Chapter 42 ERCP for Acute and Chronic Adverse Events of Pancreatic Surgery and Pancreatic Trauma

Chronic pancreatitis, cystic neoplasms, and suspected or established malignancy are the main indications for pancreatic surgery. The various types of pancreatic surgeries are outlined in Box 42.1. This chapter focuses on types of pancreatic surgeries, their associated adverse events, and the role of endoscopy in management of adverse events. Finally, we highlight the role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in the treatment of pancreatic trauma. ERCP in postsurgical anatomy is also addressed in Chapter 29.

Box 42.1

Types of Pancreatic Surgeries

Classic Whipple operation (pancreaticoduodenectomy with antrectomy)

Classic Whipple operation (pancreaticoduodenectomy with antrectomy)

Modified Whipple (pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy)

Modified Whipple (pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy)

Puestow procedure (longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy)

Puestow procedure (longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy)

Beger procedure (duodenal-preserving pancreatic head resection)

Beger procedure (duodenal-preserving pancreatic head resection)

Frey procedure (duodenal-preserving pancreatic head resection with lateral pancreaticojejunostomy)

Frey procedure (duodenal-preserving pancreatic head resection with lateral pancreaticojejunostomy)

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple Operation) with and without Pylorus Preservation

Anatomy

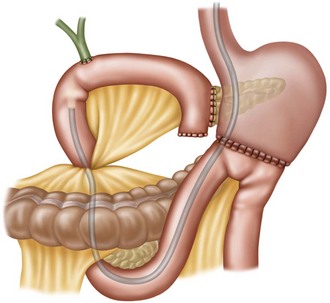

The classic Whipple operation involves removal of pancreatic head, pancreatic neck, gastric antrum, duodenum, 20 cm of proximal jejunum, gallbladder (if present), distal common bile duct, and regional lymph nodes. There are two side-to-side enteroenterostomies visible from the gastric remnant (Fig. 42.1). The afferent limb, which is usually 40 to 60 cm long, ascends superiorly and ends blindly with an end-to-end or end-to-side pancreaticojejunostomy. An end-to-side choledochojejunostomy is usually located 10 cm proximal to the end of the afferent limb and is located along the antimesenteric border, often behind a mucosal fold.

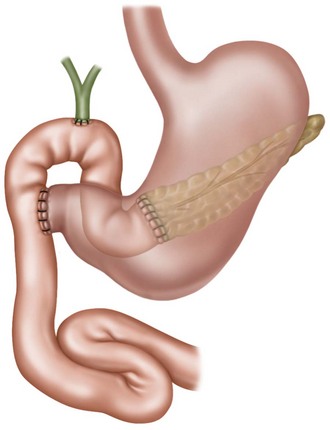

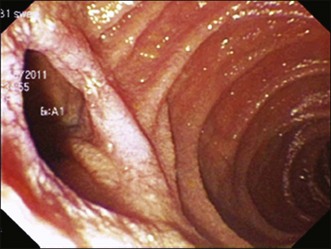

Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (modified Whipple) is performed to prevent delayed gastric emptying. The entire stomach is preserved and the bulk of the duodenal bulb remains (Fig. 42.2). Upon exiting the stomach, a duodenal stump is encountered with two end-to-side enteroenterostomies, with one leading to the afferent limb containing the biliary and pancreatic anastomoses (Fig. 42.3). The location of the afferent limb within the visual field is not uniform and also is dependent on the type of endoscope used (side-viewing versus forward-viewing).

Role of Endoscopy in the Management of Adverse Events

Endoscopy plays a very limited role in the management of acute postoperative adverse events following Whipple surgery. Pancreatic leaks, although reported to occur in up to 20% of Whipple surgeries, are managed by percutaneous drainage, administration of octreotide, and intravenous hyperalimentation. However, endoscopy plays a significant role in the management of delayed pancreaticobiliary strictures and/or stones (Box 42.2). The decision about the necessity of endoscopic intervention is made with the aid of abdominal computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) with or without secretin.

Box 42.2

Adverse Events of Pancreaticoduodenectomy and Pylorus-Preserving Pancreaticoduodenectomy

Prior to embarking on endoscopy, it is imperative to plan, which includes choice of endoscope, accessories, patient position, and need for anesthesia support, so that optimal outcomes can be achieved in this subset of patients (Box 42.3; see also Chapter 9).

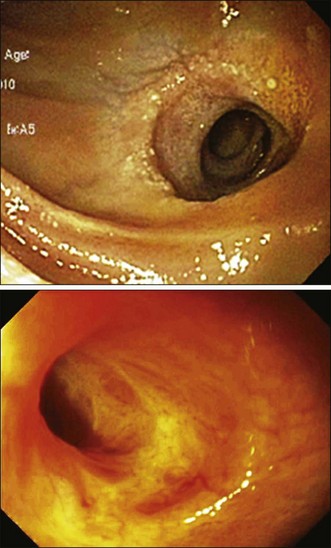

In classic Whipple surgery, the biliary anastomosis may be reached with a standard duodenoscope. The side-viewing endoscope offers technical advantages of an en face view of the anastomosis and presence of an elevator to assist in control of accessories. However, the success rate in accessing the pancreatic anastomosis is suboptimal at best.1A widely patent anastomosis is seen in Fig. 42.4.

Not uncommonly, the approach using a side-viewing endoscope results in failure to reach either the biliary or the pancreatic anastomosis due to the insertion tube length. This is especially true in patients with pylorus-preserving anatomy and longer afferent limbs. In these cases, the procedure may be accomplished with a colonoscope. Therapeutic channel colonoscopes allow placement of 10 Fr plastic biliary stents. Some biliary self-expandable metal stents can be passed through colonoscopes (both pediatric and adult).2 However, absence of an elevator makes it challenging to maneuver the accessories and accomplish therapeutic intervention. To circumvent this drawback, a prototype oblique-viewing endoscope with an elevator has been used.

Various other techniques can be employed to gain access to the end of the afferent limb and the biliopancreatic anastomoses (Box 42.4).

Box 42.4

Techniques to Facilitate Access to the Afferent Limb and the Biliary and Pancreatic Anastomoses

Manual application of extracorporeal pressure

Manual application of extracorporeal pressure

Interpretation of air cholangiograms

Interpretation of air cholangiograms

Secretin provocation for identification of the pancreatic anastomosis

Secretin provocation for identification of the pancreatic anastomosis

Choice of accessories, including ultratapered catheters, straight and angled wires

Choice of accessories, including ultratapered catheters, straight and angled wires

Head-down patient position with injection of contrast into the afferent limb when the choledochojejunostomy and pancreaticojejunostomy cannot be reached

Head-down patient position with injection of contrast into the afferent limb when the choledochojejunostomy and pancreaticojejunostomy cannot be reached

There are limited but increasing data on the use of single-balloon enteroscopes (SBE)3,4 and double-balloon enteroscopes (DBE)5 in achieving technical success in accessing biliary and pancreatic anastomoses. These procedures are performed by experienced endoscopists at tertiary care centers when ERCP failure is due to inability to reach the anastomosis with standard endoscopes. Balloon-assisted ERCP is often time consuming and difficult due to the limited availability of compatible accessories.

Biliary Obstruction

Bilioenteric Anastomotic Stricture

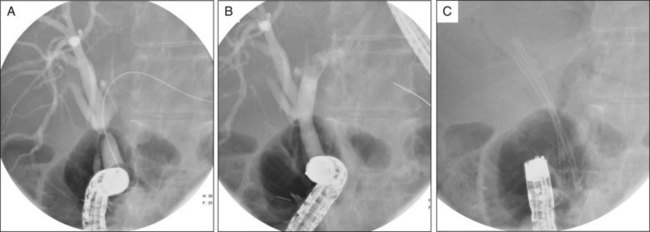

Bilioenteric anastomotic strictures can be benign or malignant due to recurrent disease such as pancreatic cancer, primary sclerosing cholangitis, or autoimmune disease. Distinguishing between the two can be extremely difficult due to submucosal tumor invasion. Treatment of these strictures is undertaken as for other benign (Fig. 42.5) and malignant strictures, although the options can be limited by the endoscope length and channel diameter. In some cases, needle-knife entry can be undertaken, though this carries risk of perforation (Video 42.1).

Afferent Limb Obstruction

Afferent limb obstruction is often due to recurrent tumor, usually occurring at the ligament of Treitz, but can also occur from radiation therapy. Such downstream obstruction most commonly presents with obstructive jaundice or cholangitis. Other presenting symptoms include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. The most common endoscopic findings are malignant or benign luminal stricturing of the afferent limb, severe angulation of or fixed afferent limb, and mucosal changes of friability, ulceration, and telangiectasia from radiation enteropathy. Endoscopic interventions performed for management include placement of plastic and self-expandable metal stents in the afferent limb and/or obstructed bile duct (Video 42.2).6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree