Fig. 17.1

This shows the distribution of erosions by consecutive series of hundred cases of LAGB Bands performed. Most erosions occurred early in the learning curve, peaking at a rate of 19 %, but now falling to below 1 %

17.4 Clinical Presentation

The clinical manifestations of band erosion are summarized in Table 17.1. The characteristic features of band erosion include of a loss of satiety, weight gain, and a need for a steadily increasing band fill volume in an effort to control appetite. In this series, initial appearance of erosion occurred at a mean time interval 24.5 months (SD 20.7, range 1.3–95.5 months) after band placement [20] and 4.5 ± 3.7 months before diagnosis [8]. Those with a perigastric approach present later compared to the pars flaccida approach (43 months vs. 20 months) [8].

Symptom | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

Satiety | |

Loss of satiety | 83 |

No change in satiety | 14.1 |

Weight gain | |

Weight regain | 64 |

Weight Loss maintained | 27 |

Abdominal pain | |

Site: Epigastric | 45 |

Left upper quadrant | 35 |

Epigastric, Left upper quadrant | 25 |

Left flank | 5 |

Port Fluid Characteristics | |

Need for increasing band volume | 78 |

Missing volume | 22 |

Gastric fluid | 19 |

Air on aspiration (>1 ml) | 2 |

Port Issues [8] | |

Spontaneous infection | 21 |

Extrusion of port | 3 |

Port site tenderness | 1 |

Vomiting | 22 |

Anemia | 14 |

Heartburn | 10 |

Hematemesis | 5 |

Dysphagia | 3 |

The patient with an eroded band complains of a gradual loss of satiety and subsequent weight regain [20]. The loss of satiety typically results in the managing physician steadily adding fluid to the band during a lead period that averages of 36 months prior to endoscopic diagnosis of erosion. This is associated with a mean weight gain of 2.3 BMI units, starting at an average 9 months prior to endoscopic confirmation of the diagnosis of erosion [20]. Late, spontaneous infection of the access port may occur in 21 % of patients and should invariably lead to a search for band erosion using endoscopy. While most patients present with a range of benign symptoms such as decreased satiety, about 5 % present to the emergency room with hematemesis [21–23].

17.5 Diagnosis

A diagnostic workup to look for erosion should be prompted by the appearance of the abovementioned clinical features. The long delay between the onset of symptoms and eventual diagnosis is in keeping with its characteristically benign and insidious presentation. Gastroscopy remains the definitive diagnostic tool. While the diagnosis is confirmed by intragastric visualization of the LAGB at endoscopy (Fig. 17.2a), radiologic imaging, especially with a barium meal or a CT scan, can occasionally reveal pathognomonic features (Fig. 17.2b) [24]. However, sensitivity of an imaging is very poor at only 8 %.

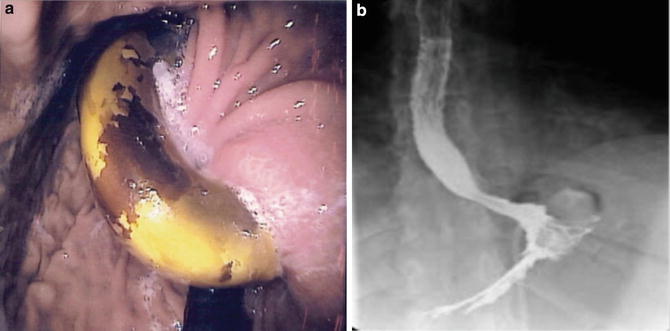

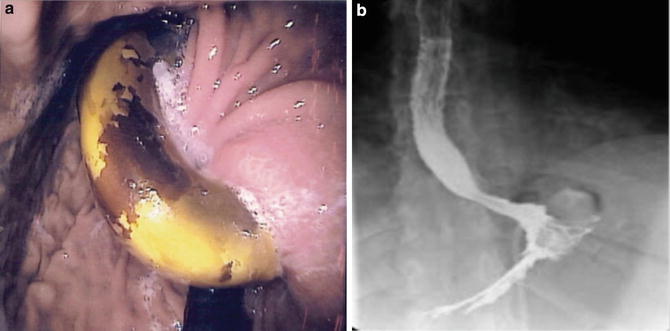

Fig. 17.2

Figure (a) shows a band eroding into the gastric lumen, losing its ability to cause restriction. Figure (b) shows the rare instance with contrast outlining part of an intraluminal band. It is unusual to see a diagnostic barium meal even in the presence of complete erosion into the stomach. Courtesy of P. E. O’Brien, MD

The diagnosis of erosion is sometimes made intraoperatively, in 5 % of patients who either undergo emergent surgery for hematemesis or for removal of a prolapsed band. Endoscopic diagnosis is typically made at a median 32.2 (range 24–58) months from band placement, with the interval from first clinical manifestation to eventual endoscopic diagnosis a median of 10.7 (range 1.6–27.8) months.

17.6 Management

There are two issues to be considered in the management of band erosion. The first relates to the management of the erosion itself while the second concerns the choice of a subsequent weight loss procedure. The eroded band may be removed surgically or endoscopically, while the options for the subsequent obesity intervention range from primary or staged band replacement to use of an alternate bariatric procedure such as a sleeve gastrectomy or gastric bypass. Clearly, it is also an option to pursue dietary and behavioral management alone, if the patient is uninterested in or unable to undergo further surgery.

17.7 Surgical Explantation

Surgical explantation of an eroded band can be achieved laparoscopically, utilizing previous port sites one of which will typically be a 15 mm port. Despite the frequent presence of adhesions between the left lobe of the liver and the anterior gastric wall, the left subcostal area is often free of adhesions. A CO2 pneumoperitoneum to 15 mmHg can be safely achieved using a 5 mm left subcostal optical trocar. Under direct vision, using a 5 mm 30-degree laparoscope, a 15 mm port is placed about 15 cm beneath the xiphisternum just to the left of the midline. Two 5 mm ports are then introduced, one at the left subcostal anterior axillary line and the second at the right subcostal and mid-clavicular lines. It is expected that there will be significant adhesions between the left lobe of the liver and the anterior gastric wall, which will require careful mobilization. This can be facilitated by use of a Nathanson liver retractor and a steep reverse Trendelenburg position.

With the patient in reverse Trendelenburg position, the tubing of the lap band is identified and divided as it enters the peritoneal cavity from the access port. The proximal end can be used as a guide to the band and its buckle. It is traced through the inflammatory mass or adhesions to the upper anterior gastric wall. Using an L-hook cautery or ultrasonic shears, the pseudocapsule and gastrogastric sutures are divided to expose the lap band . If the anterior portion of the band is completely intragastric, a small gastrotomy will need to be created anteriorly just below the buckle in order to allow access to the intraluminal band. When a portion of the band is still extra-gastric anteriorly, simply incising the pseudocapsule will expose the band. Using endoshears, the exposed band is divided thus permitting its removal from within the stomach. The gastric defect in the stomach can be closed with interrupted 2–0 absorbable sutures. The band and tubing are then removed from the peritoneal cavity through the 15 mm port. Copious irrigation is carried out and integrity of the closure is confirmed by testing for leaks while insufflating the stomach with air using an orogastric tube or gastroscope. The gastrotomy repair site may be reinforced with fibrin sealant . Additionally, an omental patch may be applied to the area.

A careful inspection should be made of the intraperitoneal tubing prior to conclusion of the procedure as secondary extra-gastric sites of additional erosion may exist [25]. This author (PT) has operated on one patient with intra-gastric band erosion where upon retrieving the band and tubing, a 2″ segment of tubing within an adjacent inflammatory mass on the transverse colon was noted to be stained yellow. Assuming this to be due to erosion of the tubing into the transverse colon, the two exit points of the tubing in this inflammatory mass were sutured using interrupted 2–0 polyglactin suture with an uneventful postoperative course. The incidence of such secondary or extra-gastric erosions remains unknown.

After completion of the exploration, the access port is then removed by dividing its anchoring sutures and applying traction to the port and its attached tubing. The access port site is irrigated and then either left open or loosely closed.

The procedure is generally well-tolerated, although 11 % of patients will develop a superficial surgical site infection [8], usually involving the port through which the port is removed or the site of the access port. Less common complications include wound abscess (4 %) and gastric fistula (2 %) [8]. In our series there were no deaths either in the perioperative period or in the period of follow up (median 44 months after band replacement and 2.5 months after explant only) [20].

17.8 Endoscopic Explantation

The endoscopic approach is less commonly used for removal of an eroded band. Before endoscopic removal of an eroded band can be attempted there are two prerequisites. First, the access port must be removed surgically, leaving the connecting tube in the peritoneal cavity. This procedure can be performed with minimal anesthesia and is usually well-tolerated. Second, the band must show at least 50 % effacement [26, 27]. If this is not the case, the erosion can be given time to mature. Periodic endoscopic surveillance will document progression of the intragastric migration.

The most commonly applied technique for cutting the band endoscopically is the so called butter-wire technique in which a 0.035″ wire is threaded around the eroded band and pulled out through the mouth. In this manner a long wire is placed around the band and both ends can be fed into the crank handle of a mechanical lithotripter. Controlled pressure is applied incrementally until the band material cracks and is transected [28]. The eroded band can then be completely removed in two pieces through the oropharynx with the use of a standard metal snare. It is not necessary to perform any closure after the band is removed as the tract is often formed slowly over many months and there is a cicatricial response. Free perforation into the peritoneal cavity is thus exceedingly rare.

The endoscopic removal of an adjustable band is a minimally invasive technique, which can be performed in a single outpatient session, providing a simple solution to a potentially serious complication. Successful endoscopic removal can be achieved in between 80 and 95 % of patients who meet the criteria noted above [18, 29, 30]. The largest series of endoscopic band removal [18] described 50 cases with successful removal in 46 (92 %), requiring 1–5 endoscopies (median of 1) prior to removal. The median duration of the procedure was 46 min with a range of 17–118 min [18]. Failure to remove the eroded band or other intraoperative events lead to conversion to a formal surgical procedure in the operating room [30].

There is no established algorithm for endoscopic management due in part to its relatively low incidence. Where the erosion is early, with less than 50 % effacement, endoscopic monitoring for progressive effacement may not be without risk especially major hematemesis [23]. Endoscopic needle knife gastrotomy over the partially eroded band has been described as a novel technique to hasten intraluminal effacement [31]. While rare, complications from endoscopic band removal may occur, including bleeding or other adverse events . For this reason, it is advisable to undertake the procedure in the operating theater rather than the endoscopy suite [30, 32]. Pneumoperitoneum requiring surgical decompression [29] and gastric fistula or subcutaneous abscess at the site of the access port have been reported as possible complications of endoscopic explantation. Pain, and sometimes port site infection, can be observed and often managed conservatively.

Endoscopic explantation has not gained widespread popularity outside a small number of centers, in part because of delays in definitive treatment for band effacement and consequent need for multiple endoscopies and anesthesia in addition to the required operative procedure for removal of the access port [33].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree