Fig. 11.1

Schematic representation of the major variants of type-0 neoplastic lesions of the digestive tract: polypoid (Ip and Is), nonpolypoid (IIa, IIb, and IIc), nonpolypoid and excavated (III). (From [13]. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier Limited)

Clinical Staging

The patients who are considered for endoscopic resection of gastric cancer should undergo endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), computed tomography, and F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) for clinical staging. Patients with no or low risk of lymph node metastasis are ideal candidates for endoscopic resection .

In a recent meta-analysis including 22 studies, Cardoso and colleagues reported that the accuracy of EUS for T staging was 75 %, and EUS was most accurate for T3 tumors, followed by T4, T1, and T2. In addition, the accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of EUS for N staging were 64, 74, and 80 %, respectively [16]. Also, studies have reported that the reliability of EUS to evaluate the depth of T1 tumor invasion remains insufficient even with a high-frequency probe (12–20 MHz) [17, 18]. Based on these findings, EUS is not accurate enough to determine the depth of tumor especially for the patient with superficial lesions. Thus, the major role of EUS is to exclude obvious lymph node involvement.

On the other hand, previous studies have shown that the specificity of FDG-PET to detect lymph node involvement and distant metastasis was high (89–100 and 35–74 %, respectively), whereas the sensitivity was varied (21–40 and 35–74 %, respectively) [19–21]. Koga et al. have demonstrated that physiological FDG uptake in stomach varies depending on the location of stomach [22]. Other studies have reported that the FDG uptake is low in the early gastric cancer as well as signet-ring cell carcinoma and poorly differentiated carcinoma [23, 24]. Therefore, the major role of FDG-PET in gastric cancer is to evaluate for distant metastasis.

Because T staging is limited using EUS and FDG-PET, the final staging can only be done through histological analysis. Endoscopic resection is most commonly used for the purpose of T staging. To assess the relationship between depth of invasion and lymph node involvement, the mucosal and submucosal layers have been subdivided into thirds with each third going deeper into gastric wall. Intramucosal (m) and submucosal (sm) cancers have a total of six different layers of invasion: m1–m3 (m1 is limited to the epithelial layer; m2 invades into the lamina propria; m3 invades into but not through the muscularis mucosa) and sm1–sm3 (thirds of the submucosa) (Fig. 11.2) .

Fig. 11.2

Subdivision of the mucosa and submucosa. For the staging purpose, the mucosal layers are subdivided into thirds with each third going deeper into the gastric wall. (Modified from Soetikno et al. [30], with permission from American Society of Clinical Oncology)

Indications for Endoscopic Resection

Currently, endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer has been widely accepted and well established in Japan. Initial criteria for endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer were established based on the technical limitations of en bloc endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) for removing neoplastic lesions larger than 20 mm in diameter [11, 25]. Therefore, the present guidelines for indication of EMR are: (1) differentiated (well and/or moderately differentiated and/or papillary adenocarcinoma) histology, (2) no ulcerative findings and a depth of invasion that is confined to the mucosa (T1a), (3) a tumor diameter ≤ 20 mm, and (4) absence of lymphatic-vascular involvement [26]. Endoscopic resection is not indicated for poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma or signet-ring cell carcinoma.

However, clinical observations have suggested that the absolute criteria may be too strict and can lead to unnecessary gastrectomy. To expand the criteria with the establishment of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) technique, Gotoda and colleagues analyzed more than 5000 patients who underwent gastrectomy with meticulous D2 lymphadenectomy to define the risk of lymph node metastasis in specific groups of patients with early gastric cancer [27]. According to the study, there were four subgroups of patients with early gastric cancer with no risk of lymph node metastasis: (1) differentiated (well and/or moderately differentiated and/or papillary adenocarcinoma) intramucosal adenocarcinoma without lymphatic-vascular invasion, regardless of ulceration status and a tumor size < 30 mm (n = 1230; 95 % CI, 0–0.3 %), (2) differentiated intraluminal adenocarcinoma without lymphatic-vascular invasion, without ulceration, regardless of tumor size (n = 929; 95 % CI, 0–0.4 %), (3) undifferentiated (poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and/or signet-ring cell carcinoma) intramucosal adenocarcinoma without lymphatic-vascular invasion, without ulceration, and a tumor size < 30 mm (n = 141; 95 % CI, 0–2.6 %), and (4) differentiated minute submucosal adenocarcinoma (sm1) without lymphatic-vascular invasion, and a tumor size < 30 mm (n = 145; 95 % CI, 0–2.5 %) [27]. Despite these data, endoscopic therapy for patients with undifferentiated intramucosal carcinoma has been considered controversial. However, recent studies have shown that no lymph node metastasis was identified in 310 patients with undifferentiated intramucosal carcinoma without ulceration or lymphatic-vascular invasion, and tumor size < 20 mm (95 % CI, 0–0.96 %) [28, 29], suggesting that early gastric cancer with undifferentiated histology can be included in the spectrum of endoscopic resection. Based on these results, proposed indications for endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer have been expanded to include intramucosal (m1–3) differentiated adenocarcinoma without ulceration regardless of size or with ulceration ≤ 30 mm in diameter, and the superficial third submucosal (sm1) differentiated adenocarcinoma ≤ 30 mm in diameter [30] (Table 11.1). In addition, these tumors should be without lymphatic-vascular involvement .

Table 11.1

Proposed expanded criteria for endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for early gastric cancer

Guideline criteria (EMR) | Proposed expanded criteria (ESD) |

|---|---|

Intramucosal (m) tumor | Intramucosal (m) tumor |

Elevated lesion ≤ 20 mm | Without ulceration > 20 mm |

Flat/depressed lesion ≤ 10 mm without ulceration | With ulceration ≤ 30 mm |

Submucosal (sm1) ≤ 30 mm | |

No indication for submucosal tumor | |

Moderately or well-differentiated adenocarcinoma | |

No lymphatic-vascular invasion | |

Endoscopic Resection Techniques: EMR and ESD

EMR and ESD were established for the minimally invasive endoscopic removal of benign and early malignant lesions in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. EMR is typically used for removal of lesions smaller than 20 mm or piecemeal removal of larger lesions. ESD is utilized for en bloc resection of lesions greater than 20 mm. En bloc resection is ideal because of the higher risk of disease recurrence with piecemeal removal due to incomplete resection and compromised histological assessment secondary to involved radial margins [31].

Endoscopic Mucosal Resection

Several techniques of EMR have been introduced including the injection-assisted technique, the cap resection technique, and the ligate-and-cut technique (Fig. 11.3) .

Fig. 11.3

Four types of commonly used endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) techniques. a The inject-and-cut technique. b The inject-lift-cut technique. c The EMR with cap technique. d The EMR with ligation technique. (From Soetikno et al. [30]. Reprinted with permission from American Society of Clinical Oncology)

Injection-assisted EMR starts with injection of a solution into the submucosal layer under the lesion, creating a “safety cushion.” This cushion lifts the lesion to facilitate its removal and prevent complications such as perforation caused by mechanical and electrocautery damage to deeper layers. A polypectomy snare is used through a single-channel endoscope to snare the lesion (Fig. 11.3a). The injected solutions, especially normal saline, spread out into the submucosal space within a few minutes and repeat injections may be required for successful EMR. In addition, the marking of the target tumor margin using electrocautery may be considered to identify the accurate resection margin after the submucosal injection changes the shape of the lesion.

The strip biopsy technique was developed as an application of injection technique. In this method, a double-channel endoscope is used in order to snare the lesion while it is grabbed and pulled toward the endoscope with a grasper [32] (Fig. 11.3b). As a variation of this technique, Kondo et al. reported EMR of large gastric lesions with countertraction of the lesion by grasping forceps placing through a percutaneous gastrostomy [33].

Currently, the endoscopic cap resection technique (EMR-C) and the endoscopic ligate-and-cut technique (EMR-L) are commonly performed in the USA. Between these techniques, a randomized trial has demonstrated similar efficacy and safety for EMR of early-stage esophageal cancers [34]. EMR-C also uses submucosal injection to lift the target lesion. Dedicated mucosectomy devices that use a plastic cap with rim and a specialized crescent-shaped electrocautery snare have been developed [35]. The snare must be opened and placed on the internal circumference rim at the tip of cap, which is attached on the end of the forward-viewing endoscope. Once the endoscope is positioned over the lesion, suction is applied to retract the lesion into the cap, and the snare is closed to capture the base of the pseudopolyp. The lesion is then resected with a standard snare excision (Fig. 11.3c). Different sized and shaped caps are available based on the tumor size and location (Fig. 11.4). The straight caps are commonly used for the lesions in the stomach and colon and the oblique-shaped caps are usually used in the esophagus where a tangential approach is often required [35] .

Fig. 11.4

Different size and shape of the caps utilized for endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR). On the left; straight hard cap. In the middle, oblique-shaped soft cap. On the right; oblique-shaped hard cap. (Permission for use granted by Olympus Medical Systems Corp., Japan)

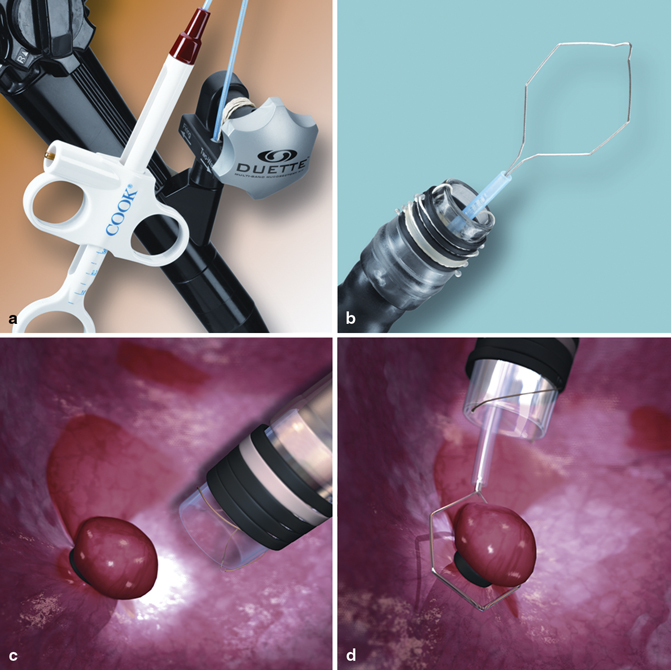

EMR-L uses a cap attachment with band ligation device (Fig. 11.3d). The device is positioned over the target lesion with or without prior submucosal injection. Suction is applied to retract the lesion into the cap and the band is deployed underneath it creating a pseudopolyp. The pseudopolyp is then resected at its base with an electrocautery snare [36]. The band has enough contractile force to squeeze the mucosal and submucosal layers, but it is not strong enough to capture the muscularis propria. A multiband ligation system was developed to avoid the repeated withdrawal and insertion of the endoscope for band ligation and subsequent resection (EMR-MBL). In our practice, a multiband mucosectomy device (DuetteTM, Cook Medical Inc., Bloomington, IN) is commonly used (Fig. 11.5). This device includes a specially designed six-band ligator, through which a polypectomy snare can be passed, and the band ligation and subsequent resection can be performed in series without withdrawal of the endoscope.

Fig. 11.5

Multiband mucosectomy device. a and b Multiband mucosectomy kit. c Pseudopolyp created by ligation. d Snare wire is applied on its base to resect. (Permission for use granted by Cook Medical Incorporated, Bloomington, Indiana)

The advantages of EMR-C and EMR-L/EMR-MBL techniques would be their simplicity, which only requires the use of a standard endoscope. However, the limitation of EMR is that it cannot be used to remove en bloc lesions larger than 2 cm. Again, piecemeal resection for lesions larger than 2 cm leads to a higher risk of local recurrence and insufficient pathological staging [31, 37]. Thus, a technique to remove larger lesions en bloc was developed [38, 39].

Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection

ESD was developed in Japan for en bloc removal of lesions larger than 2 cm in diameter [38–40]. It is an advanced endoscopic resection technique, which involves direct dissection of the submucosal layer using a specialized needle knife. Since the first introduction of ESD using an insulation-tipped knife in Japan [39], various types of needle knives have been developed and introduced into practice (Fig. 11.6). En bloc resection of lesion allows more accurate pathological evaluation of the lateral and radial margins and reduces the risk of local recurrence [41, 42]. ESD requires several steps, and only carbon dioxide insufflation should be used (Fig. 11.7). First, the margin of the lesion (normal mucosa around the lesion) is marked by electrocautery, which is critical for the success of en bloc resection of large lesions. Then, submucosal injection is used to lift the lesion. In practice, it is preferred to use sodium hyaluronate solution (approximately 0.5 % solution) mixed with epinephrine (0.01 mg/ml) and indigo carmine (0.04 mg/ml), which remains in the submucosal space for a longer period compared with other solutions such as saline and glycerol [43, 44]. Next, the mucosa is incised for a distance of 5 mm outside of the radial margin markings using a needle knife. Once the access to the submucosal space is created, appropriate tension and counter-tension are maintained using cap placed on the insertion tube of the endoscope, which is inserted into submucosal space. The dissection is performed using a needle knife by dissecting submucosal tissues and bridging vessels within the submucosal space. Large vessels should be cauterized using hemostatic forceps. At the completion of the procedure, the lesion should be removed en bloc regardless of its size, preserving a thin layer of submucosa (sm3) overlying the muscularis propria. Hemostasis should be completed by coagulating visible vessels with hemostatic forceps to prevent post-procedure bleeding. To maintain adequate countertraction between the mucosal–submucosal complex and muscularis propria, it is important to consider how to make the initial mucosal incisions. Partial mucosal incisions should be made first at the most proximal and distal aspects of the tumor; a submucosal tunnel is then created, thereby linking these two openings and exploiting the added countertraction offered by the intact mucosa on the sides flanking the tunnel. The flanking mucosa is then cut, thereby freeing the tumor. It is important to work from proximal to distal locations so that the dissected portion of the tumor can be “pulled” out of the way by gravity .

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree