Debridement for Pancreatic Necrosis

Karen Horvath

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONSIntroduction

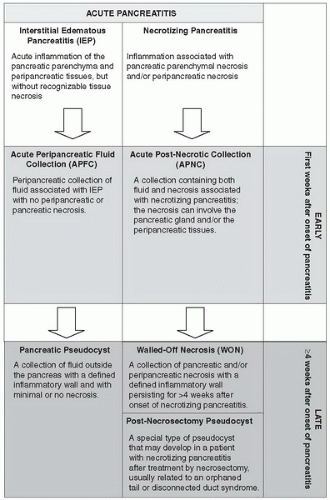

There are approximately 210,000 cases of acute pancreatitis per year in the United States. Ninety percent of patients will have a mild form of interstitial edematous pancreatitis, but about 10% will develop severe acute pancreatitis. Some patients will develop acute peripancreatic fluid collections (APFC) that will resolve with medical support alone or will go on to develop a pancreatic pseudocyst (Chapter 12). The subject of this chapter concerns those patients who develop necrotizing pancreatitis. These patients develop acute post-necrotic collections (APNC) involving necrosis of the pancreatic parenchyma and the peripancreatic tissues, the pancreatic parenchyma alone, or the peripancreatic tissue alone. When APNC persists beyond 4 weeks from the onset of pancreatitis, the term walled-off necrosis (WON) can be applied. These terms represent morphologic abnormalities noted on contrast-enhanced CT scan that are used for classification purposes and to guide treatment (Fig. 8.1).

When treating patients with necrotizing pancreatitis it is important to be cognizant of the time from onset of symptoms since recent data demonstrates that delayed intervention leads to lower morbidity and mortality rates. Over a four-week period, APNC’s evolve: the peripancreatic tissue inflammation subsides, the tissue within the collection demarcates into viable and non-viable components and the perimeter of the collection matures into the defined wall of WON. A distinction should also be made between sterile and infected necrosis, since the presence of infection means a different prognosis, natural history and approach to treatment. Patients with sterile WON will usually resolve over time without any intervention. In fact, a percutaneous drain should generally not be placed into sterile collections unless there is a very good indication since it will iatrogenically infect the collection after a short time and complicate the patient’s management. A small subset of patients with sterile WON will require pancreatic necrosectomy either because of persistent symptoms such as anorexia, early satiety, vomiting, pain, fever, or failure to thrive. All patients with WON who become infected require treatment with parenteral antibiotics in combination with effective drainage/necrosectomy.

Infection develops in 30% to 70% of patients with necrotizing pancreatitis and accounts for more than 80% of deaths from acute pancreatitis. The risk of infection increases with the amount of pancreatic glandular necrosis and the time from the onset of acute pancreatitis, peaking at 3 weeks. Infection is presumed when there is gas present in the WON on CT scan. It is also diagnosed definitively with an image-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) showing a positive Gram stain and culture. Since patients carry a significant risk of converting from sterile to infected tissue over time, patients should be followed closely and an FNA performed if clinically indicated with a change in abdominal pain, fever, or leukocytosis. Since FNA has a false-negative rate of about 10%, a negative FNA may be repeated after appropriate intervals, such as 5 to 7 days, if a clinical suspicion of infection persists. FNA has a low iatrogenic infection rate along with a high sensitivity and specificity.

Once the patient is determined to be infected, they require complete external drainage or face a near 100% mortality. While deciding amongst percutaneous, laparoscopic, endoscopic, or open surgical options, a percutaneous drain should be placed within

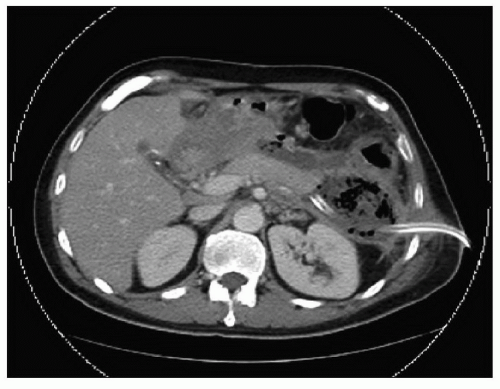

24 hours of a positive FNA to initiate external drainage (Fig. 8.2). Once a percutaneous drain has been placed, we aggressively upsize the catheters every 3 to 4 days to an 18-20Fr goal. A CT is repeated about 2 weeks after the first drain was placed. If the patient has a remaining large collection and at least 4 weeks have elapsed since onset of disease, plans are made for surgery. In general, surgery for APNC should be delayed until the WON phase due to lower morbidity and mortality. While waiting for this safer time, sepsis control can be temporized with percutaneous drains and when necessary, the addition of parental antibiotics. Careful attention must be paid to the protein and calorie requirements in these patients which are very high. Most patients are unable to consume their total caloric needs and almost all will require supplemental enteral or parenteral nutrition and close monitoring of their nutritional status with serum markers. Enteral nutrition (nasogastric or nasojejunal) is the preferred route when tolerated, since it has been shown to be associated with significant decreases in the risk of pancreatitis associated morbidity and mortality.

24 hours of a positive FNA to initiate external drainage (Fig. 8.2). Once a percutaneous drain has been placed, we aggressively upsize the catheters every 3 to 4 days to an 18-20Fr goal. A CT is repeated about 2 weeks after the first drain was placed. If the patient has a remaining large collection and at least 4 weeks have elapsed since onset of disease, plans are made for surgery. In general, surgery for APNC should be delayed until the WON phase due to lower morbidity and mortality. While waiting for this safer time, sepsis control can be temporized with percutaneous drains and when necessary, the addition of parental antibiotics. Careful attention must be paid to the protein and calorie requirements in these patients which are very high. Most patients are unable to consume their total caloric needs and almost all will require supplemental enteral or parenteral nutrition and close monitoring of their nutritional status with serum markers. Enteral nutrition (nasogastric or nasojejunal) is the preferred route when tolerated, since it has been shown to be associated with significant decreases in the risk of pancreatitis associated morbidity and mortality.

Figure 8.2 Contrast-enhanced CT scan of a patient with infected WON. A percutaneous drain is present in the collection. |

A small subset of necrotizing pancreatitis patients will require emergent surgery for organ failure and acute decompensation due to an intra-abdominal catastrophe such as visceral ischemia. Acute decompensation is most often due to a reactivation of the SIRS response or a non-surgical source of infection. Because of this, intensive support should be given for 24 to 48 hours along with a search for the cause, but if an intra-abdominal catastrophe is suspected the patient will need an emergency laparotomy.

Indications for Surgery

Severe acute pancreatitis with APFC or APNC, less than 30 days from the onset of pancreatitis, with organ failure and suspected intra-abdominal catastrophe unresponsive to 24 to 48 hours of intensive support.

WON, by definition greater than 30 days from the onset of necrotizing pancreatitis, that is:

Infected, with infection documented by gas seen in the collection on contrastenhanced CT scan or with a positive FNA.

Sterile but symptomatic.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNINGThere are many excellent surgical options for pancreatic debridement. Transgastric endoscopic methods and percutaneous drains can also be used as primary or adjunctive methods. Minimally invasive methods are increasingly being used as a first step for operative necrosectomy in patients with infected WON with open necrosectomy

reserved for patients who fail minimal access techniques or require an emergent exploration. The three most popular minimally invasive retroperitoneal debridement methods are:

reserved for patients who fail minimal access techniques or require an emergent exploration. The three most popular minimally invasive retroperitoneal debridement methods are:

Step-Up Approach consisting of percutaneous drainage followed by Videoscopic-assisted retroperitoneal debridement (VARD)

Percutaneous Necrosectomy

Minimal Access Retroperitoneal Pancreatic Necrosectomy (MARPN)

There are four methods for open surgical necrosectomy:

Necrosectomy followed by continuous postoperative lavage.

Conventional drainage with placement of standard surgical drains and reoperation as needed.

Open management technique with necrosectomy followed by scheduled relaparotomies through a marsupialized open abdomen.

Open retroperitoneal approach through the base of the 12th rib.

The two techniques described here will be the Step-Up Approach which now has phase I feasibility, phase II safety and efficacy, and phase III randomized controlled data supporting its use and open necrosectomy followed by continuous postoperative lavage which is the open method upon which VARD is based.

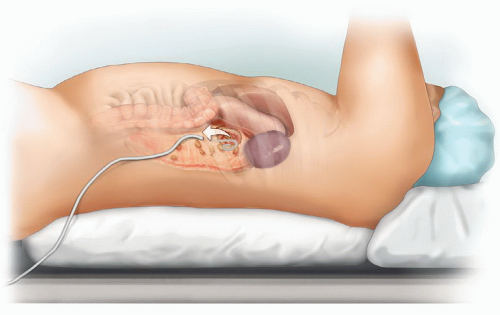

Once the patient with a WON is determined to be infected a percutaneous drain is placed. If this drain is not effective a VARD will be needed. The patient will need a minimum of one percutaneous drain placed into the collection from the flank, to be used as an intraoperative guide. When doing the VARD procedure, the surgeon follows the path of this drain through the retroperitoneum and into the collection. Even if another drain is already in place, it is important for the interventional radiologist to place a drain as close as possible to the left mid-axillary line just under the costal margin for operative guidance (Fig. 8.3). A CT scan should be repeated showing this drain in place and a hard copy made for use in the OR. The position of this drain inside the collection and its location to nearby anatomical structures will be used in the OR by the surgeon to guide operative debridement. Necessary OR equipment is shown in Table 8.1.

All patients with necrotizing pancreatitis should have an ultrasound of the gall bladder performed. If gallstones or sludge are present, a cholecystectomy should be planned. Patients undergoing a VARD should have a laparoscopic cholecystectomy within 6 months following complete resolution of the peripancreatic collections and inflammatory process. Patients undergoing an open necrosectomy may have a cholecystectomy attempted at the time of their surgery; however, it may not be possible to perform a safe cholecystectomy when there is a large amount of necrosis because of significant inflammation in the porta hepatis.

Figure 8.3 Percutaneous drain entering flank near mid-axillary line under left costal margin to be used as an operative guide into the collection. |

TABLE 8.1 Necessary OR Equipment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

SURGICAL TECHNIQUEPertinent Anatomy and General Operative Principles

The pancreas is a retroperitoneal organ and the areas of WON almost always respect this anatomic compartmental boundaries. Whether the collections extend down the paracolic gutters and into the pelvis or into the leaves of the small or large bowel mesenteries, the collections usually remain bounded by peritoneum. Some patients may also develop ascites but this is most often a separate, sterile process. Thus, the overarching goal of any pancreatic debridement procedure should be to limit intrusion into the peritoneal cavity and protect the visceral contents from infection and injury as much as possible. Another important operative principle for pancreatic necrosectomy follows the dictum, “Perfect is the enemy of good.” The goal of a necrosectomy is to break up loculations and debride large pieces of necrotic tissue but not

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree