Richard Edward Link, MD, PhD

Introduction to Basic Dermatology

Literally hundreds of cutaneous diseases exist involving the external genitalia. In addition, within each disease there may be significant variation in appearance and symptoms as the process evolves. For this reason, a methodical and systematic approach is essential to reach a rational diagnosis. The dermatologic history should focus on the duration, rate of onset, location, symptoms, family history, allergies, occupation, and previous treatment of the condition (Habif, 2004). Common symptoms include pruritus (itching), burning, and pain.

The physical examination should address the distribution of primary and secondary skin lesions. It is important to perform a thorough skin survey and not focus solely on the area of affected genital skin. Most skin conditions begin with a characteristic primary lesion that is an important key to diagnosis. Precise description of this lesion includes documenting its color (red, brown, black, yellow, blue, or green) and morphology (macule, papule, plaque, nodule, pustule, vesicle, bulla, or wheal; Table 15–1) (Habif, 2004). Because of the mucosal nature of genital skin, papular and macular lesions may present as erosions in this area (Margolis, 2002). Secondary skin lesions develop as the skin condition evolves or are caused by scratching or superinfection. A secondary lesion should also be classified morphologically as a scale, crust, erosion, ulcer, atrophy, or scar (Table 15–2).

Table 15–1 Primary Cutaneous Lesions

| PRIMARY LESION | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Flat | |

| Macule | A circumscribed, flat discoloration that may be brown, blue, red, or hypopigmented |

| Elevated Solid | |

| Papule | An elevated, solid lesion up to 0.5 cm in diameter of variable color. Papules may become confluent to become plaques |

| Nodule | A circumscribed, elevated solid lesion >0.5 cm in diameter |

| Plaque | A circumscribed, elevated, superficial, solid lesion >0.5 cm in diameter |

| Fluid-Filled | |

| Vesicle | A circumscribed collection of free fluid up to 0.5 cm in diameter |

| Bulla | A circumscribed collection of free fluid >0.5 cm in diameter |

| Pustule | A circumscribed collection of leukocytes and free fluid (pus) |

| Wheal (hive) | A firm erythematous plaque resulting from infiltration of the dermis with fluid (may be transient) |

From Habif TP. Clinical dermatology: a color guide to diagnosis and therapy. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2004.

Table 15–2 Secondary Cutaneous Lesions

| SECONDARY LESION | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Scale | Excess dead epidermal cells that are produced by abnormal keratinization and shedding |

| Crust | A collection of dried serum and cellular debris (a scab) |

| Erosion | A focal loss of epidermis. Erosions do not penetrate below the dermoepidermal junction and heal without scarring |

| Ulcer | A focal loss of epidermis and dermis which heals with scarring |

| Fissure | A linear loss of epidermis and dermis with sharply defined, vertical walls |

| Atrophy | A depression in the skin resulting from thinning of the epidermis or dermis |

| Scar | An abnormal formation of connective tissue implying dermal damage |

From Habif TP. Clinical dermatology: a color guide to diagnosis and therapy. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2004.

Dermatologic Therapy

A lack of familiarity with cutaneous diseases affecting the genitalia may lower the threshold that leads urologists to prescribe systemic antibiotics for these conditions. Unfortunately, these agents carry significant greater risks than topical preparations, including promotion of resistant organisms, interaction with other medications, and disruption of the normal bowel and vaginal flora. Similar caveats apply to systemic antifungal agents such as ketoconazole and fluconazole. Superficial dermatophytes, such as those causing tinea cruris, generally respond well to topical antifungal preparations. Systemic antifungals are indicated for local infection with an extensive area of skin involved, disseminated mycoses with skin involvement, infection involving the hair follicles, or fungal infections in immunocompromised individuals (Lesher and McConnell, 2003). In some cases, even in immunocompetent individuals, systemic antifungals are necessary to treat infections resistant to local therapy (Lesher, 1999).

Systemic anti-inflammatory agents, particularly the glucocorticosteroids (GCS), deserve additional attention. Oral GCS are absorbed in the jejunum, with peak plasma concentrations occurring in 30 to 90 minutes (Lester, 1989). Despite short plasma half-lives of 1 to 5 hours, the duration of effect of GCS lasts between 8 and 48 hours, depending on the agent (Nesbitt, 2003). These drugs have widespread anti-inflammatory effects. They release neutrophils from bone marrow but inhibit their movement to sites of inflammation in tissue. They also impair both T-cell activation and antigen presentation by dendritic cells (Nesbitt, 2003). For short-term (≤3 weeks) treatment of dermatologic conditions such as allergic contact dermatitis (Feldman, 1992), a single morning dose of GCS is given to minimize suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (Myles, 1971). Prednisone is generally the GCS of choice due to its low cost, intermediate duration of action, and variety of dosage forms, although methylprednisolone may be substituted to reduce mineralocorticoid effects (Wolverton, 2001). Longer-term treatment with systemic GCS may lead to a wide variety of adverse effects, including osteoporosis, cataract formation, hypertension, obesity, immunosuppression, and psychiatric changes (Nesbitt, 2003).

Topical preparations have both active ingredients and a vehicle, which determines the rate at which the active ingredients are absorbed by the skin. Emollients restore water and lipids to the epidermis and are useful for dry skin diseases. Emollients should be applied to moist skin for maximal effect, such as after bathing. Preparations containing urea (e.g., Carmol, vanodine) or lactic acid (Lac-Hydrin, AmLactin) may be particularly potent hydrating agents (Habif, 2004).

Topical corticosteroids are potent anti-inflammatory agents available in a myriad of preparations and strengths. A detailed review of the use and dosing of topical corticosteroids is beyond the scope of this chapter, and the reader is directed to several excellent dermatology textbooks for more detail (Habif, 2004). It is important to recognize that even topical corticosteroids can have significant adverse effects, from both systemic and local absorption. Local effects include epidermal atrophy, dermal changes (telangiectasias, hypopigmentation), allergic reactions, and alteration in the usual course of skin infections and infestations (Burry, 1973). In most cases, atrophy is a reversible process that can be expected to resolve over the course of several months (Sneddon, 1976). Atrophy is particularly troublesome if corticosteroids are applied under the foreskin, which can serve as an occlusive “dressing” and enhance penetration of the drug (Fig. 15–1) (Goldman and Kitzmiller, 1973).

Figure 15–1 Steroid atrophy of penile shaft skin after application of corticosteroid under the foreskin for 8 weeks.

(From Habif TP. Clinical dermatology. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2004. p. 36.)

A variety of physical modalities have also been applied to treat dermatologic problems, including ultraviolet light therapy, photodynamic therapy, laser therapy, and cryosurgery. Ultraviolet light therapy with UVB has been used to treat psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and seborrheic dermatitis (Honigsmann and Schwarz, 2003). Psoralens, when combined with long-wave UVA radiation (PUVA therapy), generate a phototoxic effect beneficial for treating psoriasis (Honigsmann, 2001; Stern, 2007), vitiligo (Honigsmann and Schwarz, 2003), atopic dermatitis (Morison, 1992), and lichen planus (Honigsmann and Schwarz, 2003). Photodynamic therapy (PDT) involves the use of cytotoxic oxygen radicals generated from photoactivated molecules to achieve a therapeutic response (Tope and Shaffer, 2003; Braathen et al, 2007). PDT is a new arena of dermatologic therapy and holds promise for treating a variety of inflammatory and malignant skin conditions. Laser and cryosurgery play a relatively small role in the management of genital lesions, although the CO2 laser has been used effectively to manage genital condyloma acuminata.

Allergic Dermatitis

Allergic or “eczematous” dermatitis consists of a group of allergy-mediated processes leading to pruritic skin lesions (Table 15–3).

Table 15–3 Differential Diagnosis of Allergic Dermatitis

From Margolis DJ. Cutaneous disease of the male external genitalia. In: Walsh PC, editor. Campbell’s urology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002.

Atopic Dermatitis (Eczema)

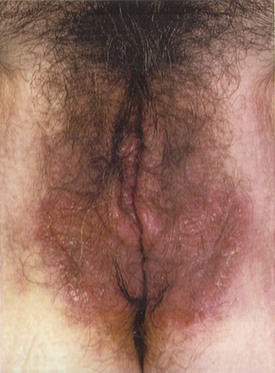

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic relapsing dermatitis with a predilection for skin flexures that is associated with intense pruritus and damage to the epidermis (Williams, 2005). The characteristic lesions are erythematous papules and thin plaques with secondary excoriations (Fig. 15–2) (Kang et al, 2003). In general, the lesions do not have a precise border as is common for papulosquamous disorders (Margolis, 2002). Although any age can be affected, 90% of AD patients manifest their condition before the age of 5 years (Rajka, 1989). AD is associated with susceptibility to irritants and proteins as well as the tendency to develop asthma and allergic rhinitis.

Figure 15–2 Eczema involving the vulva.

(From du Vivier A. Atlas of clinical dermatology. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2002. p. 687.)

The genetic susceptibility to AD has been extensively explored. In a study of 372 AD patients, 73% had a positive family history for atopy. Likewise, twin concordance studies have demonstrated a risk of 0.86 for monozygotic twins to have AD as compared with only 0.21 for dizygotic twins. These findings have spurred an intense search for genes involved in atopy and AD (Wollenberg and Bieber, 2000), although, to date no single gene serves as a unique marker for the disease (Kang et al, 2003).

Intense pruritus is the hallmark of AD, and controlling the patient’s urge to scratch is critical for successful treatment (Przybilla et al, 1994). Itching is often worse during evening hours and can be exacerbated by sweat or wool clothing (Kang et al, 2003). Scratching of lesions may contribute to the clinical complications of AD, including superinfection with Staphylococcus aureus species (Ogawa et al, 1994). There is growing evidence that bacterial toxins may serve as superantigens that drive an inflammatory cascade sustaining AD (Skov and Baadsgaard, 2000; Skov et al, 2000).

Clinically, there is no pathognomonic laboratory test, biopsy result, or single clinical feature that allows the definitive diagnosis of AD. The association with a personal or family history of atopy is a critical clue to the diagnosis (Kang et al, 2003). For patients presenting with genital findings, extragenital involvement is commonplace.

A variety of “trigger factors” have been implicated in the exacerbation of AD, including chemicals, detergents, and household dust mites. Removal of these factors from the environment may be beneficial on an individualized basis. Dust mite exposure, in particular, has received significant attention in the literature. Although several studies have demonstrated modest improvement in AD with mite reduction (Kubota et al, 1992; Tan et al, 1996), others report that reduction is associated with no significant clinical benefit (Colloff et al, 1989; Gutgesell et al, 2001).

Treatments for AD include gentle cleaning with nonalkali soaps and the frequent use of emollients. Evaporation of liquid from the skin may trigger AD (Kang et al, 2003); thus very frequent bathing is not encouraged. Soaking may be helpful during episodes of bacterial super-infection but should be discontinued once the infection has resolved (Margolis, 2002). Topical corticosteroids may be needed to control pruritus but should only be used for short courses with a rapid taper to avoid local complications of skin atrophy and pigment changes. Topical macrolide immunomodulatory agents such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus have shown efficacy in the treatment of AD (Meagher, et al, 2002; Nghiem et al, 2002; Luger and Paul, 2007; Leung et al, 2009), and may decrease the need for corticosteroids during long-term therapy (Zuberbier et al, 2007). Antihistamines such as diphenhydramine may be helpful in breaking the “itch-scratch cycle” in AD, particularly when given before bedtime (Kang et al, 2003). Oral antistaphylococcal drugs have not been shown to significantly improve AD in a recent randomized, double-blind trial (Ewing et al, 1998). Systemic treatment with corticosteroids, cyclosporine, methotrexate, or azathioprine may be indicated rarely for severe, widely disseminated cases (Cooper, 1993; Salek et al, 1993).

Contact Dermatitis

ICD results from a direct cytotoxic effect of an irritant chemical touching the skin and is responsible for approximately 80% of contact dermatitis cases (Marks et al, 2002). Examples of offending agents include soaps, solvents, metal salts, and acid- or alkali-containing compounds. Occupational ICD is a serious public health problem and contributes to costs on the scale of $1 billion annually in the United States (Cohen, 2000). The clinical manifestations of ICD depend on the identity of the irritating substance as well as the duration of contact, concentration, temperature, pH, and location of exposure. Acute ICD, such as might be result from an occupational accident, generally peaks within minutes to hours after exposure and then begins to heal. Symptoms of burning, stinging, and soreness may be accompanied by erythema, edema, bullae, or frank necrosis in a sharply defined area corresponding to the exposed skin (Cohen and Bassiri-Tehrani, 2003). There are also a variety of subacute forms of ICD that result from repeated subthreshold skin insults. Pruritus is much more common in these more chronic conditions and the skin lesions are less well demarcated. The mainstay of treatment for ICD lies in avoiding skin contact with the causative irritants through the use of protective clothing, safe occupational practices, and the use of skin barriers such as ointments or emollients (Berndt et al, 2000).

In contrast, allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) represents a local type IV hypersensitivity reaction to a skin allergen to which an individual has been previously sensitized. The typical appearance is a well-demarcated pruritic eruption, which may manifest blistering or weeping in the acute phase or the development of scaly plaques more chronically (Mowad and Marks, 2003). In 2003 and 2009, the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) reported a long list of common allergens implicated in ACD based on patch testing results (Zug et al, 2009). Patch testing is a simple technique of exposing an area of skin to a variety of potential allergens in a grid template (Fig. 15–3). Generally performed by dermatologists, patch testing can help to confirm the diagnosis of ACD and the allergen involved. The most common sensitizing allergen identified by the NACDG was nickel sulfate (Zug et al, 2009), which is a common component of costume jewelry and belt buckles (Fig. 15–4). Although traditionally a cause of earlobe dermatitis from pierced earrings, nickel sensitivity may be a potential cause of genital ACD due to the increasing prevalence of genital piercing. Other important allergens include textile dyes, topical antibiotics, perfumes, and topical corticosteroids. Oral antihistamines may be helpful for the symptomatic control of ACD in combination with removal of the inciting allergen.

Figure 15–3 An example of patch testing with a positive response to nickel.

(From Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2003. p. 233.)

Figure 15–4 Contact dermatitis from belt buckle due to nickel allergy.

(From Habif TP. Clinical dermatology, Edinburgh: Mosby; 2004. p. 94.)

Erythema Multiforme and Stephens-Johnson Syndrome

EM minor was first described in 1860 by an Austrian dermatologist, Ferdinand von Hebra (von Hebra, 1860). It is an acute, self-limited skin disease characterized by the abrupt onset of symmetrical fixed red papules that may evolve into target lesions (Weston, 1996). EM is a clinical rather than a histologic diagnosis. Papules and target lesions are usually grouped and can be present anywhere on the body, including the genitalia (Fig. 15–5A). There is also a predilection for involvement of the oral mucous membranes.

(A, From Korting GW. Practical dermatology of the genital region. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1981. p. 16; B, from Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. Edinburgh: WB Saunders; 2009. p. 147.)

The majority of cases of EM minor are precipitated by herpesvirus type I and II (Schofield et al, 1993; Nikkels and Pierard, 2002), with herpetic lesions usually preceding the development of target lesions by 10 to 14 days (Lemak et al, 1986). Although continuous suppressive acyclovir may prevent EM episodes in patients with herpes infection (Tatnall et al, 1995), administration of the drug after development of target lesions is of no benefit (Huff, 1988). The natural history of EM minor is spontaneous resolution after several weeks without sequelae (Schofield et al, 1993), although recurrences are common (Huff and Weston, 1989). Oral antihistamines may provide symptomatic relief. For immunosuppressed patients, the time course of EM minor outbreaks may be longer, and the frequency of recurrence may be greater (Schofield et al, 1993).

The major form of EM has been called Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) in the past, although there remains some controversy as to whether EM major and SJS are distinct entities (Bachot and Roujeau, 2003; Williams and Conklin, 2005). SJS is a much more serious illness than EM minor with features similar to extensive skin burns (Parrillo, 2007). In its more severe forms, SJS may mimic life-threatening toxic epidermal necrolysis. Admission to the intensive care unit or burn unit may significantly reduce morbidity and mortality in this condition (Wolf et al, 2005). Most patients with SJS have a prodromal upper respiratory illness (fever, cough, rhinitis, sore throat, and headache) that progresses after 1 to 14 days to the abrupt development of red macules with blister formation and areas of epidermal necrosis. Genital involvement includes erythema and erosions of the labia (Fig. 15–6), penis, and perianal region.

Figure 15–6 Labial erosions in a case of Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

(From Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2003. p. 319.)

A vast array of inciting factors has been implicated in the development of SJS, with drug exposures being the most commonly identified. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents are the most frequent offending agents followed by sulfonamides, tetracycline, penicillin, doxycycline, and anticonvulsants (Chan et al, 1990). In contrast to EM minor, there is rarely an association with an infectious agent (Weston, 2003). SJS generally has a protracted course of 4 to 6 weeks and may have a mortality rate approaching 30%. Severe scarring of denuded skin may result in a range of complications including joint contractures, vaginal stenosis, urethral meatal stenosis, and anal strictures (Brice et al, 1990; Weston, 2003). Treatment involves immediate removal of the offending drug and supportive care similar to the management of severe burns. There is currently no strong evidence for any specific therapy for SJS (Weston, 2003), and the role of systemic corticosteroids in treating SJS remains controversial (Rasmussen, 1976; Tripathi et al, 2000; Weston, 2003).

Papulosquamous Disorders

Papulosquamous disorders are a disparate group of diseases that share a common primary lesion: scaly papules and plaques (Table 15–4).

Table 15–4 Differential Diagnosis of Papulosquamous Lesions

From Margolis DJ. Cutaneous disease of the male external genitalia. In: Walsh PC, editor. Campbell’s urology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a common disease affecting up to 2% of the population (Christophers, 2001; Nestle et al, 2009). For patients with a predisposition, which is likely polygenic in nature, triggering factors such as trauma, infection, psychological stress, or new medications can elicit a flare up in the psoriatic phenotype. One third of affected patients have a family history of psoriasis (Melski and Stern, 1981; Hensler and Christophers, 1985; Margolis, 2002).

The characteristic lesion is a sharply demarcated erythematous plaque with silvery-white scales (van de Kerkhof, 2003). Its pattern can be limited to the elbows or knees, or distributed over the entire surface of the skin. Although psoriasis can appear at any age, two peaks of onset have been identified: 20 to 30 and 50 to 60 years of age. Patients complain of a significant impairment in their quality of life due to pruritus and the cosmetic impact of these visible plaques.

Psoriatic involvement of the genitalia is relatively common, although usually within the context of a generalized cutaneous disorder. Patients may present with concerns for malignancy or sexually transmitted infection when psoriatic lesions are present on the genitals. The presence of characteristic lesions on the elbows, knees, buttocks, nails, scalp, and umbilicus may help direct the diagnosis (Fig. 15–7A) (Margolis, 2002). When lesions are present in the inguinal folds and intergluteal cleft, scaling may be absent (so-called “inverse psoriasis”) (Goldman, 2000). When evaluating nonscaling erythematous plaques in the inguinal folds, the diagnosis of fungal involvement (i.e., tinea or Candida) should be considered. In circumcised men, psoriatic plaques are often present on the glans and corona, whereas in uncircumcised men, lesions are commonly hidden under the preputial skin (Buechner, 2002). In some cases, however, psoriasis involves the entire penis and scrotum (Fig. 15–8).

(A, From Callen JP, Greer DE, Hood AF, Paller AS. Color atlas of dermatology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1993. p. 320; B, from Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. Edinburgh: WB Saunders; 2009. p. 152.)

Figure 15–8 Psoriasis involving the entire penis and scrotum.

(From Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2003. p. 130.)

Psoriasis is a chronic disease with a relapsing and remitting course. A variety of topical and systemic therapies have been developed and applied to this difficult problem. However, despite these therapies, as many as 40% of psoriasis sufferers express frustration with the ineffectiveness of current treatments (Krueger et al, 2001). For genital psoriasis, the mainstay of therapy is the use of low-potency topical corticosteroid creams for short courses. Examples include a preparation of 3% liquor carbonis detergens in 1% hydrocortisone cream (Fisher and Margesson, 1998). These preparations should not be used continuously for more than 2 weeks on thin genital skin or in areas occluded by skin folds (Margolis, 2002). Other topical therapies for psoriasis include vitamin D3 analogues, dithranol, and retinoids, although these agents may be too irritating for genital skin application. Photochemotherapy combining an ingested psoralen with ultraviolet radiation (PUVA) has been used extensively to treat psoriasis (Stern, 2007). However, a dose-dependent increase in the risk of genital squamous cell carcinoma has been associated with high-dose PUVA therapy for psoriasis elsewhere on the body (Stern, 1990; Stern et al, 2002). Genital shielding during PUVA therapy is strongly recommended; therefore this modality is contraindicated for treating psoriatic lesions localized to genital skin. For patients with extensive psoriasis, systemic therapy with methotrexate, cyclosporine, or retinoids may be appropriate. Experimental therapies that have shown promise in treating psoriasis include the 308-nm excimer laser (Gerber et al, 2003), vitamin D receptor ligands (Bos and Spuls, 2008), and antibodies or antisense oligonucleotides against T-lymphocyte surface molecules (Gottlieb et al, 2000a, 2000b), tumor necrosis factor (Chaudhari et al, 2001; Bos and Spuls, 2008), or intracellular adhesion molecules (Gottlieb et al, 2000a, 2000b).

Reiter Syndrome

This is a syndrome composed of urethritis, arthritis, ocular findings, oral ulcers, and skin lesions. The skin findings, particularly when present on the genitalia, may be mistaken for psoriatic lesions (Fig. 15–9). Reiter syndrome is more common in men than in women and is rarely diagnosed in children. It is generally preceded by an episode of either urethritis (Chlamydia, Gonococcus) or gastrointestinal infection (Yersinia, Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Neisseria, or Ureaplasma species) and is more common in HIV-positive patients (Rahman et al, 1992; Margolis, 2002; Wu and Schwartz, 2008). There is a strong genetic association with the HLA-B27 haplotype. Whether cross reactivity between bacterial antigens and HLA-B27 leads to autoimmunity in Reiter syndrome remains controversial (Ringrose, 1999; Yu and Kuipers, 2003).

(From Habif TP. Clinical dermatology. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2004. p. 217.)

Conjunctivitis is the most common ocular manifestation, although iritis, uveitis, glaucoma, and keratitis may occur. Polyarthritis and sacroiliitis are the most common orthopedic complaints and may lead to chronic disability in a small minority of cases (van de Kerkhof, 2003). Psoriasiform skin lesions present on the penis are referred to as balanitis circinata (Fig. 15–10). These lesions may be difficult to differentiate from psoriasis, and histologic analysis of biopsy specimens cannot consistently differentiate the two conditions (Margolis, 2002). The course of Reiter syndrome involving the genitalia is usually self-limited, lasting a few weeks to months. Lesions may respond to topical corticosteroids, and systemic therapy is rarely required.

(From Callen JP, Greer DE, Hood AF, Paller AS. Color atlas of dermatology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1993. p. 160.)

Lichen Planus

Lichen planus (LP), the prototype of the lichenoid dermatoses, is an idiopathic inflammatory disease of the skin and mucous membranes. The characteristic “lichenoid tissue reaction” is characterized by epidermal basal cell damage that is associated with a massive infiltration of mononuclear cells in the papillary dermis (Shiohara and Kano, 2003). Cutaneous LP may affect up to 1% of the adult population (Boyd and Neldner, 1991), and oral lesions may be present in as many as 4% (Scully et al, 1998). The pathogenesis of LP appears to be related to an autoimmune reaction against basal keratinocytes that express altered self-antigens on their surfaces (Morhenn, 1986).

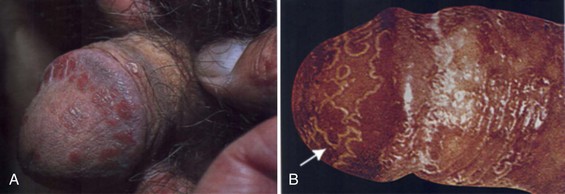

The primary lesion of LP is a small, polygonal-shaped, violaceous, flat-topped papule. These lesions may be widely separated or coalesce into larger plaques, which may ulcerate, particularly on mucosal surfaces. LP commonly involves the flexor surfaces of the extremities, the trunk, the lumbosacral area, the oral mucosa, and the glans penis (Margolis, 2002). On the genitalia, the clinical presentation of LP can be quite variable and includes isolated or grouped papules, a white reticular pattern, or an annular (ringlike) arrangement with or without ulceration (Fig. 15–11). In some cases, the lesions appear to form linear patterns related to skin trauma (the so-called Koebner phenomenon; also seen with psoriasis). The differential diagnosis of LP includes squamous cell carcinoma, Bowen disease, Zoon balanitis, psoriasis, secondary syphilis, and lupus erythematosus, and biopsy may be necessary to establish the diagnosis, particularly when the lesions are ulcerated (Shiohara and Kano, 2003). Lichenoid reactions can also occur in response to ingested drugs and contact allergens, and a careful search for potential offending agents is appropriate.

(A, From Korting GW: Practical dermatology of the genital region. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1981. p. 29; B to D, from du Vivier A: Atlas of clinical dermatology. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2002. p. 100); E, from Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. Edinburgh: WB Saunders; 2009. p. 137.)

The natural history of LP is benign, and the spontaneous resolution of cutaneous lesions has been observed in up to two thirds of cases after one year (Shiohara and Kano, 2003), although the oral form may persist significantly longer (Mignogna et al, 2000). Although bothersome pruritus is common with LP, asymptomatic lesions on the genitalia do not require treatment. The primary modality of treatment for symptomatic cutaneous LP is topical corticosteroids, with the caveats mentioned previously about their use on genital skin. There also appears to be a role for topical calcineurin inhibitors in the management of LP (Luger and Paul, 2007). For severe cases, systemic corticosteroids (15 to 20 mg per day; 2- to 6-week course [Boyd and Neldner, 1991]) have been shown to shorten the clearance time of LP lesions from 29 to 18 weeks (Cribier et al, 1998). Other systemic therapies for severe LP include cyclosporine, tacrolimus, griseofulvin, metronidazole, and acitretin (Ho et al, 1990; Boyd and Neldner, 1991; Cribier et al, 1998; Buyuk and Kavala, 2000; Madan and Griffiths, 2007), although randomized trials demonstrating efficacy are generally lacking.

Lichen Nitidus

Lichen nitidus (LN) is an unusual inflammatory eruption characterized by tiny, discrete, flesh-colored papules arranged in large clusters. Although there is some debate whether LN may represent a variant of LP (Aram, 1988), the two entities are histologically distinct. LN has a dense, well-circumscribed, lymphohistiocytic infiltrate closely apposed to the epidermis (Shiohara and Kano, 2003). Commonly involved sites include the flexor aspects of the upper extremities, the genitals, trunk, and dorsal aspects of the hands. Nail involvement is common. Similar to LP, the natural history of LN is one of spontaneous resolution, with the majority of patients (69%) manifesting disease for less than one year (Lapins et al, 1978). Patients should be reassured that these genital lesions are not infectious and should resolve with time. For symptomatic pruritus, genital lesions usually respond to topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines (Shiohara and Kano, 2003).

Lichen Sclerosus

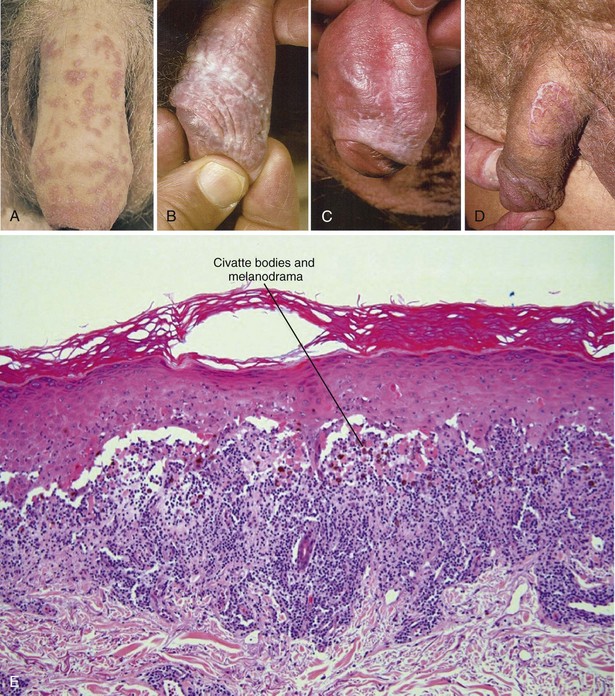

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS) is a chronic inflammatory disease with a predilection for the external genitalia. LS is 6 to 10 times more prevalent in women than in men, generally presenting around the time of menopause (Wojnarowska and Cooper, 2003). For patients with genital LS, 15% to 20% have extragenital disease (Powell and Wojnarowska, 1999). LS is a scarring disorder characterized by tissue pallor, loss of architecture, and hyperkeratosis (Fig. 15–12). It tends to affect older men (>60 years of age) (Ledwig and Weigand, 1989) and can be associated with pain during voiding or erection (Margolis, 2002). The glans penis and foreskin are usually affected, and the perianal involvement common in women is usually absent. Preputial scarring from LS can lead to phimosis, and circumcision is usually curative, although recurrence in the circumcision scar may occur. The late stage of this disease is called balanitis xerotica obliterans, which can involve the penile urethra and result in troublesome urethral stricture disease.

(A, From Callen JP, Greer DE, Hood AF, Paller AS: Color atlas of dermatology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1993. p. 327; B, from du Vivier A. Atlas of clinical dermatology. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2002. p. 716; C, from Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2003. p. 1101.)

Despite the similarities in name, LS shares little in common with LP and LN other than pruritus and a predilection for the genital region. Another critical distinction is that LS has been associated with squamous cell carcinoma of the penis, particularly those variants not associated with human papillomavirus, and may represent a premalignant condition (Velazquez and Cubilla, 2003; Bleeker et al, 2009). LS has specific histologic features, including basal cell vacuolation, epidermal atrophy, dermal edema, collagen homogenization, and focal perivascular infiltrate of the papillary dermis, and plugging of the ostia of follicular and eccrine structures (Margolis, 2002). Biopsy is worthwhile both to confirm the diagnosis and exclude malignant change (Powell and Wojnarowska, 1999).

From a management standpoint, long-term follow-up of patients with LS is important due to the association with squamous cell carcinoma. The application of potent topical steroids (such as clobetasol propionate 0.05%) for long courses (3 months) is well established as a treatment for LS in women and may both improve symptoms and reverse the disease process (Dalziel et al, 1991) This regimen is contrary to the usual policy of avoiding long courses of steroid application to genital skin. The efficacy of similar approaches has not been confirmed in adult men, although benefits have been demonstrated in the pediatric age group (Kiss et al, 2001). A recent European, multicenter, phase II trial also supported the safety and efficacy of topical tacrolimus in the treatment of long standing LS (Hengge et al, 2006).

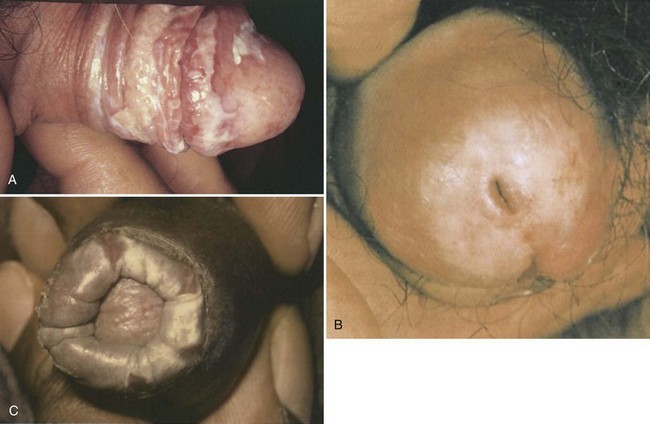

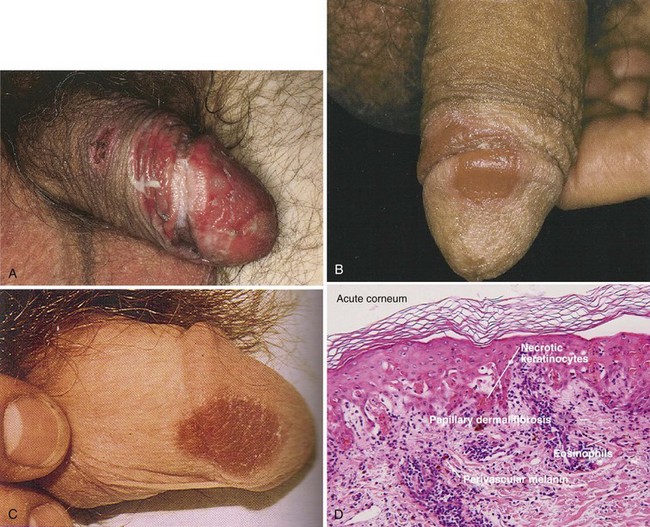

Fixed Drug Eruption

A fixed drug eruption occurs in response to oral medications, usually 1 to 2 weeks after the first exposure, and commonly involves the lips, face, hands, feet, and genitalia (Fig. 15–13). After subsequent re-exposure to the drug, the reaction presents in the exact same location, usually within 24 hours (hence the term “fixed”). The most common medications causing this reaction are sulfonamides, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, barbiturates, tetracyclines, carbamazepine, phenolphthalein, salicylates, oral contraceptives, and salicylates (Kauppinen and Stubb, 1985; Stubb et al, 1989; Thankappan and Zachariah, 1991).

(A, From Callen JP, Greer DE, Hood AF, Paller AS. Color atlas of dermatology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1993. p. 160; B, from Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2003. p. 345; C, from Habif TP: Clinical dermatology. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2004. p. 492; D, from Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. Edinburgh: WB Saunders; 2009. p. 149.)

When present on the penile shaft or glans, these lesions are usually solitary inflammatory plaques, which may be erosive and painful (Margolis, 2002). On the genitalia, the differential diagnosis includes herpes simplex infection or an insect bite. Removing the offending agent usually results in resolution of the lesion, although postinflammatory brown pigmentation may remain.

Seborrheic Dermatitis

This is a common skin disease characterized by the presence of sharply demarcated pink-yellow to red-brown plaques with a flaky scale. It shares a variety of features in common with eczematous dermatitis and could easily be grouped in that category. Common dandruff is a mild form of seborrheic dermatitis (SD) localized to the scalp. It has a predilection for areas rich in sebaceous glands and is generally present only during the first few months of life or post-puberty, when sebaceous glands are active. Common areas affected include the scalp, eyebrows, nasolabial folds, ears, and chest although the anus, penis, and pubic areas may also be involved (Margolis, 2002). Circumcision may be somewhat protective against the development of SD. In one study of 357 patients, the risk of developing penile SD was 2.5 times greater in the uncircumcised state (Mallon et al, 2000).

Adult SD has a chronic relapsing course (Webster, 1991). This condition is particularly common in patients with Parkinson disease, and up to 83% of AIDS patients may manifest SD (Froschl et al, 1990; Gupta and Bluhm, 2004). SD may involve a significant proportion of the body surface area, particularly in immunosuppressed individuals. Extensive and/or severe SD should raise concerns for possible underlying HIV infection (Fritsch and Reider, 2003). SD may be pruritic, and differentiation from psoriasis may occasionally be problematic. Unlike psoriasis, however, SD rarely involves the nails and tends to have a thinner associated scale.

Controversy concerning the etiology of SD revolves around a possible autoimmune response to a component of normal skin flora, the yeast Malassezia furfur (Pityrosporum ovale). Although M. furfur can be isolated from the lesions of SD, the number of organisms is only about twice that observed in normal control skin (Nenoff et al, 2001). Likewise, severely SD-affected HIV patients do not harbor more organisms than HIV patients without manifestations of SD (Pechere et al, 1999). Another factor potentially linked to SD is an elevated level of triglycerides and cholesterol at the skin surface (Fritsch and Reider, 2003).

Creams containing topical antifungals (i.e., ketoconazole) are the mainstay of SD treatment on the body and have a 75% to 90% response rate (Faergemann, 2000; Fritsch and Reider, 2003). For hair-bearing areas, “antidandruff” shampoos containing zinc, salicylic acid, selenium sulfide, tar, ciclopirox olamine, or ketoconazole are effective (Margolis, 2002; Squire and Goode, 2002). Because of the relapsing nature of SD, treatment often must be repetitive. Low-potency topical corticosteroids may play a role during the initial treatment of severe cases but should not be the primary mode of treatment for this chronic condition due to local steroid side effects.

Vesicobullous Disorders

Vesicobullous disorders are uncommon conditions often characterized by autoimmune damage to the epidermis or basement membrane (Table 15–5). On the genitalia, the rupture of blisters and bullae may leave behind erosions (Margolis, 2002).

Table 15–5 Differential Diagnosis of Vesicobullous Disorders

From Margolis DJ. Cutaneous disease of the male external genitalia. In: Walsh PC, editor. Campbell’s urology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002.

Pemphigus Vulgaris

Pemphigus is a family of autoimmune blistering diseases characterized by intraepidermal blisters due to the loss of keratinocyte cell–cell adhesion (Martel and Joly, 2001). These blisters are located in the deep epidermis close to the basal cell layer. The proposed immunopathology includes the development of autoantibodies directed against keratinocyte cell surface markers and desmosomes (Amagai et al, 1996; Zhou et al, 1997; Joly et al, 2000).

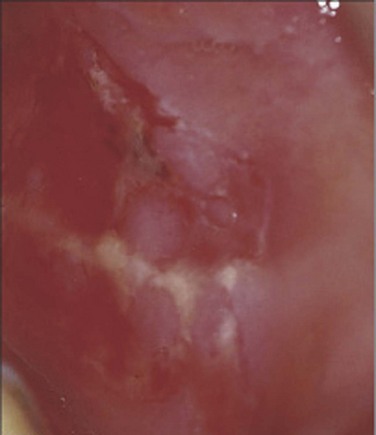

Almost all pemphigus patients will have painful oral mucosal erosions, and over half will have cutaneous blisters that may involve the genitalia. Characteristic oral lesions are, therefore, an important clue to the diagnosis (Fig. 15–14). The cutaneous blisters are thin-walled and easily broken, leaving behind a painful erosion. The loss of epidermal cohesion seen in pemphigus leads to the characteristic Asboe-Hansen sign: spreading of fluid under the adjacent normal-appearing skin away from the direction of pressure on the blister (Amagai, 2003). In severe cases, without appropriate treatment, pemphigus may be fatal due to the loss of the epidermal barrier function of large areas of affected skin. Treatment for pemphigus usually depends on systemic corticosteroids, although minimization of steroid dose is an important goal to limit side effects. The addition of immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine and cyclophosphamide may be beneficial due to their corticosteroid-sparing effect (Amagai, 2003).

Figure 15–14 Characteristic painful oral mucosal erosions in pemphigus vulgaris.

(From Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2003. p. 455.)

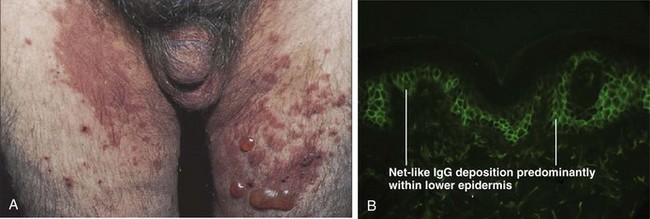

Bullous Pemphigoid

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is a subepidermal blistering disease that is more common in men and generally afflicts patients older than 60 years of age (Rzany and Weller, 2001). There is enrichment for specific HLA class II alleles in BP patients as compared with normal controls (Delgado et al, 1996), supporting an autoimmune mechanism of pathogenesis. In BP, autoantibodies against specific proteins involved in cell–cell adhesion (BP180, BP230) are present. These proteins are components of hemidesmosomes, structures that mediate epidermal–stromal adhesion. Binding of autoantibodies to these structures leads to complement activation and a cascade of events resulting in tissue damage, epidermal–dermal separation and blister formation (Kitajima et al, 1994; Lin et al, 1997).

Clinically, the presentation of BP can be highly variable. It generally begins with a non-bullous phase characterized by severe itching and nonspecific skin findings. As the disease progresses to the bullous phase, vesicles and blisters appear on normal skin or areas containing confluent erythematous plaques. The blisters are tense, tend to form on flexor surfaces, and may involve the inner thighs and genitalia (Fig. 15–15A). Mucous membranes may also be involved, although less commonly than in pemphigus. The diagnosis is made by a combination of clinical, histologic, and, often most importantly, immunohistochemical features such as the deposition of IgG antibodies along the basement membrane (Fig. 15–15B) (De Jong et al, 1996). Treatment of BP is similar to that described for pemphigus, with systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressants playing primary roles (Kirtschig and Khumalo, 2004). For treatment-resistant cases, intravenous immunoglobulin or plasmapheresis may be beneficial (Hatano et al, 2003; Lee et al, 2003; Ruetter and Luger, 2004; Wetter et al, 2005).

(A, From Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2003. p. 465; B, from Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. Edinburgh: WB Saunders; 2009. p. 169.)

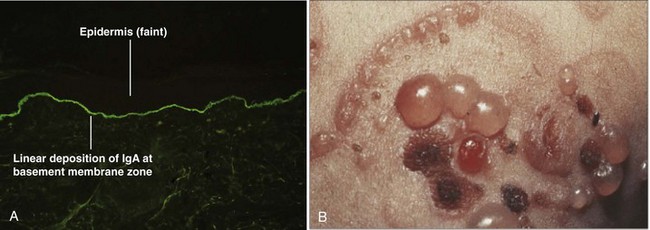

Dermatitis Herpetiformis and Linear IgA Bullous Dermatosis

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) is a cutaneous manifestation of celiac disease and is generally associated with gluten sensitivity (Karpati, 2004). It is most commonly found in people of Northern European origin. There is a close association of DH with certain HLA class II DQ2 alleles (DQA1*0501, DQB1*02) (Reunala, 1998). Pruritic plaques, papules, and vesicles in a symmetrical distribution characterize DH. These vesicles may form “herpetiform” groups on an erythematous base. Patients may also complain of pain and burning over the lesions. Diagnosis can be confirmed by biopsy and direct immunofluorescence, which shows a granular pattern of IgA deposition at the basement membrane. Treatment includes the use of dapsone and a strict gluten-restricted diet (Frodin et al, 1981; Andersson and Mobacken, 1992).

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD), in contrast, is not associated with celiac disease. As the name implies, a linear pattern of antibody deposition at the basement membrane is found on immunohistochemistry testing in LABD (Fig. 15–16). Characteristic clinical features include vesicles and bullae arranged in a combination of circumferential and linear orientations. Treatment with either sulfapyridine or dapsone is usually effective in controlling LABD, and long-term spontaneous remission rates of 30% to 60% have been described (Wojnarowska et al, 1988).

(A, From Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. Edinburgh: WB Saunders; 2009. p. 170; B, from Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2003. p. 485.)

Hailey-Hailey Disease

Hailey-Hailey disease (HH) is an autosomal-dominant blistering dermatosis that usually develops within the second or third decade of life (Burge, 1992). It has a predilection for the intertriginous areas, including the groin and perianal region (Fig. 15–17). In women, disease in the inframammary folds is common, although vulvar disease is unusual (Wieselthier and Pincus, 1993). Symptoms include an unfortunate combination of pruritus, pain, and a foul odor. As heat and sweat exacerbate the condition, HH tends to worsen during the summer months (Burge, 1992). Skin findings include confluent areas of vesicles and fragile blisters, which form due to aberrant keratinocyte cell adhesion. Lesions may be confined to the axilla or groin, and superinfection with yeast or bacteria may compound the problem. Histologic examination may be helpful in differentiating HH from impetigo, pemphigus, intertrigo, and Darier disease (Margolis, 2002). Treatment includes wearing lightweight, breathable clothing to avoid friction and sweating. Lesions may respond to topical or intralesional corticosteroids, with the caveats mentioned previously about the use of these agents on intertriginous skin. For disease resistant to medical therapy, wide excision and skin grafting have been effective, as have local ablative techniques such as dermabrasion and laser vaporization (Hamm et al, 1994; Christian and Moy, 1999; Hohl et al, 2003).

(A, From du Vivier A. Atlas of clinical dermatology. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2002. p. 688; B, from Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2003. p. 830.)