CURRENT OUTCOME DATABASES

United States Renal Data System

In 1988, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) awarded a contract for formation of a national end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) registry. This resulted in the formation of the United States Renal Data System (USRDS) (2). When an incident patient begins dialysis treatment in the United States, a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) 2728 Medical Evidence Report is completed and submitted to the appropriate End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Network (see following text). A similar process occurs when a dialysis patient dies with CMS 2746 ESRD Death Notification Form. This data is then blindly combined with other CMS data such as Medicare part A, B and D claims from care of dialysis patients.

An annual report based on this data is published and readily available online in many formats. Researchers with expertise can purchase the database and separately analyze the data for their own academic purposes.

The accuracy and integrity of the USRDS data, while widely assumed, has only been examined cursorily. Two studies in 1992 demonstrated a >90% accuracy of most data points obtained from patients (3,4). However, other studies raise concerns. In one study on erythropoiesis-stimulating agent (ESA) use in 8,033 patients at the Department of Veteran Affairs, the sensitivity of accuracy for predialysis ESA use recorded on the 2728 form was 57% (5). Another study of 1,105 incident dialysis patients showed a sensitivity of 0.59 in reporting the 17 comorbid conditions on the 2728 form with significant underreporting (6). Finally, the inaccuracy of the Death Notification Form was demonstrated during the Hemodialysis (HEMO) trial where the major source of misclassification was the frequent use of “unknown cause of death” and “other heart conditions” on the Death Notification Form (7).

Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study

The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) is an international, prospective, observational study beginning in 1996 and divided in multiple time periods (“phases”) that examines multiple patient outcomes (8). Over 200,000 patient-years patients in over 600 hemodialysis centers have been included in the data analysis in the first five phases, and the annual reports are available in a variety of formats and online. In 2013, peritoneal dialysis collection began for Peritoneal Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (PDOPPS) (9).

Large Dialysis Organizations

In the United States, over 60% of patients undergo dialysis therapy in outpatient facilities owned and operated by one of two large corporations. With the introduction of computers and large-scale database management software, hundreds of millions of data points can be analyzed regarding ESKD (10). These databases can be used to measure various clinical outcomes and suggesting where and how clinical attention may be needed (11–13).

The recruitment of the Large Dialysis Organization (LDOs) to perform structured, nonclassically randomized trials, so-called “large pragmatic trials” may help answer clinical questions in a more timely and less costly manner than the current NIDDK process. The first of these trials in dialysis will examine the effect of 4.25 hours of hemodialysis versus usual care in incident hemodialysis patients (14,15).

GOVERNMENT MEASURES

GOVERNMENT MEASURES

End-Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program

In 2008, the United States Congress passed the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act, which directed the Secretary of Health and Human Services to establish quality incentives for providers of dialysis (1). The incentive chosen was avoidance of a payment reduction from CMS of up to 2%.

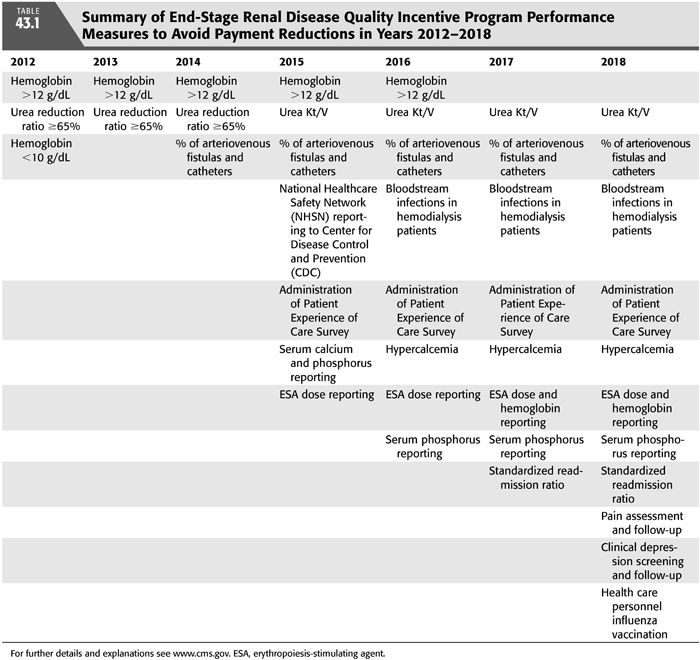

New quality targets are chosen each year according to a deliberate process with some public input (TABLE 43.1). Although the inclusion of quality measurements, better patient care, and safety and implementation of best clinical practices has been widely praised, the particular choices of quality measures have been controversial. From a global perspective of caring for a complex patient, intense concentration on a few specific measures may distract from other important functions of the dialysis center and clinician. Second, some of the measures chosen have questionable scientific rationale and could potentially harm patients or at best have no effect if implemented aggressively. For example, in 2012, avoiding a hemoglobin less than 10 g/dL has no basis in literature, and earlier studies demonstrated that the use of ESA may have harmful side effects (16). Furthermore, urea reduction ratio (URR) as an absolute measure of dialysis adequacy had been abandoned by most practitioners by 2012 because of its lack of considering ultrafiltration, dialysis time, residual kidney function, and the other 12 dialysis treatments during the month in addition to marginal evidence that small solute clearance alone corrects the uremic syndrome. To put it bluntly, ESKD patients were not suffering and dying in 2012 for lack of hemoglobin values between 10 and 12 g/dL and a URR ≤65%.

Dialysis Facility Compare

Utilizing electronic data derived from Medicare claims and electronic data submitted directly from dialysis centers (Consolidated Renal Operations in a Web-enabled Network or CROWNWeb), CMS annually gives each dialysis facility a “star rating” from 1 to 5 based on the attainment of certain measurable outcomes. These ratings are posted online and also required to be visible in each dialysis center.

While trying to attain the laudable goal of providing dialysis patients a system to judge their care similar to the way they would choose a restaurant or buy a pair of shoes, the current methodology has raised concerns. First, the system does not measure attained outcomes but rather separates each variable along a curve. Thus, there will always be 10% of dialysis centers with a 1-star rating and 10% of facilities with a 5-star rating regardless of the actual metrics obtained. Second, as providers aggressively react to the few metrics, the separation between a 1-star rating and a 5-star rating may be clinically insignificant. For example, the difference in Kt/V values and hypercalcemia percentages are a few percentage points in the high 90s. Lastly, some physicians may overreact to the metrics with unintended consequences.

End-Stage Renal Disease Networks

In 1978, the United States Congress authorized the establishment of ESRD Network Organizations to support the ESKD program. Currently as of 2015, there are 18 networks with contracts awarded by CMS. The ESRD Network Organization is responsible in its geography for collecting data for the ESKD program, improving the quality of care, addressing patient grievances, and providing technical support to patients, dialysis providers, and other health care professionals and organizations involved in the care of ESKD patients. However, even the well-intentioned programs of the ESRD Networks can go awry such as the Fistula First Initiative which had some unintended consequences of patients likely having catheters in place longer while waiting for multiple fistula surgeries and maturation (17,18).

Randomized Controlled Trials in Dialysis

Given the multiple clinical issues in patients with kidney failure requiring dialysis therapies, the field would seem a frequent target of innovative clinical studies. Alas, this has not been the case and, furthermore, patients on dialysis or even with moderate chronic kidney disease are often excluded from other trials with diverse disease states.

Additionally, many of the interventions suggested by numerous observational studies in ESKD patients have been shown to not be effective when rigorously and formally tested. Applying conclusions broadly from nonrandomized trials has led to errors in clinical practice. One prominent example of this was the Canada-USA (CANUSA) study in peritoneal dialysis where the failure to account for the impact of residual renal function over time led to recommendations of targeting of Kt/V urea >2.1 in thousands of patients who were previously doing fine and potentially led to more glucose exposure and an early technique failure (19,20).

Despite the lack of many ongoing or planned clinical trials to improve care to the ESKD patient, there is a recognition of the continued scope of the problem. In 2012, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced an innovation challenge with ESKD and received 32 proposals from which 3 were selected including a vascular access device, an implantable artificial kidney, and a wearable artificial kidney (21).

Clinical Guidelines

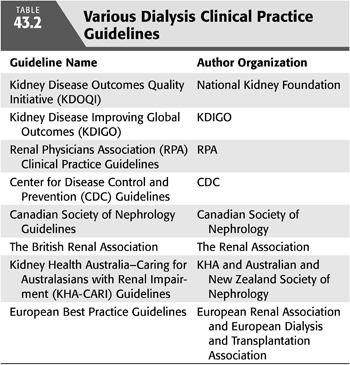

The combination of outcome measurement and expert opinion has led to the formation of various guidelines for managing ESKD patients (TABLE 43.2). While these well-meaning endeavors can lead to a standardization of therapy and particularly attention on substandard performance, unintended consequences can potentially lead to worse outcomes. One of the better known examples of this is the KDOQI anemia management guidelines (22).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree