Fig. 1

Barium enema showing diverticulosis of the sigmoid colon

Barium provides better mucosal detail than water-soluble contrast media. The possibility of perforation is a contraindication to its use, for fear of barium peritonitis. In these situations, water-soluble contrast should be used. Diverticulosis can be also diagnosed by endoscopy (Fig. 2); however, when diverticulitis is suspected clinically, endoscopy is contraindicated. After the acute phase of inflammation the colon should be examined to exclude a colon tumour. So a complete endoscopic colonic evaluation should generally be performed 6–8 weeks after the resolution of a diverticulitis. In case of inflammation, colonoscopy is often incomplete and painful for the patient. The risk for perforation is also higher because of the air insufflation.

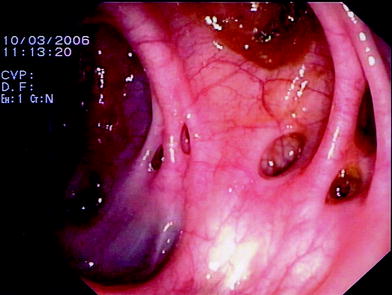

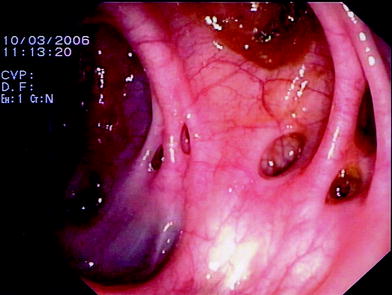

Fig. 2

Endoscopy shows diverticula

Sonography can also diagnose diverticulosis of the left hemicolon in many cases too (Hollerweger et al. 2002; Laméris et al. 2008; Valentino et al. 2009).

Normal diverticula present as hyperechoic protuberances of colonic wall with acoustic shadowing of variable intensity (Fig. 3).

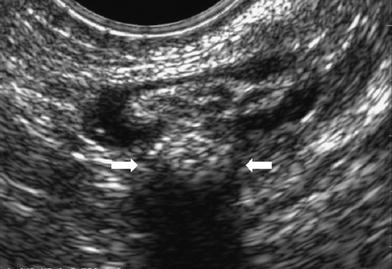

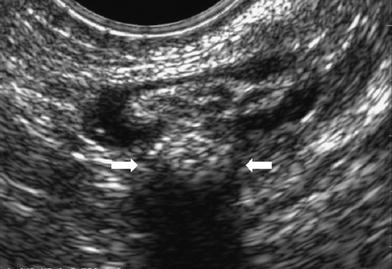

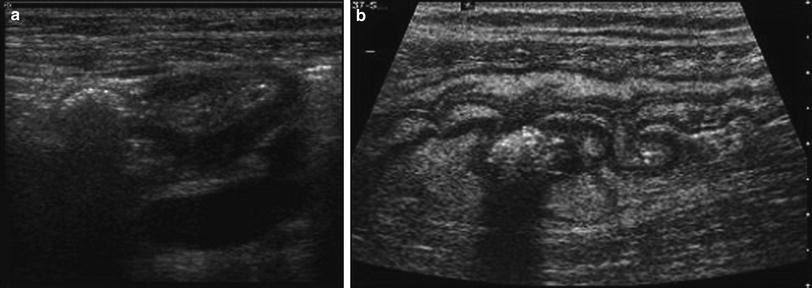

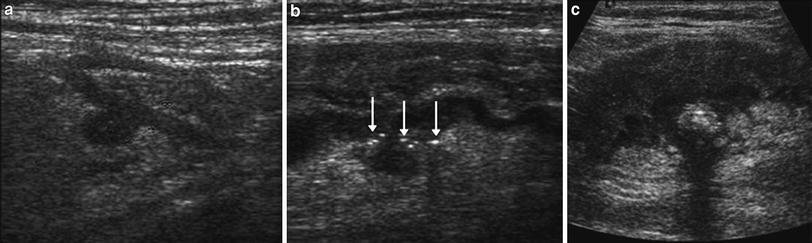

Fig. 3

Transvaginal sonography shows a large echogenic diverticulum (arrows) with a posterior acoustic shadow due to air

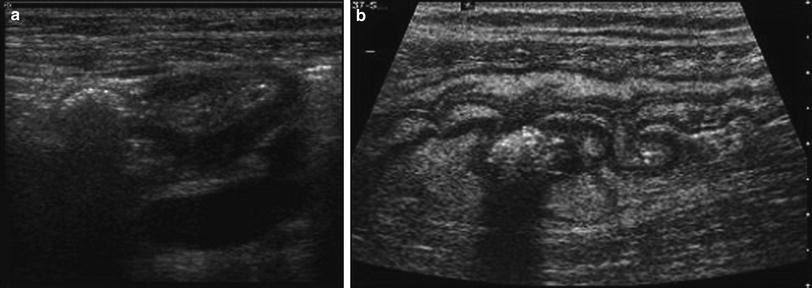

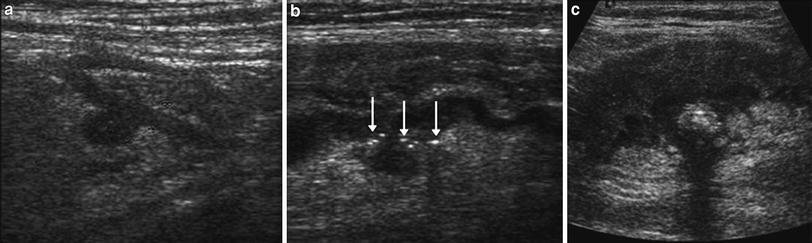

The sonographic appearance depends on the content of the diverticula. In most cases, the diverticula appear hyperechoic because of the air inside. Such echoic diverticula show typical air artefacts up to complete acoustic shadowing. Hyperechoic diverticula with clear acoustic shadowing are typical for a faecolith inside of the diverticulum (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4

Sigmoid colon with echogenic diverticulum. a Tansverse section with a large echogenic diverticulum. Note the muscular layer of the sigmoid colon (hypoechogenic rim) showing hypertrophy. b Longitudinal section showing a diverticulum with an echogenic faecolith inside

The diverticular wall is thin and often not demonstrable at sonography. Large diverticula may be misdiagnosed as haustrations.

In multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT) the air-filled protuberances are usually easier to diagnose than with sonography. Often it is difficult sonographically to differentiate small faecoliths from air within diverticula.

In a study, the accuracy of sonography in diagnosing diverticulosis was approximately 60 % (Hollerweger et al. 2002).

3 Diverticulitis

Acute colonic diverticulitis is a common cause of acute abdominal symptoms, especially in elderly patients. In turn, diverticulitis develops in 10–25 % of the population with diverticulosis (Roberts et al. 1995).

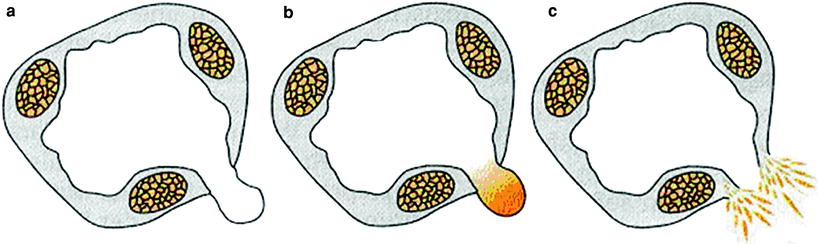

It is, in virtually all cases, the result of a microperforation of a single diverticulum (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5

Diverticulum (a) with inflammation (b) and perforation with peridiverticulitis (cischaemia). In case of inflammation the diverticulum becomes obstructed by impacted stool in its neck. This faecolith abrades the mucosa and causes low-grade inflammation, blocking drainage even further. The obstruction may then cause an expansion of the normal bacterial flora, diminished venous outflow with localised and altered mucosal defence mechanisms, allowing bacteria to breach the mucosa and extend the process through the full wall, ultimately leading to perforation. The term “perforated” diverticulitis should be reserved for cases in which a peridiverticular abscess has ruptured into the peritoneal cavity and caused a purulent peritonitis

The clinical diagnosis and assessment of acute colonic diverticulitis can be difficult (Chappuis and Cohn 1988). The classic pattern of left lower quadrant pain, tenderness, fever and leukocytosis is suggestive of acute colonic diverticulitis but can be mimicked by numerous acute abdominal conditions. Symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, constipation or diarrhoea lead to a high rate of wrong diagnosis up to 34 % of cases.

Dysuria and urinary frequency and urgency may occur if the affected colonic segment lies close to the urinary bladder, and afferent visceral nerves from the inflamed colon, by way of the sacral plexus, may carry referred pain to the scrotum or suprapubic region.

If nearby organs become involved, or if an abscess ruptures into a nearby organ, a fistula may result. Colovesical fistulae are the most frequent type, followed by colovaginal and, less commonly, by colocutaneous fistulae.

Although 85 % of cases of diverticulitis occur in the sigmoid and descending colon, diverticula may be found throughout the colon. Right-sided diverticulitis occurs with greater frequency in Asians and tends to follow a more benign course than that which occurs on the left side (Wada et al. 1990).

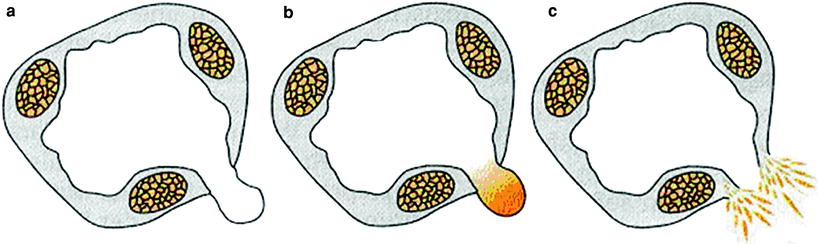

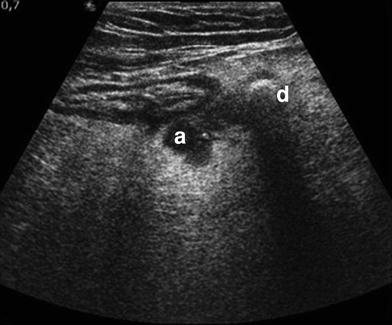

In acute colonic diverticulitis, ultrasound can evaluate the disease with the same four criteria used with CT (Wilson and Toi 1990): (a) thickening of the bowel wall, (b) diverticula, (c) the echogenicity of these foci varying from hypoechoic (Fig. 6a to predominantly hyperechoic with a surrounding hypoechoic rim (Fig. 6b and hyperechoic with or without internal acoustic shadowing (Hollerweger et al. 2001); and (d) inflammatory pericolonic fat frequently recognised as an adjacent hyperechoic halo. Small air bubbles can be visualised as a sign for microperforation (Fig. 6c; therefore sonographic demonstration of extraluminal hyperechoic foci indicates mesenteric gas.

Fig. 6

Acute colonic diverticulitis. a Hypoechoic diverticulum with a surrounding moderate echogenic inflammation. b Longitudinal section of the sigmoid colon shows an echo-poor diverticulum with surrounding little air spots (arrows) as sign for microperforation. c Extensive inflammatory thickening of the sigmoid colon with an echogenic faecolith in the diverticulum

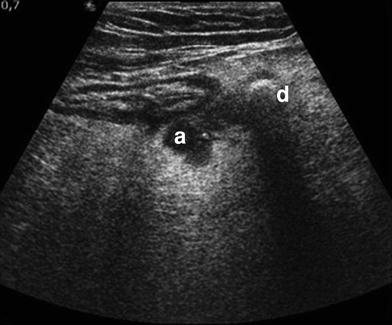

Longitudinal, linear echogenic tracts are suggestive of fistulous tracts. Thickening of the sigmoid colon along with the roof of the bladder and air within the bladder are signs highly suggestive for a fistula into the bladder. Sonography can be limited for assessing large and complex abscesses (Fig. 7). Overall the accuracy of sonography in diagnosing diverticulitis is more than 90 % (Hollerweger et al. 2001; Gritzmann and Hübner 2006; Laméris et al. 2008).

Fig. 7

Echoic diverticulum (d) with a nearby small peridiverticular hypoechogenic abscess (a)

Transrectal (Fig. 8) or endovaginal (Fig. 3) sonography can increase the sensitivity of ultrasound when the distal sigmoid or the small pelvis is affected (Hollerweger et al. 2000; Hollerweger 2007). This localisation is frequently obscured by overlaying bowel-loops gas in transabdominal sonography.