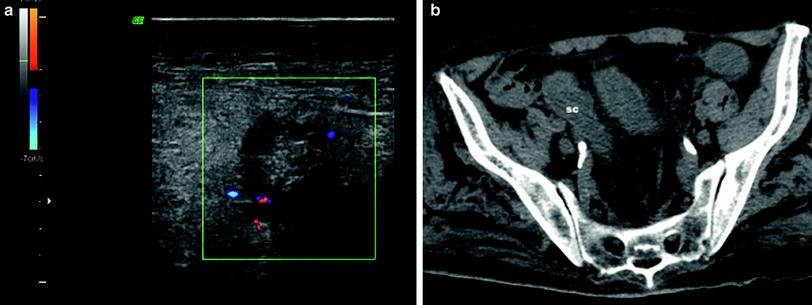

Fig. 1

Ischemic colitis in a young woman (drug addict). a Sonogram of the left colon showing a diffuse hypoechoic thickening of the colic wall, without stratification. b Preserved mural flow is demonstrated with color Doppler sonography

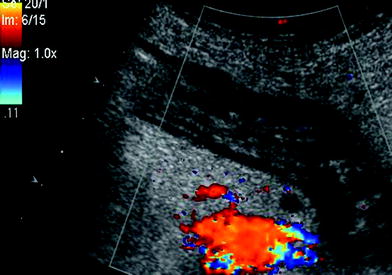

Fig. 2

Ischemic colitis in a 82-year-old patient. a Transverse view of the sigmoid colon showing thickening of the colon, with wall stratification and discrete mural flow detected with color Doppler sonography. The pericolic fat tissue is slightly infiltrated. b CT scan of the pelvis of the same patient showing diffuse thickening of the sigmoid colon

When sonography is considered as the initial diagnostic method for ischemic colitis, it is associated with a sensitivity of 93 % for the adequate recognition of suggestive sonographic signs (Ripolles et al. 2005). Additionally, disappearance of the wall stratification and absence of mural flow are indicators of the severity of ischemic colitis with a sensitivity of 82 % and a specificity of 92 % (Danse et al. 2000a, 2004; Jeffrey et al. 1994; Cheung et al. 1992). Hyperechogenicity of the pericolic fatty tissue can be detected with sonography in patients with ischemic colitis. This sign has to be considered as a severity factor of ischemia as well as the absence of mural flow (Fig. 3) (Ripolles et al. 2005). Predisposing factors can be detected with sonography when stenoses and/or occlusion of the main splanchnic arteries are visualized (celiac trunk, superior and inferior mesenteric arteries) (Danse et al. 2001). Splanchnic vascular insufficiency requires stenosis or occlusion of at least two of the three splanchnic arteries. Significant stenosis of the celiac trunk is present when the maximal systolic velocity is higher than 1.5 m/s. Superior and inferior mesenteric arteries are considered as significantly stenosed if the maximal systolic velocity is higher than 2.75–3 m/s (Bowersox et al. 1991). Sonography has been recently reported as useful for the follow-up of the patients, by showing disappearance of the colic wall changes (Ripolles et al. 2005).

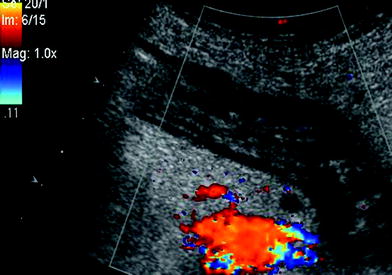

Fig. 3

Ischemic colitis with preserved wall stratification but without any mural flow. Infiltration of the pericolic fat tissue. Resection was performed in emergency, revealing extended necrosis of the left colon

4 Computed Tomography Findings

Thickening of the colic wall related to ischemic colitis is visible with CT, within the same values than sonography (8–9 mm) (Horton et al. 2000; Philpotts et al. 1994). CT findings observed in ischemic colitis are of three types: (a) heterogeneous thickening with hypoperfused areas combined with pericolic fat stranding (40–60 % of the patients), (b) homogeneous thickening without any change of the pericolic fat tissue (33–37 % of the cases), (c) colic pneumatosis within a thin colic wall (6–21 % of the cases) (Balthazar et al. 1999). Ascites is present in less than 30 % of the patients (Balthazar et al. 1999; Philpotts et al. 1994). Severity factors of ischemic colitis at CT are the presence of a thin colic wall, with pneumatosis and reduced or absent colic wall enhancement when iodine contrast injection is performed (Balthazar et al. 1999).

5 Proposed Strategy

When there is a strong suspicion of ischemic colitis, recto-sigmoïdoscopy is performed and can be completed with an abdominal color Doppler study. The role of sonography is to detect the extension of the colitis, and to detect suggestive signs of ischemic colitis (colic wall thickening of the left colon without identifiable mural flow). Prognosis factors are also to look for with sonography, including wall stratification, pericolic fatty tissue hyperechogenicity and ascites. Suggestive predisposing factors like stenoses and/or occlusion of the main splanchnic arteries can also be detected with color Doppler sonography. When sonography is normal or inconclusive, CT is then performed, with intravenous contrast injection if possible.

However, ischemic colitis is a frequent initially unsuspected condition. The radiologist is often the first physician to suggest intestinal ischemia when he identifies a segmental or diffuse colic wall thickening with sonography or CT, in patients for whom cross-sectional imaging studies are required for acute nonspecific abdominal pain. In these cases, when a colic wall change is noted with sonography or CT, the radiologist can suggest ischemic colitis on the basis of the localization of the affected segment, the absence of mural flow or enhancement, visualization of an infiltration of the pericolic fat tissue, pneumatosis, and stenoses or occlusions of the splanchnic arteries. In these initially unsuspected cases, endoscopy is then needed to confirm the ischemic changes of the colic wall (Danse et al. 2005).

References

Balthazar EJ, Yen BC, Gordon RB (1999) Ischemic colitis: CT evaluation of 54 cases. Radiology 211:381–388PubMed

Boley JS (1990) Colonic ischemia-25 years later. Am J Gastroenterol 85:931–934PubMed

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree