Chapter 53 Endoscopic Drainage of Pancreatic Pseudocysts, Abscesses, and Walled-Off (Organized) Necrosis

Video for this chapter can be found online at www.expertconsult.com.

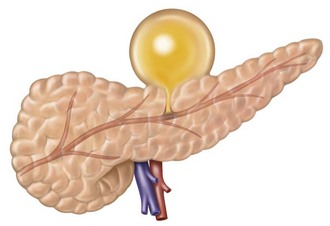

Specific Types of Fluid Collections

Classification systems for defining types of PFCs are useful for understanding mechanisms of formation and allowing comparisons of therapies between and among disciplines. Since the previous edition of this text the classification and nomenclature for PFCs has been revised1 and continues to evolve.

However, the approach can be simplified by addressing three questions: (1) Is the collection a result of pancreatitis or does it represent a cystic neoplasm (see Chapter 48)? (2) Is the collection composed primarily of liquid or does it contain significant solid debris? (3) What is the PD anatomy? Using these three basic questions, the short- and long-term approaches to the patient with a PFC can be formulated. The approach to collections that are composed primarily of fluid is different than the approach to those containing significant solid debris, since liquified collections can be managed with placement of small diameter stents via a transpapillary or transmural approach alone, whereas those with solid debris usually require aggressive transmural dilation to allow egress of solid material and placement of large bore stents and/or irrigation catheters and are associated with worse outcomes.

Collections Composed Entirely or Predominantly of Liquid

1. Acute fluid collections. Acute fluid collections arise early in the course of acute pancreatitis, are usually peripancreatic in location, and usually resolve without sequelae but may evolve into pancreatic pseudocysts.1

3. Pancreatic abscesses. True pancreatic abscesses are rare and not synonymous with infected pancreatic pseudocysts.1 However, for the purposes of this chapter and based on pending revisions of the existing nomenclature, an abscess will be considered as an infected PFC that contains little to no solid debris (as opposed to infected pancreatic necrosis, which is described later). I believe that when this definition is used, abscesses can be drained through modest-sized catheters without absolute need for irrigation or debridement.

Indications for Drainage of Liquified Collections

Symptoms related to sterile pancreatic collections include abdominal pain, often exacerbated by eating, weight loss, gastric outlet obstruction, obstructive jaundice, and PD leaks. PD leaks can manifest as pancreatic ascites or high-amylase pleural effusion and pancreatic fistulae and are discussed in Chapter 51. Infection is considered an absolute indication for drainage.

Predrainage Evaluation

1. Establish whether the collection represents a PFC or a “masquerader” of a PFC such as a cystic neoplasm or other entity (Box 53.1; Fig. 53.3). If the patient does not have a well-documented history of acute or chronic pancreatitis, the endoscopist should be concerned that the collection does not represent a pseudocyst or other inflammatory collection. With the development of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), cystic neoplasms have been better recognized and defined. However, clinical judgment and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) can also be useful in making this differentiation. Cystic neoplasms are discussed in more detail in Chapter 48.

2. Establish whether the collection is predominantly liquid or contains a significant amount of solid debris.

3. Establish the relationship of the collection to surrounding luminal and vascular structures.

4. Consider underlying etiologies of true pancreatic pseudocyst that have implications for alternative or adjuvant therapies, such as pancreatic cancer, autoimmune pancreatitis, and intraductal pancreatic mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs).

1. Coagulation profile in patients with a suspicion of coagulopathy and/or liver disease, especially when transmural drainage is considered.

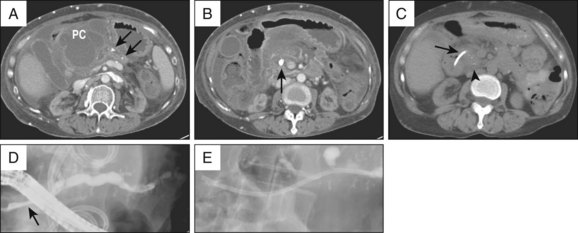

2. Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT). This allows assessment of the precise location of the collection in relation to the stomach and duodenum in anticipation of possible transmural drainage. Additionally, the relationship of the collection to potential intervening vascular structures can be assessed. Surrounding varices from splenic vein or portal vein thrombosis also may be visualized. The finding of inhomogeneity within the collection suggests the presence of underlying solid debris and/or blood (Fig. 53.4).

Consideration should be given to the following additional studies:

1. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS). EUS can be used prior to drainage to allow assessment for the presence of significant solid debris that may alter the management strategy. In addition, if there is uncertainty as to whether the collection represents a true pseudocyst or other noninflammatory cystic lesion, EUS allows one to obtain a definitive diagnosis by using ultrasonographic features, aspiration and analysis of cyst contents, and biopsy of the cyst wall. Once the endoscopist is certain that the lesion in question is a PFC and the decision has been made to proceed with endoscopic drainage, EUS may be used to guide transmural drainage as discussed in the next section.

2. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with or without MRCP. MRI also allows detection of the presence of solid debris, so that plans for removal and/or alternative drainage strategies can be chosen depending on local expertise and necrosis drainage preferences. MRCP can define the ductal anatomy and be augmented by secretin stimulation. Secretin-enhanced MRCP (S-MRCP) may demonstrate the presence or absence of an ongoing ductal disruption.

Drainage Techniques

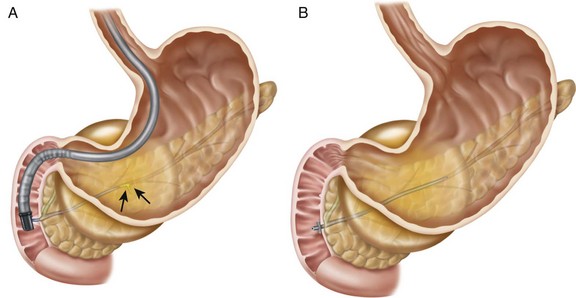

Liquified PFCs may be drained using a transpapillary approach, transmural approach, or a combination of these.2,3 The decision to use one approach over the other depends on the size of the collection, its proximity to the stomach or duodenum, and the ability to enter the pancreatic duct and/or reach the area of disruption.4 For example, although the intended approach to draining a pseudocyst that formed from an obstructing PD stone may be transpapillary (Fig. 53.5, A and B), failure to negotiate a guidewire beyond the obstructing ductal stone may require transmural drainage. Assessment and treatment of the ductal stone at a later date by other techniques such as extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) can then be performed (Fig. 53.5, C to E).

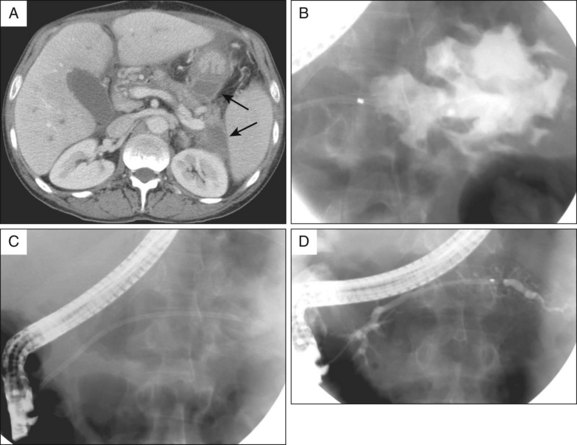

Transpapillary Drainage

If the collection communicates with the main pancreatic duct, placement of a pancreatic endoprosthesis with or without pancreatic sphincterotomy is an approach that is useful, especially for collections measuring ≤6 cm that are not otherwise approachable transmurally.5,6 The upstream end of the stent (toward the pancreatic tail) may enter the collection directly or bridge the area of leak into the pancreatic duct upstream from the leak (Fig. 53.6). The latter is the preferred approach (Fig. 53.7) since it restores ductal continuity. In patients with chronic pseudocysts it is important that the stent bridge any obstructive process (stricture or stone) between the duodenum and the leak site. The diameter of pancreatic stent used is dependent on the pancreatic ductal diameter (see Chapters 21 and 52), although 7 Fr stents are most frequently used. In patients with chronic pancreatitis, endoscopic therapy of underlying PD strictures and pancreatic stones may reduce the recurrence rate of pancreatic pseudocysts.7

The advantage of a transpapillary approach compared to a transmural approach is avoidance of bleeding and perforation. The disadvantage of transpapillary drainage is the potential for pancreatic stent-induced ductal injury in patients whose PD is otherwise normal. Examples include patients with acute pseudocysts and small side branch disruption and patients with ductal tail leaks after distal (tail) pancreatectomy (see Chapter 42).

Transmural Drainage

Transmural Entry Devices

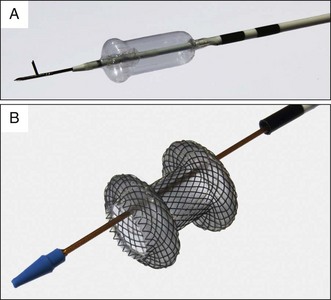

Devices used to perform transmural puncture of a collection can be divided into cautery and noncautery devices. Cautery devices include standard diathermy wires (needle knives) and specialized fistulotomy devices (Cystotome, CST-10, Cook Endoscopy, Winston-Salem, N.C.). Noncautery devices include EUS fine-needle aspiration (FNA) needles and other miscellaneous aspiration needles (Marco-Haber variceal injector needle MHI-21, Cook Medical), although only one dedicated noncautery pseudocyst needle is currently available (NAVIX Access Device, Xlumena, Mountain View, Calif.; Fig. 53.8).

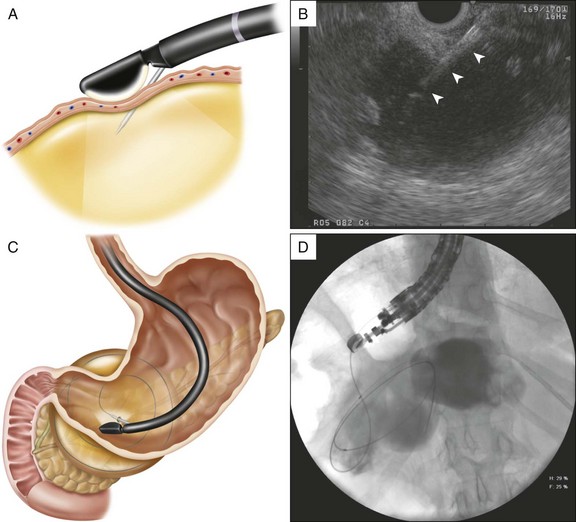

EUS-Guided Transmural Drainage

EUS imaging may reduce adverse events related to transmural entry of PFCs, although this has not been proven.8 EUS localization of the collection can be followed by a second non-EUS-guided endoscopic puncture,9 although this can be inaccurate. EUS-guided puncture is similar to EUS-guided FNA (Fig. 53.9; see Chapter 30). Using a linear echoendoscope with or without Doppler capabilities, successful entry and one-step drainage has been reported in approximately 94% of patients with low adverse event rates, including those without an endoscopically visible extrinsic compression.9,10 Lack of EUS availability, however, does not preclude transmural drainage except in the following instances: small “window” of entry based on CT, especially in the absence of an endoscopically defined area of extrinsic compression or unusual location; coagulopathy or thrombocytopenia; documented intervening varices9; and failed transmural entry using non-EUS-guided techniques. Indeed, a randomized trial of EUS and non-EUS drainage found non-EUS-guided drainage to be an acceptable first-line therapy in patients with bulging collections.11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree