Chapter 56 Emerging Intramural and Transmural Endoscopy

![]() Video related to this chapter’s topics: Endocytoscope observation of the muscularis propria in the stomach with SEMF technique

Video related to this chapter’s topics: Endocytoscope observation of the muscularis propria in the stomach with SEMF technique

Introduction

Limitless possibilities exist for the endoscope to serve as a sophisticated diagnostic probe and a platform for endoluminal therapeutic interventions. Flexible gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy has achieved major accomplishments so far, which include inspection of the total digestive canal, detection of grossly invisible minute mucosal abnormalities, reliable hemostasis for GI bleeding, pancreaticobiliary intervention, ultrasound staging of neoplasms, and radical excision of mucosal malignancies. Despite these practical technologic accomplishments, the working space for flexible endoscopy has been confined to the gut lumen. The gut wall has always been the great barrier for flexible endoscopy, instilling a tradition of respect to maintain its integrity and limiting intervention. Both gastroenterologists and surgeons are now exploring the new frontier through the gut wall to achieve incisionless surgery.1 More recent research has approached the gut wall as an opportunity and showed that an artificially created intramural space could become a working space for novel endoscopic interventions.2,3

Techniques for Creation of a Submucosal Working Space: Submucosal Endoscopy with Mucosal Safety Valve Technique

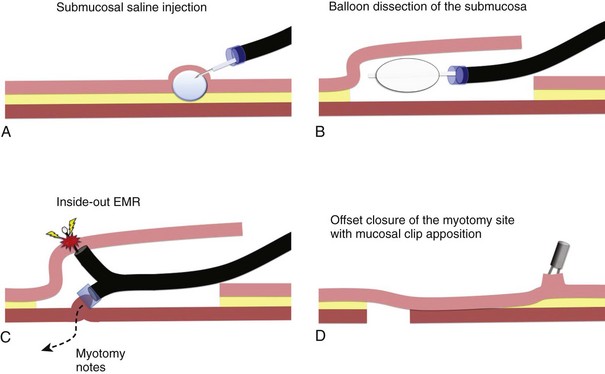

The submucosal endoscopy with mucosal flap (SEMF) “safety valve” technique represents a global concept of using a submucosal space as a practical working space for endoscopic intervention.4 Using the SEMF technique, major technical challenges to standard endoscopic intervention may be overcome by using the endoscope and surgical devices inserted into the intramural space—formally the submucosa. It was hypothesized that the technique may offer safe (offset) access into the peritoneal cavity for natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) by using the submucosal space as a tunneled portal and the isolated free overlying mucosa as a protective sealant flap to minimize the potential for contamination of the extraluminal anatomic cavity (Fig. 56.1).3 Also, mucosal resection could be safely performed in an “inside-out” manner, directing intervention toward the lumen with a greatly reduced risk of perforation, regardless of the size for a mucosal based lesion.5

In the original SEMF technique,6 the submucosal layer was mechanically dissected by a combination of high-pressure carbon dioxide (CO2) and balloon dissection. The procedure was initiated by a submucosal injection of a small amount of saline to identify the submucosal tissue plane (see Fig. 56.1A). Millisecond bursts of high-pressure CO2 (100 psi on average) were injected into the bleb to create a gas-filled giant submucosal bleb and gas-dissected submucosa. This gas dissection technique allows instant isolation of a large area of the mucosa as desired, greater than 10 cm in diameter. An injection of 1.5% hydroxypropyl methylcellulose into this dissected plane prevents gas escape and maintains the large bleb. A mucosal incision (10 mm) made with a needle-knife at one margin of the combination bleb and fluid cushion allows entry below the mucosa. With persistent submucosal tissue stranding present, balloon dissection using a 15-mm biliary retrieval balloon can be performed to disrupt the tissue strands to transform the submucosa into an intramural free space (see Fig. 56.1B). Instead of the combination of gas and balloon dissections, blunt dissection with a grasping forceps also could be used for the mechanical disruption of the submucosal layer. In contrast to the SEMF technique and long preceding it, Japanese endoscopists have used repetitive time-consuming needle-knife dissection directed into the submucosal plane using one of a series of needle-knives specially designed for endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) technique.

Chemically Assisted Submucosal Dissection Technique

The original gas dissection SEMF technique was developed with the intent of rapidly creating an open submucosal space. This technique can be slow because of tedious balloon dissection in the setting of a resilient submucosa. The large mucosal flap can be susceptible to necrosis because of inadvertent mechanical trauma and, perhaps, microvascular ischemia. To preserve blood supply of the free mucosal flap, it is necessary to identify an optimal width and length of the submucosal tunnel or space matched to the specific intervention. In an effort to minimize mechanical trauma to the mucosal flap, we have discovered mesna (C2H5NaO3S2) as a practical pretreatment of the submucosa before the blunt dissection. Mesna can chemically soften the submucosa by dissolving disulfide bonds in connective tissues that play an important role in the folding and stability of proteins.7 Mesna is clinically used as a mucolytic agent for patients with respiratory disorders and is better known in oncology as a uroprotective drug to prevent ifosfamide-induced and cyclophosphamide-induced hemorrhagic cystitis. Drug safety has been shown from these clinical experiences.

The concept of chemically assisted surgical dissection with mesna was initially introduced to assist blunt dissection of the facial planes in the field of otorhinolaryngology. The benefits of mesna have been confirmed in other surgical interventions. In the chemically assisted SEMF technique, 4 to 8 mL of 10% mesna solution is injected into the saline submucosal bleb before initiating balloon dissection. A randomized porcine study using this method showed that a longitudinal submucosal tunnel greater than 5 cm could be created within 10 minutes in porcine stomachs with significantly less tissue resistance to insertion of a balloon catheter and subsequent mechanical balloon dissection. Clinical experience has subsequently been obtained using mesna to facilitate excision of colon polyps and gastric neoplasms.8 The preliminary clinical experiences in the stomach and colon support the benefits of mesna in “softening” the submucosa.