Kathleen C. Kobashi, MD

Definition and Impact of Pelvic Floor Disorders

Pelvic floor disorders (PFDs), which include urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, and pelvic organ prolapse (POP), pose a prevalent worldwide health concern. (For the purposes of this chapter, “incontinence” will refer to urinary leakage unless otherwise specified.) On the basis of 2001-2004 data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), an overall prevalence of incontinence of 49.6% in 4229 women older than age 20 was reported. Of those who reported incontinence, 49.8%, 15.9%, and 34.3% reported pure stress urinary incontinence (SUI), pure urgency incontinence (UI), and mixed incontinence, respectively (Dooley et al, 2008). Interestingly, there appears to be a racial disparity with regard to pure SUI and pure UI with the odds of pure SUI being at least 2.5-fold higher in white and Mexican-American women than black women (Dooley et al, 2008; Fenner et al, 2008). The NHANES data from 2004-2005 showed that 23.7% of 1961 women described at least one PFD, and the proportion of women who reported a PFD increased with increasing age and body mass index (BMI) (Nygaard et al, 2008).

The overall prevalence of incontinence in community-dwelling men is 17% and varies with age, race, and socioeconomic status (Abrams et al, 2005; Anger et al, 2006). NHANES data revealed an 11% prevalence in those aged 60 to 64 and 31% in men 85 years or older. Daily incontinence occurs in 42% and weekly incontinence in 24%, with only 22% of those who leaked weekly seeking medical care for the problem (Harris et al, 2007). Unlike in women, there is a prevalence of urgency incontinence (40% to 80%) as compared with mixed incontinence (10% to 30%) or pure SUI (<10%) in men. Overall prevalence is higher in African-American men (21%) than in white men (16%).

Risk factors for development of POP include advanced age, increased parity (vaginal childbirth), genetic predisposition (Twiss et al, 2007), estrogen deficiency, compromised pelvic floor muscle strength, and smoking (Miedel et al, 2009; Samuelsson et al, 2000). Interestingly, recent studies indicate that current or past use of exogenous hormones in the form of oral contraception or hormone replacement therapy may paradoxically serve as a risk factor for the development of urinary incontinence (Samuelsson et al, 2000; Townsend et al, 2009). In men, comorbidities, poor general health, cognitive impairment, stroke, radiation, urinary tract infections, prostate diseases, and diabetes are all associated with incontinence (Shamliyan et al, 2009).

One questionnaire study of 4103 women, conducted in a large managed health care plan, found the prevalence of POP to be 6% (Lawrence et al, 2008). This and other studies have evaluated and found a high co-occurrence of PFDs. Lawrence and colleagues (2008) reported a co-occurrence of at least one additional PFD in approximately 80% of women with SUI or overactive bladder (OAB), 69% of women with POP, and 48% of women with anal incontinence. On the basis of the 2005-2006 NHANES data, Nygaard and colleagues (2008) found that the weighted prevalence of at least one PFD was 23.7%, increasing incrementally with age and parity. Although the prevalence of at least one PFD was 9.7% and 49.7% in women between ages 20 and 39 and those aged 80 or older, respectively, the prevalence was 12.8%, 18.4%, 24.6%, and 32.4% for those who had zero, one, two, and three or more deliveries, respectively. De Boer and colleagues (2010) reported a higher prevalence of OAB in patients with POP than in those without POP, although there was no relationship noted to exist between the grade and stage of POP and the presence of OAB symptoms. Wu and colleagues (2009) used U.S. Census Bureau population projections to forecast the change in PFD prevalence in women between 2010 and 2050. The current estimate of 28.1 million women with at least one PFD in 2010 is projected to increase substantially to 43.8 million in 2050.

The impact of PFDs is far-reaching, carrying a significant potential to affect patient quality of life (QoL), notwithstanding the psychologic burden it produces. Additionally, incontinence creates a tremendous cost to the individual and to society. Hu and colleagues (2004) estimated that the evaluation and management of incontinence and productivity lost due to the condition resulted in a $19.5 billion (year 2000 dollars) cost to society, although sensitivity analysis suggested a potential cost range of between $9.32 and $28 billion. Contemporary numbers might predictably be higher in 2009, although Hu’s most recent analysis demonstrated a 26% cost decrease compared with the 1995 report, which estimated $26.29 billion. The decrease was speculated to be due to various factors including decreased hospital stays and adjusted methods of assessing nursing home stays, routine care product use, and prevalence data. Other reports have demonstrated that medical expenditures for incontinence in the female Medicare population nearly doubled between 1992 and 1998, due primarily to increased outpatient expenditure from 9.1% to 27.3% of total Medicare costs in approximately the same time frame (Thom et al, 2005; Anger et al, 2006).

Diagnostic Evaluation

General Considerations

The type of incontinence affecting an individual must be defined and quantified in order to guide proper treatment planning. Transient or unrelated conditions that can cause leakage should be identified before proceeding with definitive therapy. Table 64–1 contains a mnemonic of transient causes of incontinence (Resnick, 1984). Table 64–2 lists current International Continence Society (ICS) nomenclature and definitions for types of incontinence (Abrams et al, 2002, 2009b). The terminology continues to adjust to reflect the evolving understanding of the condition. The importance of this flexibility has been realized and acknowledged by leaders in the subspecialty of pelvic floor medicine (Chapple, 2009).

Table 64–1 Causes of Transient Incontinence (DIAPPERS)

From Resnick NM. Urinary incontinence in the elderly. Med Grand Rounds 1984;3:281–90.

Table 64–2 Standard International Continence Society Terminology of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Pertaining to Continence

| TERMINOLOGY | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Urinary incontinence | The complaint of any involuntary leakage of urine |

| Enuresis | Any involuntary loss of urine (should be specified if it is nocturnal) |

| Urgency | The complaint of a sudden compelling desire to pass urine that is difficult to defer |

| Urgency incontinence | The complaint of involuntary leakage accompanied by or immediately preceded by urgency |

| Stress urinary incontinence | The complaint of involuntary leakage on effort or exertion, or on sneezing or coughing |

| Mixed incontinence | The complaint of involuntary leakage associated with urgency and also with exertion, effort, sneezing, or coughing |

| Continuous urinary incontinence | The complaint of continuous leakage |

| Other types of urinary incontinence | Situational incontinence (e.g., during sexual intercourse or giggle incontinence) |

| Dependent continence | Situation in which the individual would suffer a recurrence of incontinence if management was withdrawn |

| Contained incontinence | Situation in which incontinence is controlled by being contained in an absorbent product or collecting device (previously “social continence”) |

| Overactive bladder | Urgency with or without urgency incontinence usually with increased daytime frequency and nocturia |

Data from Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-Committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn 2002;21:167–78 (reprinted in Urology 2003;61:37–49).

The classification of POP is categorized according to the affected compartment. Simply put, anterior compartment prolapse (cystocele) generally involves descent of the bladder toward the vaginal lumen, posterior prolapse (rectocele) involves the rectum compressing the posterior vaginal wall into the vagina, and apical prolapse is associated with descent of the uterus (uterine procidentia) and/or the bowel (enterocele) at the top of the vagina. Several grading systems exist to quantify the severity of POP and are discussed later and illustrated in Figure 64–1.

Figure 64–1 Visual comparison of systems used to quantify pelvic organ prolapse

(From Theofrastous JP, Swift SE. The clinical evaluation of pelvic floor dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 1998;25:783–804.)

Regarding incontinence specifically, the substantiation of a proper diagnosis requires direct observation of urinary leakage by the clinician (Nitti and Blaivas, 2007). It is the belief of many experts that no patient should undergo invasive or irreversible therapies without definitive establishment of the cause of their incontinence. Complete and extensive evaluation can facilitate accurate diagnosis of PFDs to promote optimal treatment planning and counseling of patients.

Key Points: General Considerations

History

A careful history should always be obtained from the patient. However, several studies have indicated that patient history alone is not completely accurate as the sole determinant of incontinence type (Summitt et al, 1992; Jensen et al, 1994). Bates and colleagues (1973) are credited with the dictum, “The bladder is an unreliable witness,” which has been corroborated by many investigators in various forms. Accordingly, all available information including that which is obtained by supplementary examinations should be integrated into the diagnosis.

History of Present Illness

A thorough history is imperative in the evaluation of incontinence. Several queries should be included in a continence and pelvic floor history in order to best portray the patient’s symptoms (Holroyd-Leduc et al, 2008). The incontinence should first be characterized subjectively. Does the leakage occur (1) with physical activity? (2) with a sense of urgency? or (3) without sensory awareness? If the nature of the incontinence is mixed, does one component cause more bother or occur more frequently than the other? Second, the leakage should be quantified if possible. Appraisal of the degree of leakage before therapy can be helpful during postoperative assessment of treatment impact. For the purposes of routine outpatient assessment, this quantification can be achieved on the basis of the number of pads used per day or the frequency of clothing changes due to urinary leakage. In the setting of research or an academic practice, more stringent and objective measures such as pad weight testing are often used (see “Supplemental Evaluation” later). Third, the voiding pattern should be defined. What is the frequency of urination during the day? During the night? Are there any obstructive symptoms? Does the patient feel as though he or she empties the bladder completely? Is the stream strong or does it “trickle”? Does the stream fluctuate during the void? Is it necessary to push or strain or change posture to void or empty the bladder? Fourth, establishment of the duration of symptoms and any inciting events that contributed to the onset of leakage is important. Did the leakage follow a pregnancy or a vaginal delivery? How long ago? Did the leakage start after a strain, a fall, or trauma? Has the patient undergone pelvic or back surgery? In males, has there been any prostate or urethral surgery for benign or malignant disease? Has there been any lower urinary tract instrumentation? Are there any accompanying neurologic symptoms such as numbness or tingling in the extremities, blurry/double vision, balance or coordination changes, or tremor? Finally, it is helpful to determine the impact that the leakage has on the patient’s daily life and activities. Does the incontinence limit the individual’s activity? Has the patient changed his or her lifestyle due to the threat of leakage?

In women the gynecologic and obstetric history including gravity, parity, and hormonal status is important. Determination of whether the patient is premenopausal, perimenopausal, or postmenopausal, and whether or not she has used any exogenous hormones such as oral contraceptives or local or systemic hormone replacement therapy can be helpful in her overall assessment. As mentioned earlier, although beneficial effects of local hormone replacement therapy are well-established, there have been reports that exogenous hormone therapy can actually increase the risk of SUI (Townsend et al, 2009).

Clearly, previous pelvic surgery can affect LUT function. Anti-incontinence surgery, POP repair, and hysterectomy can contribute to a variety of urinary symptoms in women. Similarly, a history of prostate surgery can give rise to voiding or leakage complaints in men. Abdominoperineal resection can result in neurologic injury that can affect the function of either the bladder or the sphincter (Petrelli et al, 1993), and back surgery can cause a variety of symptoms dependent on the level affected.

Medications

An accurate assessment of medications is critical, particularly in the elderly patient population in whom polypharmacy is common. Many agents can affect urine production, LUT function, and mental status, all of which can have an impact on continence. Special attention should focus on agents that can affect bladder/sphincteric function. Table 64–3 categorizes some commonly used classes of medications by mechanism of action and potential effect on the LUT.

Table 64–3 Pharmacologic Agents That Can Affect the Lower Urinary Tract

| PHARMACOLOGIC EFFECTS | POTENTIAL EFFECTS ON URINARY TRACT |

|---|---|

| Sympathomimetics | Can increase outlet resistance and exacerbate obstructive symptoms/overactive bladder symptoms |

| Can decrease detrusor contractility and precipitate retention | |

| Sympatholytics | Can decrease outlet resistance and exacerbate stress incontinence |

| Anticholinergics | Can contribute to urinary retention, particularly in patients with outlet obstruction |

| Diuretics | Do not affect bladder directly, but because of increased urine production, can aggravate incontinence problems |

Other

As genetics can influence connective tissue integrity, it stands to reason that there may be a potential hereditary role in continence and POP (Twiss et al, 2007). Therefore inquiry about family history of POP may be helpful. Additionally, a thorough review of systems may reveal symptoms that suggest other conditions that could affect pelvic floor function.

Male incontinence, also a prevalent health issue, should be assessed in much the same way as female incontinence, although specific consideration of the impact of the anatomy specific to the male should be considered. Benign prostatic hyperplasia, the evaluation of which is covered in detail in Chapter 92, can cause secondary urgency and urgency incontinence in addition to more “typical” obstructive symptoms such as a decreased force of stream, urinary hesitancy, intermittency, and incomplete bladder emptying. Prostate surgery for benign or malignant disease can contribute to SUI. With this in mind, full assessment of male LUT symptoms (LUTS) should be performed to facilitate proper treatment planning.

Key Points: Evaluation—History

Physical Examination

Per Medicare coding guidelines (Centers for Medicare/Medicaid, 1997), a female pelvic examination includes at least 7 of the 11 bullet items listed in Table 64–4. The external genitalia should be evaluated with regard to general appearance, estrogen status, lesions, and labial size and adhesions. Estrogen status can be evaluated on the basis of the presence or absence of a urethral caruncle, urethral prolapse, and/or labial adhesions, all of which, if present, may indicate estrogen deficiency. Likewise, attention to the overall tissue appearance and color is important. Hormonally deficient vaginal tissue has a pale, flat, dry appearance with no rugae, as opposed to the healthy, pink rugae of well-estrogenized tissue.

Table 64–4 Components of a Focused Pelvic Examination

• Inspection and palpation of breasts (e.g., masses or lumps, tenderness, symmetry nipple discharge) |

At press time, 7 of 11 bullet points listed above are required to be considered a complete female genitourinary examination. However, other organ systems/body areas not limited to the genitourinary system may be included in a report to accomplish the requirements of various levels of examination.

Data from Centers for Medicare/Medicaid (CMS): Single organ system examination—Genitourinary: 1997 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management (E/M) Services, jointly approved by the American Medical Association and HCFA with revisions November, 1997.

Urethral position and mobility should be assessed at rest and with straining and coughing. The Q-tip test was developed to objectify the evaluation of urethral mobility (Bergman and Bhatia, 1987; Walters and Diaz, 1987). The discomfort caused to the patient during insertion of the Q-tip can be minimized with the use of intraurethral lidocaine jelly. The Q-tip is inserted into the bladder through the urethra, and the angle that the Q-tip moves from horizontal to its final position with straining is measured. Hypermobility is defined as a Q-tip angle of greater than 30 degrees from horizontal.

Assessment of prolapse should ideally be performed in both the lithotomy and standing positions, the latter facilitated by having the patient stand with one foot elevated on a short stool. Each compartment—the anterior, posterior, and apical (uterus/cervix or vaginal cuff)—should be evaluated methodically and the perineal body assessed for laxity. A complete systematic examination is performed using two posterior blades of a split Grave speculum with and without straining. First, one blade is used to retract the posterior wall to facilitate anterior compartment examination. The blade is then repositioned to retract anteriorly for examination of the posterior compartment. Finally, both blades are inserted simultaneously, one anteriorly and one posteriorly, to isolate the vaginal apex and facilitate examination of the cervical or cuff support. The posterior blade is slowly withdrawn to examine the posterior wall. Next, with the posterior blade in place, the patient is asked to strain. Foreshortening of the posterior wall causes expulsion of the blade and suggests a compromise in the level I support (Delancey, 1992) (cardinal-uterosacral ligament complex) of the vault; if the blade remains in place, this could represent an isolated rectocele or enterocele without vault prolapse. Evaluation for occult SUI should be performed with the anterior wall supported. SUI can be masked if significant prolapse “kinks” the urethra and outlet.

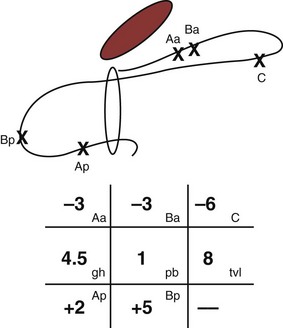

Several classification systems are used to quantify POP, the most widely used of which are the Baden-Walker classification (Baden et al, 1968) and the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification system, known as the “POP-Q” (Bump et al, 1996). The two systems are juxtaposed in Figure 64–1. In the POP-Q system, which was created in an effort to provide objectivity to POP quantification, nine specific points of measurement are obtained in relation to the hymenal ring as illustrated in Figure 64–2A and B. Six vaginal points labeled Aa, Ba, C, D, Ap, and Bp are measured during Valsalva maneuver. Points above the hymen are considered negative and points below the hymen are positive. The genital hiatus (gh) represents the size of the vaginal opening, and the perineal body (pb) represents the distance between the vagina and the anus. The total vaginal length (tvl) is measured by reducing the prolapse and measuring the depth of the vagina. Table 64–5 contains the POP-Q staging criteria, a simplified presentation of the POP-Q system, and Figure 64–3 illustrates an example of the application of the system.

Figure 64–2 A, Landmarks for the POP-Q system. B, POP-Q Points of Reference.

(A, From Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;175:10–7.)

Table 64–5 POP-Q Staging Criteria

| STAGE | CRITERIA |

|---|---|

| 0 | Aa, Ap, Ba, Bp at −3 cm and C or D ≤ −(tvl − 2) cm |

| I | Stage 0 criteria not met and leading edge < −1 cm |

| II | Leading edge ≥ −1 cm but ≤ +1 cm |

| III | Leading edge > +1 cm but < +(tvl − 2) cm |

| IV | Leading edge ≥ +(tvl − 2) cm |

(From Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;175:10–7.)

Key Points: Evaluation—Physical Examination

Supplemental Evaluation

Symptom Quantification Instruments

Voiding Diaries

Instruments such as voiding diaries, questionnaires, and pad tests have been developed to aid in the quantification of urinary loss, both symptomatically and volumetrically. Voiding diaries can provide both diagnostic and therapeutic advantages. The use of diaries often helps patients realize their pattern of urination and is more accurate than recall (Larsson et al, 1984; McCormack et al, 1992; Siltberg et al, 1997). Furthermore, the diary can provide patients with insights into those behaviors that can be altered to decrease urinary frequency (Burgio, 2004).

Several studies have demonstrated the adjunctive role that diaries can have in the diagnosis and management of incontinence. Diaries can be helpful over routine subjective history because patient recall is often not as accurate as a formal voiding diary in ascertaining urinary frequency. In a retrospective review of 601 patients who underwent sling surgery and completed bladder diaries, only 47% were accurate about their daytime frequency; 51% overestimated their diurnal frequency, and this overestimation was exaggerated in those who reported voiding more than 10 times a day (Stav et al, 2009). Overestimation rates were similar between patients with and without overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms. Interestingly, 93% of women in this study were accurate about their nighttime frequency. In another study of women with UI, it was noted that the overestimation of incontinence episode frequency occurred more often in those patients who were more bothered by their incontinence. Conversely, Ku and colleagues (2004) found a poor correlation between subjective nocturnal frequency and that noted by 164 patients on their frequency volume charts. Wyman and colleagues (1987) similarly showed a higher correlation of diary-reported frequency in the daytime versus the night.

Martin and colleagues (2006) performed a meta-analysis of 121/6099 papers that compared two or more diagnostic techniques for incontinence and showed that diaries are most cost-effective when used in conjunction with history, particularly in patients undergoing treatment for detrusor overactivity (DO). It should be noted, however, that diaries should not substitute for more formal studies in select patients. One study that retrospectively assessed the Larsson frequency/volume chart as compared with the cystometrogram in 216 patients demonstrated the sensitivity and specificity of the chart with regard to DO to be 52% and 70%, respectively, and with regard to SUI, 66% and 65%, respectively (Tincello and Richmond, 1998). For daily clinical practice, 24-hour diaries should suffice to obtain valuable clinical information regarding LUT function; in academic studies, longer diaries may be requested, but this should be balanced with the well-established knowledge that the more complex a given instrument is (i.e., the more data requested), the lower patient compliance will be in completing it (Groutz et al, 2000).

Questionnaires and Quality of Life Instruments

Questionnaires can provide a helpful complement to the patient history and patient-reported outcomes (PROs). A plethora of instruments to evaluate symptoms, degree of bother, and QoL in patients with incontinence and PFDs have been developed in an effort to provide optimal assessment of outcomes and to eliminate the confounding issue of physician bias; many have been validated. Table 64–6 contains validated questionnaires highly recommended by the International Consultation on Incontinence (ICI). One such instrument, the modular ICIQ, was developed by the ICI in an effort to collaboratively develop a universally applicable instrument that could be used internationally to assess pelvic floor function in both clinical practice and research settings (Abrams et al, 2005) and has accordingly been translated in 38 languages. The short form of the ICI questionnaire (ICIQ-SF) has been shown to correlate nicely with both the 1-hour (Franco et al, 2008) and 24-hour (Karantanis et al, 2004

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree