Chapter 27 ERCP in Children

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was introduced into pediatric medicine in the mid to late 1970s following initial experience in adult patients.1 It is now routinely used for the diagnosis and treatment of biliary tract and pancreatic diseases in children who are referred to major medical centers worldwide.2–9 Although technical expertise remains concentrated among endoscopists trained in adult medicine, pediatric specialists routinely collaborate closely in patient selection and pre- and postprocedural management.10 In high volume tertiary pediatric referral centers, ERCP is sometimes performed by expert pediatric endoscopists working alone or in concert with adult medicine endoscopists.

Description of Technique (Box 27.1)

Procedure Setting

Box 27.1

Key Points

Pediatric emergency equipment and subspecialists should be immediately available to manage adverse events.

Pediatric emergency equipment and subspecialists should be immediately available to manage adverse events.

The endoscopist should be familiar with pediatric pathology or consult a pediatric specialist and have technical ability to proceed with therapeutic intervention.

The endoscopist should be familiar with pediatric pathology or consult a pediatric specialist and have technical ability to proceed with therapeutic intervention.

General anesthesia is required for the majority of young children.

General anesthesia is required for the majority of young children.

Fluoroscopic equipment should be adjusted for children to minimize radiation exposure.

Fluoroscopic equipment should be adjusted for children to minimize radiation exposure.

Ultraslim diameter duodenoscope is required for infants <12 months of age.

Ultraslim diameter duodenoscope is required for infants <12 months of age.

Endoscopist

Therapeutic ERCP requires that an endoscopist achieve selective deep cannulation of the desired (biliary or pancreatic) duct with greater than 90% success to enable the essential interventions of dilation, stent placement, sphincterotomy, and stone extraction. Since experience with more than 200 cases is required by the average trainee to achieve this rate of technical success11 and the volume of pediatric cases is relatively small even in tertiary care facilities, pediatric specialists will require either supplemental training with adult patients or a very long training period to achieve initial competence. The volume of cases required to maintain competence remains controversial and will vary by endoscopist and by complexity of procedures.12 Adverse event rates have been shown to correlate with case volume for both endoscopist and facility.13,14 High ERCP volume and advanced endoscopic skills reside most often within adult medicine centers of excellence, and technical success is certainly required for optimal outcomes. Yet children may have limited access to these centers. Endoscopists must consider these factors and the availability of alternative management options before embarking on ERCP in pediatric patients.

Fluoroscopy

Fluoroscopy for pediatric ERCP may be performed using a fixed table in a dedicated fluoroscopy suite or a portable C-arm in a separate procedure room. The advantages of the C-arm device are portability, lower cost, and easier oblique imaging. Modern digital devices provide excellent image quality. The x-ray equipment should be adjusted to accommodate the smaller body of a young child and reduce the radiation dose rate. Shielding of reproductive organs is important and should be performed in all patients. Good fluoroscopic technique by the examiner can minimize radiation exposure to the child and to personnel (see also Chapter 3). The following rules or principles will help advance this goal: (1) Position the child so that the beam takes the shortest distance through the body—i.e., avoid unnecessary oblique projection; (2) position the image intensifier or receptor above the patient; (3) minimize the distance of the intensifier and maximize the distance of the x-ray tube to the child’s body; (4) use the least magnification necessary and use field collimators to focus on areas of interest; (5) avoid the use of a grid; and (6) minimize beam-on time and use the slowest pulse rates that produce acceptable imaging for a given task. The assistance of a radiation technologist with pediatric experience for equipment setup and the availability of a radiologist with pediatric training for consultation can be very important in achieving the goals outlined above. Either low osmolar, nonionic or high osmolar, water-soluble contrast media in the range of 150 to 300 mg/mL may be used.

Endoscopic Equipment

Neonates and infants require a small diameter instrument in the range of 7 to 8 mm that will pass easily through the pylorus and allow effective positioning of the tip adjacent to the major papilla. Currently, there is only one commercially available duodenoscope that is suitable for use in small infants, the PJF 160 (Olympus America, Inc., Lehigh Valley, Pa.). This endoscope has a maximum distal tip diameter of 7.5 mm, an operating channel diameter of 2.0 mm, and an elevator. Basic diagnostic and therapeutic maneuvers are possible with this endoscope, although the repertoire of available accessories that will fit through the small operating channel is somewhat limited. Catheter tips that taper to a diameter of 3 to 4 Fr are helpful in order to selectively cannulate biliary and pancreatic ducts in infants. However, deep advancement of catheters into normal ducts is not always possible in young infants due to the fine caliber of these structures at this age (Fig. 27.1). An ultratapered (3.5 Fr) cannula, a retrieval balloon catheter, and a wire basket catheter that will fit the 2.0 mm channel of the PJF 160 duodenoscope are available from Olympus. Other highly tapered cannulas such as the precurved Glo-Tip, GT-5-4-3 (Cook Endoscopy, Winston-Salem, N.C.) may be used. A tapered-tip sphincterotome catheter with a short cutting wire such as the UTS-15 (Cook Endoscopy) can be advanced with some resistance through the operating channel of the PJF 160 endoscope.

Technique

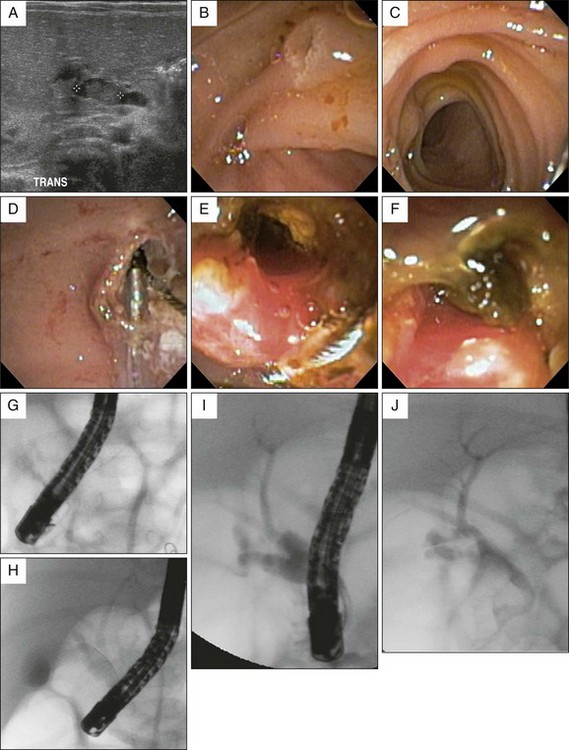

The techniques for ERCP in children are the same as for adult patients. The procedure can be conducted with the child either prone or supine on the examining table, although prone positioning is most comfortable for the endoscopist. The basic endoscopic maneuvers are more technically challenging in children because side-viewing endoscopes and accessories have not been optimally designed to work in a narrow lumen and through a narrow operating channel, respectively. In small children and infants the endoscope tip is forced into a position in close proximity to the papilla, allowing very little of the cannula to extend out into view and increasing the difficulty of achieving optimal position for selective bile duct cannulation. Although precurved cannulas are available, selective biliary cannulation is most easily achieved using a tapered tip, pull-type sphincterotome with a short cutting wire. Tightening the cutting wire increases angulation of the catheter tip within a short working distance from the papilla. Also, by starting the procedure with a sphincterotome, the endoscopist can proceed directly with therapy when indicated. Wire-guided access, using a soft-tipped, hydrophilic, narrow gauge wire, may be used if free cannulation proves too difficult (Fig. 27.1). Stiff catheters such as those used for stricture dilation or stone retrieval are more likely to require wire-guided entry. Also, in young infants a soft-wire retrieval basket will enter the duct more easily if partially opened since the basket wires are more flexible when extending from the stiffer plastic sheath. Alternatively, the endoscope can be placed in the long position, which may achieve a more favorable position in front of the major papilla, similar to the technique used for cannulation of the minor papilla. However, tip control is not optimal with the endoscope in this position. Sphincterotomy, stone extraction, and temporary stent placement have all been successfully performed in very young infants using small diameter endoscopes (Fig. 27.2).15–20

Indications and Contraindications (Box 27.2)

Biliary Indications

Neonatal Cholestasis

Neonatal cholestasis is the only biliary condition unique to pediatrics in which purely diagnostic cholangiography has a role. The most common causes of neonatal cholestasis are idiopathic neonatal hepatitis and total parenteral nutrition, both of which are frequently encountered in neonates compromised by premature birth, congenital abnormalities requiring surgical intervention, or other acute illnesses of the newborn. These conditions are characterized by hepatocellular and canalicular dysfunction rather than bile duct obstruction. However, they can sometimes be difficult to distinguish from ductal obstruction due to inspissated bile (seen with cystic fibrosis or idiopathic causes), bile duct paucity (e.g., Alagille syndrome), or obliteration of the duct due to biliary atresia (BA). Of these conditions, the correct diagnosis is most urgently needed for BA since surgical intervention by portoenterostomy (Kasai procedure) substantially reduces long-term morbidity and mortality if undertaken during the early weeks and months of life.21,22 If left untreated, BA leads to liver failure and organ transplantation or death by 1 to 2 years of age.

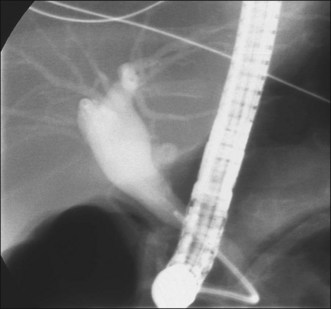

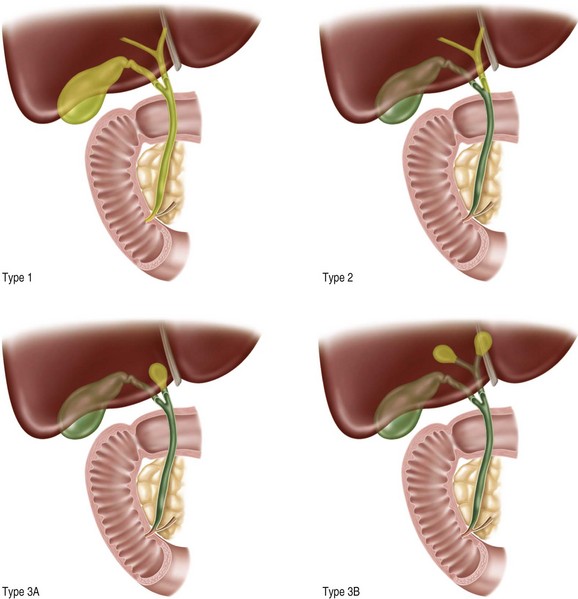

The role of ERCP in the diagnosis of BA remains controversial due to variations in clinical practice; interpretation of liver histology; access to high-quality diagnostic ultrasound, MRI, and scintigraphy imaging; and availability of highly skilled biliary endoscopists. Most pediatric gastroenterologists, hepatologists, and surgeons continue to rely on a combination of clinical presentation, serum chemistry profile, ultrasonography, biliary scintigraphy, and liver histology rather than ERCP to identify infants in need of surgical exploration, intraoperative cholangiography, and possible portoenterostomy. However, published series of ERCP in infants with unexplained cholestasis consistently report high positive and negative predictive values exceeding 90% with only rare minor adverse events.23–27 A high level of skill and confidence in technical proficiency is required by endoscopists who use ERCP for this indication. The endoscopic findings that suggest BA include absence of visible bile within the duodenum, partial filling of the bile duct with abnormal termination, and failure to fill the bile duct despite filling of the pancreatic duct (Fig. 27.3).28 Complete filling of the bile duct including hepatic branches excludes the diagnosis of BA. ERCP is most helpful when the diagnosis of BA is unlikely but cannot be definitely excluded without cholangiography. In this situation, an unnecessary exploratory laparotomy can be avoided by demonstrating a patent bile duct (Fig. 27.4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree