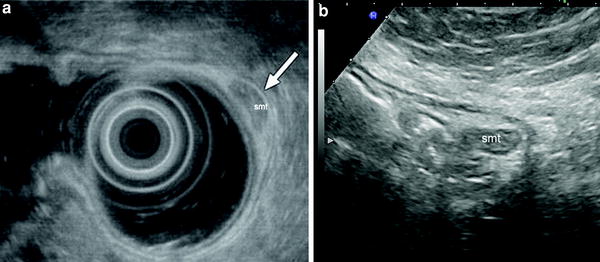

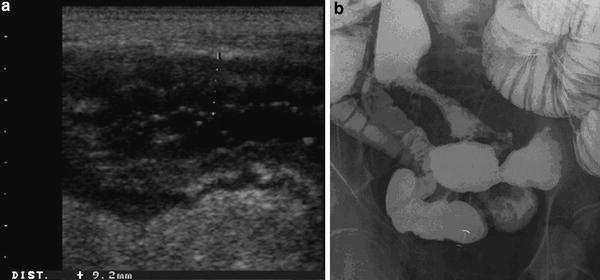

Fig. 1

Submucosal tumor (smt) of gastric antrum. Endosonography (a) and gastric hydrosonography (b) show a small submucosal lesion

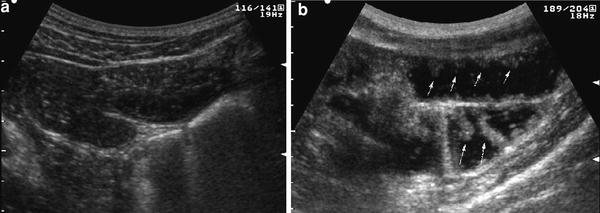

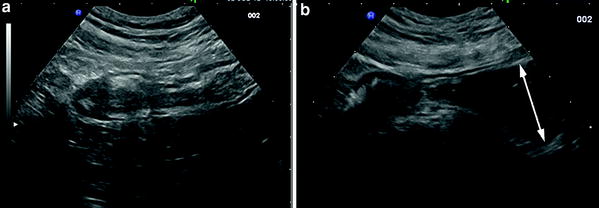

Fig. 2

Submucosal tumor (smt) of gastric antrum. Endosonography (a) and gastric hydrosonography (b) show a small submucosal lesion

However, when these investigations, for various reasons, cannot be performed, or in the case of surveillance of benign submucosal lesions previously assessed by EUS, hydrosonography of the stomach can be taken into consideration as an inexpensive, non-invasive and simple alternative. In particular, hydrosonography of the stomach can be considered a valid alternative to EUS for: (1) diagnosis (and follow-up) of extraluminal gastric compression, and (2) detection and surveillance of gastric submucosal tumours. In this regard, it has been shown that in gastric submucosal tumors can be visualized (and measured) using trans-abdominal ultrasound in 69–93 % of patients (Tsai et al. 2000; Futagami et al. 2001; Polkowski et al. 2002). In particular, Futagami et al. (2001) showed that the overall detection of the lesions was 82.5 %, but the detection rate varied according to the lesion size, being approximately 95 % for submucosal tumors over 20 mm in diameter, and 97 % for the lesions over 30 mm in diameter.

3 Small Intestine Contrast Ultrasonography

Like the stomach and duodenum, the sonographic visualization of the small bowel can be improved by filling the bowel with water or echo-poor liquids, either directly infused into the small bowel using a nasojejunal tube and a peristaltic pump (Folvik et al. 1999) or administered orally (Pallotta et al. 1999a).

In both cases, the liquid contrast medium should be non-absorbable and non-fermentable. Isotonic anechoic electrolyte solutions containing PEG, which are used for bowel cleansing prior to colonoscopy, are now considered the contrast media of choice. PEG solutions comprise various products with similar composition (e.g., polyethylene glycol 4000 or 3350 at a dose of 58–59 g, magnesium sulphate 7 g, sodium sulphate 2.8–5.7 g, sodium bicarbonate 1.7 g, sodium chloride 0.8–1.5 g, and potassium chloride 0.74 g) and osmolarity (280–290 mOsm/kg). The difference between PEG 4000 and PEG 3350 is the molecular weight (4000 and 3350, respectively).

The ingestion of a variable amount of PEG, usually between 250 and 500 ml, provides an adequate distension of the intestinal loops, removes gas making sequential visualization of the entire small bowel, from the duodenum to terminal ileum, easier and also allowing measurement of wall thickness and luminal diameter (Pallotta et al. 1999a, 1999b, 2000) (Table 1).

Table 1

Type and amount of PEG used in small bowel evaluation and duration of examination, defined as time taken to image terminal ileum, and side effects, reported by various authors in the literature

Author (ref) | Contrast medium | Amount of PEG (ml) Mean (Range) | Time to image terminal ileum (min) Mean (Range) | Inconclusive incomplete exam due to side effects (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Cittadini et al. 2001 | PEG 4000 | 500 | 31 (10–90) | 0 |

Pallotta et al. 2001 | PEG 4000 | 388 (200–670) | 37 (12–90) | 0 |

Parente et al. 2004 | PEG 3350 | 624 (500–800) | 31 (20–60) | 1 (1) |

Calabrese et al. 2005 | PEG 4000 | 375 (250–500) | 40 (35–90) | 0 |

Dell’Aquila et al. 2005 | PEG 4000 | n.r. (500–800) | n.r. (30–60) | 0 |

Pallotta et al. 2005 | PEG 4000 | 370 (200–500) | 39 (12–90) | 0 |

Castiglione et al. 2008 | PEG 3350 | 750 | > 30 | 3 (7) |

Chatu et al. 2012 | PEG 4000 | 1000 | 30 | 5 (3.5) |

Folvik et al. 1999 a | MW 3350 | 2000 | 40 (20–90) | n.r |

Nagi et al. 2006 a | n.r. | (1000–1500) | 34 (n.r.) | 0 |

Válek et al. 2007 a | HP 7000 | 2000 | n.r. | 0 |

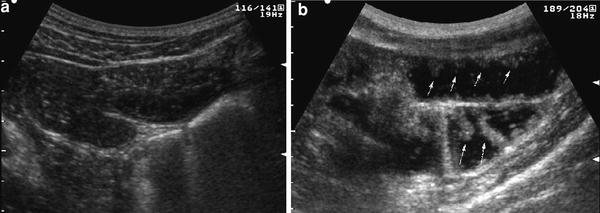

Sonographic assessment of the small bowel should be performed, after overnight fasting. After ingestion, the contrast solution passes from the stomach to the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum, distending the intestinal loops and thus improving the examination of the morphological and functional aspects of the bowel wall, such as thickening, echopattern, valvulae conniventes, and modality of contraction and relaxation (Fig. 3).

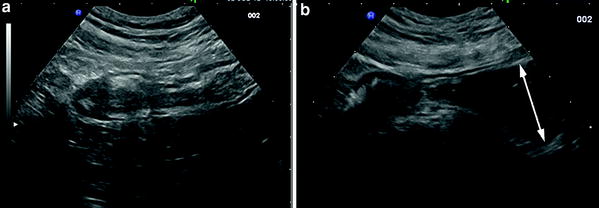

Fig. 3

Real-time ultrasonography of small bowel in basal fasting condition (a) and following administration of 500 ml of oral contrast agent (b). After contrast ingestion, entire small bowel is distended and visualized, and bowel wall and Kerckring’s folds may be well delineated

If distension and visualization of the entire bowel up to the terminal ileum is not adequate, further aliquots of PEG can be used. The amount of ingested US contrast agent does not significantly affect the luminal diameter or the wall thickness, at any level of the small bowel, in normal controls (Pallotta et al. 1999b).

Bowel examination can be performed immediately after ingestion of PEG or performed 10 min after PEG ingestion and then repeated at 10-minute intervals until the contrast can be seen to flow through the terminal ileum into the cecum. The mean duration of the entire examination is usually 30 min (Table 1). On account of the small amount of ingested contrast and palatability, the procedure is well-accepted and safe. None of the studies have reported significant side effects or major complaints during or immediately after PEG ingestion, apart from 2 studies, where five patients complained nausea and vomiting, which precluded the examination (Parente et al. 2004; Chatu et al. 2012). One study also reported minor and uneventful adverse events, such as nausea in 6.9 % and slight abdominal distension in 3.9 % of Crohn’s disease patients (Parente et al. 2004). In this regard, caution should be taken in using PEG in patients with confirmed or suspected small bowel occlusion. In these cases, as a safer oral contrast agent, variable amounts of tap water can be used.

Hydrosonographic assessment of the small bowel has been shown to be highly accurate in most studies, with sensitivity ranging between 63 and 100 % (median, 97.1 %) and specificity between 20 and 100 % (median, 97.2 %) depending on the underlying disease (Maconi et al. 2009). In fact, accuracy seems to be greater when patients with Crohn’s disease are well represented in the case series (Table 2).

Table 2

Results of comparative studies showing sensitivity and specificity of small bowel contrast ultrasonography (SICUS) or US enteroclysis (a) and conventional transabdominal ultrasonography (TUS) in detecting at least one small bowel lesion assessed by contrast radiology

Total | Patients with lesions | Patients with CD | Sensitivity | Specificity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Author | n. | n. (%) | n. (%) | TUS | SICUS | TUS | SICUS |

Folvik et al. 1999 a | 55 | 11 (20.0) | 17 (30.9) | n.e. | 7/11 (63.3) | n.e. | 44/44 (100) |

Pallotta et al. 1999a | 31 | 8 (25.8) | 5 (16.1) | n.e. | 8/8 (100) | n.e. | 22/23 (95.6) |

Cittadini et al. 2001 | 53 | 25 (47.2) | 16 (30.2) | n.e. | 18/25 (72.0) | n.e. | 28/28 (100) |

Pallotta et al. 2001 | 53 | 17 (32.1) | 8 (15.1) | n.e. | 17/17 (100) | n.e. | 35/36 (97.2) |

Parente et al. 2004 | 102 | 102 (100) | 102 (100) | n.r. (91.4) | n.r. (96.1) | n.e. | n.e. |

Calabrese et al. 2005 | 28 | 25 (89.3) | 25 (89.3) | 24/25 (96.0) | 25/25 (100) | n.e. | n.e. |

Pallotta et al. 2005 | 91 | 35 (38.5) | 16 (17.6) | 20/35 (57.1) | 33/35 (94.3) | 56/56 (100) | 55/56 (98.2) |

Pallotta et al. 2005 | 57 | 55 (96.5) | 55 (96.5) | 48/55 (87.3) | 54/55 (98.2) | n.e. | n.e. |

Biancone et al. 2007 | 22 | 21 (95.4) | 22 (100) | n.e. | 21/21 (100) | n.e. | 0/1 (0) |

Castiglione et al. 2008 | 40 | 22 (55.0) | 40 (100) | 17/22 (77.3) | 18/22 (81.8) | 17/18 (94.4) | 17/18 (94.4) |

Calabrese et al. 2009 | 72 | 67 (93.1) | 72 (100) | n.e. | 62/72 (92.5) | n.e. | 1/5 (20.0) |

Onali et al. 2010 | 25 | 24 (96.0) | 25(100) | n.e. | 25/25 (100) | n.e. | n.e. |

Chatu et al. 2012 | 143 | n.r. | 86 (60.1) | n.e. | n.r. (93.0) | n.e. | n.r. (99.0) |

Overall % | 772 | 412 | 392 (63.3) | 109/137 (79.6) | 288/316 (91.1) | 73/74 (98.6) | 202/211 (95.7) |

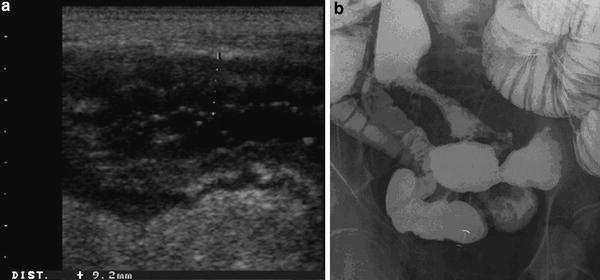

In fact, in these studies the diagnostic accuracy of small intestine contrast US was comparable to ileocolonoscopy, wireless capsule endoscopy, and small bowel X-ray in the assessment of number, site, extension, and post-operative recurrence of small bowel lesions (Pallotta et al. 2001, 2005; Parente et al. 2004; Onali et al. 2010; Calabrese et al. 2009; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4

Crohn’s disease lesions of small intestine well delineated by means of oral contrast ultrasound. The US oral contrast agent allows a more accurate evaluation of mucosal surface showing nodular and ulcerated appearance (a) comparable to that at contrast barium radiology (b), and providing information regarding thickening and transmural changes of ileal wall

When compared to conventional bowel US, the use of PEG slightly improved the overall sensitivity in the detection of small bowel lesions in Crohn’s disease patients (from 4 to 11 %; median, 4.85 %), also in the post-operative follow-up, but seemed to offer a greater advantage, compared to conventional bowel US, in detecting proximal small bowel lesions (sensitivity, 80 vs. 100 %, respectively) and in assessing the number and site of small bowel stenoses (Parente et al. 2004; Calabrese et al. 2005). As far as the detection of stenosis is concerned, small intestine contrast US may increase the sensitivity by 15–18 % vs trans-abdominal US in detecting patients with at least one stricture and by 22.2 % (sensitivity from 55.5 to 77.7 %) in detecting patients with at least two or more stenoses (Parente et al. 2004; Pallotta et al. 2012; Fig. 5). This advantage is presumably due to the fact that contrast agent, by favoring the assessment of dilatation of prestenotic jejunal/ileal loops, permits a better visualization of the narrowed segment or other causes of stenosis (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5

Crohn’s disease stricture of terminal ileum assessed by (a) conventional US (longitudinal section) and (b) US with oral contrast agent. In this patient, only the use of contrast agent (PEG 500 ml), allowed the assessment of the prestenotic dilatation (arrow)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree