Excellent or good bowel preparation

Straight colon

Cooperative patient

No proximal colon cancer

Relatively fit patient with life expectancy >3 years

Controlling the Colonoscope

Control of the colonoscope is an important part of safe polypectomy technique. Ideally the scope should be straight, so that there is “one-to-one” movement of the tip of the scope. If there is a loop, the tip of the scope is hard to stabilize, and moving the scope in or out produces unpredictable results at its tip. The scope can suddenly straighten and lose position. When this happens with a snare around a polyp, the outcome can be disastrous.

Another benefit of a straight scope is that it allows easy rotation to position the polyp in the most favorable position for snaring. This is at “6 o’clock,” where the therapeutic channel is located. A straight scope also facilitates retroversion of the tip, an important part of technique for dealing with polyps on the reverse side of a fold. Finally, a straight scope means a more comfortable patient and one who is more likely to be cooperative. Therefore, insertion technique should produce a straight scope to the cecum. Polypectomy should usually be performed during scope withdrawal, when the scope is straight.

Piecemeal or En Bloc

Jerry Waye has advised that the maximum “bite” that should be removed during one application of the snare is 2 cm [16]. Larger bites can pull in deeper layers of the colon wall and can transect larger arteries with less efficient coagulation. This is good advice. However, it means that sessile polyps over 2 cm in diameter have to be removed piecemeal. This has been designated as the main disadvantage of conventional polypectomy and a reason why large polyps should be removed by endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection. The downsides of piecemeal polypectomy are that some polyp may be left behind, that margins of resection are difficult to determine, and that not all pieces may be recovered for histology. The upside is safety. For the average colonoscopist, piecemeal polypectomy is an effective way of treating large sessile lesions, and the theoretical disadvantages do not usually translate into practical problems.

Snaring the Difficult Lesion

Pedunculated Polyps

The basic technique for snaring any pedunculated polyp is simple: a snare is passed over the head of the polyp and tightened around the stalk. The stalk is coagulated and transected.

Choice of snare is important. Snare diameters vary from 1.5 cm (mini) through 2.0 cm (standard) to 3.0 cm (jumbo). In addition snares may be oval, crescentic or hexagonal, smooth or barbed, equipped with electrocautery (hot) or not (cold), and rotatable or fixed. For a pedunculated polyp, an oval, hot snare of appropriate size is passed over the head of the polyp and tightened around the stalk, ideally a millimeter or two below the junction of the head and the stalk. As the snare is tightened, bursts of coagulation current are applied. (It is my practice to use pure coagulation current, in bursts of one or two seconds. Others use blended cut and coagulation.) The stalk is transected. Ideally this should all be under direct vision, but difficult polyps may be so large as to fill the lumen of the colon (especially in the sigmoid), making the stalk difficult to see. They may be too large for the snare to encompass or they may be too mobile to pin down. Finally the stalk may be wide and scary (Fig. 2.1a, b).

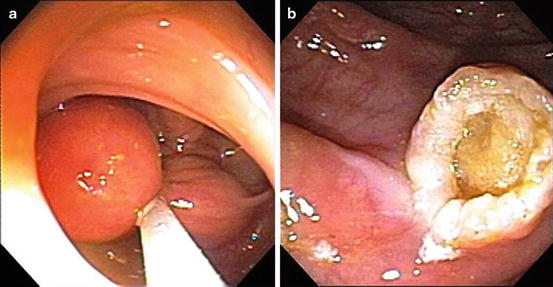

Fig. 2.1

(a) Snare around a pedunculated sigmoid lipomas. (b) Stalk after snaring a pedunculated sigmoid lipoma

For successful and safe polypectomy, the stalk must first be recognized. The scope is pushed past the polyp, and during this process it is usually possible to see a stalk. The mobility of the polyp is a secondary indication of the presence of a stalk.

Changing patient position is a good way of improving access to the polyp. Rotating the colonoscope also helps. Patience and a willingness to try various positions are key to successful demonstration of a difficult polyp and its stalk. The snare can then be passed over the head of the polyp. If the polyp is large, the snare can be expanded by opening it against the wall of the colon. It can then be worked down toward the junction of the head with the stalk. The stalk can then be slowly transected. The endoscopy assistant can assess the thickness of the tissue contained within the snare and make sure it matches the thickness of the stalk seen on the screen. The stalk can be clipped either before or after transection or injected with adrenaline either before or after (Fig. 2.2).

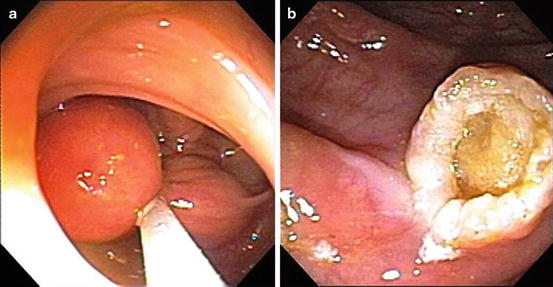

Fig. 2.2

Injection of the stalk of a pedunculated adenoma before snaring

Sessile/Flat Polyps

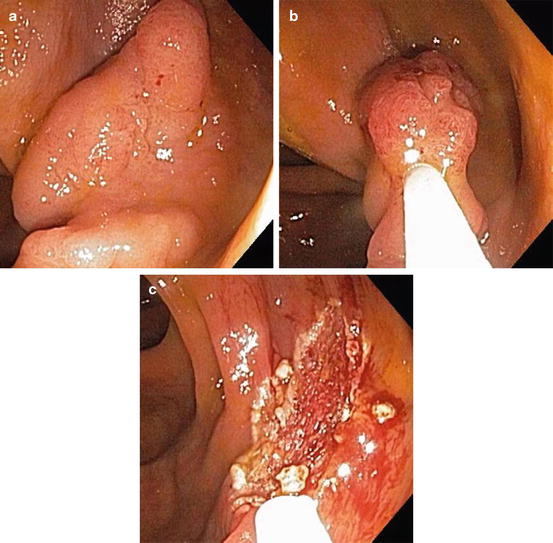

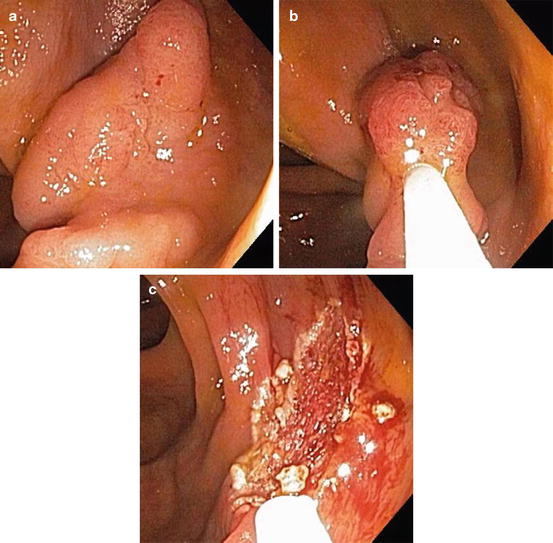

Snaring large sessile polyps poses a different set of challenges. While the polyps rarely obliterate the lumen and are easier to see, they may overlap haustral folds and may be of a low enough profile to make snaring difficult. The best snare for these lesions is a large, hexagonal snare. The polyp is positioned at 6 o’clock, and the snare opened over the part of the polyp that comes most easily to view. The snare sheath is placed just proximal to the polyp and pushed down toward the bowel wall. This levers the polyp up into the loop of the snare. Suction will further pull the polyp up into the snare loop, and a few wiggles can consolidate this even further. The snare is then tightened gradually until it is tight around the polyp. The endoscopist is careful to see that minimal normal mucosa is enclosed in the snare and that no more than 2 cm of polyp is trapped. Using pure coagulation current applied in short bursts, the snare is closed. Sometimes it takes a few seconds and several bursts of current for the polyp to be transected. Patience and a stout heart may be required. When the polyp starts to shake, this is a sign that transection is imminent (Fig. 2.3a–c).

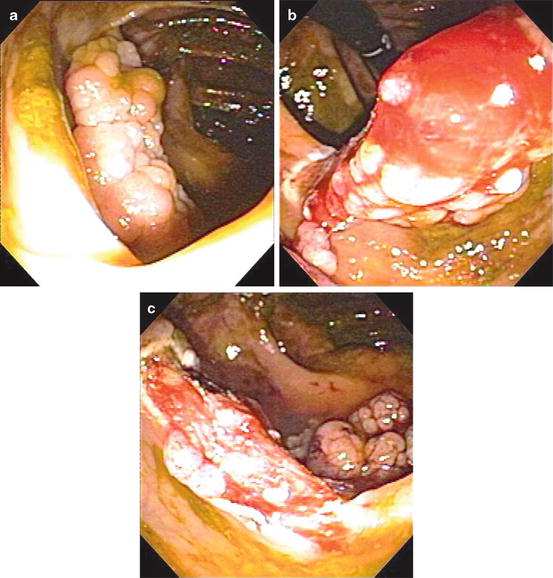

Fig. 2.3

(a) Medium-sized sessile polyp in the ascending colon. (b) Snare placed around the polyp. (c) Polypectomy complete

If the snare keeps sliding off the polyp, the polyp may be injected with submucosal saline in one corner, which may raise the lesion enough for the snare to stick. Alternatively, a corner of the polyp can be coagulated with hot biopsy forceps. The coagulation and the associated edema raise the lesion so that the snare will grip. A barbed snare may be useful here. Once one corner has been snared, the incision line makes it easier for the remaining polyp to be snared. Very large sessile polyps should be snared in pieces starting with the most prominent part. The rest of the polyp is then systematically removed. These techniques can be applied to flat lesions.

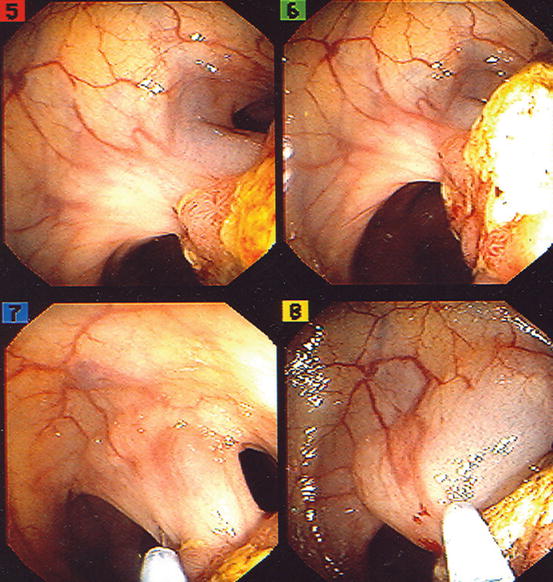

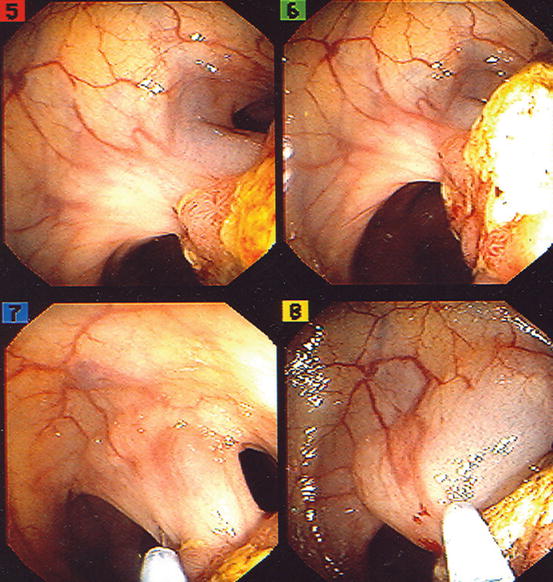

Polyps Over a Fold

Polyps on or over a fold are snared as described above. The snare sheath can be used to flatten the fold. Often, during the course of the polypectomy, the colon contracts and flattens the fold spontaneously or pushes the polyp forward. Although such moments are fleeting, they are an opportunity to place the snare effectively. Polyps on the backside of a fold are most difficult and can sometimes be managed by retroflexion of the scope. This is handy for polyps on the underside of the ileocecal valve, with retroflexion in the cecum, or on the underside of folds in the ascending colon and hepatic flexure. The right colon is capacious enough to allow easy retroflexion, especially if a pediatric scope is used (Fig. 2.4a–c). An alternative for polyps draped over a fold is to raise them by submucosal saline injection distally. Also, the fold can be flattened by pushing down with the snare sheath or by changing patient position. Begin polypectomy with the part behind the fold.