Enucleation of a Pancreatic Tumor

Henry A. Pitt

Introduction

Over the past four decades, the mortality of pancreatic resection has improved significantly at high-volume centers. As a result, the most common procedures performed for small neuroendocrine and cystic tumors of the pancreas are pancreatoduodenectomy and distal pancreatectomy. However, the short- and long-term morbidity of a major pancreatic resection remains high. Thus, debate continues as to whether small benign and premalignant lesions of the pancreas should be observed or resected. In comparison, enucleation is a low-risk procedure that preserves pancreatic parenchyma and function. Thus, pancreatic enucleation may be an underutilized procedure that should be considered for small, frequently asymptomatic, pancreatic lesions that, if observed, have the potential to grow and metastasize.

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

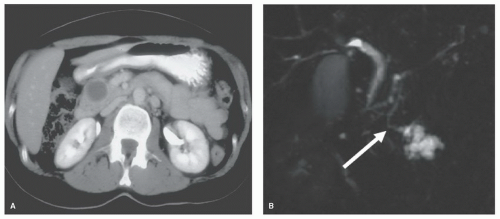

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONSThe relative indications for and contraindications against pancreatic enucleation are presented in Table 9.1. The most frequent indication for pancreatic enucleation is a neuroendocrine tumor. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) that are small with a low Ki67 and/or mitotic index have a low potential for spread and, therefore, are an appropriate indication for enucleation (Fig. 9.1A). However, considerable debate exists regarding what represents a “small” PNET. In a recent analysis of well to moderately differentiated PNETs LaRosa and colleagues determined that 3 cm provided the best discriminative power for a size cutoff. Both Lee et al. and Pitt and associates also used 3 cm as the size limit in their analyses.

In addition to size, other considerations in PNETs include whether the tumor is (a) functioning or nonfunctioning, (b) sporadic or part of a multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome, (c) solitary or multiple and/or (d) isolated or associated with liver metastases. In general, functioning tumors present when they are smaller and, therefore, may be more amenable to enucleation. Similarly, sporadic, solitary, nonmetastatic tumors may be more appropriate for enucleation. However, enucleation also may be reasonable if the primary tumor is small, and the patient has multiple liver metastases that are not

amenable to resection and/or ablation. Since the Ki67 and/or mitotic index usually are not known at the time of surgery, one strategy that may be employed intraoperatively is sentinel lymph node removal. If a lymph node metastasis is found, enucleation may be abandoned in favor of resection with local lymph node dissection.

amenable to resection and/or ablation. Since the Ki67 and/or mitotic index usually are not known at the time of surgery, one strategy that may be employed intraoperatively is sentinel lymph node removal. If a lymph node metastasis is found, enucleation may be abandoned in favor of resection with local lymph node dissection.

TABLE 9.1 Indications and Contraindications for Pancreatic Enucleation | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

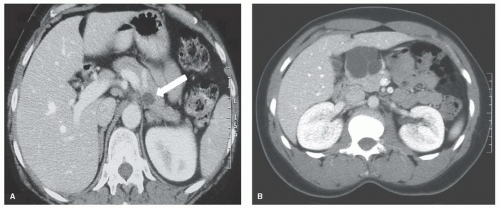

In a recent analysis from Indiana University side-branch intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) were the second most common indication for enucleation (Fig. 9.1B). However, because of the increased risk of carcinoma in situ or invasive cancer in main duct IPMNs, enucleation should not be undertaken in patients with mixed IPMNs which involve both the main duct and side branches. Enucleation also should be considered in patients with small mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs) (Fig. 9.2A). On the other hand, enucleation is not an adequate operation for mucinous cystadenocarcinomas.

Debate also continues regarding whether serous cystadenomas (SCAs) should be observed or removed. SCAs (Fig. 9.2B) have negligible malignant potential and generally grow slowly. However, enucleation is usually straight forward when SCAs are small. On the other hand, if a SCA is allowed to grow, resection in an otherwise normal pancreas

may be the only option but is associated with increased short- and long-term morbidity. At the other end of the spectrum, enucleation is not an appropriate operation for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPNs) lymphoepithelial cysts and lymphangiomas also may be adequately removed by enucleation. However, for all of the pancreatic lesions that may be enucleated, proximity to the main pancreatic duct as well as placement in the pancreatic tail are relative contraindications.

may be the only option but is associated with increased short- and long-term morbidity. At the other end of the spectrum, enucleation is not an appropriate operation for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPNs) lymphoepithelial cysts and lymphangiomas also may be adequately removed by enucleation. However, for all of the pancreatic lesions that may be enucleated, proximity to the main pancreatic duct as well as placement in the pancreatic tail are relative contraindications.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNINGThe most common pancreatic lesions that may be enucleated are small, functioning neuroendocrine tumors. The diagnosis of insulinoma, gastrinoma, vasoactive intestinal peptide producing tumor (VI Poma) and glucagonoma may be established with a careful history, physical examination (for the rash with glucagonoma) and appropriate laboratory studies. For nonfunctioning PNETs, a serum chromogranin A also may be elevated. For the remaining lesions where enucleation may be indicated, no serum markers are available (Table 9.1).

A pancreatic lesion that may result in enucleation is most often discovered on a computerized tomography (CT) of the abdomen (Fig. 9.2). This study may be performed for vague symptoms, usually pain, or for other reasons such as an evaluation for kidney stones. As concern increases for the over exposure to radiation with repeated CT scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) also is detecting more small pancreatic lesions. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) also may be more sensitive than CT at detecting small cystic pancreatic tumors. In addition to CT and MRI, percutaneous ultrasound (US) may detect small pancreatic lesions, but percutaneous US is not as sensitive as CT and MR.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with fine needle aspiration (FNA) for cytology, the presence of mucin, amylase, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and chromogranin A (CGA) is being performed more frequently to decide whether to observe or to operate. However, the accuracy of CT, MRI or EUS, even with FNA, is at best 75% to 85% in establishing a correct diagnosis. All of these imaging modalities are able to accurately locate the lesion within the pancreas. However, MRCP may be the best at demonstrating the relationship between the lesion and the main pancreatic duct as well as the communicating duct in side-branch IPMNs (Fig. 9.1B).

The remainder of the preoperative preparation for pancreatic enucleation does not differ significantly from other pancreatic surgery. Evaluation of the patient’s general health, including cardiopulmonary, renal and hepatic function is indicated. However, the relative risk to life is significantly less for enucleation than for pancreatic resection. Data from the American College of Surgeons—National Surgical Quality Improvement Program suggest that the relative risk of mortality following enucleation is one-sixth that of distal pancreatectomy and one-tenth of pancreatoduodenectomy. Thus, the decision to operate in elderly patients with comorbidities may favor surgery if enucleation is the planned operation. Blood loss is less with enucleation than with resection, and the need for a blood transfusion is unlikely. Nevertheless, typing and cross matching blood is reasonable. Pancreatic enucleation is a “clean” operation so preoperative administration of a first generation cephalosporin is adequate antibiotic prophylaxis. As the operative time for enucleation is less than for resection antibiotic redosing intraoperatively usually is not necessary.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

SURGICAL TECHNIQUEThe first decision is whether to perform the operation minimally invasively or open. This choice will be based on surgeon expertise, patient preference and location of the lesion. For potentially malignant lesions, the first step is to examine the peritoneum and surface of the liver for metastases. If none are found, ultrasound of the liver also should be performed. Again, in the absence of metastatic disease, the next step is to widely expose the pancreas. In general, tumors and/or cysts that are anterior to the pancreas will be more amenable to enucleation. However, lesions that lie posteriorly in the head and/or uncinate can be enucleated but an extensive Kocher maneuver will be required. Once the lesion has been exposed, intraoperative ultrasound imaging is performed to further assess (a) involvement/relationship to the main pancreatic duct, (b) whether the lesion is cystic or solid, (c) if cystic, whether mural nodules are present, and (d) whether other pancreatic lesions are present. If concern exists that enucleation will result in injury to the main pancreatic duct or if a mural nodule is encountered, resection should be undertaken.

To proceed with enucleation of a deep lesion, the pancreatic parenchyma overlying the tumor or cyst should be carefully opened with small vessels being ligated with fine sutures or cauterized. However, most lesions that are amenable to enucleation are on or close to the surface of the pancreas. As a result, dissection is begun at the edges of the lesion and continues with care being taken to stay close to but not entering the tumor or cyst. For neuroendocrine tumors, staying in the correct plain between the pancreas and the tumor is usually straight forward (Fig. 9.3A). This goal may be somewhat more difficult for mucinous cystic neoplasms (Fig. 9.3B) and for side-branch IPMNs because the wall of the cyst may be quite thin.

When enucleating neuroendocrine tumors, mucinous cystic neoplasms, serous cystadenomas, solid pseudopapillary neoplasms and lymphangiomas, no direct connection exists between the lesion and the pancreatic ductal system. However, when enucleating side-branch intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, a goal is to identify and, when possible, ligate the communicating duct (Fig. 9.4). In general, frozen section is performed to (a) make a final diagnosis and (b) for cystic lesions, to be sure that no carcinoma in situ or invasive cancer is present. However, the likelihood of discovering cancer at this stage is extremely low as the presence of invasion will generally preclude enucleation. For neuroendocrine tumors, injection of 1 or 2 ml of methylene blue dye into the cavity to determine the location of sentinel node(s) may be appropriate.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree