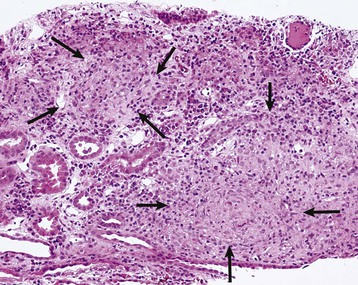

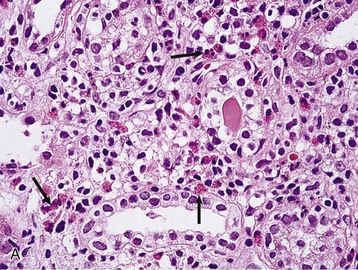

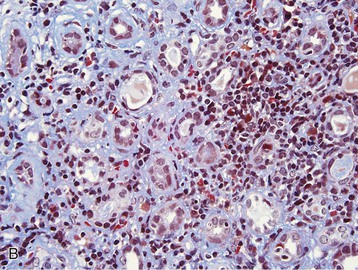

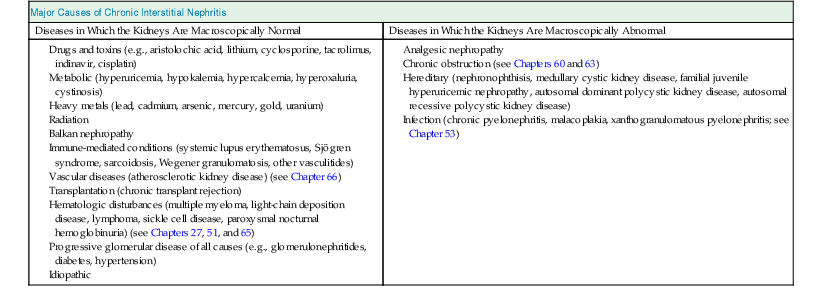

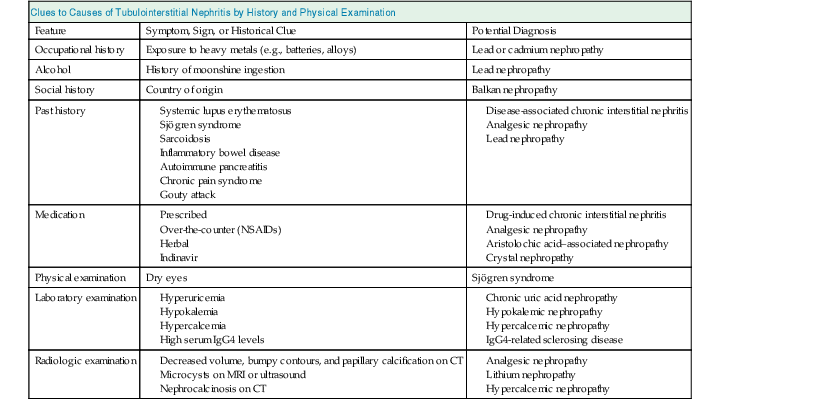

Masaomi Nangaku Chronic interstitial nephritis is a histologic entity characterized by progressive scarring of the tubulointerstitium, with tubular atrophy, macrophage and lymphocytic infiltration, and interstitial fibrosis. Because the degree of tubular damage accompanying interstitial nephritis is variable, the term tubulointerstitial nephritis is used interchangeably with interstitial nephritis. Tubulitis refers to infiltration of the tubular epithelium by leukocytes, usually lymphocytes. There are many primary as well as secondary causes of chronic interstitial nephritis (Table 64-1). Tubulointerstitial injury is clinically important because it is a better predictor than the degree of glomerular injury of present and future renal function. Although any glomerular disease can injure the tubulointerstitium secondarily through mechanisms involving the direct effects of proteinuria and ischemia, in this chapter we discuss only primary chronic interstitial nephritis. Table 64-1 Major causes of chronic interstitial nephritis. Note that kidneys of any clinical entity can be shrunken at end stage. Some diseases categorized as macroscopically normal can in later stages result in macroscopically abnormal kidneys. For example, kidneys of sickle cell nephropathy are macroscopically normal unless papillary necrosis is present. Drugs and toxins (e.g., aristolochic acid, lithium, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, indinavir, cisplatin) Metabolic (hyperuricemia, hypokalemia, hypercalcemia, hyperoxaluria, cystinosis) Heavy metals (lead, cadmium, arsenic, mercury, gold, uranium) Vascular diseases (atherosclerotic kidney disease) (see Chapter 66) Transplantation (chronic transplant rejection) Hematologic disturbances (multiple myeloma, light-chain deposition disease, lymphoma, sickle cell disease, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria) (see Chapters 27, 51, and 65) Progressive glomerular disease of all causes (e.g., glomerulonephritides, diabetes, hypertension) The tubulointerstitium can be injured by toxins (e.g., heavy metals), drugs (e.g., analgesics), crystals (e.g., calcium phosphate, uric acid), infections, obstruction, immunologic mechanisms, and ischemia. Regardless of the initiating mechanism, however, the tubulointerstitial response shows little variation. Tubular injury results in the release of chemotactic substances and the expression of leukocyte adhesion molecules that attract inflammatory cells into the interstitium. Tubular cells express human leukocyte antigens, serve as antigen-presenting cells, and secrete complement components and vasoactive mediators, all of which may further stimulate or attract macrophages and T cells. Growth factors released by tubular cells and macrophages, such as platelet-derived growth factor and transforming growth factor β, may stimulate fibroblast proliferation and activation, leading to matrix accumulation.1 The source of fibroblasts in renal interstitial fibrosis remains controversial but may include an intrinsic fibroblast population, migration of circulating fibrocytes from perivascular areas, and transdifferentiation of tubular cells, pericytes, and endothelial cells into fibroblasts. Over time, a loss of peritubular capillaries and decreased oxygen diffusion caused by expansion of the interstitium render the kidney hypoxic, and progressive apoptosis leads to local hypocellularity and fibrosis.2 Renal function becomes severely decreased, and renal replacement therapies are required. Whereas chronic interstitial nephritis occurs with progressive renal disease of all causes, primary chronic interstitial nephritis is not a common cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD); reports range from 42% in Scotland to 3% to 4% in China and the United States.3–5 This variability in incidence may relate to differences in how diagnoses are made, causes and toxin or drug exposure, and treatment modalities. In several localized regions of the world, marked increases in the incidence of chronic interstitial nephritis have been reported. These include Sri Lanka, some coastal areas of Central America, and the Balkan region in Europe. The pathologic features of chronic interstitial nephritis are nonspecific. They include tubular cell atrophy or dilation; interstitial fibrosis that is composed of interstitial (types I and II) collagens; and mononuclear cell infiltration with macrophages, T cells, and occasionally other cell types (neutrophils, eosinophils, and plasma cells). Tubular lumina vary in diameter but may show marked dilation, with homogeneous casts producing a thyroid-like appearance, hence the term thyroidization. Whereas a noncaseating granulomatous pattern is typical of sarcoidosis, interstitial granulomatous reactions also occur in response to infection of the kidney by mycobacteria (Fig. 64-1), fungi, or bacteria; drugs (including rifampin, sulfonamides, and narcotics); and oxalate or uric acid crystal deposition. Interstitial granulomatous reactions also have been noted in renal malacoplakia, Wegener granulomatosis, and heroin abuse and after jejunoileal bypass surgery. The impaired renal function is often insidious, and the early manifestations of the disease are those of tubular dysfunction, which may go undetected (Box 64-1).6 Diagnosis is often made incidentally on routine laboratory screening or during evaluation of hypertension, in association with reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Proteinuria is commonly less than 1 g/day. The urinalysis may show only occasional white blood cells and, rarely, white blood cell casts. Hematuria is uncommon. Anemia may occur relatively early because of loss of erythropoietin-producing interstitial cells. The tubular dysfunction is often generalized, but some conditions may present with proximal tubular defects including aminoaciduria, phosphaturia, proximal renal tubular acidosis (RTA), or, rarely, a complete Fanconi syndrome. Distal tubular defects can be associated with distal RTA (type 1 or type 4) (see Chapter 12). Concentrating defects (increased urinary frequency and nocturia) can be a sign of medullary dysfunction and may be severe enough to result in nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Some patients will also have an inability to conserve salt on a low-salt diet with a subsequent salt-wasting syndrome. Others, particularly with microvascular disease, may have a relative inability to excrete salt with resultant salt-sensitive hypertension.7 Clues to the causes of tubulointerstitial nephritis by history and physical examination are shown in Table 64-2.8 Table 64-2 Clues to tubulointerstitial nephritis by history and physical examination. CT, Computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. (Modified from reference 8.) Treatment includes identification and elimination of any exogenous agents (drugs, heavy metals), metabolic causes (hypercalcemia), or conditions (obstruction, infection) potentially causing the chronic interstitial lesion. Specific treatments may be required for a condition, such as corticosteroids for sarcoidosis. General measures include control of blood pressure. Most clinicians favor the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), which reduce glomerular and systemic pressures, decrease proteinuria, and increase renal blood flow. Specific therapies for each clinical entity are discussed later. Several drugs and herbs can cause chronic interstitial nephritis. Cyclosporine- and tacrolimus-induced nephropathy is discussed in Chapters 101, 107, and 111; aristolochic acid as a cause of aristolochic acid–associated nephropathy (formerly known as Chinese herbs nephropathy) is discussed in Chapter 78. Lithium is commonly used in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Complications of lithium treatment include nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, acute lithium intoxication, and chronic lithium nephrotoxicity. A meta-analysis of the data of 14 studies involving 1172 patients receiving chronic lithium therapy showed that the prevalence of reduced GFR was 15%.9 Diabetes insipidus results from accumulation of lithium in the collecting tubular cells after entry into these cells through sodium channels in the luminal membrane. Lithium blocks vasopressin-induced reabsorption by inhibiting adenylate cyclase activity, and hence cyclic adenosine monophosphate production, and also by decreasing the apical membrane expression of aquaporin 2, the collecting tubule water channel. Chronic lithium-induced interstitial nephritis may also occur, possibly because of inositol depletion and inhibition of cell proliferation. Biopsies show focal chronic interstitial nephritis with interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy, and glomerular sclerosis. Whereas similar histologic changes have been reported in psychiatric patients without a history of lithium therapy, patients with lithium exposure often show microcystic changes in the distal tubule; interstitial inflammation and vascular changes are relatively minor. The degree of interstitial fibrosis is related to the duration of administration and cumulative dose. The most common presentation of lithium-induced nephrotoxicity is nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, characterized by resistance to vasopressin, polyuria, and polydipsia. Impaired renal concentrating ability is found in about 50% of patients, and polyuria resulting from nephrogenic diabetes insipidus occurs in about 20% of patients chronically treated with lithium. Lithium is also rarely a cause of hypercalcemia, which could potentially exaggerate the tubular concentrating defect and contribute to the development of chronic interstitial nephritis in lithium-treated patients. Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in lithium treatment may be associated with distal RTA, although this partial functional defect is virtually never of clinical importance. Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus induced by lithium may persist despite the cessation of treatment, indicating irreversible renal damage. In one study, the mean serum creatinine concentration of patients with biopsy-proven chronic lithium nephrotoxicity was 2.8 mg/dl (247 µmol/l) at the time of biopsy, and 42% of patients had proteinuria greater than 1 g/day.10 After renal biopsy, all but one patient discontinued treatment with lithium, but seven patients nevertheless progressed to ESRD. A study of 74 lithium-treated patients in France showed that lithium-induced nephropathy developed slowly during several decades, with an average latency between the start of therapy and ESRD of 20 years.11 Magnetic resonance imaging, in particular the half-Fourier acquisition single-short turbo spin-echo T2-weighted sequence, without the use of gadolinium, or ultrasound may help in the detection of the characteristic microcysts in the kidney.12 After other potential causes of polyuria and polydipsia have been excluded, particularly psychogenic polydipsia, the first step to consider is a reduction in lithium dosage. The potassium-sparing diuretic amiloride improves the polyuria and also blocks lithium uptake through sodium channels in the collecting duct. Thiazide diuretics should be avoided because they increase the risk for acute lithium intoxication because of the resultant volume contraction and an increase in sodium and lithium reabsorption in the proximal tubule. Patients undergoing long-term lithium treatment should have renal function and 24-hour urine volume measured yearly (serum creatinine and estimated GFR [eGFR]). Lithium has a narrow therapeutic index, so levels should be monitored and maintained between 0.6 and 1.25 mmol/l. The severity of chronic lithium intoxication correlates directly with the serum lithium concentration and may be categorized as mild (1.5 to 2.0 mmol/l), moderate (2.0 to 2.5 mmol/l), or severe (>2.5 mmol/l). Once-daily regimens are less toxic than multiple daily administration schedules, perhaps because of the possibility of renal tubular regeneration with a once-daily administration schedule.13 Prevention of volume depletion is also important. Because progressive renal injury with reduced GFR in patients without prior acute lithium intoxication is relatively unusual, raised serum creatinine concentration should initially be treated by a dose reduction. If serum creatinine is persistently elevated, a renal biopsy should be considered, although the findings rarely mandate the complete cessation of lithium treatment. At all times, the risk for discontinuation in a patient with a severe unipolar or bipolar affective disorder needs to be balanced with the relatively low risk of progressive renal injury. Analgesic nephropathy resulted from the abuse of analgesics, commonly mixtures containing phenacetin, aspirin, and caffeine, that were available as over-the-counter preparations in Europe and Australia. It is now rare; indeed, some doubt that new cases are still presenting, following restrictions in compound analgesic sales.14 Long-term use of aspirin alone is not associated with analgesic nephropathy, and although long-term nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use has been associated with chronic interstitial nephritis in a small number of patients, a large-scale case-control study found no increased risk of ESRD in users of combined or single formulations of phenacetin-free analgesics.15 A large study in the United States also showed no association between use of current analgesic preparations and increased risk of chronic renal dysfunction,16 although it does increase the risk of acute kidney injury (see Chapter 69). The primary injury in analgesic nephropathy is medullary ischemia caused by toxic concentrations of phenacetin metabolites combined with relative medullary hypoxia, aggravated by inhibition of vasodilatory prostaglandin synthesis. The main pathologic consequence is papillary necrosis, with secondary tubular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis, and a mononuclear cellular infiltrate (Fig. 64-2). Analgesic nephropathy is five to seven times more common in women than in men. Renal manifestations are nonspecific and consist of slowly progressive chronic kidney disease (CKD) with impaired urine concentrating ability, urinary acidification defects, and impaired sodium conservation. Urinalysis shows sterile pyuria and mild proteinuria. Patients with analgesic nephropathy are at increased risk for transitional cell carcinoma of the uroepithelium. Recent prospective analysis of the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study also showed association of regular use of nonaspirin NSAIDs with an increased renal cell carcinoma risk, whereas aspirin and acetaminophen use were not.17 Papillary necrosis is present histologically in almost all patients, but it can be detected radiologically only if part or all of the papilla has sloughed. Papillary necrosis is not pathognomonic of analgesic nephropathy; it is also seen in diabetic nephropathy (particularly during an episode of acute pyelonephritis), sickle cell nephropathy, urinary tract obstruction, and renal tuberculosis. Non–contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) demonstrates a decrease in renal mass with either bumpy contours or papillary calcifications (Fig. 64-3; see also Fig 52-3, C).18

Chronic Interstitial Nephritis

Definition

Major Causes of Chronic Interstitial Nephritis

Diseases in Which the Kidneys Are Macroscopically Normal

Diseases in Which the Kidneys Are Macroscopically Abnormal

Pathogenesis

Epidemiology

Pathology

Clinical Manifestations

Clues to Causes of Tubulointerstitial Nephritis by History and Physical Examination

Feature

Symptom, Sign, or Historical Clue

Potential Diagnosis

Occupational history

Exposure to heavy metals (e.g., batteries, alloys)

Lead or cadmium nephropathy

Alcohol

History of moonshine ingestion

Lead nephropathy

Social history

Country of origin

Balkan nephropathy

Past history

Medication

Physical examination

Dry eyes

Sjögren syndrome

Laboratory examination

Radiologic examination

Treatment

Drug-Induced Chronic Interstitial Nephritis

Lithium Nephropathy

Definition and Epidemiology

Pathogenesis

Pathology

Clinical Manifestations

Lithium-associated Diabetes Insipidus

Chronic Lithium Nephropathy

Treatment

Analgesic Nephropathy

Definition and Epidemiology

Pathogenesis and Pathology

Clinical Manifestations

Diagnosis

Chronic Interstitial Nephritis

Chapter 64