Cooper Ligament Repair

Alex Nagle

Kenric Murayama

The Cooper ligament repair is a primary tissue repair that involves suturing the conjoined tendon (superiorly) to Cooper’s ligament (inferiorly) medial to the femoral vein and to the inguinal ligament at the level of and lateral to the femoral vein. It typically requires a relaxing incision and careful dissection near the femoral vessels. It provides closure of the femoral, indirect and direct spaces, and, as such, can be used to repair any hernia defect that may occur in the groin. However, it is almost always reserved for the repair of femoral hernias. Femoral hernias account for 2% to 4% of groin hernias, are more common in women, and are more apt to present with strangulation and require emergency surgery. The postoperative morbidity and mortality increase significantly in patients undergoing emergent repair. This highlights the importance of repairing femoral hernias in an elective setting and suggests that watchful waiting is not a prudent strategy in patients with femoral hernias, even those who are asymptomatic.

The Cooper ligament repair is rarely performed today, as it has been replaced by tension-free prosthetic mesh repairs. The well-known advantages of tension-free hernia repair have led to the development of various mesh techniques for femoral hernia repair. In addition, a laparoscopic approach provides an excellent repair of femoral hernias. However, there remain clinical situations in which a prosthetic mesh should be avoided and a Cooper ligament repair is indicated. The most common clinical scenario involves an emergent operation for a small bowel obstruction secondary to an incarcerated femoral hernia.

Femoral hernia repair when a prosthetic mesh is contraindicated

Femoral hernia repair in the presence of infected mesh

Femoral hernia repair in the presence of gangrenous bowel

Femoral hernia repair in the presence of a contaminated field

Complete medical history is essential. Any existing co-morbidities should be identified and addressed. Cardiac and pulmonary consultations are occasionally indicated. Accurate documentation of any previous abdominal, pelvic, vascular, or groin surgery.

Complete physical examination with focus on both groins including testicles. It is important to document the status of the testicles preoperatively.

In a patient with a small bowel obstruction secondary to an incarcerated femoral hernia, proper resuscitation is essential prior to going to surgery.

The risks and benefits of surgery versus expectant management, as well as potential surgical complications, should be reviewed with the patient. The risk of postoperative neuralgia should be discussed. All male patients are told of the possible occurrence of ischemic orchitis and subsequent testicular atrophy. In the setting of an incarcerated femoral hernia, the risk of bowel resection and possible laparotomy are discussed.

Peri-operative antibiotics: The role of routine antibiotic prophylaxis for elective inguinal hernia remains controversial. There is a body of literature indicating no statistically significant advantage to the use of antibiotic prophylaxis in the performance of routine inguinal hernia repair with or without the use of a prosthetic mesh. Nevertheless, many surgeons argue that antibiotic prophylaxis is both inexpensive and safe, and that such practice should not be considered inappropriate. In the acute setting of a small bowel obstruction secondary to an incarcerated femoral hernia, peri-operative antibiotic should be given within 30 minutes of the initial skin incision.

Decompression of the bladder immediately preoperatively. In most elective cases a foley catheter is not necessary.

DVT prophylaxis with calf-length pneumatic compression devices.

Anesthesia options for femoral hernia repair include general, spinal, or local with intravenous sedation. Emergent cases of small obstruction secondary to an incarcerated femoral hernia will require general anesthesia.

Anatomy

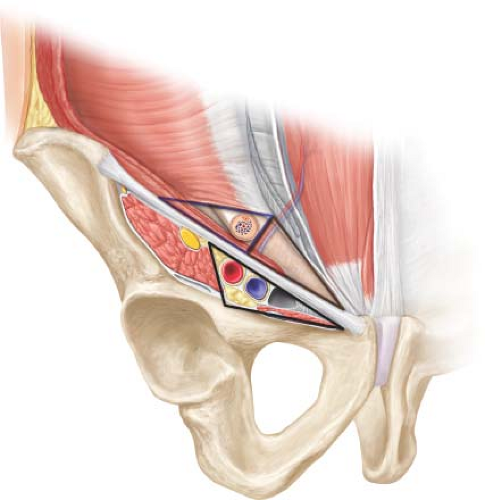

As with any hernia repair a thorough working knowledge and understanding of the anatomy of the inguinal region is mandatory. All groin hernias begin as a weak area within the myopectineal orifice. The myopectineal orifice is divided into the medial, lateral, and femoral triangles (Fig. 6.1). With a decreased strength of the aponeurotic

fibers in this area from defective collagen metabolism (e.g., from smoking) and a gradual attenuation from increased intraabdominal pressure (e.g., from prostatism, obesity, constipation, or chronic lung disease), a hernia can result. The transversalis fascia deteriorates and allows a peritoneal protrusion through it. Depending on the length of the insertion of the transversus abdominis on Cooper’s ligament, the presence of a patent processus vaginalis, and the width of the femoral ring, the hernia might be direct, indirect, femoral, or any combination of the three.

fibers in this area from defective collagen metabolism (e.g., from smoking) and a gradual attenuation from increased intraabdominal pressure (e.g., from prostatism, obesity, constipation, or chronic lung disease), a hernia can result. The transversalis fascia deteriorates and allows a peritoneal protrusion through it. Depending on the length of the insertion of the transversus abdominis on Cooper’s ligament, the presence of a patent processus vaginalis, and the width of the femoral ring, the hernia might be direct, indirect, femoral, or any combination of the three.

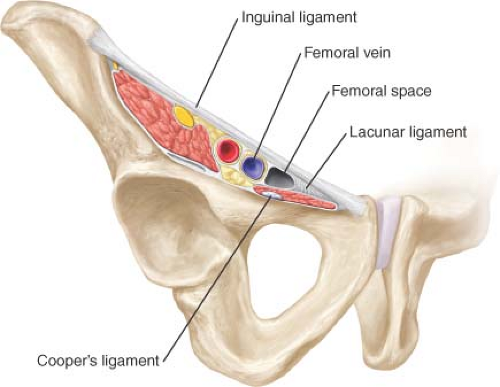

Figure 6.2 Borders of a femoral hernia. Anterior—inguinal ligament, posterior—Cooper’s ligament, medial—lacunar ligament, lateral—femoral vein. |

Borders of a femoral hernia (Fig. 6.2):

Anterior: Inguinal ligament

Posterior: Cooper’s ligament (pubic ramus)

Medial: Lacunar ligament

Lateral: Femoral vein

Technique

Skin preparation with clipping rather than shaving is preferred.

The surgical area is prepped and draped in a sterile fashion.

An oblique inguinal skin incision is utilized. Using electrocautery the soft tissue is dissected down to the level of the aponeurosis of the external oblique. Appropriate retractors are utilized.

The aponeurosis of the external oblique is dissected and the external ring is identified.

The aponeurosis of the external oblique is opened in the direction of its fibers extending through and obliterating the external ring.

The ilioinguinal nerve is identified and is usually preserved, but it may also be excised according to the surgeons’ preference.

The spermatic cord is mobilized in the canal but is not disturbed medial to the pubic tubercle to preserve testicular collateral circulation. At the level of the pubic tubercle, a penrose drain is placed around the cord structures and can be used to provide retraction allowing inspection of the inguinal floor (Fig. 6.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree