Endometriosis and the Uterus

Shawky Z.A. Badawy

Steve Landas

Endometriosis is a chronic disease process that affects women during their reproductive years. It is estimated that about five million women in the United States suffer from this problem. Several studies have demonstrated the presence of endometriosis in teenage women who suffer from chronic pelvic pain. About 50% of women with infertility have some degree of endometriosis.

Endometriosis remains an enigma with regard to its cause, clinical presentation features, and natural history. Sampson described the reflux theory in which menstrual fluid flows from the uterus through the fallopian tubes into the peritoneal cavity. This view holds that menstrual fluid contains viable endometrial cells that survive, attach to the coelomic epithelium, and produce endometriosis. This menstrual fluid may irritate the coelomic epithelium and lead to metaplasia and formation of endosalpingiosis or endometriosis. This theory offers a plausible explanation of endometriosis that occurs in the pelvis and, perhaps, part of the abdominal cavity.

Endometrial tissue from the uterus may gain access to the venous and lymphatic system of the uterus, leading to embolization to distant locations. This line of thought may explain endometriosis of the lungs, pleura, diaphragm, and liver, and scars of cesarean sections and episiotomies. These data suggest that the normal uterine function is an important factor in the development of endometriosis. Endometriosis has not been reported in women with absence of müllerian system development. Peritoneal pouches in close proximity to the uterosacral ligaments occasionally contain foci of endometriosis, offering support to the theory of müllerian remnants in the development of endometriosis.

Pathogenesis

Endometriosis is described as endometriumlike tissue present in any location outside the uterine cavity. Histologically, this tissue contains both glands and stroma indistinguishable in many respects from normal endometrium. Biopsies, however, may show the presence of stroma, glands, or both in various lesions. These lesions are typically surrounded with a fibrotic rim and contain hemosiderin-laden macrophages. This produces the clinical picture of “gunpowder”-type lesions as identified laparoscopically. Menstrual cycling of endometriosis may not coincide with the cycle of the normal endometrium. This may be related to the relative lack of estrogen and progesterone receptors in the endometriotic tissue (compared with normal endometrium). This raises the issue of the role of hormones and other factors contributing to the continued growth and proliferation of endometriosis. Although estrogen and progesterone are essential for the development of the disease process of endometriosis, other factors play a key role in maintaining this tissue. These include transforming growth factor β, vascular endothelial growth factor, tumor necrosis factor, and other antiapoptotic factors.

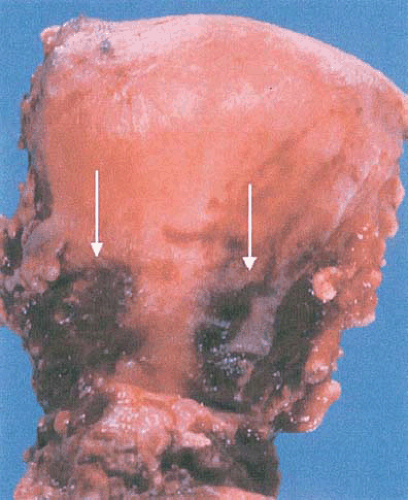

Morphologically, endometriosis has been described in various forms including the typical pink spots with or without gunpowder lesions (Fig. 5.1), vesicular lesions, white scars, and deep infiltrating lesions with nodularity, especially in the uterosacral ligaments. All of these patterns occur in the peritoneum of the pelvic cavity including the surface of the urinary bladder, uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and uterosacral ligaments as well as elsewhere in the abdominal cavity, especially the intestines and the diaphragm.

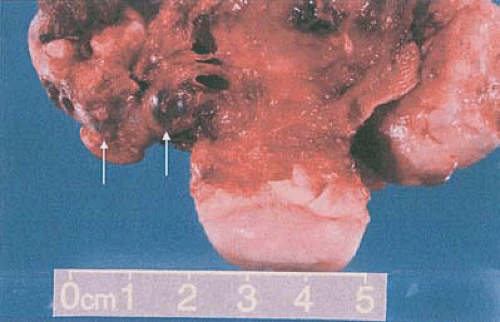

Endometriosis may infiltrate organs like the ovaries and intestines and grow inside, developing cystic lesions called endometriomas (Fig. 5.2) or chocolate cysts. These lesions may reach a very large size. The chocolate-colored material represents the degenerating accumulated bloody discharge from the functioning endometriotic tissue.

Endometriosis of the lungs and pleura have been described in women with cyclic hemoptysis. This may represent metastatic embolic lesions from the endometrium into the pulmonary system. Endometriosis has also been described in cesarean section scars and episiotomy scars, leading to cyclic pain.

Many studies have demonstrated the marked inflammation that occurs in the pelvic cavity with endometriosis. There is increased cul-de-sac fluid containing high numbers of macrophages and T and B lymphocytes. Prostaglandins F2α and E2 as well as various interleukins are also present in such fluid. Activation of the immune system leads to the formation of antibodies, antigen–antibody complexes, and subsequent inflammatory changes and adhesions. The end result of the inflammatory and scarring process makes dissection

and removal of lesions difficult. There may be extensive distortion simulating neoplasm (this disease process has been classified by the World Health Organization [WHO] as a tumorlike lesion).

and removal of lesions difficult. There may be extensive distortion simulating neoplasm (this disease process has been classified by the World Health Organization [WHO] as a tumorlike lesion).

FIGURE 5.1 This hysterectomy specimen shows dark red to gray serosal discoloration (white arrows) characteristic of the gunpowder burn appearance of “burned out” endometriosis. |

Adenomyosis of the Uterus

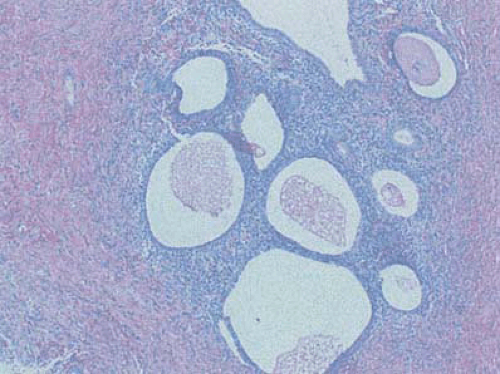

This category of endometriosis is characterized by endometrium present deep in the myometrium, sometimes called endometriosis interna. This is in contrast to endometriosis in the pelvic cavity or other locations, termed endometriosis externa. Adenomyosis may occur at any age, usually presenting at age 30 to 50 years as severe dysmenorrhea or irregular uterine bleeding. The lesions are composed of endometrial glands and stroma surrounded by the muscle of the uterus (Fig. 5.3). These foci sometimes connect to the basal endometrium. Hypertrophy of the musculature of the uterus will lead to uterine enlargement simulating a fibroid uterus on pelvic examination. Adenomyosis leads to localized expansion of the myometrium and masses in the uterine wall that mimic myomas (Fig. 5.4). Surgically, myomas have a plane of cleavage between the myoma and normal uterine wall that allows enucleation. However, adenomyosis offers no plane of cleavage and cannot be easily removed surgically. In response to ovarian hormones, these lesions undergo cyclic bleeding and shedding, causing uterine tenderness. Some patients experience severe pain. The incidence of adenomyosis in surgical specimens has been estimated to be between 10% and 47%. Frequently, myomas and adenomyosis occur in the same patient (46% to 50%). Adenomyosis was found to be prevalent in uteri with previous surgical interventions.

FIGURE 5.2 This anterior view of a hysterectomy specimen and bilateral adnexa shows multiple dark red, blood-filled cysts: Endometriomas (arrows). |

Clinical diagnosis of adenomyosis is difficult as the clinical signs, symptoms, and physical findings may be subtle, vague, or nonspecific. The uterus may be enlarged and tender during pelvic bimanual examination in a woman during her third or fourth decade of life. Recently, however, ultrasonography and MRI have proven helpful in making the diagnosis in some patients. Ultrasonography reveals an enlarged uterus which contains echogenic cysts in an otherwise homogenous uterine wall. MRI, with greater resolution, offers even greater diagnostic benefit, often showing an enlarged junctional zone in addition to myometrial cysts.

FIGURE 5.3 Adenomyosis, foci of endometrial glands and stroma deep within the myometrium, distort the uterine wall. (10×, hematoxylin and eosin.) |

Adenomyosis is found commonly in the fundus of the uterus and rarely in the cervix, confirmed by histopathologic review. Supracervical hysterectomy, therefore, is effective treatment in such patients. Rare cases of infection in adenomyosis uteri and abscess formation have been reported. Also, adenocarcinoma arising in foci of adenomyosis have been described in several cases. Intramural pregnancy was reported in a uterus with adenomyosis; however, the cause and effect is not known. The mutations in estrogen receptors and the demonstration of estrogen sulfatase may be a factor in the etiology of adenomyosis uteri in such patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree