present with progressively worsening symptoms of constipation and abdominal distention caused by segmental megacolon secondary to enteric neuronal degeneration. Nongastrointestinal neoplasms, such as carcinoid tumors and small cell carcinoma of the lung, have been associated with paraneoplastic visceral neuropathy, which can result in chronic constipation. The pathogenesis of this disorder is not entirely clear but may be related to either myenteric plexus inflammation or neuronal degeneration.

TABLE 23.1 Differential Diagnosis of Constipation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

of incomplete emptying. In one study, only one third of patients complaining of constipation related this complaint to infrequent defecation. More common complaints included the inability to defecate when desired (34%), the passage of hard stools (44%), and straining associated with defecation (52%) (10). Given the range of symptoms related to constipation as well as the subjectivity of self-reporting, attempts have been made over the years to classify bowel dysfunction in terms of functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) that are identified only by symptoms. To this end, the recently revised Rome III criteria are proposed to classify the functional bowel disorders, including functional diarrhea. The FGIDs will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

TABLE 23.2 Drugs Associated with Constipation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

factors to characterize subtypes of idiopathic constipation (21).

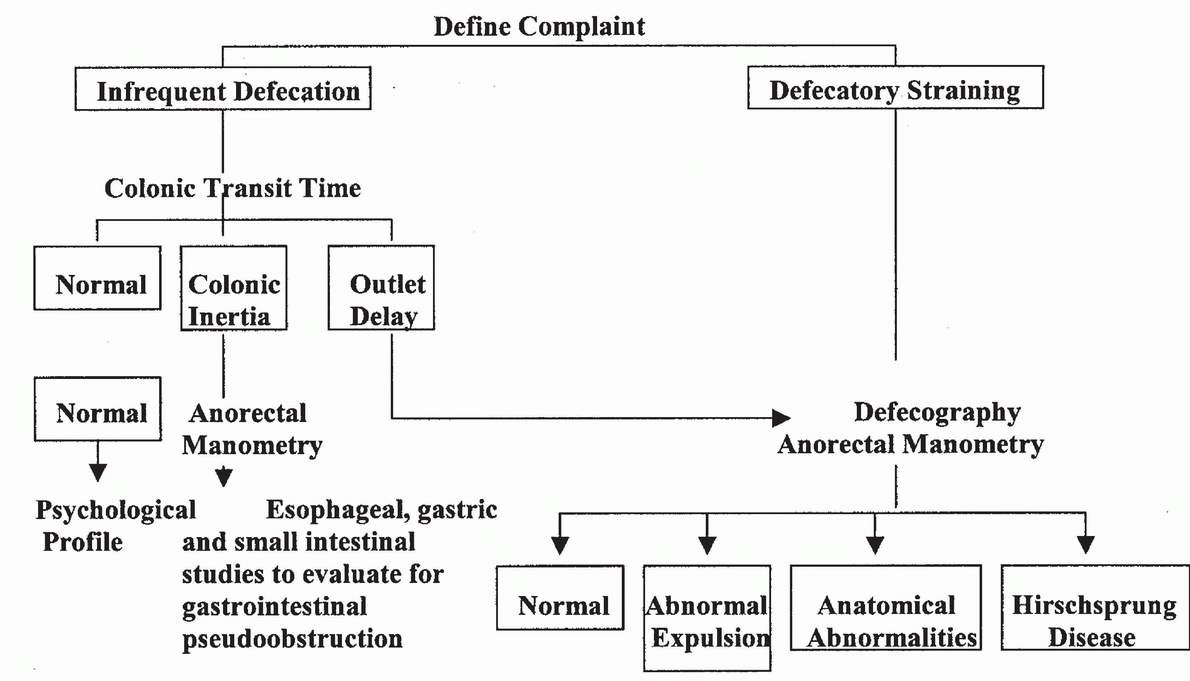

TABLE 23.3 Diagnostic Algorithm for Idiopathic Constipation | |

|---|---|

|

an underlying congenital etiology. In contrast, constipation occurring later in life tends to be an acquired disorder. A sudden or recent change in bowel habits suggests an underlying organic lesion, whereas chronic symptoms usually represent a functional bowel disorder. A review of symptoms with respect to defecatory dysfunction must include questions regarding frequency and consistency of bowel movements, the presence of melena or hematochezia, the time required for a bowel movement, and the need to strain or digitally facilitate evacuation. Associated symptoms of dyschezia, obstipation, encopresis, incomplete defecation, anismus, fecal incontinence, abdominopelvic pain, or bloating must also be reviewed.

prevent impaction are often used with children as well as with patients suffering from dementia, physical handicaps, and neurogenic constipation. Postprandial colonic motility can be enhanced, with behavior modification aimed at encouraging morning and postprandial defecation. Other initial recommendations include reducing excessive use of laxatives or cathartics, increasing daily fluid and fiber intake, and behavioral modification, including daily exercise. Biofeedback using visible or audible signal recordings from rectal manometric or electromyographic monitoring may be useful in treating chronic constipation related to pelvic floor dyssynergia (25).

over weeks. If bloating persists, a different type of fiber supplement or type of cereal may be substituted.

TABLE 23.4 Fiber Content | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 23.5 Laxatives: Mechanism of Action and Content | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

times, and stool weights (7). Mineral oil, administered orally or rectally as an enema, also works as an emollient to penetrate and soften stool.

IBS

Functional abdominal bloating

Functional constipation

Functional diarrhea

Unspecified functional bowel disorders

TABLE 23.6 Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Fewer than three bowel movements per week

Greater than three bowel movements per day

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree