Adenocarcinoma of the Endometrium

Jack Basil

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States. An estimated 41,200 new cases of endometrial cancer will be diagnosed in 2006, and 7,350 deaths will be attributed to endometrial cancer during the year (Jemal et al.). Women have about a 2.6% lifetime risk of developing endometrial carcinoma, and 65 years is the median age of diagnosis. In general, most patients diagnosed with endometrial carcinoma present with abnormal bleeding, and most cases are found early in the disease process. Surgery is the cornerstone of therapy for this malignancy. Radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy are reserved for poor surgical candidates, postoperative patients with poor prognostic factors, advanced-stage disease, or for those patients with recurrent disease. The overall prognosis for patients with endometrial carcinoma is closely related to stage of disease and in general is quite favorable.

Risk Factors

Many of the risk factors for endometrial carcinoma are related to excess estrogen exposure. Until the early 1970s, estrogen alone was commonly given to combat the vasomotor symptoms of menopause. Smith et al. demonstrated a four and one-half times increased risk of endometrial carcinoma in those taking unopposed estrogen. It is now commonplace to add progestins to estrogen in women with an intact uterus who desire hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for vasomotor symptoms of menopause. Early menarche, late menopause, nulliparity, and chronic anovulation all increase the lifetime exposure to estrogen and in turn elevate the risk of endometrial adenocarcinoma. Obesity increases the risk of endometrial cancer by the peripheral conversion of estrone to estradiol in the adipose tissue. Granulosa cell tumors of the ovary can secrete estrogen and increase the risk of endometrial carcinoma and endometrial hyperplasia.

Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen receptor modulator used to treat some women with breast cancer or women at an increased risk of developing breast cancer. This medication has a weak stimulatory effect on the uterine lining and has been shown to increase the risk of endometrial carcinoma. Any woman with abnormal bleeding while taking tamoxifen should have an endometrial sampling procedure to rule out malignancy.

Age increases one’s risk of endometrial carcinoma. The average age of diagnosis is approximately 63 years of age. Up to 90% or more of endometrial carcinomas present in women older than 40 years of age. Some other factors more loosely associated with endometrial carcinoma include diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and a high dietary fat intake.

About 5% to 10% of all endometrial cancers are hereditary. Most of these occur in families affected by hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (HNPCC), also known as Lynch II syndrome. HNPCC is an autosomal dominant family cancer syndrome characterized by mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes. Endometrial carcinoma is the second most common malignancy found in these families.

Combination oral contraceptive pills (OCP) have shown to protect against endometrial carcinoma. Hulka et al. have shown that the risk of endometrial carcinoma in OCP users was less than half that of nonusers. Smoking decreases the risk of developing endometrial cancer. The exact mechanism for this is unknown, but is thought to involve absorption and metabolism of hormones. This decreased risk of endometrial carcinoma in smokers is far outweighed by the many adverse effects of smoking.

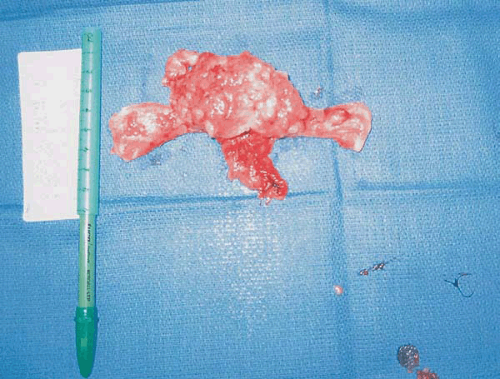

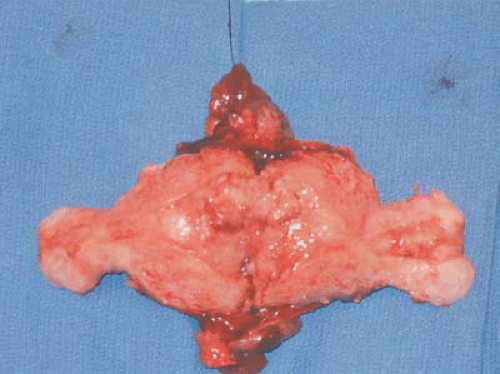

Several authors have proposed two distinct types of endometrial carcinoma. The most common (type I) is the endometrioid subtype, which has been shown to be an estrogen-associated lesion often seen in conjunction with endometrial hyperplasia. Figure 7.1 shows an endometrial adenocarcinoma endometrioid subtype. Type I endometrial carcinoma is associated with excess estrogen, either endogenous or exogenous. Generally, type I endometrial carcinomas are earlier stage, with less myometrial invasion, better tumor differentiation, and a more favorable prognosis when compared with type II endometrial carcinomas. Type II endometrial carcinoma tends to affect older patients and be of a more virulent histologic subtype, such as papillary serous or clear cell. Patients with these more aggressive histologies less commonly have a history suggestive of excess

estrogen exposure. Figure 7.2 shows a papillary serous endometrial adenocarcinoma.

estrogen exposure. Figure 7.2 shows a papillary serous endometrial adenocarcinoma.

FIGURE 7.1 A bivalve hysterectomy specimen revealing endometrioid adenocarcinoma involving the uterine fundus. |

TABLE 7.1 Modified Amsterdam Criteria for the Diagnosis of Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colon Cancer (HNPCC) | |

|---|---|

|

Signs and Symptoms

Most endometrial carcinomas are detected early because the majority of patients present with abnormal vaginal bleeding. Up to 90% of patients diagnosed with endometrial carcinoma will have this precursor bleeding. Other signs and symptoms of endometrial carcinoma may include vaginal discharge, abdominal or pelvic pain, changes in bowel or bladder function, and shortness of breath. Most of these would suggest more advanced disease. Figure 7.3 shows multiple pulmonary nodules representing metastatic disease in a patient with endometrial carcinoma who presented with irregular vaginal bleeding and progressive shortness of breath.

There is no universally recommended screening test for endometrial carcinoma for the general population. The following groups are at an increased risk of endometrial carcinoma, and screening is recommended. Women who meet criteria for HNPCC have a 40% to 60% lifetime risk of endometrial cancer. These women should be screened with an annual endometrial biopsy after 35 years of age. Table 7.1 outlines the modified Amsterdam criteria for the diagnosis of HNPCC. These patients should also be counseled regarding prophylactic surgery. Those women who experience vaginal bleeding while taking tamoxifen should undergo endometrial biopsy. Also, women with chronic anovulation should be considered for endometrial biopsy.

Diagnosis

The gold standard for the diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma is an endometrial biopsy. A general rule of thumb is to perform an endometrial biopsy or sampling on patients over

35 years of age who experience irregular vaginal bleeding and in all postmenopausal patients who have vaginal bleeding except those on cyclical hormonal therapy. Endometrial biopsy can often be performed in the office setting. Endometrial Pipelle biopsy has been shown to have sensitivity for detecting endometrial carcinoma of >95%. In cases where office biopsy cannot be performed secondary to cervical stenosis or patient discomfort, a D&C procedure is recommended. A D&C procedure should also be considered if the office biopsy is insufficient for diagnosis or shows atypical cells not diagnostic for carcinoma.

35 years of age who experience irregular vaginal bleeding and in all postmenopausal patients who have vaginal bleeding except those on cyclical hormonal therapy. Endometrial biopsy can often be performed in the office setting. Endometrial Pipelle biopsy has been shown to have sensitivity for detecting endometrial carcinoma of >95%. In cases where office biopsy cannot be performed secondary to cervical stenosis or patient discomfort, a D&C procedure is recommended. A D&C procedure should also be considered if the office biopsy is insufficient for diagnosis or shows atypical cells not diagnostic for carcinoma.

FIGURE 7.3 A chest radiograph revealing numerous pulmonary nodules that represent metastatic endometrial cancer. |

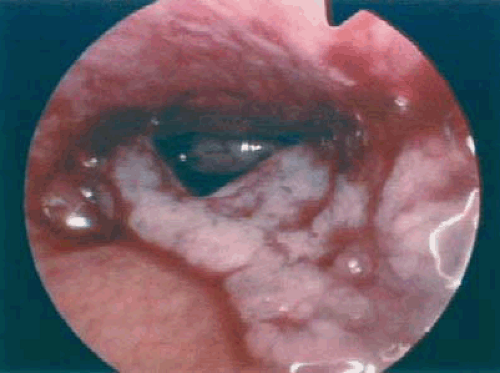

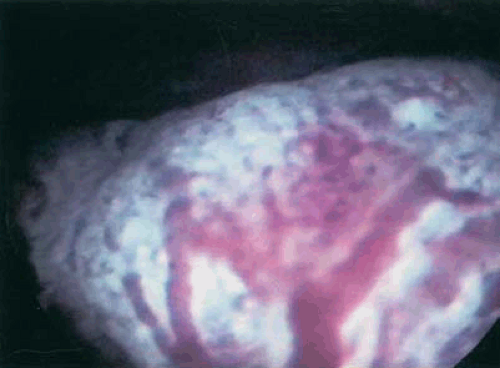

The role, if any, for hysteroscopy in the evaluation of women suspected of having endometrial carcinoma is unclear. Several authors have demonstrated an increased risk of dissemination of endometrial cancer cells into the peritoneal cavity with the use of hysteroscopy. Whether positive peritoneal cytology alone as an isolated prognostic factor adversely affects overall prognosis is controversial. Ben-Yehuda et al. demonstrated that hysteroscopy did not improve the sensitivity of D&C in the detection of endometrial carcinoma. This author does not routinely use hysteroscopy in the evaluation of women suspected to have endometrial carcinoma. Figures 7.4 to 7.6 show hysteroscopic views of endometrial adenocarcinomas.

Staging

Both the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) recommend the use of surgical staging for endometrial carcinoma (Table 7.2). FIGO adopted its current surgical staging criteria in 1988 because several important prognostic factors could not be obtained through the clinical staging system. Surgical staging for endometrial carcinoma has been shown to be more predictive of prognosis compared with the clinical staging system.

The definition of appropriate surgical staging for patients with endometrial adenocarcinoma remains undefined. Full surgical staging including total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy, and pelvic washings has been shown to benefit most women with endometrial carcinoma. Kilgore et al. were the first to demonstrate a therapeutic benefit in patients who underwent removal of lymph nodes during surgical staging. More recent studies confirm the survival advantage and also show that performing pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy greatly helps to facilitate postoperative therapy. This lessens the number of women who are both undertreated and overtreated in the postoperative period. A recent study by Ben-Shacher et al. revealed that complete surgical staging in patients with grade 1 endometrial carcinomas significantly affected treatment decisions in almost one third of cases. These authors concluded that omitting lymphadenectomy in patients with grade 1 endometrial carcinomas might lead to inappropriate postoperative management.

Approximately 22% of grade 1 tumors invade into the middle or outer third of the myometrium. An upgrading of tumor differentiation of 15% to 20% in grade 1 tumors has been demonstrated when preoperative biopsy or D&C is compared with the final histologic specimen. Simple intraoperative palpation of the lymph nodes has been shown to be inaccurate and should not be used as a substitute for histopathologic evaluation. Because of these factors, it seems justified to plan a full staging procedure to include pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy for all patients undergoing surgical management of endometrial carcinoma. The exception to this may be in those endometrial cancer patients with significant comorbidities.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree