Chapter 29 ERCP in Surgically Altered Anatomy

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is generally considered the technically most difficult endoscopic procedure. But it can be made more challenging if the gastrointestinal (GI) or pancreaticobiliary anatomy has been modified. A thorough understanding of a surgically altered anatomy is essential to minimize adverse events and to enhance the chance of a successful outcome. In virtually all of these cases, careful preprocedure planning is mandatory (Box 29.1).

Box 29.1

Preprocedure Planning in Situations That Involve Surgically Altered Anatomy

Esophageal Resection

Mostly done for esophageal neoplasm or premalignant conditions, up to 22% of esophageal resections may be accompanied by high esophageal anastomosis strictures.1 Additionally, a small diverticulum or malaligned lumen can form proximal to the anastomosis. When passing a duodenoscope, care must be taken to avoid forcing it through a diverticulum or an anastomotic stricture. If resistance is encountered, an end-viewing upper endoscope should be used to inspect the esophageal anatomy carefully. Esophageal resection also results in the stomach being brought up above the diaphragm and turned into a tubular sack that may end with a pyloroplasty. Once the duodenoscope has passed through the pylorus, the approach to the major papilla requires slightly more clockwise rotation or a longer insertion of the endoscope than usual.

Video for this chapter can be found online at www.expertconsult.com.

Gastric Resection

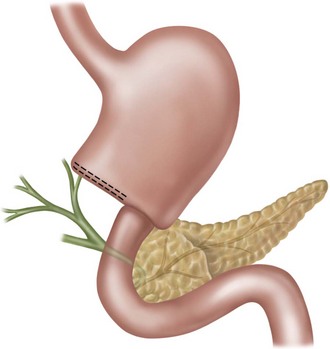

Billroth I

In a Billroth I surgery, only the antrum and pylorus are removed and the stomach is attached to the duodenum along its greater curvature (Fig. 29.1). Scope passage into the duodenum is typically easier than usual, but the papilla is harder to visualize. As expected, both the major and the minor papillae are more proximally located than usual. In the short-scope position, the papilla is seen following an exaggerated clockwise rotation of the endoscope. However, anchoring of the endoscope is difficult without the pylorus and achieving a stable scope position for deliberate cannulation can be quite difficult. In this situation, working in the long-scope position may be more desirable for bile duct cannulation because the papillary orifice is better visualized and the scope is more stably situated. Since it is difficult to cannulate the bile duct in a sharply retrograde fashion, using a sphincterotome and guidewire combination may overcome the intrinsic issue in a Billroth I cannulation.

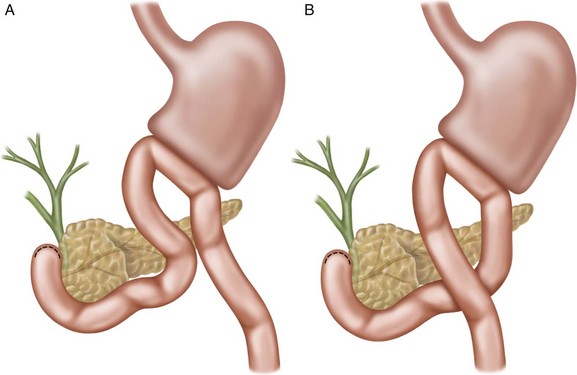

Billroth II

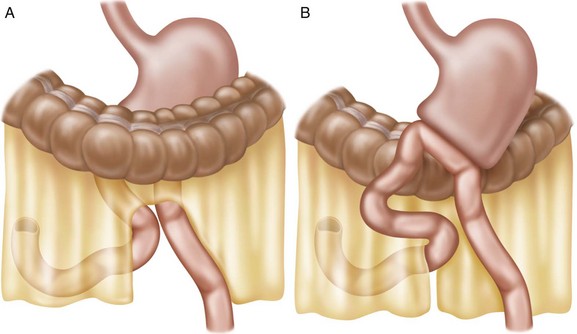

Before proton pump inhibitors were introduced, peptic ulcer surgery was common. A Billroth II operation involves an antrectomy and creation of a gastrojejunostomy. The result is an end-to-side (stomach-to-jejunum) anastomosis with an afferent and an efferent limb (Fig. 29.2) next to each other beyond the line of anastomosis. The afferent limb travels proximally and ends at the duodenal stump, whereas the efferent limb restores continuity with the rest of the GI tract. The major papilla is located near the duodenal stump and is seen with the papillary orifice facing the endoscope. There are several challenges that the endoscopist has to deal with when performing ERCP in a Billroth II stomach. It begins with the choice of endoscope. Once it was believed that an end-viewing endoscope was best used to navigate the small bowel and pass a cannula into the biliary orifice. But then many experienced biliary endoscopists switched to using side-viewing duodenoscopes to take advantage of the elevator and better viewing of the papilla. However, in a prospective randomized study of 45 patients in Korea, no difference was noted between side-viewing and end-viewing endoscopes in success of cannulation and sphincterotomy.2 In fact, end-viewing endoscopes were safer to use. Regardless of what endoscope is used, Billroth II ERCP is one of the more difficult procedures. In a study involving 185 Billroth II ERCP procedures, the failure rate was 34%.3

There is no definite way to correctly identify the afferent lumen to pass the endoscope, although there is the common impression that it comes off the more awkwardly located orifice. The afferent limb can be attached to the stomach along either the lesser (antiperistaltic) (Fig. 29.2, A) or greater (isoperistaltic) curvature (Fig. 29.2, B). Scope passage with an end-viewing device is rather intuitive, and the major challenge is in visualizing and cannulating the papilla. Even though the limited studies did not identify any difference in technical success between side-viewing and end-viewing endoscopies, the reality is that it is far easier to perform cannulation and therapies with the duodenoscopes.

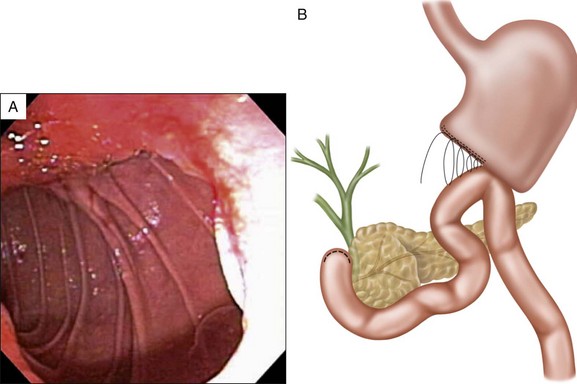

When using a duodenoscope, the difficulty starts with gaining entry into the afferent lumen. It is even more difficult if the afferent limb is sutured to the lesser curvature after it has exited the gastrojejunostomy, as this form of operation creates a fixed and significantly angulated point of entry (Fig. 29.3).4 When a duodenoscope is used, the technique to enter the gastrojejunostomy orifice is the same as for the pylorus. When the lumen can be visualized only in the retroflexed position, gliding the scope along gently toward it rarely works. Suctioning out excess gastric air may make the gliding a little easier. Once the tip of the scope has reached the orifice, the scope should be gradually pulled back and straightened in order to advance further. There is also the technique of entering the lumen by rotating the scope 180 degrees at the orifice and pointing the tip of the scope down until the small bowel lumen is clearly in sight. This technique can theoretically be done with the scope facing the opening rather than “backing in.” However, the endoscope would be blinded by mucosal lining, and visual inspection during the maneuvering would become more difficult. Hand compression of the mid-abdomen or extending a polypectomy snare into the intended lumen has been reported to add to the success of intubation of a difficult intestinal orifice.4 Passage of the duodenoscope alongside or over a stiff guidewire that has been placed with an end-viewing endoscope may assist in entering the correct gastrojejunostomy lumen. Even in a tertiary biliary center, failure to enter the afferent limb has been reported to be as high as 10%.3

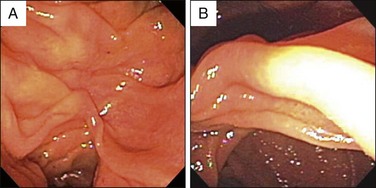

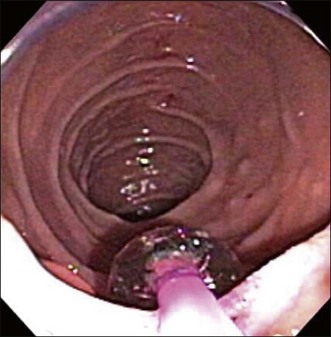

Once the side-viewing duodenoscope has securely engaged in a jejunal lumen, passage forward is safe and effective by constantly orientating the bowel in the 6 o’clock position (Fig. 29.4, A). This would simulate the view of driving a car in a long tunnel. It is common to see two lumens when a duodenoscope is partially retroflexed and it creates confusion regarding where to advance the endoscope. A good rule of thumb is to orientate the two lumens along the vertical midline; the lower lumen is the one that the endoscope should enter (Fig. 29.4, B). Natural intestinal redundancy and tortuosity rarely allow unimpeded forward advancement. Rather, successful passages require a combination of gentle rotation, dial redirection, pulling, and pushing. Care must be taken to minimize sudden or forceful manipulations, as perforation may result. In one series perforation occurred in 5% of cases and was mainly the result of manipulations in the afferent limb.3 In another study 18% of cases encountered jejunal perforation.2 Use of a small caliber and soft, older duodenoscope may reduce the chance of traumatizing the intestinal wall. Minimizing air insufflation helps keep the lumen straight and the bowel wall soft and stretchable. Rotating the patient is occasionally effective in getting around seemingly improbable turns. These measures all may contribute to a safe and successful procedure. With experience and special care, an acceptable risk of perforation can be achieved.5 After passing some distance, it is wise to take a fluoroscopic picture to confirm that the scope has passed or is passing though the transverse duodenum (Fig. 29.5). If the tip of the scope is in the pelvis, it is likely in the efferent limb and should be withdrawn to search for the other intestinal orifice. Some afferent limbs seem to be longer and more tortuous to reach the papilla than others. This impression is indeed correct, as the afferent loop may be created in the antecolic fashion over the transverse colon (Fig. 29.6).

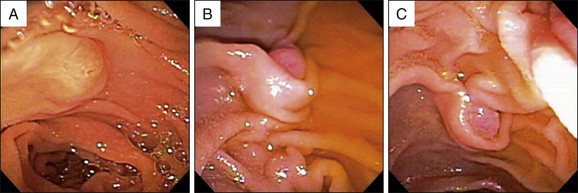

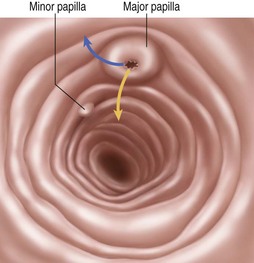

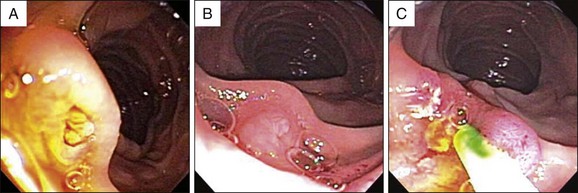

On the way to the proximal duodenum, an anastomosis that connects the afferent and efferent limbs may be encountered. This “Braun procedure” is a modification of the Billroth II operation to reduce bile reflux into the stomach or to lessen the chance of duodenal obstruction (Fig. 29.7). It should not influence the endoscopic passage other than creating confusion for the endoscopist. On some occasions the duodenal stump, which appears as a blind sac with a distinctly flat and smooth mucosa, is reached without the major papilla being noticed. The minor and then major papilla should be readily identified upon gradual withdrawal of the endoscope (Fig. 29.8).

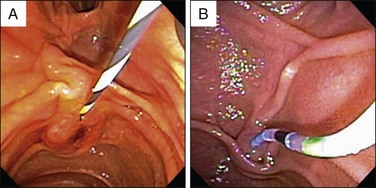

The major papilla is almost always found near the 12 o’clock position of the duodenum when a duodenoscope is used (Fig. 29.8, C). If the intestinal lumen is kept in view ahead of the endoscope, the bile duct is leading away from the endoscope straight ahead or slightly to the right (Figs. 29.9, A, and 29.10). To keep the cannulating catheter or guidewire tangentially along the duodenal wall for biliary access, the papilla should not be approached up close (Fig. 29.8, C). Rather, the scope should be pulled back slightly with its elevator partially lowered for catheter passage. Conversely, the pancreatic duct is easier to cannulate by advancing the scope close to the papilla and keeping the elevator in a lifted position (Fig. 29.8, B). Some endoscopists prefer to use straight-tip catheters for biliary cannulation,5 while others like to use straight guidewires. However, perhaps the most effective way to enter the bile duct is to use a catheter that has been bent in an S-shape (Fig. 29.9, B). A cap-assisted approach has been described to improve cannulation of a Billroth II papilla when an end-viewing endoscope is used (Fig. 29.11).6 On some occasions when pancreas divisum is suspected, the minor papilla should be correctly identified for cannulation. As a general rule, it is located slightly further away from (cephalad to) and to the left of the major papilla (Figs. 29.8, A, and 29.10).

Biliary sphincterotomy is accomplished by the use of either a Billroth II sphincterotome or a needle knife to cut over a biliary stent. A Billroth II push-type sphincterotome is designed virtually opposite to a conventional traction sphincterotome. The cutting wire is loosened to form a half loop over a straight sphincterotome catheter. The sphincterotome with this protruding wire is then pushed forward, over a guidewire, to cut the papilla hood along the 6 o’clock position of the superiorly located papilla. Sphincterotomy done in this manner is slightly less well controlled than in the normal setting because of the pushing motion and suboptimal visualization of the proximal edge of the papillary mound. A modified sphincterotome that forces its tip into an S-shape when the cutting wire tightens may also be used to perform sphincterotomy in this setting.7 However, most endoscopists seem to prefer needle-knife sphincterotomy over a biliary stent because it avoids injury to the pancreatic sphincter and allows a gradual, unhurried tissue cutting.4,8 Balloon sphincter dilation, commonly done with an 8-mm balloon, is technically easy to perform. A randomized study showed that balloon sphincter dilation was as effective as sphincterotomy in facilitating stone extraction, with fewer adverse events, in the Billroth II setting.9 Additionally, there was no more pancreatitis with this form of treatment than with sphincterotomy.

Roux-en-Y Gastrectomy

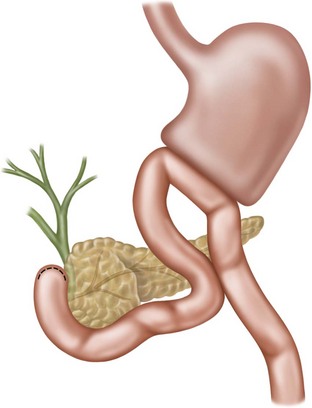

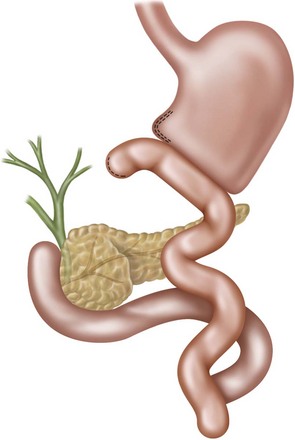

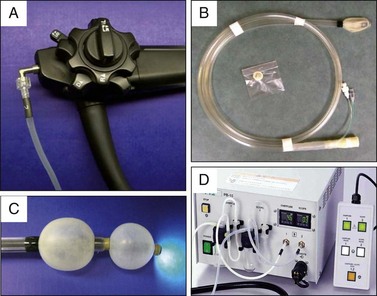

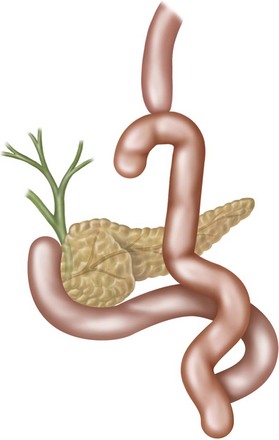

Aimed to reduce reflux of pancreatic and biliary fluids into the stomach following a partial gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y gastrectomy creates a gastric outlet that appears similar to that of a Billroth II surgery. However, this end-to-side anastomosis leads to a very short blind stump and a long Roux limb (Fig. 29.12). The Roux limb extends around 40 cm before a jejunojejunostomy anastomosis is found. At this point two or three lumens (Fig. 29.13, A and B) will be identified, depending on whether the two jejunal limbs are connected end-to-side (Fig. 29.13, C) or side-to-side (Fig. 29.13, D). If done side-to-side, one of the three outlets is a short, blind stump. If the afferent limb is correctly entered, the endoscope will travel up the proximal jejunum, the ligament of Treitz, the transverse duodenum, and finally the descending duodenum. This long distance to travel makes it nearly impossible for a 125-cm–long duodenoscope to reach the major papilla. Many longer length endoscopes have been used to perform ERCP in this setting, including pediatric or adult versions of colonoscopes and push enteroscopes.9 A special oblique-viewing endoscope has been reported to be potentially useful for this purpose.10 Double-balloon enteroscopes, which can reach as far as the cecum perorally, were introduced to the United States in 2004 (Fig. 29.14). Their use in performing diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP in patients with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy was soon reported.11 To date all forms of deep enteroscopies, including single and spiral enteroscopies, are routinely used for a variety of pancreatic and biliary conditions in this setting.

The challenge of performing ERCP in a Roux-en-Y gastrectomy lies not just in traveling a great length and recognizing the proper intestinal lumen but also in selectively cannulating the bile duct and pancreatic duct. It is not uncommon to drive the scope right past the anastomosis into the efferent jejunal limb without recognizing the jejunojejunostomy. A clue to the vicinity of the anastomosis is the presence of bile fluid. Once bile is seen, scope advancement should be slowed down to look for the luminal bifurcation. The afferent limb is always found across the circular rim of anastomosis. Interestingly, it is typically the straighter lumen of the two. All end-viewing endoscopes have the inherent difficulty in visualizing the major papilla because of its location along the interior aspect of the duodenal C-loop. Even when it is identified, cannulation is extraordinarily difficult because of awkward orientations and unstable positioning for cannulation (Fig. 29.15). In the hands of ERCP experts, the success rate is a mere 67%.12 Iwamoto and colleagues reported the success of performing diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP with a double-balloon enteroscope in six patients.12 Interestingly, the authors fitted a small plastic cap on the tip of the enteroscope to enable them to do the cannulations. It is uncertain if and how this plastic cap helps with the procedure. Given the difficulty and frequent failure of performing ERCP in this postoperative anatomy, it is best to refer this type of case to a tertiary biliary center or to choose an alternative method such as a transhepatic study. Performing ERCP with the intent to evaluate and treat a pancreatic condition is particularly problematic, as a transhepatic procedure cannot intubate the pancreatic duct. We prefer to use a long length (320 cm) 5 Fr diagnostic ERCP catheter preloaded with a hydrophilic guidewire to perform the cannulation, if a double- or single-balloon enteroscope is employed. Contrast can be injected with this setup if a Y-adapter is used (Fig. 29.15, C). An intraoperative transjejunal ERCP method has been reported to overcome this difficulty. At laparotomy, an enterotomy is made at 20 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz to allow passage of a gas-sterilized duodenoscope to advance up the afferent limb.13

Total Gastrectomy

Done usually for treatment of gastric cancer or postoperative adverse events, a total gastrectomy necessitates the creation of an end-to-side esophagojejunostomy. One lumen of the esophagojejunostomy is a blind end, whereas the other is the jejunal Roux limb (Fig. 29.16). A short distance down this limb is a side-to-side or end-to-side jejunojejunostomy to receive pancreatic and biliary contents. Similar to the Roux-en-Y gastrectomy, the endoscope has to enter the afferent limb and pass through the proximal jejunum and most of the duodenum. But unlike Roux-en-Y partial gastrectomy, a duodenoscope actually can reach the major papilla on a more regular basis perhaps because of its straighter and shorter upper GI route. Once the major papilla is identified with the duodenoscope, the approach to ERCP cannulation and therapy is quite similar to that for a Billroth II anatomy. But if a duodenoscope is too short to reach the descending duodenum, then an end-viewing long endoscope has to be used. In that case, the challenge lies in cannulating and treating disease processes without the benefits of an elevator and the side-viewing capability. The same techniques used for a Roux-en-Y gastrectomy apply to this situation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree