Chapter 32 Evaluation of Gastric Polyps and Thickened Gastric Folds

Introduction

Gastric polyps are detected in 3% of upper endoscopic evaluations,1 but the incidence is higher than in the past because of the increasing use of endoscopy for diagnosis and treatment of upper digestive tract diseases.2 These polyps are usually asymptomatic and are often found incidentally on endoscopic or radiographic examination. They may occur sporadically or be associated with polyposis syndromes. Gastric polyps may be single or multiple in number and pedunculated or sessile in form. Depending on the type of polyp, variable sizes can be encountered ranging from millimeters to several centimeters in diameter. Generally, gastric polyps are usually small (diameter <1 cm), well circumscribed, clearly demarcated, and project above the level of surrounding mucosa. Because of its diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic ability, endoscopy is the examination of choice in the diagnosis and treatment of gastric polyps.

Gastric polyps can be divided into epithelial and nonepithelial lesions. This chapter reviews the various types of epithelial gastric polyps and discusses the endoscopic techniques of gastric polypectomy, surveillance, and management. Nonepithelial gastric tumors including submucosal tumors are discussed in Chapter 29, and the management of upper gastrointestinal (GI) hereditary polyposis syndromes is discussed in Chapter 34. This chapter concludes with a discussion of the evaluation of thickened gastric folds, differential diagnoses, and endoscopic techniques and management.

Epithelial Gastric Polyps

Epithelial gastric polyps are divided into nonneoplastic and neoplastic lesions. In contrast to colonic polyps, most gastric polyps are nonneoplastic (80%–90%), including fundic gland and hyperplastic polyps. Although hyperplastic polyps are not neoplastic, dysplasia or gastric adenocarcinoma, or both, may rarely develop within the lesion.3 Neoplastic epithelial gastric polyps include adenomas and polypoid gastric carcinomas.

Fundic Gland Polyps

Fundic gland polyps (also known as Elster’s glandular cysts and cystic hamartomatous epithelial polyps) constitute up to 77% of all gastric polyps and are observed in 3.2% of routine upper endoscopy procedures.4 They are more common in women and patients with Helicobacter pylori infection.5,6 The pathogenesis is unknown. These polyps usually occur sporadically but at increased frequency in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and patients receiving long-term proton pump inhibitor treatment.6,7 Although fundic gland polyps are traditionally considered a condition with little or no malignant potential, some reports have shown a possible increased association of concomitant colorectal adenomas or carcinomas in patients with fundic gland polyps.8,9 Dysplasia and adenomatous changes in fundic gland polyps have developed in 1% to 1.9% of sporadic cases10 and in 25% to 44% of patients with FAP.9,11 In addition, reports have suggested malignant transformation of fundic gland polyps in patients with FAP, which may occur more often than previously believed.11,12 Management of FAP syndrome is discussed in Chapter 34. The development of fundic gland polyps has also been associated with long-term proton pump inhibitor use,13–15 but some studies have shown that a causal pathogenetic relationship is unlikely.16,17

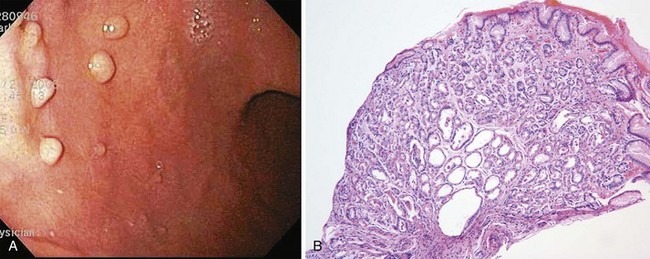

Histologically, fundic gland polyps are characterized by dilated glands forming microcysts lined with fundic-type parietal and chief cells. Endoscopically, fundic gland polyps are usually found in the fundus or body of the stomach (Fig. 32.1). They may be found as a solitary lesion, but are often multiple in closely packed clusters, resembling small round grapes. These lesions are generally 2 to 3 mm in diameter, and because of their small size, they are sometimes hidden between folds. The mucosal surface typically is the normal surrounding mucosal color but also can be pale in coloration; visualization is best when the stomach is fully distended.

Hyperplastic Polyps

Hyperplastic polyps are another common polypoid lesion in the stomach, constituting 73% of all gastric polyps in some series.18 The large variability in frequency is likely due to differing definitions of hyperplastic polyps. Men and women are equally affected, with predominance in adults older than 60 years. These polyps have previously been regarded as having no malignant potential; however, this is no longer thought to be true because of the increasing number of dysplastic changes or carcinoma found in gastric hyperplastic polyps.3,19,20 Focal carcinomas occurred in 2.1% of gastric hyperplastic polyps in one large Japanese series.21 In addition, within the same series, foci of dysplasia were seen in 4.0% of gastric hyperplastic polyps. The prevalence of true dysplasia arising from hyperplastic polyps is debated, with reported rates ranging from 1.9% to 19%.22 In contrast to gastric fundic gland polyps that tend to arise from otherwise normal gastric mucosa, hyperplastic polyps have been associated with chronic gastritis, particularly with autoimmune gastritis,22–24 and H. pylori gastritis.25 It has been shown more recently that H. pylori eradication leads to hyperplastic polyp disappearance26,27; this may provide an initial medical therapy before endoscopic removal.

The histology of gastric hyperplastic polyps differs from that of hyperplastic colorectal polyps in that gastric ones have submucosal edema with prominent foveolar hyperplasia and inflammation of the lamina propria. Endoscopically, hyperplastic polyps can be found throughout the stomach and range in size from small nodules of a few millimeters to a large mass of many centimeters that may be mistaken for carcinoma. They can be solitary or multiple and may be sessile or pedunculated with an associated stalk. If multiple polyps are found, the prevalence of associated atrophic gastritis may be 20% to 30%, and the polyps usually are more proximal in location.22,28 The overlying mucosa may be normal in appearance, but the mucosa often has a reddish coloration in larger polyps (Fig. 32.2). Because of local trauma, larger hyperplastic polyps often have a friable, ulcerated whitish tip of granulation tissue and may be surrounded by atrophic or inflamed-appearing mucosa. There is no consensus regarding endoscopic removal and surveillance of hyperplastic gastric polyps. Details of management are discussed later.

Gastric Adenomatous Polyps

Adenomatous polyps of the stomach are less common than nonneoplastic epithelial lesions, constituting 7% to 10% of gastric polypoid lesions.29,30 Gastric adenomas are true neoplasms and are premalignant lesions with an increasing risk of developing into adenocarcinoma depending on the size and structure. Up to 24% of gastric adenomas may harbor a focus of adenocarcinoma, especially if greater than 2 cm in diameter.31 Malignancy can be found in lesions of any size, however. These lesions often arise in stomachs with a background of mucosal atrophy and are a marker for increased risk of adenocarcinoma elsewhere in the stomach.30,32 Gastric adenomas have been associated with FAP but not as frequently as fundic gland polyps.

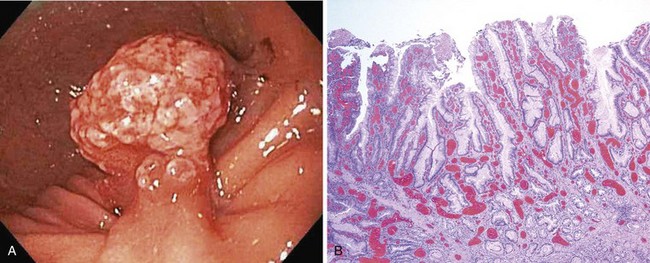

Histologically, gastric adenomas are characterized by columnar epithelium that is pseudostratified and shows elongated atypical nuclei and increased mitotic activity; they can be divided into tubular, villous, and tubulovillous types. Dysplasia and carcinomatous changes occur most often in villous and tubulovillous adenomas (28.5% to 40%).33–36 Endoscopic evaluation of gastric adenomas should consist of a careful complete examination of the surrounding mucosa and biopsy of any suspicious lesion. These lesions can be found in any location of the stomach but seem to have a predilection for the antrum.37 Gastric adenomas are generally larger than hyperplastic polyps, usually around 3 to 4 cm in diameter, but can also range in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters. The mucosal surface is usually smooth with a reddish coloration and often with a cerebriform mucosal pattern. The shape of gastric adenomas can vary, ranging from single, round, sessile projections to multilobulated lesions. Villous-type lesions are sometimes difficult to detect because of the flat, sessile, carpetlike appearance that can blend in with the surrounding rugae. Rarely, flat or depressed adenomas are encountered.38

Because of their malignant potential, the consensus is that all gastric adenomatous polyps need to be completely removed either endoscopically or by laparoscopic wedge resection. In addition, a thorough biopsy of the surrounding gastric mucosa should be performed. The recurrence rate of adenomatous polyps may be 16% after polypectomy.39 Endoscopic techniques and management are discussed in more detail later.

Polypoid Gastric Carcinoma

Because of similar appearance, endoscopic determination of adenomatous gastric polyps versus genuine malignant lesions is extremely difficult without histologic confirmation. Synchronous or metachronous gastric cancers have been found in 11% of patients with adenomas.34 Gastric adenocarcinomas may develop as polypoid lesions (Borrmann type A) and are differentiated into type I (protruded, polypoid type) and type IIa (superficial elevated type).40

Subepithelial Gastric Polyps

Subepithelial gastric polyps consist of a heterogeneous group of lesions that are usually small and difficult to differentiate between hyperplastic and adenomatous polyps. These nonepithelial lesions are usually covered by normal-appearing mucosa and have various causes, including carcinoid tumors, lipomas, aberrant pancreas (pancreatic rest, heterotopic pancreas), inflammatory fibroid polyps, and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (including leiomyomas, leiomyosarcomas, schwannomas, fibromas, and others). Chapter 29 contains a complete discussion of nonepithelial tumors of the stomach.

Endoscopic Techniques and Management

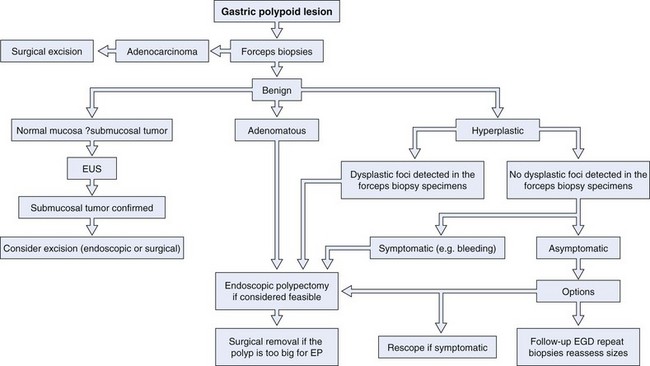

Gastric polyps are rarely symptomatic and often discovered incidentally. The first step in the management of a gastric polyp is to identify the tissue histology (Fig. 32.3). Because the histology of a gastric polyp cannot be reliably distinguished using a standard endoscope, biopsy or excision of gastric polypoid lesions found on upper endoscopy should be performed. This recommendation may change, however, as more studies using magnification or zoom endoscopy identify mucosal patterns that correlate with histology.41,42 Although forceps biopsy is a simple method of obtaining tissue, it may provide inadequate tissue or sampling error. Studies have shown inconsistencies between histologic diagnosis made by forceps biopsy and a subsequent snare polypectomy specimen.43,44 Muehldorfer and coworkers45 conducted a prospective multicenter study comparing the diagnostic accuracy of forceps biopsy versus polypectomy in 222 gastric polyps greater than 5 mm (excluded fundic gland polyps). Relevant differences were found in 2.7% of cases in which there was failure to reveal foci of carcinoma on forceps biopsy in a group of hyperplastic polyps. Similarly, a study from Hungary showed significant disagreements in 27% of cases.43 Endoscopic removal of all epithelial gastric polyps larger than 5 mm is encouraged by these authors.

Fig. 32.3 Evaluation and management of a gastric polypoid lesion.

(Adapted from Lau CF, Hui PK, Mak KL, et al: Gastric polypoid lesions—illustrative cases and literature review. Am J Gastroenterol 93:2559–2564, 1998.)

If multiple gastric polyps are found, additional risk is presented to the patient if multiple snare excisions are performed. Although complete excision is preferred, this may not be technically feasible or practical; the risks and benefits should be individualized for each patient. In this scenario, resection could be delayed until forceps biopsy results are reviewed. Although gastric polyps that are multiple in number are usually of the same histologic type,46 hyperplastic and adenomatous polyps can be found together.35,39 One strategy to use when addressing multiple gastric polyps is to remove the larger polyps when feasible and safe by snare excision and perform multiple forceps biopsies of the smaller polyps. It is hoped that this approach would give a complete representation of the histology of the lesions encountered, while minimizing risk of a missed neoplasm. If one or more foci of dysplasia are detected in a biopsy specimen from a gastric hyperplastic polyp, the polyp should be removed, even if it is not symptomatic.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree