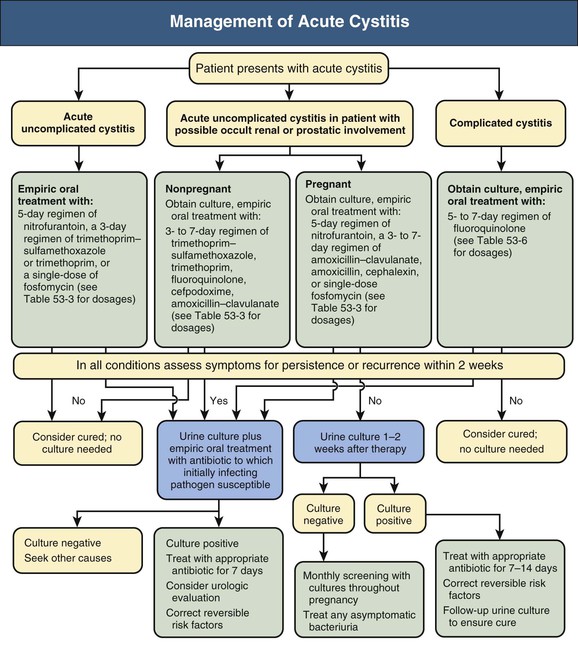

Thomas Hooton Urinary tract infection (UTI) in adults can be categorized into six groups: young women with acute uncomplicated cystitis, young women with recurrent cystitis, young women with acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis, adults with acute cystitis and conditions that suggest occult renal or prostatic involvement, complicated UTI, and asymptomatic bacteriuria (Box 53-1).1 Chapter 44 discusses UTI in pregnancy, and Chapter 63 describes vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) in children. Complicated urinary tract infection is defined as UTI that increases the risk for serious complications or treatment failure. Patients with various conditions, such as those presented in Box 53-1, are at increased risk for complicated UTI. Complicated UTIs may require different pretreatment and post-treatment evaluation and type and duration of antimicrobial treatment than for uncomplicated UTI. On occasion, complicated UTIs are diagnosed only after a patient has a poor response to treatment. Acute uncomplicated UTIs are extremely common, with several million episodes of acute cystitis and at least 250,000 episodes of acute pyelonephritis occurring annually in the United States. The incidence of cystitis in sexually active young women is about 0.5 per 1 person-year.2 Acute uncomplicated cystitis may recur in 27% to 44% of healthy women, even though they have a normal urinary tract.3 The incidence of pyelonephritis in young women is about 3 per 1000 person-years.4 The self-reported incidence of symptomatic UTI in postmenopausal women is about 10% per year.5 The incidence of symptomatic UTI in adult men younger than 50 years is much lower than in women, ranging from 5 to 8 per 10,000 men annually. Complicated UTIs encompass an extraordinarily broad range of infectious entities (see Box 53-1). Nosocomial UTIs are a common type of complicated UTI and occur in 5% of admissions in the university tertiary care hospital setting; catheter-associated infections account for most of the infections. Catheter-associated bacteriuria is the most common source of gram-negative bacteremia in hospitalized patients.6 Asymptomatic bacteriuria is defined as two separate consecutive clean-voided urine specimens, both with 105 or more colony-forming units per milliliter (cfu/ml) of the same uropathogen in the absence of symptoms referable to the urinary tract.7 Asymptomatic bacteriuria is found in about 5% of young adult women,8 but rarely in men younger than 50. The prevalence increases up to 16% of ambulatory women and 19% of ambulatory men older than 70 and up to 50% of elderly women and 40% of elderly men who are institutionalized.7 Asymptomatic bacteriuria may be persistent or transient and recurrent, and many patients have had previous symptomatic infection or develop symptomatic UTI soon after having asymptomatic bacteriuria. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is generally benign, although it may lead to serious complications in some clinical settings. Most uncomplicated UTIs in healthy women result when uropathogens (typically Escherichia coli) present in the rectal flora enter the bladder through the urethra after an interim phase of periurethral and distal urethral colonization. Colonizing uropathogens may also come from a sex partner’s vagina, rectum, or penis. Hematogenous seeding of the urinary tract by potential uropathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus is the source of some UTIs, but this is more likely to occur in the setting of persistent bloodstream infection or urinary tract obstruction. Many host behavioral, genetic, and biologic factors predispose healthy young women to uncomplicated UTI (Table 53-1). Risk factors include sexual intercourse, use of spermicide products, and a history of previous recurrent UTI.2,9 Nonsecretors of ABO blood group antigens are at increased risk for recurrent cystitis, the P1 blood group phenotype is a risk factor for recurrent pyelonephritis in women, and mutations in the gene for CXCR1, the interleukin-8 receptor, are more frequent and expression of CXCR1 is lower in children prone to pyelonephritis compared with controls.10 Factors protecting individuals from UTI include the host’s immune response; maintenance of normal vaginal flora, which protects against colonization with uropathogens; and removal of bladder bacteriuria by micturition.11 Uropathogenic E. coli, the predominant pathogens in uncomplicated UTI, are a specific subset of extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli that have the potential for enhanced virulence12 (Table 53-1). P-fimbriated strains of E. coli are associated with acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis, and their adherence properties may stimulate epithelial and other cells to produce proinflammatory factors that stimulate the inflammatory response. Other virulence determinants include adherence factors (type 1, S, and Dr fimbriae), toxins (hemolysin), aerobactin, and serum resistance. Bacterial virulence determinants associated with cystitis and asymptomatic bacteriuria have been less well characterized. Triggers for development of urinary symptoms are not entirely clear. Table 53-1 Factors modulating risk for acute uncomplicated urinary tract infections in women. Factors affecting the large difference in UTI prevalence between men and women include the greater distance between the usual source of uropathogens (anus and urethral meatus), the drier environment surrounding the male urethra, and the greater length of the male urethra. Risk factors associated with UTIs in healthy men include intercourse with an infected female partner, anal intercourse, and lack of circumcision, although these factors are often not present in men with UTI. Most uropathogenic strains infecting young men are highly virulent, suggesting that the urinary tract in healthy men is relatively resistant to infection. The initial steps leading to uncomplicated UTI discussed earlier probably also occur in most individuals who develop a complicated UTI. Factors that predispose individuals to complicated UTI generally do so by causing obstruction or stasis of urine flow, facilitating entry of uropathogens into the urinary tract by bypassing normal host defense mechanisms, providing a nidus for infection that is not readily treatable with antimicrobials, or compromising the host immune system (see Box 53-1).1 UTIs are more likely to become complicated in the setting of impaired host defense, as occurs with indwelling catheter use, VUR, obstruction, neutropenia, and immune deficiencies. Diabetes mellitus is associated with several syndromes of complicated UTI, including renal and perirenal abscess, emphysematous pyelonephritis and cystitis, papillary necrosis, and xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis.13 Uropathogen virulence determinants are less important in the pathogenesis of complicated UTIs compared with uncomplicated UTIs. However, infection with multidrug-resistant uropathogens is more likely with complicated UTI. Uncomplicated upper and lower UTI are most often caused by E. coli, present in 70% to 95%, and Staphylococcus saprophyticus, present in 5% to more than 20% (Table 53-2).1 S. saprophyticus only rarely causes acute pyelonephritis.14 Less common causes of uncomplicated UTI include other Enterobacteriaceae (e.g., Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella spp.) and rarely Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Citrobacter species (spp.), or other uropathogens. Among otherwise healthy nonpregnant women, the isolation of organisms such as lactobacilli, enterococci, group B streptococci, and coagulase-negative staphylococci other than S. saprophyticus most often represents contamination of the urine specimen.15 However, such organisms should be considered a likely causative agent in symptomatic women when found in voided midstream urine in high counts and pure growth. Table 53-2 Bacterial etiology of urinary tract infections. (Data for complicated infections from reference 1.) A broader range of bacteria can cause complicated UTI, and many are resistant to broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents. Although E. coli is the most common, Citrobacter spp., Enterobacter spp., P. aeruginosa, enterococci, and S. aureus account for a relatively higher proportion of cases compared with uncomplicated UTIs (Table 53-2).1 The proportion of infections caused by fungi, especially Candida species, is increasing (see Chapter 55). Patients with chronic conditions, such as spinal cord injury and neurogenic bladder, are more likely to have polymicrobial (multiorganism) and multidrug-resistant infections. Women with acute uncomplicated cystitis generally present with acute onset of dysuria, frequency, urgency, or suprapubic pain. Acute dysuria in a sexually active young woman is usually caused by acute cystitis; acute urethritis from Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, or herpes simplex virus infections; or vaginitis caused by Candida spp. or Trichomonas vaginalis.6 These three entities can usually be distinguished by the history, physical examination, and simple laboratory tests. Pyuria is present in almost all women with acute cystitis as well as in most women with urethritis caused by N. gonorrhoeae or C. trachomatis, and its absence strongly suggests an alternative diagnosis. Hematuria (microscopic or gross) is common in women with UTI but not in women with urethritis or vaginitis. Definitive diagnosis of UTI requires the presence of significant bacteriuria, the traditional standard for which is 105 or more uropathogens per milliliter of voided midstream urine. Studies have shown, however, that up to half of women with cystitis have lower colony counts, which are missed with use of the traditional definition. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) consensus definition of cystitis is 103 cfu/ml or more.16 Urine cultures are generally not indicated in women with uncomplicated cystitis, because the patient’s history has been shown to be highly reliable in establishing the diagnosis,17 the causative organisms are predictable, and the culture results usually become available only after therapeutic decisions have been made. E. coli in uncomplicated UTI is often resistant to sulfonamides and amoxicillin, and increasing resistance is also being observed for trimethoprim and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX, cotrimoxazole) in outpatient urinary strains in the United States and Europe.18,19 In the United States, cotrimoxazole resistance rates among E. coli strains causing uncomplicated UTI range from 15% to 42% in different regions,18 with a similar range among European countries and Brazil.19 Many drug-resistant E. coli organisms are clonal and have been hypothesized to enter new environments by contaminated products ingested by community residents.20 The prevalence of E. coli resistance to nitrofurantoin is generally less than 5%, although nitrofurantoin is inactive against Proteus spp. and some Enterobacter and Klebsiella spp. Fluoroquinolones remain active against most E. coli strains causing uncomplicated cystitis, although resistance is increasing in certain areas of the world.18,19 In a recent antimicrobial susceptibility study of more than 12 million E. coli isolates from U.S. outpatients, fluoroquinolone resistance increased from 3% to 17% over 10 years.21 In addition, infections caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)–producing strains are increasing in number, even in the setting of uncomplicated UTI. Recommended management of acute uncomplicated cystitis is summarized in Figure 53-1 and Table 53-3. Updated IDSA guidelines emphasize the importance of considering ecological adverse effects of antimicrobial agents (i.e., selection for colonization or infection with multidrug-resistant organisms—so-called “collateral damage”) when selecting a treatment regimen.22 Short-course regimens are recommended as first-line treatment for acute uncomplicated cystitis because of comparable efficacy, better compliance, lower cost, and fewer adverse effects than with longer regimens.23 Given the benign nature of uncomplicated cystitis along with its high frequency, the IDSA guidelines give equal weight to the risk of ecological adverse effects and drug effectiveness in the recommendations. Table 53-3 Oral antimicrobial agents for acute uncomplicated cystitis or cystitis in patients with possible occult renal or prostatic involvement. Nitrofurantoin is well tolerated and has good efficacy when given twice daily for 5 days, and it has a low propensity for ecological adverse effects.24 Despite concern about the high prevalence of resistance to TMP-SMX, this combination remains very effective and is inexpensive and well tolerated. Fosfomycin is also considered a first-line regimen because of its low propensity for ecological adverse effects, even though it appears to be clinically inferior to TMP-SMX and fluoroquinolones.22 Moreover, fosfomycin appears to have a role as a therapeutic agent effective against ESBL E. coli UTIs.25 The choice of an antimicrobial agent should be individualized based on the patient’s allergy and compliance history, local practice patterns, prevalence of resistance in the local community (if known), availability, cost, and patient and provider threshold for failure.22 If a first-line antimicrobial is not a good choice because of one or more of these factors, fluoroquinolones or β-lactams are reasonable alternatives, although it is preferable to minimize their use because of concerns about ecological adverse effects.22 Thus, although fluoroquinolones (3-day duration) are highly effective in the treatment of cystitis, many experts recommend that they be considered as second-line therapy for uncomplicated cystitis, to help preserve their usefulness in the treatment of other infections.22 In general, β-lactam antibiotics have been inferior to TMP-SMX or fluoroquinolones in regimens of the same duration.26 Although broad-spectrum oral β-lactams (e.g., cefixime, cefpodoxime, cefprozil, cefaclor, amoxicillin-clavulanate) demonstrate in vitro activity against most uropathogens causing uncomplicated cystitis, clinical data are sparse. Recent trials demonstrated that cure rates with 3-day regimens of amoxicillin-clavulanate27 or cefpodoxime proxetil28 were lower than a 3-day regimen of ciprofloxacin. Moreover, there are concerns about the possibility of ecological adverse effects with oral broad-spectrum cephalosporins, as has been observed with parenteral cephalosporins, although again few data exist. Given increasing antimicrobial resistance and the benign nature of cystitis, antimicrobial-sparing management strategies, such as the use of anti-inflammatory drugs (ibuprofen) or delayed treatment, neither of which is in common clinical use, are of increasing interest.15 Routine post-treatment cultures in women are not indicated unless the patient is symptomatic. If the patient remains symptomatic and has documented persistent infection, a longer course of therapy based on sensitivities, usually with a fluoroquinolone, should be used. The benefit of detecting and treating asymptomatic bacteriuria in healthy women has been demonstrated only in pregnancy and before urologic instrumentation or surgery.7,29 Most recurrent cystitis in healthy women is caused by repeated infection, which in many cases is caused by persistence of the initially infecting strain in the fecal flora.30 Experimental studies in mice also suggest that some same-strain recurrent UTIs may be caused by a latent reservoir of uropathogens in the bladder epithelium that persist after the initial UTI,31 and indirect evidence indicates that this pathogenesis pathway may occur in humans.32 If the recurrence is within 1 or 2 weeks of treatment, an antimicrobial-resistant uropathogen should be considered, and a urine culture should be performed followed by treatment with an alternative regimen. It is reasonable to treat later recurrences the same as the original infection, although if TMP-SMX has been used in the previous 6 months, an alternative drug should be considered.15 The goal of long-term management of recurrent cystitis should be to improve the quality of life while minimizing antimicrobial exposure.15 Women with recurrent cystitis may benefit from behavioral modification (Fig. 53-2), such as avoiding spermicides, increasing fluid intake, and ensuring postcoital micturition, although the benefit of these practices has not been proved. Although ingestion of cranberry products has been thought to have preventive properties based on small clinical studies and in vitro inhibition of uropathogen adherence to uroepithelial cells, a recent randomized, placebo-controlled trial (RCT) showed no benefit from cranberry juice.33 Women who do not want to try or who obtain no benefit from the preceding approaches should be offered antimicrobial prophylaxis.

Bacterial Urinary Tract Infections

Definition

Epidemiology

Pathogenesis

Uncomplicated Infection

Factors Modulating Risk for Acute Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections in Women

Host Determinants

Uropathogen Determinants

Behavioral: sexual intercourse, use of spermicidal products, recent antimicrobial use, suboptimal voiding habits

Escherichia coli virulence determinants: P, S, Dr, and type 1 fimbriae; hemolysin; aerobactin; serum resistance

Genetic: innate and adaptive immune response, enhanced epithelial cell adherence, antibacterial factors in urine and bladder mucosa, nonsecretor of ABO blood group antigens, P1 blood group phenotype, reduced CXCR1 expression, previous history of recurrent cystitis

Biologic: estrogen deficiency in postmenopausal women, glycosuria (including from SGLT-1 inhibitors)

Complicated Infection

Etiologic Agents

Bacterial Etiology of Urinary Tract Infections

Organisms

Urinary Tract Infection (%)

Uncomplicated

Complicated

Gram-Negative Organisms

Escherichia coli

70-95

21-54

Proteus mirabilis

1-2

1-10

Klebsiella spp.

1-2

2-17

Citrobacter spp.

<1

5

Enterobacter spp.

<1

2-10

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

<1

2-19

Other

<1

6-20

Gram-Positive Organisms

Coagulase-negative staphylococci (Staphylococcus saprophyticus)

5-20 or more

1-4

Enterococci

1-2

1-23

Group B streptococci

<1

1-4

Staphylococcus aureus

<1

1-2

Other

<1

2

Clinical Syndromes

Acute Uncomplicated Cystitis in Young Women

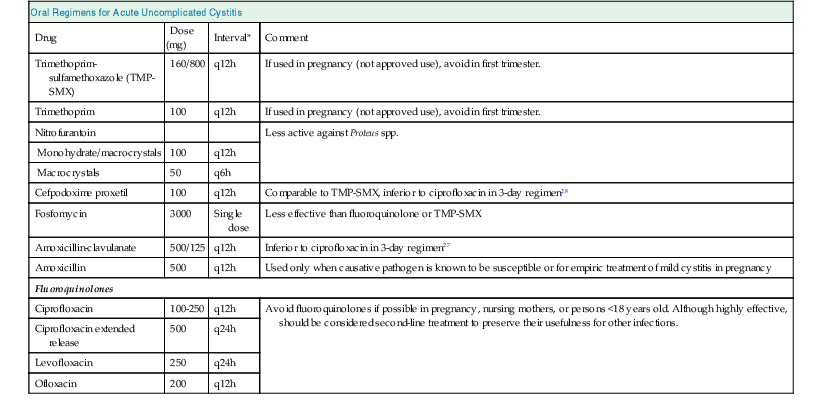

Oral Regimens for Acute Uncomplicated Cystitis

Drug

Dose (mg)

Interval*

Comment

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX)

160/800

q12h

If used in pregnancy (not approved use), avoid in first trimester.

Trimethoprim

100

q12h

If used in pregnancy (not approved use), avoid in first trimester.

Nitrofurantoin

Less active against Proteus spp.

Monohydrate/macrocrystals

100

q12h

Macrocrystals

50

q6h

Cefpodoxime proxetil

100

q12h

Comparable to TMP-SMX, inferior to ciprofloxacin in 3-day regimen28

Fosfomycin

3000

Single dose

Less effective than fluoroquinolone or TMP-SMX

Amoxicillin-clavulanate

500/125

q12h

Inferior to ciprofloxacin in 3-day regimen27

Amoxicillin

500

q12h

Used only when causative pathogen is known to be susceptible or for empiric treatment of mild cystitis in pregnancy

Fluoroquinolones

Ciprofloxacin

100-250

q12h

Avoid fluoroquinolones if possible in pregnancy, nursing mothers, or persons <18 years old. Although highly effective, should be considered second-line treatment to preserve their usefulness for other infections.

Ciprofloxacin extended release

500

q24h

Levofloxacin

250

q24h

Ofloxacin

200

q12h

Recurrent Acute Uncomplicated Cystitis in Women

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Bacterial Urinary Tract Infections

Chapter 53