Chapter 56 DYNAMIC MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF PELVIC ORGAN PROLAPSE

Weakness and subsequent dysfunction of the pelvic floor is common in parous women of middle or advanced age. Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and pelvic floor relaxation are caused by anatomic abnormalities, including weakness of the muscles of the pelvic floor and the fascial attachments of the pelvic viscera. The prevalence of POP has been reported to be as high as 16% of women aged 40 to 56 years.1 Approximately 500,000 surgeries for POP are performed in the United States each year.2

Women with POP present not only to the gynecologist but also to the urologist, as up to one third of patients with prolapse also suffer from urinary incontinence. POP is also associated with fecal incontinence, incomplete voiding, and constipation. A detailed knowledge of pelvic anatomy is paramount for the proper evaluation and management of such conditions. Pelvic support defects result from both neurophysiologic and anatomic changes3 and often occur as a constellation of abnormal findings. Symptomatic individuals often have multifocal pelvic floor defects, not always evident on physical examination.4

Even experienced clinicians may be misled by the physical findings, having difficulty differentiating among cystocele, enterocele, and high rectocele by physical examination alone. Depending on the position of the patient, the strength of the Valsalva maneuver, and modesty of the patient, the examiner may be limited in his or her ability to accurately diagnose the various components of pelvic prolapse. Furthermore, with uterine prolapse, the cervix and uterus may fill the entire introitus, making the diagnosis of concomitant anterior or posterior compartmental prolapse even more difficult. Regardless of the etiology of the support defect, the surgeon must identify all aspects of vaginal prolapse and pelvic floor relaxation for proper surgical planning. Incorrect diagnosis of these defects may lead to inadequate surgical treatment.5 Accurate preoperative staging should reduce the risk of recurrent prolapse, which can occur in up to 34% of patients after surgery.6

RADIOGRAPHIC EVALUATION

Levator Myography

Levator myography is an outdated method of visualizing the pubococcygeus and iliococcygeus via direct injection of contrast solution into the levator muscles. Originally described in 1953, this technique allows visualization of the position and supportive role of these muscle groups.7 Widening of the levator hiatus, which often occurs after traumatic childbirth and predisposes to pelvic floor relaxation and to visceral prolapse, can be demonstrated with levator myography. Today, this information may be obtained noninvasively with CT8 and MRI.9,10

Voiding Cystourethrography

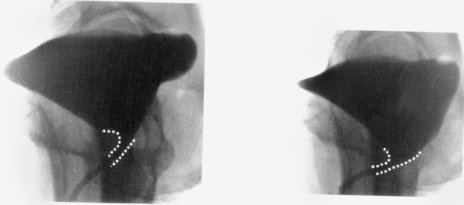

Voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) is mainly used for demonstrating a cystocele, evaluating bladder neck hypermobility, and demonstrating an open bladder neck at rest (sphincteric incompetence). Dynamic lateral cystography at rest and during straining is an important adjunct to the urodynamic evaluation; it is useful for demonstrating the presence of and degree of urethra-vesical hypermobility and cystocele formation (Fig. 56-1).11 In additional, dynamic fluoroscopy has been shown to be more accurate than physical examination in demonstrating an enterocele.12,13 Other pathologic conditions detected by VCUG include vesicoureteral reflux, vesicovaginal fistula, and urethral diverticular disease.

Dynamic Proctography

Dynamic proctography, in the cooperative patient, allows precise identification and quantification of a rectocele, measured as the maximum extent of an anterior rectal bulge beyond the expected line of the rectum.14,15 Limitations of this examination include the cumbersome and potentially painful instillation of rectal barium paste and lack of correlation between the viscosity of the paste and the individual patient’s stool. Modesty makes this a difficult technique for many patients, because they are unable to defecate on command.

Colpocystourethrography

The colpocystourethrogram was first described in France in 1965 and combines opacification of the bladder, urethra, and vagina.16 Modified and made popular in the mid 1970s, the colpocystourethrogram is a dynamic study of pelvic support and function.17 The anatomic relationships among the bladder, urethra, and vagina may be demonstrated, and, when the study is combined with proctography, it may be even more useful in outlining the anatomy of the normal pelvis and of complex POP.

An enterocele, defined as a herniation of the peritoneum and its contents at the level of the vaginal apex, may be appreciated via straining or defecation during colpocystoproctography. This is demonstrated by a widening of the rectovaginal space.18 The accuracy of dynamic colpocystoproctography is even further enhanced by opacification of the small bowel. The patient drinks oral barium 2 hours before the examination. With the vagina, bladder, small intestine, and rectum opacified, the vaginal axis may be measured at rest and with straining, and prolapse of the anterior, middle, and/or posterior vaginal compartment should become evident.

Sonography

Sonography offers a convenient, painless, and radiation-free technique. As with fluoroscopy, a dynamic component may be added to sonography. In particular, dynamic ultrasound allows identification of an enterocele during straining maneuver, evidenced by widening of the rectovaginal septum, diminution of the peritoneal-anal distance, and herniation of bowel contents into the cul-de-sac.19 Ultrasongraphy using an abdominal, rectal, vaginal, or perineal transducer is also useful for demonstrating vesicourethral anatomy,20–23 So-called contrast sonography uses echogenic material instilled into the bladder or vagina and is able to identify bladder neck funneling with straining24 as well as paravaginal defects.25

Computed Tomography

CT pelvimetry is an accurate and reproducible method for measuring pelvic dimensions and the capacity of the maternal birth canal.26,27 However, CT has not been shown to be particularly useful in the evaluation of pelvic visceral prolapse. The components of the levator plate and urogenital diaphragm are better seen in the coronal plane or sagittal view, but CT images are routinely presented in the axial plane. Although CT images can be reconstructed into a coronal view with the use of cumbersome and expensive computer software, poor image quality and distorted spatial resolution has limited the utility of this presentation technique.8

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Most recently, MRI has emerged as an important diagnostic tool, both for evaluating the functional relationships among the pelvic floor viscera and supporting structures and for assessing pelvic pathology. MRI offers the advantages of being noninvasiveness, lack of exposure of the patient and examiner to ionizing radiation, and superior soft tissue contrast and multiplanar imaging without superimposition of structures. Axial images provide information about the urogenital hiatus and its contents, whereas sagittal images more easily demonstrate visceral prolapse. Because static images alone do not demonstrate relevant pelvic floor changes with activity, dynamic MRI has been used to reveal the structural functional changes that occur during stress maneuvers. Those established criteria for abnormality derived from fluoroscopy (colpocystoproctography) are directly applicable to MRI.28

MRI also allows evaluation of all three pelvic compartments simultaneously for organ descent. Kelvin’s group used “triphasic” dynamic MRI, consisting of a cystographic, a proctographic, and a post-toilet phase to facilitate the recognition of prolapsed organs that may be obscured by other organs that remain unemptied.29 Fielding showed that MRI is useful for measuring levator muscle thickness,30 demonstrating focal levator ani eventrations (outpouching) not visible with levator myography,31 and measuring urethral length and the thickness and integrity of periurethral muscle ring.9 Hoyte and colleagues48 demonstrated that the anterior portion of the levator (puborectalis) is typically thinner in women with POP and/or stress incontinence compared with asymptomatic controls—possibly due to muscle atrophy caused by denervation from childbirth injuries or muscle wasting secondary to loss of insertion points for the puborectalis.

Yang and associates were the first to popularize dynamic fast MRI for the evaluation of POP,9 using T1-weighted gradient recalled acquisition in a steady-state pulse (GRASS) sequence, with acquisition times between 6 and 12 seconds. Since then, other investigators have shown that MRI is more sensitive than physical examination for defining pelvic prolapse.5,10,32

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree