous arch of the pelvic fascia in its upper half. (From Cundiff GW, Fenner D. The management of rectocele and defecatory dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol 2004;104(6):1403-1421. Courtesy of Lianne Sullivan.) |

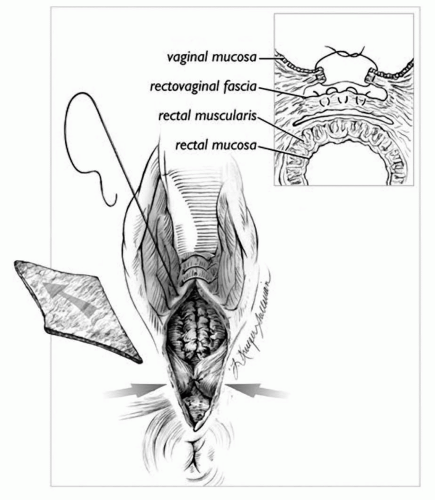

A posterior colporrhaphy begins with a perineal skin incision (Fig. 30.2). The perineal incision may be horizontal, triangular, or diamond-shaped, depending on the degree of perineal relaxation present. If the introitus needs to be narrowed with a perineorrhaphy, a triangular or diamond-shaped incision is made. The posterior vaginal epithelium is then opened in the midline to the apex of the vagina or to the cephalad border of the rectocele. The rectovaginal septum is then carefully dissected off the vaginal epithelium and plicated in the midline with continuous or interrupted delayed absorbable sutures. Some authors advocate a more aggressive plication of the levator ani muscles in the midline as well. Excess vaginal epithelium is trimmed and the vaginal epithelium is closed with a running or interrupted absorbable suture. If a perineorrhaphy is to be performed, the superficial perineal muscles and the bulbocavernosus muscles are brought to the midline using fine absorbable suture. The perineal epithelium is then closed with a subcuticular absorbable suture.

Despite its long history, the anatomic and functional success of posterior colporrhaphy was not studied until recently. Table 30.1 summarizes the recent literature on posterior colporrhaphy with and without levator plications. Anatomic cure rates range from 76% to 96% whether levator plication is performed or not. Functional outcomes have

more variable results. Kahn and Stanton (14) reported on a large retrospective series of 171 patients who underwent posterior colporrhaphy with levator plication. Constipation increased from 22% preoperatively to 33% postoperatively and fecal incontinence increased from 4% preoperatively to 11% postoperatively. In the only prospective study addressing functional outcome, Maher et al (9) reported a decrease in constipation from 76% preoperatively to 24% postoperatively.

more variable results. Kahn and Stanton (14) reported on a large retrospective series of 171 patients who underwent posterior colporrhaphy with levator plication. Constipation increased from 22% preoperatively to 33% postoperatively and fecal incontinence increased from 4% preoperatively to 11% postoperatively. In the only prospective study addressing functional outcome, Maher et al (9) reported a decrease in constipation from 76% preoperatively to 24% postoperatively.

FIGURE 30.2 ● Surgical view of the posterior colporrhaphy. A diamond-shaped piece of skin overlying the perineum is removed. The rectovaginal septum is plicated as shown in the oblique view in the inset. The trimmed skin edges are then reapproximated. (From Cundiff GW, Fenner D. The management of rectocele and defecatory dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol 2004;104(6):1403-1421. Courtesy of Lianne Sullivan.) |

Francis and Jeffcoate first described an association between dyspareunia and posterior repair in 1961 (15). Recent studies report de novo dyspareunia rates between 8% and 26%. Although thought to be related to levator plication, de novo dyspareunia occurs in posterior colporrhaphy without levator plication as well. Weber et al (10) prospectively followed 81 women with pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence before and after surgery for sexual function and vaginal anatomy. Dyspareunia occurred in 14 (25%) women after posterior colporrhaphy (p = 0.01) and in 8 (38%) of 21 women who had Burch colposuspension and posterior colporrhaphy performed together (p = 0.01). The postoperative introital caliber was not different when comparing the women with and without dyspareunia.

In summary, the traditional transvaginal colpoperineorrhaphy provides good anatomic support with potential relief of functional symptoms and a high rate of de novo dyspareunia.

DEFECT-DIRECTED REPAIR

The defect-directed repair is based on the work of Richardson. As mentioned above, Richardson hypothesized that most rectoceles are the result of discrete tears in the rectovaginal septum. These tears may occur in the fascia itself or at the superior, lateral, or inferior attachment sites. The defect-directed repair aims to fix rectoceles by identifying and closing these discrete tears. By restoring normal anatomy, advocates suggest that the defect-directed method may offer the advantage of better functional outcomes and less dyspareunia.

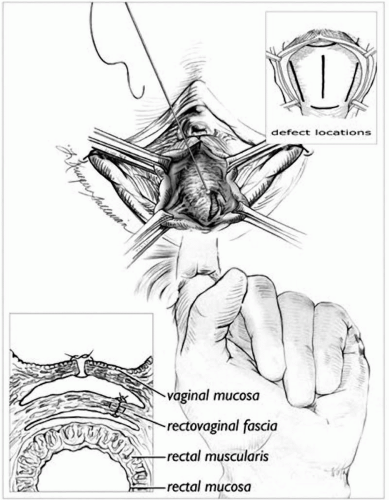

The posterior vaginal epithelium is opened in the midline and the epithelium is separated from the underlying rectovaginal septum as described in the posterior colporrhaphy section (Fig. 30.3). A finger from the surgeon’s nondominant hand is placed in the rectum, allowing identification of the fascial defects. The defects are repaired with interrupted delayed absorbable sutures. Perineorrhaphy is performed as needed. The vaginal epithelium is closed so as not to constrict the vagina.

Table 30.2 summarizes the available data on defect-directed repairs. Several retrospective reviews

have shown anatomic cure rates of 82% to 100% with improvement in dyspareunia. Cundiff et al (16) reported on 69 women who underwent the defect-directed repair over a 3-year time period. They showed improvement in constipation, difficult evacuation, fecal incontinence, and dyspareunia while maintaining an 82% cure rate. Kenton et al (18) showed a similar cure rate and improvement in dyspareunia, but only about 50% of patients with constipation and difficult evacuation improved.

have shown anatomic cure rates of 82% to 100% with improvement in dyspareunia. Cundiff et al (16) reported on 69 women who underwent the defect-directed repair over a 3-year time period. They showed improvement in constipation, difficult evacuation, fecal incontinence, and dyspareunia while maintaining an 82% cure rate. Kenton et al (18) showed a similar cure rate and improvement in dyspareunia, but only about 50% of patients with constipation and difficult evacuation improved.

TABLE 30.1 Posterior Colporrhaphy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Abramov et al (21) published the first comparative study between traditional colporrhaphy and defect-directed repair. In this retrospective study, 124 patients underwent defect-directed repair and 183 patients underwent standard posterior colporrhaphy without levator plication. The procedures were not randomized as the choice of procedure was based on the operative findings—that is, if discrete defects were found, a defect-directed repair was performed, and if no discrete defects were found, a traditional posterior colporrhaphy was performed. Rates of recurrence of rectocele beyond the midvaginal plane (33% vs. 14%, p = 0.001) and beyond the hymenal ring (11% vs. 4%, p = 0.02) and recurrence of a symptomatic bulge (11% vs. 4%, p = 0.02) were significantly higher after the site-specific rectocele repair. Rates of postoperative dyspareunia, constipation, and fecal incontinence were not significantly different between the two groups. The authors comment on the fact that the patients were not randomly assigned to the surgical procedure, so selection bias may affect the results. Paraiso et al presented the first prospective randomized trial in 2006 (22). Anatomic failure was noted in 13.5% of the site-specific group and 9% of the posterior colporrhaphy group. There was no difference between groups in functional outcome or dyspareunia.

In summary, studies to date on the defect-directed repair show low dyspareunia rates with good

functional and anatomic results. Larger prospective randomized trials between traditional colporrhaphy and defect-directed repairs are needed to further assess the question of anatomic cure and durability of the repairs.

functional and anatomic results. Larger prospective randomized trials between traditional colporrhaphy and defect-directed repairs are needed to further assess the question of anatomic cure and durability of the repairs.

FIGURE 30.3 ● Surgical view showing the defect-directed rectocele repair. The upper inset (cross-section) delineates surgical layers, while the lower inset demonstrates the potential locations for tears in the rectovaginal septum. (From Cundiff GW, Fenner D. The management of rectocele and defecatory dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol 2004;104(6): 1403-1421. Courtesy of Lianne Sullivan.) |

TRANSANAL REPAIR

Transanal repair of a rectocele was first advocated by Marks, a colorectal surgeon, in the 1960s (23). He noted that many women had continued difficulties with rectal evacuation after transvaginal rectocele repair. He also noted that many women diagnosed with a rectocele had thinning of the anterior rectal wall and an enlarged rectal ampulla. The aim of the procedure is to remove or plicate the redundant rectal mucosa and plicate the anterior rectal wall musculature.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree