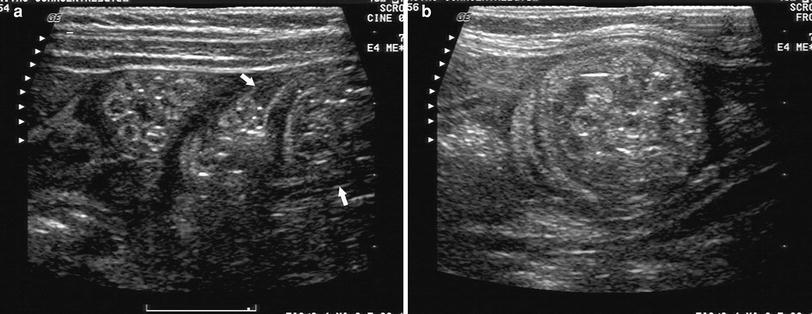

Fig. 1

a Longitudinal and b transverse scans of right iliac fossa showing asymmetric thickening of walls of the caecum, suggestive of amoeboma in a patient with amoebic liver abscess. c Non-tender thickening of appendix (A) in amoebiasis. Cecal walls are also slightly thickened (CE)

2 Ascariasis

Ascariasis is the infestation of the humans with the round worm, Ascaris Lumbricoides. The adult worms normally live in the lumen of the small bowel of an infected individual. The eggs of the worm are passed in the faeces of these individuals and can contaminate water or food. Humans become infected when they ingest contaminated water or food. Gastric juices cause the eggs to hatch in the small bowel. The larvae penetrate the intestinal wall to enter the blood stream and reach the lungs. They migrate, or are carried by the bronchioles to bronchi, ascend the trachea to the glottis and pass down the oesophagus to the small intestine (Neva and Brown 1994). Ascariasis is worldwide in distribution and is more common in warm countries and is most prevalent where sanitation is poor. It occurs at all ages, but it is most prevalent in children aged 5–9 years. The incidence is approximately the same in both sexes. The usual infection consists of 5–10 worms and often goes unnoticed by the host. The most frequent complaint of patients with ascariasis is vague abdominal pain. When the infestation is heavy, a bolus of worms may cause serious complications such as intestinal obstruction (Malde and Chadha 1993; Wasadikar and Kulkarni 1997; Mahmood et al. 2001), perforation (Hangloo et al. 1990; Chawla et al. 2003), intussusception (Villamizar et al. 1996) or volvulus (Rodriguez et al. 2003). The prognosis of these complications depends on prompt diagnosis and treatment. Delay in diagnosis may give rise to small bowel gangrene. Clinical findings in such cases are those of the complications, which are acute pain in the abdomen, vomiting or signs of peritonitis.

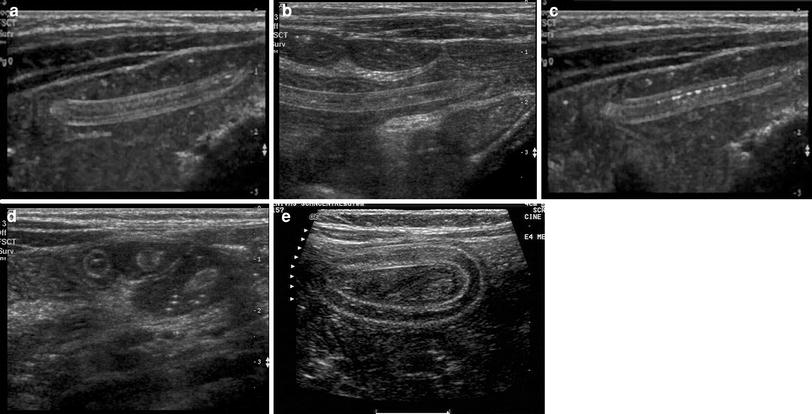

On sonography, the appearance of the round worms varies with the frequency of transducer used. When the recent high-resolution probes are used, the ascaris worm is seen as a chord of four echogenic lines in longitudinal scans (Fig. 2a, b). These lines represent the reflections from the external walls of the worm and the walls of alimentary tract of the worm (Mahmood et al. 2001). Sometimes the alimentary canal appears echogenic when it is filled with air (Fig. 2c). In cross-section it appears like a small doughnut (Fig. 2d). It is clearly visible if there is fluid around the worm. On low-frequency scans, it is seen as two parallel lines on longitudinal scan (Fig. 2e) and a circle on transverse scan. On real-time scan, the worm shows non-directed curling movement.

Fig. 2

Sonographic appearance of the ascaris worm. Longitudinal scan of the worm showing the 4-line appearance in (a), hypoechoic fluid-filled alimentary tract of the worm in (b) and air-filled echogenic alimentary tract in (c). d Transverse scan of multiple worms showing the small doughnut appearance. e On low-frequency scan the worm is seen as two parallel lines

In the presence of small bowel obstruction due to a ball of worms, sonography shows signs of small bowel obstruction, namely, dilated small bowel loops with peristalsis. At the site of obstruction the ball of worms, or helminthoma, appears like spaghetti on longitudinal scan (Fig. 3a) and a “shack of cigars” on transverse scan (Fig. 3b; Malde and Chadha 1993; Wasadikar and Kulkarni 1997). Sonography is useful in the follow-up of these patients after initiating the treatment. It can reveal resolution of the obstruction or occurrence of other complications, such as volvulus or ischaemia of the bowel. In volvulus and ischaemia of the small bowel due to ascariasis, sonography shows multiple loops of unusually dilated, aperistaltic small bowel, containing the ascaris worms with the classical appearance and movement. There is free fluid in the peritoneal cavity. The walls of the bowel are thickened (Rodriguez et al. 2003). Perforation of the bowel due to ascariasis can very occasionally occur because of direct pressure and irritation of the bowel wall by impacted ascaridial masses, leading to ulceration, necrosis and perforation. Lytic secretion from ascarides probably also plays a role (Hangloo et al. 1990). In perforation, sonography reveals live ascaris worms moving freely within the extraluminal fluid (Chawla et al. 2003). Very rarely, ascariasis worm can enter the appendix and cause appendicitis (Misra et al. 1999).