Early evaluation of patients with suspected UC

Evaluation of extension

Assessment of activity

Assessment of short-term response to therapy

Long-term prediction of UC outcome (relapse/remission)

Diagnosis of abdominal complications

Toxic megacolon

Massive pseudopolyposis

Differential diagnosis in chronic inflammatory colitis

2 Clinical and Pathological Features

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic idiopathic inflammatory disease of unknown origin. Depending on the extension and activity, the presence and severity of leading symptoms of the disease such as diarrhoea, rectal blood loss, abdominal pain and fever, can vary and laboratory parameters of the acute phase response (e.g. C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, faecal calprotectin) may be normal or abnormal. These findings usually depend on the severity and extent of colonic involvement.

Ulcerative colitis involves the rectum and extends proximally to all or different portions of the colon (ulcerative proctitis, sigmoiditis, left-sided colitis or pancolitis). Rectosigmoid involvement is present in almost all patients at endoscopy, with approximately 40–50 % of patients having disease limited to the rectum and rectosigmoid, 30–40 % disease extending beyond the sigmoid colon but not involving the entire colon and 20 % total colitis. Mucosal inflammation of the terminal ileum, the so-called backwash ileitis, is observed in up to 20 % of patients with pancolitis, but rarely in patients without caecal involvement. However, involvement of the appendix as a skip lesion is reported in up to 75 % of patients with UC, and the patchy inflammation in the caecum (the so-called “caecal patch”) may also be observed in patients with left-sided colitis, but both these conditions do not seem to be associated with a worse disease outcome.

Proximal spread of the disease, from the rectum to the caecum, occurs in continuity without areas of uninvolved mucosa. However, macroscopical sparing of the rectum has been described in children presenting with UC prior to treatment. In adults, normal or patchy inflammation of the rectum is likely to be due to topical therapy and although macroscopic activity may suggest skip areas, endoscopic biopsies from mucosa with a normal appearance are usually abnormal.

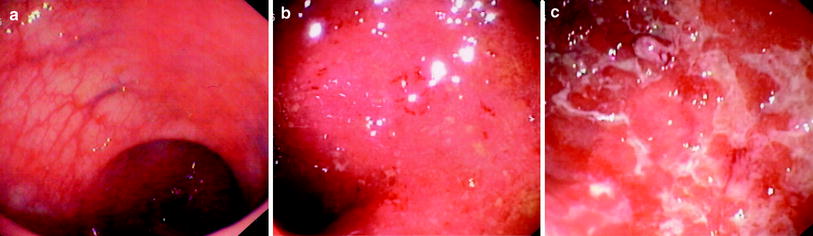

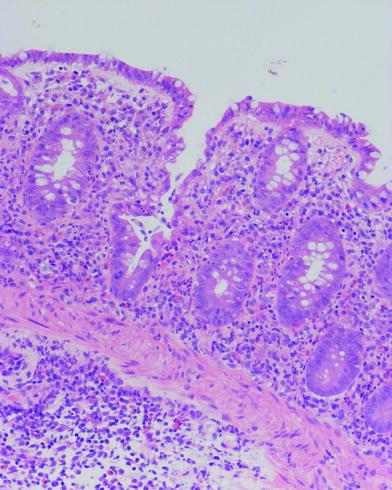

Indeed, the mucosa may appear normal when disease is in remission, whereas with mild and moderate inflammation it is erythematous and of granular appearance. In more severe cases, the mucosa is ulcerated and haemorrhagic (Fig. 1). In long-standing disease, the mucosa may appear atrophic and inflammatory polyps or pseudopolyps may be present as a result of epithelial regeneration.

Fig. 1

Different endoscopic aspects of colon in ulcerative colitis. a Inactive disease: presence of distorted mucosal vascular pattern without ulcerations, friability or spontaneous bleeding. b Moderate disease: marked erythema, absent vascular pattern, friability, coarse granularity with small erosions. c Severe disease: gross ulceration and spontaneous bleeding

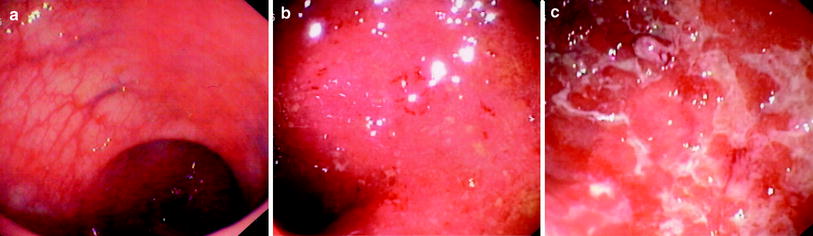

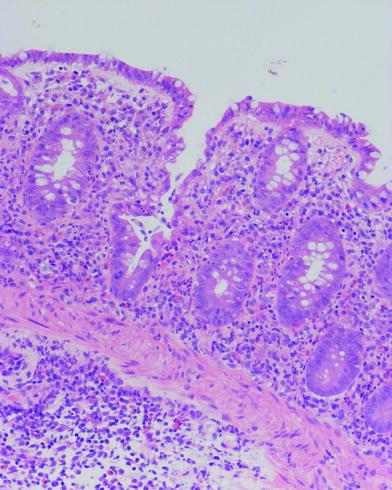

In UC, histological changes are limited to the mucosa and superficial submucosa with deeper layers being unaffected, except in fulminant colitis. The major changes are distortion of crypt architecture and basal plasma cells and basal lymphoid cell infiltrate. Mucosal vascular congestion with oedema, focal haemorrhage and inflammatory cell infiltration may also be present (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2

Histological feature of ulcerative colitis. Changes are limited to mucosa (muscularis mucosae is normal) and consist in distortion of crypt architecture, vascular congestion of mucosa, oedema and basal inflammatory cell infiltrate

These histological changes, as well as endoscopic features, correlate well with sonographic images. However, since the disease is confined to the inner layers of the colon, endoscopy alone may be sufficient to detect and assess the extent and activity of the disease in UC, unlike CD. In this context, the role of cross sectional imaging, US included, may be marginal although useful, in some instances, since it can be repeated and is non-invasive.

3 Ultrasonographic Features of Bowel Walls

The US features of UC include bowel wall thickening, alterations of the bowel wall echopattern, hyperaemia and loss of haustra coli. Occasionally mesenteric hypertrophy and mesenteric lymph nodes, or complications such as stenosis or toxic megacolon, can be found.

Ultrasonographic features of bowel wall, and particularly bowel wall thickening, largely depend on the activity of the disease. In active UC patients, US frequently reveals thickened bowel walls, usually >4 mm, frequently ranging from 5 to 7 mm, rarely >10 mm (Worlicek et al. 1987; Valette et al. 2001; Fig. 3).

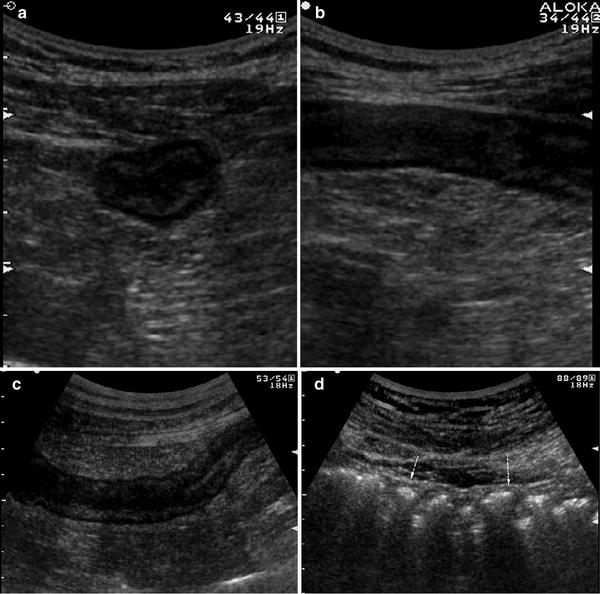

Fig. 3

Ultrasonographic features of bowel wall in patient with ulcerative colitis. Transverse (a) and longitudinal (b) sections of descending colon in patient with left-sided active ulcerative colitis. Thickened bowel walls characterised by stratified echopattern and absence of haustra coli (c) in the left colon. The presence of haustra coli (arrows) in the transverse colon (d) defines the extension of the disease

However the abnormal thickening of bowel walls at US (bowel wall thickness >4 mm) is not specific, since several intestinal disorders, including UC, are characterised by US thickening of bowel walls. The degree of thickness in UC depends on disease activity, being greater in active disease and normal in the quiescent phases (Fig. 4).

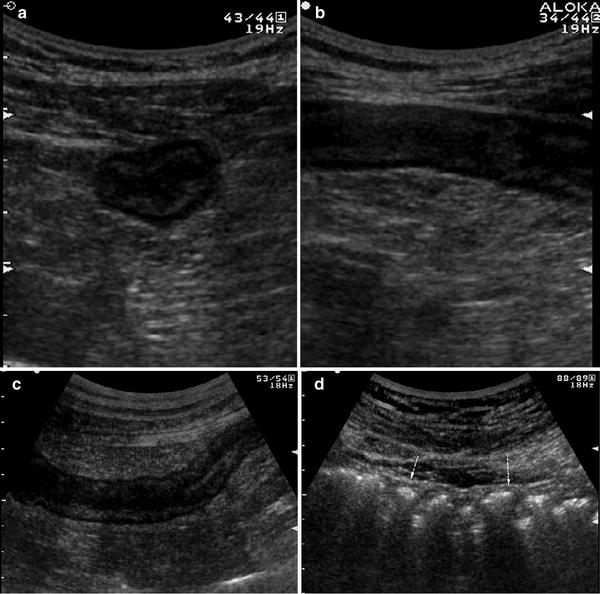

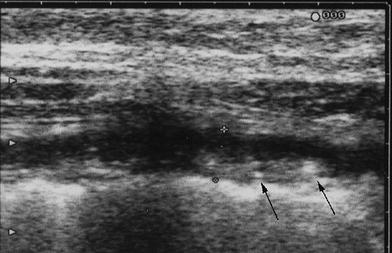

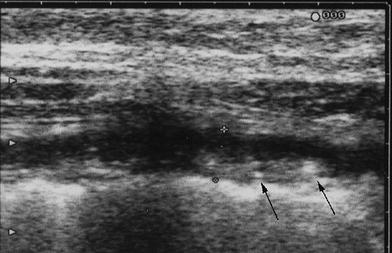

Fig. 4

Longitudinal ultrasonographic sections of descending colon in patients with a active and b non-active UC. Note the increased thickness and hypoechoic echopattern in patient with active disease and normal-appearing aspect of bowel wall (arrows) in patient with quiescent disease

Sonographic diagnosis of UC relies on different features of the bowel wall. In UC, the thickness of the bowel wall is usually homogeneous and continuous, predominates in the left colon and is, therefore, usually found in the left iliaca fossa and in the hypogastric region and extends throughout the entire colon in pancolitis (Fig. 5). Loss of haustration is a frequent finding in active and extensive disease. The thickness of the bowel wall is circumferential and symmetrical.

Fig. 5

Ultrasonographic features of pancolitis. Homogeneous and continuous thickening of the colonic walls with preserved stratified echopattern in a hypogastric region and left iliaca fossa, which extends throughout the entire colon up to b ascending colon and c caecum

Since inflammation involves the mucosa and the superficial submucosa, the stratified echopattern of the bowel wall is usually preserved (Fig. 5). However, in cases of acute inflammation, the thickening involves the submucosa which may appear slightly hypoechoic and dishomogeneous, sometimes giving the bowel wall the US appearance of pathological wall thickening with loss of stratification, with increased bowel wall vascularity (Fig. 6).

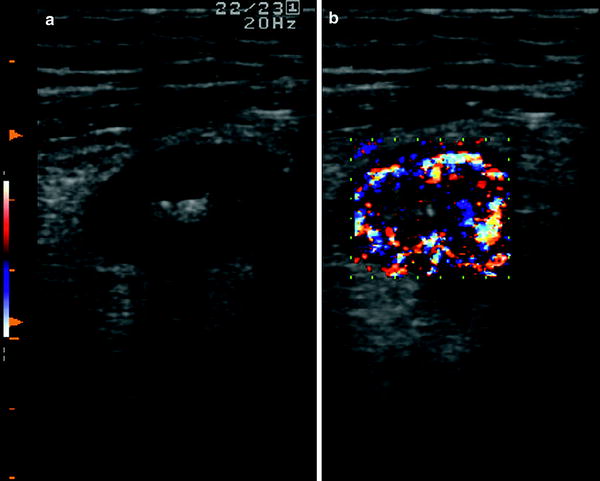

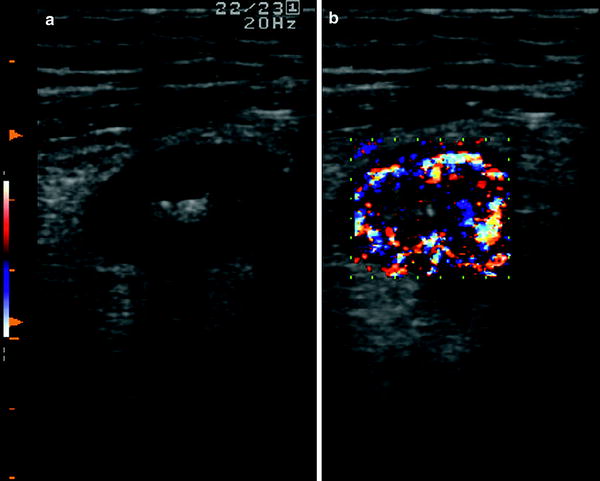

Fig. 6

Ultrasonographic aspect of bowel wall in patient with active ulcerative colitis. The thickening involves the submucosa which may appear slightly hypoechoic (a), with increased bowel wall vascularity (b)

The muscularis propria, which is imaged at US as an external hypoechoic line is preserved, therefore external profiles of the bowel walls in UC are usually linear and regular (Fig. 5).

Unlike CD, ulcerations are superficial and, therefore, not usually revealed by US. No deep or penetrating ulcers are present, except in severe UC in which a pre-perforative laceration of the submucosa is found. Therefore, in mild to moderate active UC, the inner layers of the colonic wall are usually regular. On the contrary, in severe active disease, the inner layer may be regular or even irregular with fine multiple hyperechoic spots, representing deep penetrating ulcers, but within a severely thickened and hypoechoic bowel wall (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7

Severe active UC showing severely thickened and hypoechoic bowel walls, with irregular inner layer due to fine multiple hyperechoic spots, representing deep penetrating ulcers (arrows)

Since the colon returns, at endoscopy, to a normal appearance after resolution of inflammation, US also reveals a normal colonic wall. Indeed, after several recurrences, in quiescent disease, as well as in some cases with mild inflammation, the colonic wall shows normal or only slight thickening with a predominant echogenic submucosa contrasting with the hypoechoic inner mucosa and outer muscularis (Fig. 8).

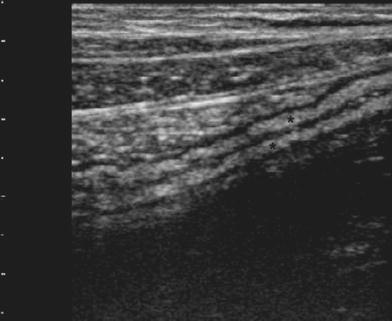

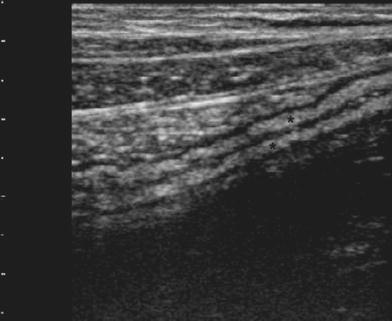

Fig. 8

Quiescent UC, showing colonic wall presenting normal or slight thickening, with a predominant echogenic submucosa (asterisks) contrasting with the hypoechoic inner mucosa and outer muscularis propria

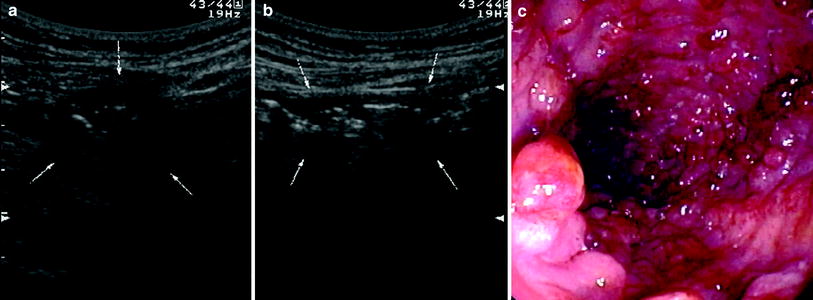

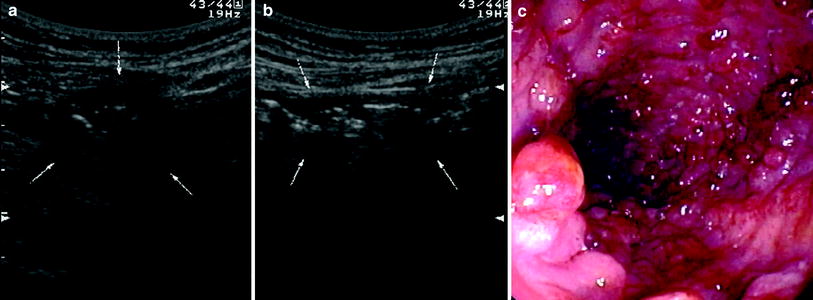

Particular US findings may be observed in UC patients with extensive pseudopolyposis. Pseudopolyps may be observed as small echogenic nodules visible at the surface of the mucosa or echogenic indentations into the fluid-filled intestinal lumen. However, while isolated inflammatory polyps can be detected (Fig. 9), better imaged by hydrocolonic sonography, extensive pseudopolyposis appears as an increased and inhomogeneous thickness of the bowel wall (up to 15 mm) without the typical wall stratification (at least in inactive UC), markedly irregular internal margins and/or as a dilated incompressible bowel with echogenic inhomogeneous content (Fig. 10). To obtain confirmation of the pseudopolypoid nature of the intestinal content, colour-power Doppler can be used to assess the blood flow within the echogenic material.

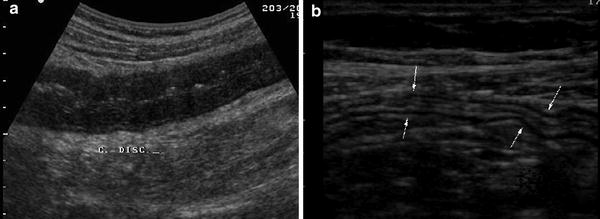

Fig. 9

Ultrasonographic findings in UC patient with pseudopolyposis. Note the slight thickness of sigmoid colonic wall (arrows), with irregular internal margins due to presence of two hypoechoic lesions corresponding to inflammatory peudopolyps (asterisks)

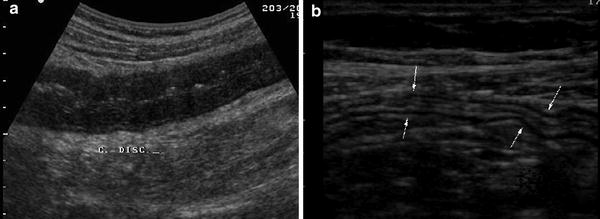

Fig. 10

Ultrasonographic (a, b) and endoscopic (c) findings in UC patient with extensive pseudopolyposis. Note inhomogeneous thickness of distal descending colon at US without typical wall stratification. a Bowel was also incompressible with echogenic inhomogeneous content

4 Detection and Assessment of Extension

The US diagnosis of UC relies upon the above-mentioned findings, mainly upon visualisation of bowel wall thickening greater than 4 mm.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree