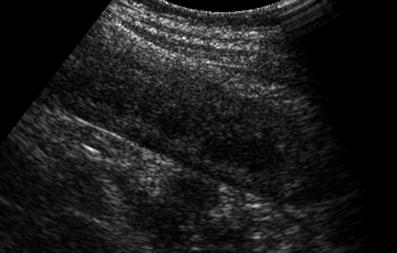

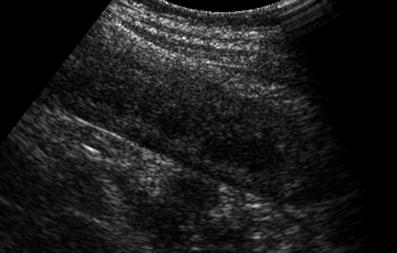

Fig. 1

Sagittal views of the left colon in a severe form of PMC. a B-mode sonogram showing hypoechoic, nodular and diffuse thickening of the haustral relief of the colic wall; b Discrete mural flow of the thickened colic wall is observed in the same patient when color Doppler evaluation is performed. On both images, there is a mild hyperechogenicity of the pericolic fat tissue

Specific sonographic findings related to PMC include pronounced colic wall thickening related to edema of the haustral folds and giving the “accordion sign” or a “gyral” pattern (Fig. 2) (O’Malley and Wilson 2003). The lumen of the colon is narrowed and the submucosa appears as congestive due to the acute inflammation of the colic wall (Frisoli et al. 2000; O’Malley and Wilson 2003). The wall thickness is ranging from 10 to 30 mm (mean 11 mm) (Downey and Wilson 1991; Truong et al. 1998). Despite the increased wall thickness, the colic wall stratification is usually preserved (Fig. 3) (Truong et al. 1998). Reduced or absent mural flow is noted and ascites is present in 30–77 % of the cases (Downey and Wilson 1991; Truong et al. 1998; Ledermann et al. 2000). Infiltration of the pericolic fatty tissue is noted in 50 % of the cases (Truong et al. 1998).

Fig. 2

PMC affecting the right colon. Transverse view on B-mode imaging showing the “accordion sign” related to edema of the haustral folds

Fig. 3

PMC of the right colon. Thickening of the colic wall with preserved wall stratification

A prospective study evaluating sonography as a first line method for the detection of PMC has shown a sensitivity of this technique of 78 % for the diagnosis of PMC and a specificity of 94 % (Gallix et al. 1997). In this setting, relevant sonographic signs were the increased wall thickness, the hyperechoic thickening of the submucosa, and the presence of the “accordion sign”. At the opposite, mural vascularization, pericolic wall changes, and presence of ascites were not demonstrated to significantly contribute for the positive sonographic diagnosis of PMC.

PMC can be differentiated from other colitides (ischemic colitis and inflammatory colitis) when colic wall changes are evaluated. These sonographic colic wall changes include the wall thickness, the presence of wall stratification, detection of mural flow, the visualization of the haustration, and the localization of the disease along the colon (Table 1) (Truong et al. 1998; Danse et al. 2004, 2005).

Table 1

Synoptic view of the main sonographic findings used for the differential diagnosis of acute diseases of the colon

Localization | Thickness (mm) | Stratification | Mural flow (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Crohn colitis | Right colon | <13 | Preserved | 100 |

Ulcerative colitis | Left colon | <9 | Preserved | 100 |

PMC | Left colon | 11 | Absent / Preserved | – |

Infection | Right colon | 9 | Preserved (apart neutropenic colitis) | 90 |

Ischemic colitis | Left colon > Right colon | 9 | 50 % | 60 |

Malignancy | Anywhere | >12 | 20 % | 80 |

In comparison with PMC, which is more frequently seen on the left colon, acute forms of Crohn’s disease have a predisposition for the right colon, are associated to a wall thickness lower than 13 mm, have a preserved stratification, with visualization of the haustral folds and an increased mural flow when color Doppler study of the colic wall is performed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree