Drainage of Pancreatic Pseudocyst

Kfir Ben-David

Kevin E. Behrns

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONSPancreatic pseudocysts arise in the settings of acute and/or chronic pancreatitis and have protean manifestations that may depend on size, location, and underlying pancreatic pathophysiology. Appropriate treatment is dependent on understanding the pathophysiology that led to the formation of the pseudocyst. Pseudocysts that are the result of a bout of acute pancreatitis may require significantly different treatment than those that are a complication of chronic pancreatitis.

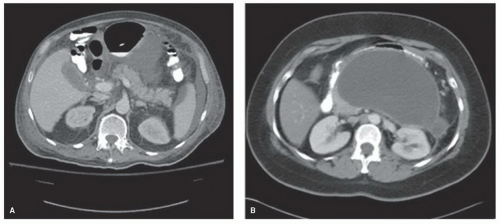

Pseudocysts complicate 27% of acute pancreatitis episodes that may be either acute interstitial (edematous) pancreatitis or acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Establishing the type of acute pancreatitis is critical for appropriate management since a pseudocyst that results from acute interstitial pancreatitis, in which the underlying pancreatic duct is essentially normal with the exception of a single site of disruption, is markedly different from a pseudocyst that forms following acute necrotizing pancreatitis that exhibits substantial destruction of the pancreatic parenchyma and surrounding peripancreatic tissue. In addition, pseudocyst formation occurs over time with a maturation process of approximately 6 weeks. A bout of acute pancreatitis that results in ductal disruption produces a localized collection of pancreatic secretions that incite an inflammatory response which is accompanied by deposition of fibrous tissue that serves to localize and wall-off the injurious fluid. Therefore, over this 6 week time period the pseudocyst takes on a relatively spherical shape with a homogenous internal fluid-filled center as the pancreatic and peripancreatic debris is digested. It is imperative that the clinician recognize this maturation process and not quickly treat an ill-defined pancreatic or peripancreatic fluid collection (acute fluid collection) that results from the inflammatory response but is not associated with pancreatic ductal disruption (Fig. 12.1). These acute fluid collections will spontaneously resolve over time and, therefore, treatment of a presumed pseudocyst should generally not occur until the pathophysiologic process has been clearly established.

Chronic pancreatitis is more frequently associated with pseudocyst development than acute pancreatitis. Up to 40% of patients with chronic inflammation will manifest pseudocyst development at some time in the course of disease; however, many of these pseudocysts are small, asymptomatic and, thus, do not require treatment. Chronic

pancreatitis is characterized by fibrosis and acinar cell drop out that over time results in ductal strictures, parenchymal atrophy, and decreased exocrine and endocrine functions. As a result of the fibrotic process, pancreatic strictures and ductal hypertension produce duct disruption with pseudocyst development. Since a permanently stenotic or an occluded pancreatic duct will frequently not improve over time, pseudocysts that arise in this setting and are symptomatic will frequently require treatment.

pancreatitis is characterized by fibrosis and acinar cell drop out that over time results in ductal strictures, parenchymal atrophy, and decreased exocrine and endocrine functions. As a result of the fibrotic process, pancreatic strictures and ductal hypertension produce duct disruption with pseudocyst development. Since a permanently stenotic or an occluded pancreatic duct will frequently not improve over time, pseudocysts that arise in this setting and are symptomatic will frequently require treatment.

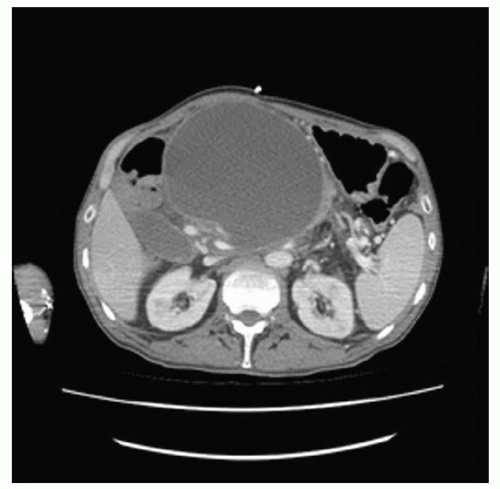

Figure 12.1 A: CT scan demonstrating an acute fluid collection associated with acute interstitial pancreatitis. B: CT showing a well-circumscribed, large pseudocyst containing homogeneous fluid. |

Although pseudocyst size may be an important determinant of treatment, symptoms that result from pseudocysts are frequently the result of adjacent organ compromise. Pseudocysts located in the head of the pancreas may cause gastroduodenal obstruction and may be associated with the development of nausea, vomiting, or early satiety. Similarly, relatively small but precisely located pseudocysts in the head of the gland

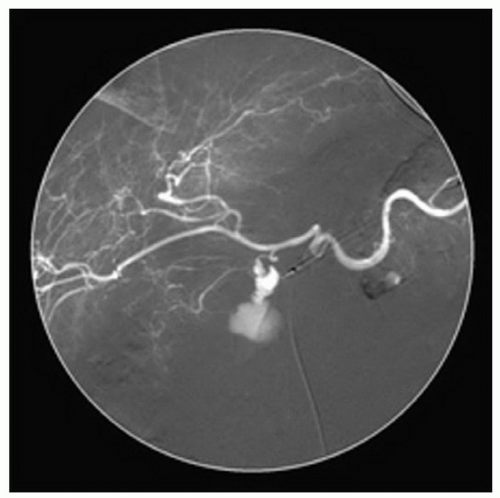

may obstruct the biliary tract and result in jaundice, pruritus, and other symptoms of cholestasis. Importantly, a relatively large pseudocyst in the body and/or tail of the gland may cause few noticeable symptoms but result in compression or thrombosis of the mesenteric, portal, and/or splenic venous systems. The indolent, but potentially devastating consequences, of pseudocyst formation and location on nearby vascular structures, such as arterial pseudoaneurysm formation, must be recognized (Fig. 12.2). In addition, infection of a pancreatic pseudocyst requires prompt treatment to prevent systemic sepsis and rupture of a pancreatic pseudocyst, though rare, requires appropriate recognition and treatment.

may obstruct the biliary tract and result in jaundice, pruritus, and other symptoms of cholestasis. Importantly, a relatively large pseudocyst in the body and/or tail of the gland may cause few noticeable symptoms but result in compression or thrombosis of the mesenteric, portal, and/or splenic venous systems. The indolent, but potentially devastating consequences, of pseudocyst formation and location on nearby vascular structures, such as arterial pseudoaneurysm formation, must be recognized (Fig. 12.2). In addition, infection of a pancreatic pseudocyst requires prompt treatment to prevent systemic sepsis and rupture of a pancreatic pseudocyst, though rare, requires appropriate recognition and treatment.

Figure 12.2 Visceral angiogram of celiac access demonstrating bleeding from an arterial pseudoaneurysm that complicated pancreatitis with pseudocyst formation. |

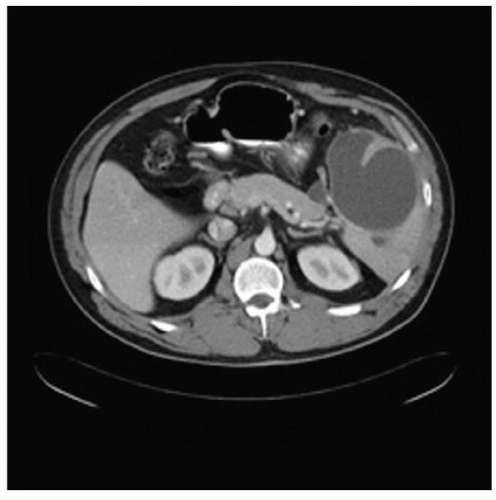

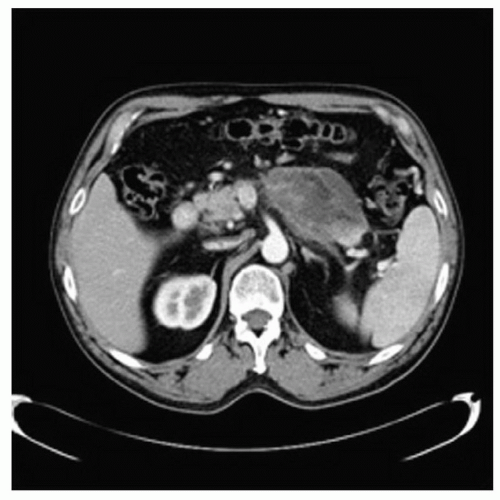

Some pancreatic pseudocysts require special consideration including those defined as huge (>15 cm; Fig. 12.3), arising primarily in the spleen (Fig. 12.4), and associated

with the disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome (Fig. 12.5). Pseudocysts with these features should be recognized and treated appropriately. Treatment of these pseudocysts with special considerations will be detailed later in the chapter.

with the disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome (Fig. 12.5). Pseudocysts with these features should be recognized and treated appropriately. Treatment of these pseudocysts with special considerations will be detailed later in the chapter.

Figure 12.4 CT findings include a tiny pseudocyst in the tail of the pancreas with a large, primarily intrasplenic, pseudocyst. |

Figure 12.5 CT showing a disconnected pancreatic duct with a small tail of viable pancreas separated from the body of the gland by an evolving pseudocyst. |

Perhaps, more important than the pseudocysts that require treatment are those that do not require therapy. Notably, as mentioned previously, acute fluid collections must be distinguished from pseudocysts and these should not be treated as they will resolve spontaneously. Previously, size was an important determinant of treatment; however, recent work suggests that pseudocysts less than 6 cm in size rarely cause complications and treatment is not required. Conversely, pseudocysts greater than 10 cm in size do not necessarily require therapy if they do not cause symptoms. However, pseudocysts this large frequently cause insidious problems and no longterm data with significant numbers of patients document the safety of an observational approach in these patients.

The differential diagnosis of cystic lesions of the pancreas is delineated in Table 12.1.

TABLE 12.1 Differential Diagnosis of Cystic Lesions of the Pancreas Exclusive of Pancreatic Pseudocysts | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNINGPreoperative assessment and planning the management of patients with pseudocysts require establishing the cause of pseudocyst formation. Obtaining a careful history is important to determine if a pseudocyst is a consequence of acute pancreatitis that was caused by gallstones, ethanol consumption, or otherwise. Likewise, establishing a diagnosis of alcohol-related chronic pancreatitis is germane to the treatment of pseudocysts since continued use of ethanol may be associated with progressive disease and recurrence. Moreover, the presence of associated symptoms that suggest an alternative diagnosis such as a pancreatic tumor or a long-standing pancreatic disease should be ascertained. These symptoms include weight loss, jaundice, pruritus, acholic stool, dark urine, steatorrhea, the recent onset of diabetes mellitus, or, rarely, skin manifestations.

Because of the deep, retroperitoneal location of the pancreas, physical examination rarely results in palpation of a pseudocyst and only the most gravely ill patients with acute pancreatitis exhibit features of the disease that are evident on examination. In a similar fashion, laboratory evaluation is almost never diagnostic and likely is most useful in suggesting alternative diagnoses such as pancreatic cancer in a patient with a markedly increased CA 19-9 concentration.

Imaging of the pancreas and surrounding structures, however, is of paramount importance. Typically, cross-sectional imaging with thin-slice computed tomography (CT) is the preferred modality for many surgeons. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), especially when accompanied by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), may also be a useful diagnostic tool that provides valuable information and has some advantages over CT in institutions with specific MRI-related expertise. Regardless, precise imaging of the pancreatic parenchyma and duct, associated pseudocyst, adjacent organs, and surrounding vascular structures is critically important to operative planning. Importantly, when CT is the preferred imaging, a triple phase scan that demonstrates the arterial blood supply and the venous drainage of the pancreas should be critically examined. Needless to say, cross-sectional imaging provides a necessary roadmap for surgical management.

Pancreatography is as important as meticulous cross-sectional imaging in many patients. Essentially, all patients with chronic pancreatitis require endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) to define pancreatic ductal anatomy and to determine the presence of a clinically asymptomatic biliary stricture. Pancreatography may identify pancreatic duct strictures or stenoses, communication with the pseudocyst, and duct cut-offs, all of which are important to recognize prior to surgical treatment. Pancreatic ductal anatomy often determines the operative procedure and the outcome. Though pancreatography is not required for all patients with acute pancreatitis-induced ductal disruptions, it should be contemplated in each patient that requires treatment since a pseudocyst resulting from a disruption in an otherwise normal duct may be treated by transpapillary duct stenting. In addition, ERCP may be helpful to detect otherwise unappreciated ductal changes induced by acute pancreatitis.

The outcome of surgical management is often determined by careful preoperative assessment including a complete history, imaging, and pancreatography. Detailed assessment and preoperative planning is requisite for an optimal outcome.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE