Fig. 6.1

Population-based trends of various bariatric surgery procedures from California, Florida, and New York. The graph demonstrates the number of cases performed for laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB), laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG), and laparoscopic gastric band placement (LGB) over the last 5 years in California, Florida, and New York

Development of an enteric leak can lead to devastating morbidity as well as significantly increased mortality [8]. Early diagnosis may significantly reduce morbidity and mortality, although the host immunoreactivity triggering the inflammatory response probably plays a larger role than timing of treatment [9]. Patients who develop an enteric leak require additional diagnostic tests, longer duration of hospitalizations, intensive care unit support, prolonged ventilator support, and even additional surgical interventions in some instances. The most common site of an enteric leak following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is the gastrojejunostomy.

The purpose of this chapter is to discuss the presentation and predilection of patients with an enteric leak after RYGB for morbid obesity; assess various methods to prevent enteric leaks; and offer several treatment options to manage these patients.

6.2 Etiology of an Enteric Leak

An anastomotic leak is a disruption of the normal acute healing process, leading to a defect in the new enteric connection. The basic tenets of any anastomotic technique include avoiding excess tension, maintaining adequate blood flow, and providing adequate oxygenation to avoid ischemia [10]. Ischemia may occur secondary to excess mechanical tension, excessive dissection, or preexisting comorbidities, such as atherosclerosis, diabetes mellitus, or coronary artery disease. Other factors that may contribute include previous history of chemotherapy, prior radiation exposure or administration, and use of glucocorticoids.

Patient factors have been implicated in the etiology of enteric leaks. Several studies have identified individual risk factors for major complications following RYGB. Livingston et al. found male gender, revisional procedures, advanced age, and increasing weight to be predictors of major complications after RYGB [11]. Gonzalez and colleagues validated BMI > 50 kg/m2 and revisional procedures to be independent risk factors for postoperative complications [12]. Nguyen et al. confirmed male gender, advanced age, as well as surgeon inexperience (fewer than 75 cases), to have a negative impact on postoperative outcomes following LRYGB [13]. In a study by Fernandez and colleagues of 3000 patients undergoing bariatric procedures, male patients, advanced age, increased weight and those with multiple comorbidities were at increased risk for developing an anastomotic leak [6].

6.3 Presentation and Diagnosis

Over the last two decades, bariatric surgeons have become adept at performing the RYGB. Nevertheless, enteric leaks remain a feared complication in the morbidly obese postoperative patient. Enteric leaks present with some element of peritonitis or sepsis. Clinical signs and symptoms may include fever, tachycardia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, tachypnea, shortness of breath, and/or altered mental status. Laboratory data may demonstrate a leukocytosis. It is imperative that the clinician have a high index of suspicion, as these patients are often difficult to examine given their girth and body habitus. Additionally, many of these patients have multiple comorbidities that may confound the diagnosis. Nevertheless, some patients may be completely asymptomatic. In these cases, additional diagnostic modalities should be investigated.

Some patients may require additional investigative studies to diagnose an enteric leak. Some centers advocate the use of routine postoperative upper gastrointestinal series (UGIS). The sensitivity of detecting a leak is fairly variable, ranging from 22 to 75 % [14]. The variability in sensitivity is multifactorial, attributable to the low quality of radiologic imaging, limited radiologist clinical experience, premature timing of the test, and initial postoperative anastomotic edema of the gastrojejunostomy. Another imaging modality is helical computed tomography (CT) scan. CT scanning has high specificity and low rate of false-negativity for enteric leaks. The major drawbacks to using CT scanning in place of UGIS as a first radiographic test is the higher cost, weight limit of the table, availability of the machine, as well as aperture of the machine. Nevertheless, CT scanning may be necessary as UGIS is not sensitive or specific enough. Furthermore, the clinician must maintain a high index of suspicion, even in the face of a negative UGIS or even a CT scan sometimes.

6.4 Prevention of Enteric Leaks

Any large series of RYGB will report a certain percentage of patients experiencing an enteric leak. The majority of leaks are probably not solely due to technical error, but rather multifactorial, as previously discussed. Various surgical techniques have been reported to decrease the incidence of an enteric leak, including hand-sewing the anastomosis, use of a linear stapler, use of a circular stapler, or some combination of the aforementioned techniques. Moreover, technical modifications have also included oversewing staple lines, reinforcing staple lines, the use of fibrin glue, or the use of other tissue sealants (Table 6.1). At our institution, we perform an intraoperative leak test to assess for any potential leaks. This test is performed with a methylene blue dye instilled into the gastric pouch while the Roux limb is obstructed. Any blue extravasation is considered a positive test for a leak. The test can also be performed with air and the anastomosis can be submerged in irrigation fluid. Any bubbling noted would be considered a positive test as well. Data regarding the efficacy of this technique in preventing enteric leaks are predominantly retrospective, but highly suggestive of being helpful in identifying intraoperative leaks [15, 16].

Table 6.1

Preventative considerations for enteric leaks

Anatomic considerations |

Avoid overdissection of blood supply |

Divide greater omentum |

Score the mesentery |

Retrocolic position |

Stapling considerations |

Linear reinforcement with buttressing material |

Reinforce staple line with sutures |

Fibrin-sealant reinforcement |

6.4.1 Blood Supply and Tension

Maintaining adequate blood supply is essential for prevention of anastomotic ischemia, necrosis, and failure. Careful and meticulous dissection of the left gastric artery branches to the pouch should be preserved. Minimal dissection of the lesser curve and avoiding excessive dissection of the phrenoesophageal ligament will help maintain adequate blood supply to the gastric pouch. Mobilizing the esophagus at the hiatus is another technique to increase esophageal length and decrease tension on the pouch. These points are especially important for patients undergoing a revisional bariatric procedure, i.e., those who previously underwent a sleeve gastrectomy or previously had an adjustable gastric band.

Avoiding tension from the root of the mesentery of the Roux limb facilitates a tension-free anastomosis. The proximal jejunum should be run caudally to a point of tension-free mesenteric mobility, typically between 50 and 100 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz. We routinely divide the greater omentum to within 2 cm from the transverse colon, which is especially helpful in patients with significant intraabdominal fat. The omentum is then divided parallel to the transverse colon to allow an obstructed path of the Roux limb to the gastric pouch in an antecolic, antegastric fashion. This allows confirmation of a gastric pouch with minimal to no tension. If there is any doubt, the mesentery can be scored to further decrease the tension. An alternative approach is a Roux limb placed in a retrocolic position which generally is a shorter path to the proximal gastric pouch and can be a very useful in high-BMI or male patients with a predominance of intra-abdominal and mesenteric fat.

6.4.2 Surgical Techniques

Several techniques have evolved in creation of the gastric pouch and the jejunojejunostomy in patients undergoing RYGB. The choice of anastomotic technique is largely a function of surgeon preference and institutional familiarity. Initial studies over a decade ago by Gonzalez et al. found no difference in leak rate for patients undergoing LRYGB between the hand-sewn, linear-stapled, and circular-stapled anastomosis for the gastric pouch (no leaks occurred in all 87 patients studied), although stricture rates occurred more frequently in the circular-stapled group (31 %) compared to the hand-sewn (3 %) and linear-stapled (0 %) groups (P < 0.01) [17]. Bendewald and colleagues compared a series of 882 consecutive patients undergoing LRYGB for morbid obesity [18]. Three different techniques were performed for creation of the gastrojejunostomy, including hand-sewn, use of a linear stapler, and use of a 25 mm circular stapler. On multivariate analysis, the authors found leak rates of 1.1 % in the hand-sewn group, 1.0 % in the linear stapler group, and no leaks in the circular stapler group (p = 0.48) and concluded that there was no difference in outcomes with respect to anastomotic technique. Stricture rates were also not significantly difference in this study (6.1 % vs. 6.0 % vs. 4.3 %, respectively; p = 0.66). Giordano and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of 1321 patients from eight studies and compared the linear-stapled to the circular-stapled anastomosis during gastrojejunostomy for LRYGB [19]. The primary endpoints were gastrojejunal leak and stricture rates. No technique was superior to the other with respect to leak rate; however, the linear-stapled anastomosis demonstrated a significantly lower risk of stricture (relative risk [RR]: 0.34; 95 % confidence interval [CI]: 0.12–0.93; p = 0.04). Wound infection (RR: 0.38; 95 % CI: 0.22–0.67; p = 0.0008) and operative times (P < 0.0001) were significantly lower with the linear stapler technique as well.

6.4.3 Staple Line Reinforcement

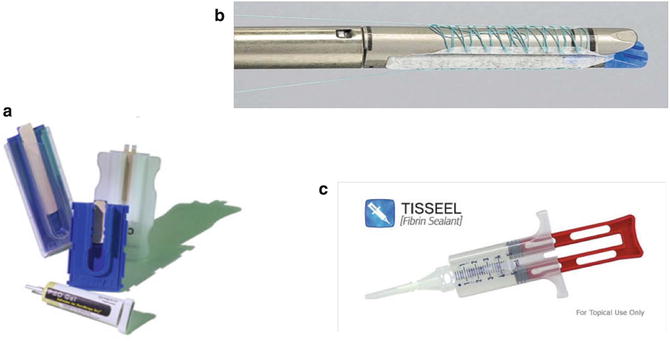

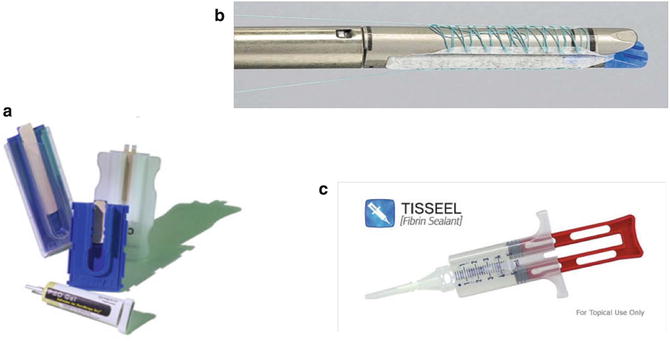

Various tools are available in the bariatric surgeon’s armamentarium to prevent adverse intraoperative and postoperative events, including enteric leaks and bleeding (Fig. 6.2). One of these tools is treated bovine pericardial strips for staple line buttressing. These were first introduced in 1994 in the field of thoracic surgery to decrease the incidence and duration of air-leaks following lung resections [20]. The first major application of this type of product in bariatric surgery was to decrease the incidence of extraluminal bleeding using a linear stapler buttressed with this material. Angrisani et al. performed a prospective randomized control trial of 98 patients undergoing LRYGB for morbid obesity [21]. Fifty patients were randomized to the treated bovine pericardial strips for use with the linear stapler, while the remaining 48 patients had non-buttressed staple lines. The gastrojejunostomy was performed using a circular stapler, but the gastric transection was still performed with a linear stapler. Although the authors focused on extraluminal bleeding, which was significantly lower in the bovine pericardial strip group based on operative time and number of clips used (P < 0.01), the number of positive methylene blue leak tests was 6/48 in the non-buttressed group and 0 in the bovine pericardial strip group (P < 0.0001).

Fig. 6.2

Anastomotic buttressing materials. Panel A shows the bovine pericardial strips. Panel B depicts the absorbable polymer membrane (Bioabsorbable Seamguard, W.L. Gore, Flagstaff, Arizona, USA). Panel C illustrates the fibrin sealant (Tisseel, Baxter Healthcare Corp. ©, Deerfield, IL)

Another prospective randomized control trial using a slightly different product, polyglycolic acid (PGA) and trimethylene carbonate, demonstrated the superiority of the bioabsorbable staple line material during LRYGB for morbid obesity with respect to staple line bleeding [22]. In this study, there were no leaks in either group, but there was one positive methylene blue leak test in the non-buttressed group. Three patients in the non-buttressed group developed gastrogastric fistulas; however, this was not statistically significant (p = 0.20).

Circular stapler reinforcement has also been investigated with respect to enteric leak rates, bleeding, and stricture rates. In a study by Jones and colleagues of 393 patients undergoing LRYGB, the use of bioabsorbable staple line reinforcement (PGA and trimethylene carbonate) for circular staplers was investigated [23]. In this study, 138 consecutive patients underwent bioabsorbable staple line reinforcement for the circular stapler and these were compared to a series of 255 patients without circular staple line reinforcement. There was no significant difference in anastomotic leak rate or bleeding in the buttressed versus the non-buttressed groups (0.7 % vs. 1.9 %, respectively; p = 0.34, and 0.7 % vs. 1.1 %, respectively; p = 0.64). However, the incidence of stricture was significantly higher without the use of a bioabsorbable staple line reinforcement material (9.3 % vs. 0.7 %, respectively; p = 0.0005). Ibele et al. reported on a series of 81 consecutive patients who underwent circular stapled anastomoses using a nonabsorbable buttressing material (bovine pericardium strip) [24]. These patients were compared to a series of 419 patients who underwent circular stapled anastomoses without buttressing material. The leak rate was significantly higher in the buttressed group (4.9 % vs. 0.7 %, respectively; p = 0.02). Moreover, one staple line failure occurred in the buttressed group compared to none in the non-buttressed group. The authors concluded that caution should be taken when using the buttressing material for circular stapled anastomoses, given the staple line failure and enteric leaks.

Another option to reinforce staple lines includes the use of a fibrin sealant . The sealant forms an insoluble polymerized matrix that stabilizes as it adheres to the edges of the gastrojejunal anastomosis, which effectively hinders fibrinolysis by inhibition of the plasminogen–plasmin cascade. This theoretically creates an impermeable seal along the anastomosis. In a large study by Sapala and colleagues of 738 patients, the effects of vapor-heated fibrin sealant was investigated to assess the efficacy in anastomotic leaks at the gastrojejunostomy for patients undergoing RYGB for morbid obesity [25]. A total of 1 mL of vapor-heated fibrin glue was applied to the anastomosis. Two patients developed a leak (0.3 %) compared to their historical control leak rate of 0.9 %. Interestingly, the anastomotic leaks did not occur at the fibrin-sealed gastrojejunostomy sites. Furthermore, no gastrogastric fistulas occurred. In another study of 480 undergoing RYGB for morbid obesity, 120 patients had fibrin sealant applied to the gastrojejunal anastomosis [26]. None of the patients in the fibrin sealant group developed a leak, while 8 of the remaining 360 patients developed an enteric leak requiring either re-operation, a drainage procedure, or long-term parenteral nutrition. A prospective multicenter, randomized trial of 320 patients studying the use of fibrin sealant to prevent major complications following LRYGB demonstrated no significant difference in rate of anastomotic leaks with fibrin sealant application (1 leak in fibrin sealant group vs. 3 leaks in control group) [27]. The early complication rate was not significantly different between the two groups (P > 0.05). However, patients without fibrin sealant application had a significantly higher reintervention rate for early postoperative complications (p = 0.016). There were six patients with gastrojejunal stenosis in each group.

6.5 Management of Enteric Leaks

Management of enteric leaks is dependent on several factors, including the severity and location of the leak. Nevertheless, the mainstay of treatment is surgery and other interventions can be considered on a case-by-case basis. Broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy should be initiated immediately and, dependent on the extent of the leak, the patient should be taken back to the operating room for either diagnostic laparoscopy or exploratory laparotomy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree