Evaluation of Colorectal Dysfunction

Marc R. Toglia

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal disorders occur commonly among adult women and are associated with diverse symptoms, including abdominal pain and bloating, constipation, incomplete defecation, and fecal incontinence. To adequately care for women with these disorders, clinicians must have an adequate understanding of the physiology and pathophysiology of the colon and anorectum.

OVERVIEW OF NORMAL COLORECTAL FUNCTION

Stool Formation and Colonic Transit

Voluntary storage and evacuation of the stool is a complex neuromuscular mechanism that involves many physiologic processes. Intestinal transit and absorption, colonic transit, rectal compliance, anorectal sensation, and sphincteric mechanism all play an important role in normal colorectal function. An understanding of how each of these variables affects continence is essential in the proper diagnosis and treatment of the women with colorectal disorders.

A major function of the colon is the final regulation of water and electrolyte absorption. The colon is capable of absorbing up to 5 L of water and associated electrolytes in 24 hours. Stool content is propelled along the large intestine via contractile waves know as peristalsis. Colonic motility is complex, with great regional heterogeneity. Functionally, the colon can be divided into three segments: the proximal colon, the segment from the midtransverse colon to the proximal rectosigmoid, and the rectosigmoid. The rectosigmoid is uniquely adapted for sodium and water absorption. The transit of the stool content is significantly delayed in this region to permit complete reabsorption of fecal water and electrolytes before final elimination.

Anorectal Continence

The voluntary storage and evacuation of solid waste is a complex physiologic process involving learned social behavior, voluntary cortical control, and a series of involuntary reflexes. When stool content first enters into the rectal vault, several physiologic events take place. The arrival of stool in the rectum is associated with a transient decrease in internal anal sphincter tone and an increase in external sphincter activity; this is known as the rectoanal inhibitory reflex. This allows the sensory-rich anal canal to come in contact with the rectal contents to determine whether it contains solid, liquid, and/or gas. This physiologic event is known as sampling. This is followed by a relaxation of the rectum to store the increased rectal volume in a process known as accommodation. The rectum, like the bladder, is a highly compliant reservoir that facilitates storage of waste. As rectal volume increases, an urge to defecate is experienced. If this urge is voluntarily suppressed, the rectum relaxes further to continue the accommodation of stool. Rectal compliance may be decreased in certain disease states such as ulcerative proctitis or radiation proctitis. A loss in compliance may decrease the ability of the rectal wall to stretch, and as a result, rectal pressure remains high. This may compromise this first part of the continence mechanism and place an increased demand on the sphincteric mechanism.

The anal canal is primarily responsible for preventing leakage of stool during this phase of rectal storage. The anal canal remains closed as the result of the interactions between three distinct muscles: the puborectalis portion of the levator ani, the

external anal sphincter, and the internal anal sphincter. The puborectalis and external anal sphincter comprise a unique type of striated muscle that is capable of maintaining a constant resting tone that is proportional to the volume of the rectal content and that relaxes at the time of defecation. Both of these muscles contain a majority of type I (slow-twitch) muscle fibers, which are ideally suited to maintaining a constant tone over time. Each muscle group also contains a smaller proportion of type II (fast-twitch) fibers, which allows them to respond quickly during sudden increases in intra-abdominal pressures (1).

external anal sphincter, and the internal anal sphincter. The puborectalis and external anal sphincter comprise a unique type of striated muscle that is capable of maintaining a constant resting tone that is proportional to the volume of the rectal content and that relaxes at the time of defecation. Both of these muscles contain a majority of type I (slow-twitch) muscle fibers, which are ideally suited to maintaining a constant tone over time. Each muscle group also contains a smaller proportion of type II (fast-twitch) fibers, which allows them to respond quickly during sudden increases in intra-abdominal pressures (1).

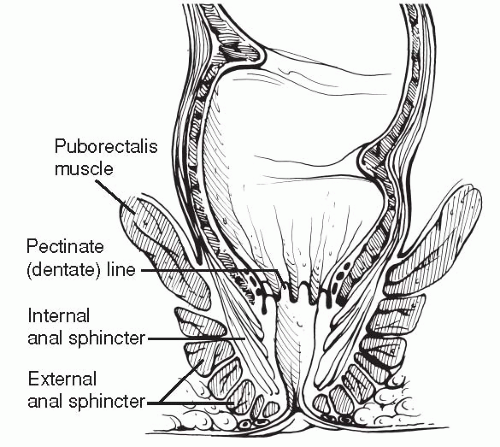

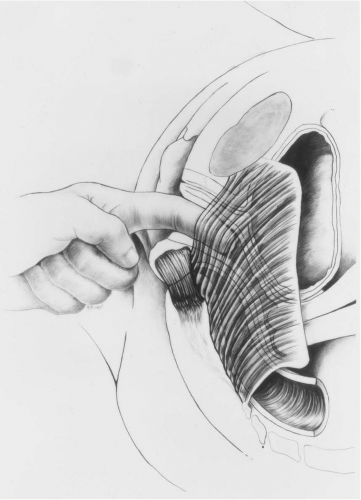

Continence of solid stool is maintained primarily by the actions of the puborectalis. This muscle originates from the pubic rami on either side of the midline at the level of the arcus tendineus levator ani. The muscle fibers pass laterally to the vagina and form a U-shaped sling that cradles the rectum. The constant resting tone of the puborectalis pulls the anorectal junction towards the pubic symphysis, creating a 90-degree angle between the anal and rectal canals referred to as the anorectal angle (Fig. 21.1). This angulation is easily palpated on digital rectal examination. It was once proposed that this acute angulation creates a “flap-valve” effect in which an increase in intraabdominal pressure compresses the anterior rectal wall against the pelvic floor, and that this action was critical to maintaining continence. However, more recent physiologic studies have failed to demonstrate that such a mechanism exists (2,3), and successful surgical restoration of anal continence does not appear to depend upon the restoration of this angle (4,5). Defecation of solid stool is initiated by the voluntary relaxation of the puborectalis, which together with intestinal peristalsis, a voluntary increase in intra-abdominal pressure, and relaxation of the external and internal anal sphincters, allows for the passage of stool downward through the anal canal. The effectiveness of the puborectalis muscle in maintaining continence without the external or internal anal sphincter is illustrated by the relative continence that women with a chronic fourth-degree laceration have over solid stool.

FIGURE 21.1 ● Lateral view of the external anal sphincter and levator ani muscles showing palpation of the medial border of the levator ani muscle (puborectalis-pubococcygeus portion). Note the approximately 90-degree angle between the anal canal and the axis of the rectum. (From Toglia MR, DeLancey JOL. Anal incontinence and the obstetrician gynecologist. Obstet Gynecol 1994;84;4(2):731-740, with permission.) |

The internal and external anal sphincters maintain continence below the level of the puborectalis (Fig. 21.2). These two structures are critical in the control of flatus and liquid feces, as the puborectalis mechanism is ineffective in this regard. The shape of the combined internal and external

sphincter muscles is nearly cylindrical as it encircles the anal canal and, measured in the midline, is approximately 18 mm thick and 28 mm long (6). It is critical that clinicians recognize that 50% of the anterior thickness of the sphincter complex is attributable to the internal anal sphincter. The anatomic and functional importance of the internal anal sphincter is often underappreciated in most textbooks on obstetric and gynecologic surgery, but it is believed to be critical in the proper repair of obstetric sphincter lacerations as well as the surgical correction of anal incontinence.

sphincter muscles is nearly cylindrical as it encircles the anal canal and, measured in the midline, is approximately 18 mm thick and 28 mm long (6). It is critical that clinicians recognize that 50% of the anterior thickness of the sphincter complex is attributable to the internal anal sphincter. The anatomic and functional importance of the internal anal sphincter is often underappreciated in most textbooks on obstetric and gynecologic surgery, but it is believed to be critical in the proper repair of obstetric sphincter lacerations as well as the surgical correction of anal incontinence.

The internal anal sphincter is a thickened, downward continuation of the circular smooth muscle layer of the colon and is innervated by sympathetic nerves from the presacral complex. Unlike the external anal sphincter and puborectalis muscle, the internal anal sphincter is not under voluntary control, and its function is mediated largely by reflex arcs at the spinal cord level. At rest, the anal canal is kept closed by the constant tonic activity of both the internal and external anal sphincters. Physiologic studies suggest that the internal anal sphincter is responsible for 75% to 85% of the resting tone of the anal canal (7,8). As the intestinal content passes into the rectum, the internal anal sphincter relaxes reflexively to allow the upper anal canal to “sample” the contents and to discriminate between solid, liquid, and gas. Once the intestinal contents have been determined, the internal anal sphincter contracts again to augment closure of the anal canal. Thus, it is currently believed that continence at rest (particularly for liquid stool and flatus) is largely the responsibility of the internal anal sphincter, whereas continence during sudden distention of the anal canal is principally maintained by the external anal sphincter (9).

Anal sensation is also thought to play a critical role in the normal continence mechanism. Sensory receptors located within the anal canal and within the levator ani muscles detect the presence of stool in the rectum as well as the degree of rectal distention. The upper anal canal is capable of distinguishing between solid, liquid, and gaseous forms of stool, and feedback from these sensory organs is important in coordinating the actions of the sphincteric musculature.

The anal canal cushions (hemorrhoids) are thought to assist in the continence mechanism by facilitating mucosal coaptation. These vascular channels fill with blood and may occlude the lower anal canal. Supporters of this theory suggest that the loss of these structures following hemorrhoidectomy may account for the reported incidence of incontinence following this procedure.

Defecation

Defecation is a highly coordinated physiologic action that involves neuromuscular regulation by the central nervous system. Distention of the rectum by the stool content initiates the rectoanal inhibitory reflex discussed previously and allows the sensory-rich upper anal canal to sample stool content. The act of defecation is initiated by a Valsalva maneuver to raise intra-abdominal and intrarectal pressure. Voluntary inhibition of the external anal sphincter and puborectalis enables the rectum to empty. This is assisted by coordinated peristaltic activity of the rectosigmoid. When evacuation is completed, the external anal sphincter and puborectalis contract (termed the closing reflex) and the continence mechanism is initiated again.

SYMPTOM-BASED APPROACH TO COLORECTAL DISORDERS

Clinicians who care for women with pelvic floor disorders are commonly asked to evaluate patients with two separate syndromes involving colorectal disorders. The first syndrome involves symptoms suggestive of disordered defecation, and the second syndrome involves symptoms of fecal incontinence.

Disordered Defecation

Women with disordered defecation will typically refer to their symptoms as “constipation.” Constipation frequently has different meanings to different people. Commonly accepted definitions include infrequent stools (less than three per week), passing stool that is too hard or too small, difficulty or prolongation of the act of defecation (“straining”), or a feeling of rectal fullness or incomplete evacuation. Abdominal pain and bloating are frequently the predominant complaint in constipated patients. Therefore, the first step in managing constipation is to understand what the patient means by using that term. It may be helpful to classify patients with constipation into one of three categories: (a) those with colonic motility disorders, (b) those with pelvic outlet obstructive symptoms, and (c) those with a combination of both (10) (Table 21.1). History, physical examination, and ancillary testing can distinguish them.

Clinicians should question the patient carefully to determine the following historical data: number of bowel movements per week, length of time spent on the commode, pain associated with defecation, sensation of incomplete evacuation or a false sense of the need to evacuate, need to digitally assist defecation by either splinting the perineum or extracting feces from the anus directly, and presence of a bulge, either vaginal or rectal. Physical examination may reveal the presence of pelvic organ prolapse, including a rectocele, enterocele, or rectal prolapse; fecal impaction; poor sphincter tone; or spasm of the puborectalis muscle. Proctoscopy is helpful in the detection of anal fissures, edema, internal hemorrhoids, or a solitary rectal ulcer. The presence of rectal bleeding should prompt referral to an appropriate specialist. Ancillary testing will be discussed later.

TABLE 21.1 Causes of Constipation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Systemic Factors

After inadequate dietary fiber, drug therapy is probably the most common cause of constipation. Common prescription and over-the-counter medications that may cause constipation are listed in Table 21.2. Many systemic factors may affect normal colonic factors and cause constipation. The prevalence of constipation during pregnancy is well recognized. Hypothyroidism, diabetes, hyperparathyroidism, and severe electrolyte abnormality can also cause constipation. Uncommon diseases such as scleroderma and amyloidosis can cause structural changes in the intestine that can lead to constipation. Neurologic diseases involving the central nervous system such as multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease are frequently associated with constipation.

Colonic Motility Disorders

A deficiency in dietary fiber has long been thought to be an important cause of constipation. Fiber may shorten whole gut transit and increase stool weight. Primary therapy for constipation consists of a diet trial with approximately 30 g of dietary

fiber per day for 4 to 6 weeks coupled with an adequate intake of fluid.

fiber per day for 4 to 6 weeks coupled with an adequate intake of fluid.

TABLE 21.2 Drugs Commonly Associated with Constipation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Colonic inertia, or slow transit constipation, is a condition of chronic idiopathic constipation in which patients are found to have no organic cause for their symptoms and have diffuse, pancolonic marker delay on transit study. Megacolon or megarectum may or may not be present in association with colonic inertia. Colonic inertia is found almost exclusively in women, and some studies suggest an unusually high prevalence of psychiatric disturbances among these patients (11). Some patients with megacolon have a loss of the normal myenteric plexus ganglion cells, which is considered diagnostic of Hirschsprung’s disease and usually presents in childhood or early adulthood.

Anorectal Outlet Obstruction Syndromes

Functional outlet obstruction is common cause of constipation in women. These patients typically have no obvious organic cause for their symptoms. Colonic transit studies reveal normal pancolonic transit time but delayed transit through the rectum. Anorectal outlet obstruction may be the manifestation of a variety of pelvic floor disorders listed in Table 21.1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree