12

Arthritis in Aging Men

Case History

Mr. L.C. is a 75-year-old man who presented to the Geriatrics Evaluation and Management Clinic after being referred by his primary care physician. His main complaint was that he was not able to cope at home. His wife died 6 months ago, and he confesses to being sad. His main concern was that his mobility was limited partly because of “weakness of his knees.” He said that he is unable to walk because of pain and that he was dependent on a walker. His past medical history included insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and osteoarthritis. He was also recently diagnosed by his primary physician to have rheumatoid arthritis (RA) of his left knee after he presented with knee swelling and had synovial fluid aspirated. Physical examination revealed a frail gentleman, weighing 187 pounds. His blood pressure was 176/86mm Hg and cardiopulmonary examination was normal. He had clinical suggestion of hypogonadism because of loss of axillary hair and testicular atrophy. Muscle strength in the lower extremities was 4/5 bilaterally and reflexes were diminished. There was a mild degree of genu varus of the knee, but the right knee was noticeably swollen and felt doughy. There was presence of Heberden’s nodes in both hands, but his metacarpophalangeal joints were normal. His Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination was 27/30, suggesting some degree of cognitive impairment. His Geriatric Depression Score was 3/15, suggesting that he was not clinically depressed at this stage. Blood work revealed that his blood chemistry, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) were within normal range. Of note was the hemoglobin at 11.5g/dL, positive rheumatoid factor, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 66mm/hour, total testosterone 190ng/dL (low), free testosterone 24.4ng/dL (low), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) 9.6mIU/mL (elevated), and HbA1c 8 (elevated).

To summarize, Mr. L.C. was diagnosed to have a fall risk from arthritis and muscle wasting. In addition, he has suggestions of early dementia but was not clinically depressed. The rise in FSH is consistent with Leydig cell failure, leading to andropause. He needed better control of his blood pressure and diabetes. Incidentally too, he was hypogonadal as evidenced by examination and laboratory testing. The treatment plan included increasing the dose of his antihypertensive and diabetic medications. He was given testosterone for his hypogonadal state. His arthritis medications were unchanged.

Arthritic Problems in Aging Men

“Arthritis” can mean more than a hundred different diseases with different etiologies, manifestations, and prognoses. Further, arthritis has always been associated with aging. We have heard our parents and grandparents complain of pain, and relate it to their age. However, the aging process does not imply the presence of arthritis. There are physiological changes in bone, joint, and muscle related to age, but none of those cause symptoms that can be diagnosed as arthritis. Nevertheless, the prevalence of the different types of arthritis in general increases with age, making this group of diseases the leading cause of disability in the elderly.1,2

The elderly man can be affected by any of the different diseases we know as “arthritis.” From osteoarthritis, the most common type, to systemic lupus erythematosus, all can cause morbidity in this population group. This chapter discusses aspects of rheumatology that affect aging men such as osteoarthritis, RA, and polymyalgia rheumatica/giant cell arteritis. Ankylosing spondylitis and other spondyloarthropathies and collagen vascular diseases are also discussed.

FIGURE 12-1. Prevalence of significant hip pain on most days in older adults, stratified by age and sex. Osteoarthritis and symptoms are reported more frequently in females. (Adapted from Christmas C, Crespo CJ, Franckowiak SC, et al. How common is hip pain among older adults? Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Fam Pract 2002;51(4), with permission.)

Osteoarthritis is the most common of the diseases of the joints.3,4 It affects a large percentage of the population causing significant disability.5 Its incidence and prevalence increases progressively with age, with persons being affected starting at variable age depending on the cause of the disease. Fig. 12–1 shows the rates of reporting of hip pain in both men and women. Osteoarthritis is not a normal consequence of aging. Actually, the changes noted in aging cartilage are in many ways the opposite of the changes noted in osteoarthritic cartilage.4,6 For example, the aging cartilage has a decrease in the amount of fluid and the number of chondrocytes, and an increase in the amount of collagen and in hyaluronate content. Osteoarthritic cartilage has an increase of the amount of fluid, due to the fibrillation of the surfaces, changes in the amount in hyaluronate, and an initial increase in the amount of chondrocytes to try and repair the damage. Eventually the cartilage cannot repair itself anymore, and a loss of volume occurs.

The etiology of osteoarthritis is unclear.4,6 Theories suggest the presence of poor cartilage submitted to normal stress, the presence of normal cartilage submitted to excessive stress, or a combination of both. The poor-cartilage theory explains the nodular osteoarthritis of the hands, which is clearly inherited, affecting mostly females, and the osteoarthritis associated with diseases like hemochromatosis or hypothyroidism. The excessive stress theory explains the osteoarthritis seen after direct joint trauma, the one noted in persons in specific occupations or in overweight individuals. However, primary osteoarthritis cannot be in many cases clearly explained by one of the mechanisms, and is probably a combination of both. Osteoarthritis affects more females than males,7 and it is probably due to the predominance of estrogen receptors in the bone and cartilage cells that modify the rate of metabolism.8

Osteoarthritis affects a large percentage of the population.9 It usually manifests with pain that occurs with activity. With time, pain occurs with less activity and eventually starts to bother the individual at rest. Patients usually feel a short-lived sensation of stiffness in the joints, like the joints are “glued together,” that lasts less than half an hour. Joint inflammation is usually not a component of the disease. However, “flares” may occur that can cause synovial fluid accumulation and effusions. These are commonly present after episodes of overactivity. Some patients may have calcium deposits in the cartilages, causing chondrocalcinosis. These patients are exposed to acute joint swelling episodes and are diagnosed with pseudo-gout. Primary osteoarthritis affects knees, hips, and digits, mostly at the distal interphalangeal joints. Secondary osteoarthritis may affect other joints, which may help to diagnose the origin of the disease.10 For example, involvement of the metacarpophalangeal joints suggests the presence of hemochromatosis, or damage to wrists suggests the presence of chondrocalcinosis. Heberden and Bouchard nodules are typical of osteoarthritis of the hands, and are significantly more common in females. These changes are usually familial in origin.

Regrettably we still do not have a specific treatment for osteoarthritis. However, that does not mean that there is not much to do, as many patients are told. There are many ways to keep patients with osteoarthritis from suffering, and perhaps, to slow down the progression of disease.11–13 The initial part of the therapy is education. Many patients feel that the disease is not treatable and that they will be disabled in a short time. That is not the case for most patients. An exercise program, directed to muscle strengthening and range of motion decreases pain in many cases by decreasing the load inside the joint, and improves results in case the patient eventually requires surgery. Use of a cane and weight reduction in patients who are overweight also decrease load and slow progression of disease. For patients with mild pain, the use of analgesics like acetaminophen may be enough. However, when pain becomes more severe, use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is recommended. Both the American College of Rheumatology and the American Pain Society recommend the use of Cox-2-specific medications in this setting, because the elderly are at significant risk of gastrointestinal complications or nonspecific ones.14 Use of a proton pump inhibitor or misoprostol with nonspecific NSAIDs are other options.

Local steroid injections are indicated for patients with “flares” or patients who have pseudogout episodes. However, repeated use of the intraarticular steroids may accelerate the progression of disease. When effusions are present, the muscles around a joint will be inhibited, causing significant loss of strength and muscle atrophy. Therefore, effusion should in general be drained. Hyaluronic acid derivatives have been approved for the use in osteoarthritis of the knee.15 It is not clear what the mechanism of action is, but patients may have long-lasting pain control after the series of injections. These are usually prescribed for patients who cannot or will not take antiinflammatory medications, or for patients who still have pain with adequate medication use.

Chondroprotective medications, drugs that can improve or protect the cartilage from further damage, have been under investigation for a long time. Glucosamine sulfate, an over-the-counter product, suggests in limited studies a chondroprotective effect.16 Doxycycline has also been found to have some chondroprotective effect in vitro, but clinical studies have not been conclusive.

When pain does not respond to nonpharmacological and pharmacological treatment or when deformity is progressive, patients are considered surgical candidates. Techniques have evolved significantly, and unicompartmental procedures are becoming more frequent. Total replacements of the knee and the hip have become common practice and have in general excellent results. Arthroscopic procedures are indicated in patients that have mechanical derangements in the joints, but have not been very helpful for patients with only osteoarthritic changes. Osteoarthritis will continue to be a major public health problem with the graying of our society. We are far from a cure, but adequate treatment will decrease significantly morbidity in our patients.

Rheumatoid arthritis is the most common of the inflammatory arthritides. It affects about 1% of the general population. However, its distribution varies depending on sex and age. It is more common in females and increases progressively with age. If untreated, it can cause significant disability and increased mortality. Seropositive RA, the disease that has a positive rheumatoid factor (∼80% of patients), has not such a significant female preponderance. There is an unsolved question about the difference between RA presenting early in life and late-onset RA. Initial studies suggested that the elderly had a lower incidence of rheumatoid factor and that the disease seemed to be milder. However, later studies indicate that the disease seems to be as aggressive in the elderly population as in the younger one, requiring a similar approach to diagnosis and therapy.17

The cause of RA is not known. There is a genetic predisposition to the disease related to the presence of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR4 or similar histocompatibility antigens. Theories have included infections with different viruses, like the Epstein-Barr virus, or bacteria, like mycoplasma or other intracellular organisms. These have been found by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in joints of affected individuals. However, whatever the cause, it seems to be only a trigger for a faulty immunological response that arms a cell-mediated attack to the synovium and other tissues. The cytokine balance is abnormal in patients with RA, presenting increased amount of tumor necrosis factored and other cytokines with decrease of interferon-γ and other cytokines. Regardless of the origin, the inflammatory infiltrate in the joint creates significant synovial growth and erosion of the bone. If left unchecked, that disorderly growth can destroy the cartilage and the periarticular bone, causing complete joint destruction and in some cases ankylosis.18 RA is a systemic disease that may affect other organs like the pleura, the pericardium, the heart, and blood vessels. Large effusions may be the presenting characteristic of the disease, and nodules may affect the heart rhythm. Systemic vasculitis and leucopenia with splenomegaly (Felty’s syndrome) are very serious complications of the extraarticular disease.

Rheumatoid arthritis usually presents with slowly progressive symptoms that become more prevalent over the course of months.19 Patients initially feel frequent tiredness and morning stiffness, usually associated with inflammatory changes in the joints of the hands and occasionally the feet. With time the pain and stiffness affects other joints, including shoulders, elbows, knees, ankles, and hips. Temporomandibular and neck joints are affected later, and the thoracic and lumbar spine are rarely affected. A minority of patients may present with an explosive onset of disease, or with an affection of only one or two joints. There is a belief among many rheumatologists that the disease tends to start more acutely in the elderly. However, it is difficult sometimes to differentiate polymyalgia rheumatica, which usually has an acute onset, from RA. Extraarticular manifestations are rare early in the disease, but large pleural effusions may be the heralds of RA.

The treatment of RA has changed significantly in the last 10 years, and especially in the last 3 or 4. By the last decade of the twentieth century it was clear that RA caused not only very significant morbidity, with loss of income and independence for the affected individuals, but also a significant increase in mortality. Also it was noted that damage to the joints occurred early in the disease, and that most of the impact of the disease took place within 3 years of diagnosis.20 Therefore, it was important to treat the disease early and aggressively to avoid that initial joint damage. It was clear that NSAIDs, although they decreased pain and somewhat decreased inflammation, did not change the progression of disease. The pyramid of treatment, which allowed for initial nonpharmacological treatment, then use of NSAIDs, and then the slow introduction of drugs considered at that time modifiers of disease (gold salts, penicillamine), was abandoned. The introduction of methotrexate gave rheumatologists a drug that was easier to use and that improved significantly the joint inflammation.21,22 Combination therapy with hydroxychloroquine and sulfasalazine and the use of low-dose steroid therapy were later introduced for patients who did not respond adequately to methotrexate.23 Some rheumatologists, following the lead of oncologists, decided to use a very aggressive “remission” treatment with combination therapy at the beginning of disease.24 Leflunomide was a new option for treatment to replace methotrexate, or to complement treatment of patients who failed methotrexate.25 The introduction of the biologicals, tumor necrosis factor-a inhibitors (etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab), and interleukin-1 inhibitors (anakinra), was a revolution in the treatment of the disease.26

At this time the treatment of RA should be considered an emergency. It can be parallel to the treatment of hypertension or hyperlipidemia. The goal is to control the disease before it can cause any significant anatomical damage or any major disability. There has been a question of whether the treatment in the elderly should be different, but studies suggest that the impact of the disease is similar in all age groups and all should be treated aggressively.27 Therefore, when a diagnosis of RA is made, treatment should be started with a disease-modifying agent. Because so many are available, with different toxicity and activity profiles, a rheumatologist or a physician with experience in the use of these medications should be consulted. The prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis has decreased in our society, but the disease still causes significant morbidity and increases mortality. New discoveries have revolutionized treatment, and although we still are far from knowing the specific cause of the disease, we can now improve the quality of life and slow or stop the progression of disease in many, if not most, patients.

Polymyalgia rheumatica is a disease that causes significant morbidity in the elderly. Its causes are not known. Theories, similar to those of RA, have included viral and bacterial infections. It affects only the elderly, being extremely rare before age 55. It has a significant predominance in females over males. However, most affected females are postmenopausal, making a hormonal cause unlikely. There are no adequate pathology reports because the disease is usually self-limited and does not cause any deformity. The disease is clearly inflammatory, because its hallmark is elevation of the sedimentation rate. Whole-body bone scan has shown increased uptake in the shoulders and hips. The disease presents acutely—the patient usually goes to sleep feeling well and wakes up with very severe stiffness that affects mostly the shoulders and the hips. Some patients have such severe disease that they may not be able to get out of bed without help. Low-grade temperature, loss of appetite, general malaise, and loss of weight are frequent symptoms.28 Some patients may respond to treatment with NSAIDs, but most of them will require a low dose of glucocorticoids. The disease is frequently self-limited, but may last 1 year or longer. Therefore, patients require usually long-term glucocorticoids.29 These patients should be educated about the risks of the medications, and required bone density tests and osteoporosis prophylaxis with calcium, vitamin D, and a diphosphonate.

Temporal arteritis or giant cell arteritis is a disease that is usually associated with polymyalgia rheumatica. It is unknown if those two diseases are different manifestations of the same pathological process or two independent entities that have similar trigger mechanisms. Giant cell arteritis affects mostly elderly women, though not exclusively. It presents mostly in patients who have symptoms of polymyalgia rheumatica. It causes inflammatory changes in the walls of the branches of the carotid arteries or the ascending aorta. It affects mostly the extracranial vessels.30 It is a very inflammatory disease causing frequently fever, malaise, weight loss, and extreme fatigue. Patients present with severe headache, usually located in the temporal areas, and with claudication of the areas irrigated by the extracranial branches of the ascending aorta, especially the temporal muscles. The most dreaded consequence of the disease is blindness. It is initially unilateral, but if not treated, can rapidly affect the contralateral side. Diagnosis of temporal arteritis can be difficult. It should be suspected in patients with polymyalgia rheumatica who present also with headaches or jaw claudication. However, if it does not present in the company of polymyalgia rheumatica, it can be confused with migraines, cardiovascular complications, or cerebrovascular incidents, with awful results. In some cases a fever of unknown origin in an elderly individual may be the only manifestation of temporal arteritis. The sedimentation rate and the C-reactive protein (CRP) are usually elevated, which helps in making the diagnosis. When the disease is suspected, treatment with high-dose glucocorticoids should be started without waiting for a pathology report. However, the only way to confirm the diagnosis is by temporal artery biopsy. In general, the surgeon should obtain a long segment, and be ready to do a bilateral procedure if the preliminary report is negative. The treatment is with high-dose glucocorticoids, for example, 60 to 80 mg of prednisone in divided doses. The dose is decreased slowly during the next few months, and most patients need treatment for at least 1 year.

Ankylosing spondylitis is an inflammatory disease that affects mostly men in the third and fourth decades of life. It presents in about 0.5% of the general population. Its etiology is not clearly known, but most patients with the disease present with histocompatibility antigen HLA-B27 or a similar one.31 The prevalence of the disease in a population parallels the frequency of that antigen in the same group. It seems to be triggered by an infectious agent, and Shigella, Salmonella, and Chlamydia have been blamed. The disease starts with alternating pain and stiffness in the gluteal area that slowly ascends through the spine, causing significant pain and limitation of range of motion. If the disease is not treated, patients may lose range of motion of the spine, and of the large peripheral joints. The disease is frequently associated with uveitis, fibrotic lung changes, and nonrheumatic aortic insufficiency. Fig. 12–2 depicts a patient with uveitis, which is often associated with ankylosing spondylitis. Elderly patients usually have had the disease for a long time, resulting in significant limitations. The disability caused by the disease can be severe. However, even after this long disease duration, it may remain active, and many patients require aggressive treatment to preserve use of peripheral joints like the hips or knees.

FIGURE 12-2. Anterior uveitis commonly associated with ankylosing spondylitis.

The diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis is clinical. There are sets of criteria for diagnosis, including the New York32 and the European33 sets. These criteria are important for clinical research, but in clinical settings a more empirical approach is required. Patients have the previously indicated symptoms and x-rays or bone scan suggesting inflammation of the sacroiliac joints. Computed tomography (CT) scan is very sensitive, but its cost is generally not justified. The use of HLA-B27 as a diagnostic test is not recommended in general because the prevalence of that gene in the general population is significantly higher than the one for the disease. In the elderly the diagnosis is usually easy because the disease has progressed for many years and patients present with significant loss of range of motion of the lumbar spine in all planes. X-rays show syndesmophytes and in many cases complete obliteration of the sacroiliac joints.

Treatment of the disease has changed significantly. Until recently the NSAIDs, and especially older drugs like indomethacin, were the only accepted treatment. Sulfasalazine and methotrexate have been used in doses similar to the ones used in RA with mixed results.34,35 The introduction of the tumor necrosis factor-a inhibitors has made a big difference for these patients.36 The inflammatory component of the disease responds very well, preventing in many cases progression of disease. In the elderly, the treatment should remain aggressive if the disease is active and the patient has severe pain, or progression can impact activities of daily life. These patients may need a combined approach that may include aggressive rehabilitation and in many instances surgery. Therefore, these patients benefit from a referral to a rheumatologist or to a physician with experience in the management of these diseases.

Collagen-vascular diseases are a group of systemic autoimmune diseases that include systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren’s syndrome, polymyositis/dermatomyositis, and scleroderma; there are overlaps between these diseases.37 The etiology of these diseases is unknown, but all share the presence of autoantibodies directed to the nucleus of the cell. They have similar genetic predisposition. The target of the inflammatory response and the symptoms help us differentiate among them. They are diseases more commonly diagnosed in females, and in younger groups. However, new onset of these diseases has been described in all ages and all sexes. Therefore, an elderly man who presents with fever, sun-sensitive rash, arthralgia and arthritis, and a positive antinuclear antibody will have lupus, and will require an aggressive approach to diagnosis of affected major organs, and treatment depending on the findings.38 Lupus in the elderly tends to be a less aggressive disease, with less glomerular compromise. However, treatment of lupus should be similar in all age groups and should be directed at the seriousness of the disease. Once again, the use of glucocorticosteroids has higher risks, especially for osteoporosis and worsening of arteriosclerotic lesions.

Dermatomyositis differs from the other autoimmune diseases. It has a significant association with malignancy. Therefore, patients who present with this disease should undergo an extensive evaluation. The disease, however, is not a paraneoplastic syndrome, and it progresses independently of the malignancy. Diagnosis of polymyositis/dermatomyositis is made in patients who present with significant muscle weakness and elevated muscle enzymes. Electrophysiological studies and muscle biopsy are important to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other myopathies. This is more important in the younger population that may have muscle dystrophies.

Scleroderma is usually advanced when seen in the elderly. In those cases making the diagnosis is easy, if it has not been made earlier. However, the treatment options are more limited, and are directed more to the complications of the disease, such as lung fibrosis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, esophageal stenosis, loss of digits, and chronic extremity pain.

Sjogren’s syndrome is more frequent in postmenopausal women and is rare in men. However, it can cause fever of unknown origin, blindness, oral abnormalities, rashes, lymphadenopathy, and other symptoms that can be difficult to classify. Suspicion of Sjogren’s syndrome can help explain many mystery diseases in the elderly.39

A comment is necessary on fibromyalgia.40 Again, it is a disease more frequent in women. Many men have chronic pain, but have never been evaluated or treated for the disease. It has no specific diagnostic test. Patients present with morning stiffness, easy fatigability, and pain in areas around the joints. A diagnosis of RA is usually considered, but because no swelling is noted and the rheumatoid factor and the acute reactants are negative, it is ruled out. On examination, the presence of tenderness in the fibromyalgia points is noted. It is important to make this diagnosis, because this disease is usually not progressive. Patients can be reassured, and treated with low-dose tricyclic antidepressants. An exercise program can yield great improvement. New medications are being introduced to treat pain specifically in fibromyalgia.

Rheumatoid Arthritis and Relationship to Androgens

Rheumatological diseases are less common in men than in women. It has been argued that this may be because of the protective effect of androgens, as men have a substantial larger amount of testosterone as compared with women. Indeed, women have only ∼10% of the testosterone that men have. This may be a simplistic view; but studies in both men and women have found that there is association of low testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) with rheumatoid disease. For example, in a study at Karolinska Institute in Sweden, it was found that men with RA had lower levels of bioavailable testosterone, and a large proportion were considered hypogonadal. The low levels of luteinizing hormone (LH) suggested a central origin of the relative hypoan-drogenicity.41 In this study basal serum concentrations of total testosterone (T), sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), and LH were measured in 104 men with RA, and the quotient T/SHBG were calculated. The data were compared with those of 99 age-matched healthy men. The results were analyzed separately for the age groups 30 to 49, 50 to 59, and 60 to 69 years. The RA men had lower biovailable testosterone levels than the healthy men in all age groups. Testosterone levels and the T/SHBG ratio were lower only in the 50 to 59 age group, but SHBG did not differ significantly. LH was significantly lower in the patients than in the controls. Thirty-three of the 104 patients were considered to have hypogonadism compared with 7 of the 99 healthy men. The only clinical variable apart from age that had a significant impact on biovailable testosterone was the Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) score.

Biological Role of Androgens in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Molecular Basis for Testosterone Adjuvant Therapy

It is generally believed that androgens exert antiinflammatory properties, whereas estrogens are immunoenhancing.42 Certain chemicals found in the environment, such as those in plastics, pesticides, plants, and agricultural products mimic estrogens or “phytoestrogens” and can also block androgen action. Exposure to these antiandrogens may cause changes similar to those associated with estrogen exposure.43 To exert direct immunoregulatory effects, neurohormones and steroid hormones need to diffuse passively into target cells, interact with intracellular receptors, and then be translocated into the genome. Human and murine macrophages exhibit functional cytoplasmic and nuclear androgen and estrogen receptors. They can also metabolize gonadal and adrenal androgen precursors [testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS)] into their active metabolites [dihydrotestosterone (DHT) and DHEA]. As such, chronic inflammation such as in RA may lead to a hypogonadal state. In addition, studies of the effects of intraarticular testosterone and DHT on cartilage breakdown and inflammation in animal models of RA indicate significant inhibitory activity of these steroids on synovial hyperplasia and cartilage erosion.44 In a laboratory experiment by Steward, testosterone and its metabolite 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT) were compared with dexamethasone 21-acetate in two different animal models of arthritis. The researchers found interesting effects on cartilage breakdown and inflammation. In the mouse air pouch, at the three dose levels used, significant effects were obtained with DHT and were more pronounced on cartilage breakdown than on inflammation. Even at low doses, there was a 64% inhibition of collagen breakdown and 18% inhibition of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) breakdown with androgens. In the antigen-induced arthritis mouse model, testosterone had significant inhibitory effects on synovial hyperplasia and cartilage erosion.45

Genetic polymorphism may also contribute to RA etiology by endocrine interactions. For example, the estrogen synthase (CYP19) locus is the cytochrome p450 that catalyzes the conversion of C19 androgens to C18 estrogens. In RA, a linkage to this locus has been described in sibling pair families having an older age at onset of the disease. CYP19 polymorphisms that lead to higher levels of CYP19 or higher enzyme activity lead to reduced levels of androgens and hence may put an older individual at risk for RA.46 The rise in incidence in RA with age is associated with a decline in androgen production declines in both older males and females.

Stress may influence neuroendocrine and immune mechanisms adversely resulting in a reduction of testosterone production. A subgroup of RA patients who were found to have high stress at onset of the disease showed a worse disease prognosis.47 Even minor life events might precipitate further RA flares. Studies have shown a greater occurrence of increased disease activity, joint tenderness, and pain in RA even with minor stress.

Clinical Trials of Testosterone in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis

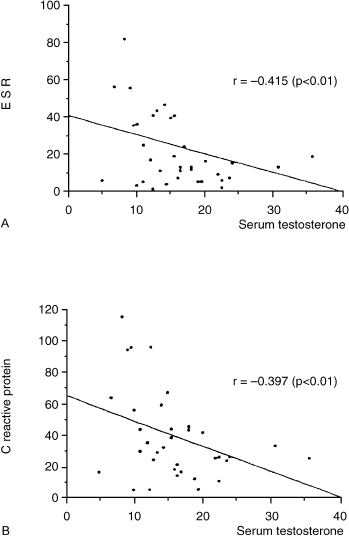

In clinical practice, patients placed on testosterone therapy for hypogonadism-related symptoms, such as loss of libido, report a surprising improvement in their pain threshold from their associated arthritis. However, the few prospective trials of the use of testosterone as an adjuvant have been equivocal. For instance, in Hall et al’s481996 trial reported in the British Journal of Rheumatology, there was no suggestion of a positive effect of testosterone on disease activity in men with RA (Fig. 12–3). In that study, 35 men, aged 34 to 79 years, with definite RA were recruited from outpatient clinics and randomized to receive monthly injections of testosterone enanthate 250 mg or placebo as an adjunct therapy for 9 months. End points included disease activity parameters and bone mineral density (BMD). At baseline, there were negative correlations between the ESR and serum testosterone (r = –0.42, p < .01) and BMD (hip, r = –0.65, p < .01). Thirty patients completed the trial, 15 receiving testosterone and 15 receiving placebo. There were significant rises in serum testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, and estradiol in the treatment group. There was no significant effect of treatment on disease activity overall, and five patients receiving testosterone underwent a “flare.” Differences in mean BMD following testosterone or placebo were nonsignificant.

FIGURE 12-3. Relationship between inflammatory markers such as (A) erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and (B) C-reactive protein (CRP) with serum testosterone levels. The lower the testosterone levels, the higher the marker of inflammation. (Adapted from Hall GM, Larbre JP, Spector TD, et al. A randomized trial of testosterone therapy in males with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 1996;35: 568–573, with permission.)

In another study from Italy, however, Cutolo and his group49 seemed to have proved that testosterone was useful in those men with active RA. In that trial seven men were treated daily for 6 months with oral testosterone undecanoate plus an NSAID in an attempt to evaluate the immunological response, the overall clinical response, and the sex hormone response to such replacement therapy. At the end of the 6 months, there was a significant increase in serum testosterone levels (p<.05), an increase in the number of CD8+ T cells, and a decrease in the CD4+:CD8+ T-cell ratio. The immunoglobulin M (IgM) rheumatoid factor concentration decreased significantly (p <.05). There was a concurrent significant reduction in the number of affected joints (p <.05) and in the daily intake of NSAIDs (p <.05). The authors report that the immunosuppressive action of androgens probably contributed to the findings in these RA patients.

In our opinion, both these trials are limited by sample size, and hence testosterone’s role in RA remains to be determined. The negative result of the first trial could be the result of an inadequate dosing of testosterone at 250mg monthly. In contrast, the positive result of the second trial was achieved because of a daily dosing of testosterone undecanoate, which resulted in eugonadal levels. It was interesting that NSAID usage was decreased in the second trial. This is significant especially for patients who are at risk for peptic ulcer disease. In a separate study, Martens and his colleagues50 reported that men with RA who are not taking prednisone have significantly elevated levels of FSH and LH with normal testosterone levels, suggesting a state of compensated partial gonadal failure. However, men with RA taking low doses of prednisone have lower testosterone and gonadotropin levels, suggesting that prednisone may suppress the hypothalmic-pituitary-testicular axis. Because testosterone affects immune function as well as bone and muscle metabolism, androgen deficiency in some men with RA may predispose them to more severe disease and to increased complications of steroid therapy such as myopathy and osteoporosis. Overall, there exists an interesting interplay of androgens with RA, but the relationship may be multifactorial. As such, there is no blanket recommendation to use adjuvant testosterone therapy in RA; it should be individualized. Testosterone levels should be measured to assist in making a clinical decision.

Discussion of the Case History

Mr. L.C. was diagnosed to have a fall risk from his arthritis and muscle wasting. It is an important geriatric medicine principle to prevent falls, as they lead to further morbidity such as pneumonia and incontinence, and even to mortality. As such, physical therapy assessment and treatment is very important. In this case, testosterone enanthate 200 mg IM every 2 weeks was added to the patient’s treatment. The patient returned to the clinic after 6 weeks and said that the pain in his knees had completely disappeared. Testosterone was used with the intent to regain muscle strength, rather than treat his arthritis. Although he was already on Cox-2 inhibitors, the testosterone given could have helped reduced the rheumatoid inflammation in his knee. He surprised the nurses in the clinic by turning up without his walker and needing no assistance in ambulation. He claims that his memory improved, but this was not measurable on the Folstein. His blood pressure and diabetes were also better controlled. Overall, what is most important is that Mr. L.C. achieved a better quality of life. He even reported a return of early morning erections!

Conclusion and Key Points

Many presume that age and rheumatic diseases are linked. Although osteoarthritis is frequent in the elderly, it is not a consequence of aging. Also, elderly men can present with multiple other causes of muscle and joint pain, and suspicion and purposeful evaluation is important to make an adequate diagnosis and establish a treatment. If the diagnosis is not clear or the treatment seems complex or difficult, a consult to a rheumatologist or geriatrician may be needed.

• Osteoarthritis is not a function of aging per se. It may be more common among women because of the predominance of estrogen receptors in bone and cartilage cells that modify the rate of metabolism.

• Although there are no specific treatments for osteoarthritis, exercise plays an important role. Cox-2 inhibitors are recommended for older individuals.

• Seropositive RA does not have a significant predominance among women, as compared with seronegative RA.

• Current thinking is that RA may be more acute in older individuals, and the impact similar to that in younger individuals, and as such should be treated aggressively.

• Ankylosing spondylitis occurs predominantly in men in the third and fourth decades of life.

• Collagen vascular disease and fibromyalgia can occur in men as well.

• There is an association between low testosterone and RA in men.

• Androgens have antiinflammatory properties, whereas estrogens are immunoenhancing. There is complex interplay between androgens and RA.

REFERENCES

1. Demlow L, Liang MH, Eaton HM. Impact of chronic arthritis in the elderly Clin Rheum Dis 1986;12:329–335

2. Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Schappert SM. Magnitude and characteristics of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions on ambulatory medical care visits, United States, 1997. Arthritis Rheum 2002;47:571–581

3. Christmas C, Crespo CJ, Franckowiak SC, et al. How common is hip pain among older adults? Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Fam Pract 2002;51

4. Creamer P, Hochberg MC. Osteoarthritis. Lancet 1997;350: 503–509

5. Hamerman D. Clinical implications of osteoarthritis and ageing. Ann Rheum Dis 1995;54:82–85

6. Berenbaum F, Osteoarthritis A. Epidemiology, pathology and pathogenesis. In: Klippel JH, ed. Primer of Rheumatic Diseases. Atlanta: Arthritis Foundation; 2001

7. Belanger A, Martel L, Berhelot JM, et al. Gender differences in disability-free life expectancy for selected risk factors and chronic conditions in Canada. J Women Aging 2002;14:61–83

8. Hawker GA, Wright JG, Coytre PC, et al. Differences between men and women in the rate of use of hip and knee arthroplasty. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1016–1022

9. Creamer P, Lethbridge-Cejku M, Hochberg MC. Factors associated with functional impairment in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:490–496

10. Schumacher HR Jr. Secondary osteoarthritis. In: Moskowitz Rw, Howell DS, Golberg VM, et al, eds. Osteoarthritis: Diagnosis and Surgical Management. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1993:367–398.

11. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, Brant KD, et al. Guidelines for the medical management of osteoarthritis, Part 1: osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:1535–1540

12. Hochberg MC, Alman RD, Brant KD, et al. Guidelines for the medical management of osteoarthritis, Part II: osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:1541–1546

13. American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis Guidelines. Recommendation for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 update. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:1905–1915

14. AGS Panel on Chronic Pain on Older Persons. Clinical Practice Guidelines: the management of chronic pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998;46:635–651

15. Brandt KD, Smith GN Jr, Simon LS. Intraarticular injection of hyaluronan as treatment for knee osteoarthritis: what is the evidence? Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:1192–1203

16. McAlindon TE, LaValley MP, Guilin JP, Felson DT. Glucosamine and chondroitin for the treatment of osteoarthritis: a systematic quality assessment and meta-analysis. JAMA 2000;283:1469–1475

17. Mavragani CP, Moutsopoulos HM. Rheumatoid arthritis in the elderly. Exp Gerontol 1999;34:463–471

18. Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Rheumatoid arthritis: A: epidemiology, pathology and pathogenesis. In: Klippel JH, Crofford JH, Weyand CM, eds. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases. Atlanta: Arthritis Foundation; 2001

19. Anderson RJ. Rheumatoid arthritis: B: clinical and laboratory features. In: Klippel JH, Crofford JH, Weyand CM, eds. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases. Atlanta: Arthritis Foundation; 2001

20. Van der Heijde DM, van Reil PL, van Leeuwen MA, et al. Prognostic factors for radiographic damage and physical disability in early rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study of 147 patients. Br J Rheumatol 1992;31:519–525

21. Krause D, Schleusser B, Herberon G, et al. Response to methotrexate treatment is associated with reduced mortality in patients with severe rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:14–21

22. Wluka A, Buchbinder R, Mylvaganam A, et al. Long-term methotrexate use in rheumatoid arthritis: 12 year follow-up of 460 patients treated in community practice. J Rheumatol 2000;27:1864–1871

23. O’Dell JR, Haire CE, Erikson N, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with methotrexate alone, sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine, or a combination of all three medications. N Engl J Med 1996;334:1287–1291

24. Boers M, Verhoeven AC, Markusse HM, et al. Randomised comparison of combined step-down prednisolone, methotrexate and sulphasalazine alone in early rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 1997;350:309–318

25. Stand V, Tugwell P, Bombardier C, et al. Function and health-related quality of life: results from a randomized controlled trial of leflunomide vs. methotrexate or placebo in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:1870–1878

26. Weinblatt ME, Keystone EC, Furst DE, et al. Adalimumab, a fully human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in patients taking concomitant methotrexate: the ARMADA trial. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:35–45

27. Pease CT, Bhakta BB, Devlin J, Emery P. Does the age of onset of rheumatoid arthritis influence phenotype?: a prospective study of outcome and prognostic factors. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38:228–234

28. Labbe P, Hardouin P. Epidemiology and optimal management of polymyalgia rheumatica. Drugs Aging 1998;13:109–118

29. Weyand CM, Fulbright JW, Evans JM, et al. Corticosteroid requirements in polymyalgia rheumatica. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:577–584

30. Brack A, Martinez-Taboada V, Stanson A, et al. Disease pattern in cranial and large vessel giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:311–317

31. Wordsworth P. Genes in the spondyloarthropathies. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1998;24:845–863

32. Khan MA. Ankylosing spondylitis: clinical features. In: Klippel JH, Dieppe PA, eds. Rheumatology. 2nd ed. London: Mosby; 1998

33. Amor B, Dougados M, Mijiyama M. Criteres de classification des spondyloarthropaties. Rev Rhum 1990;57:85–89

34. Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Abdellatif M, et al. Comparison of sulfasalazine and placebo for the treatment of axial and peripheral articular manifestations of the seronegative spondyloarthropathies: a Department of Veterans Affairs cooperative study. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:2325–2329

35. Biasi D, Carletto A, Caramaschi P, et al. Efficacy of methotrexate in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a three-year open study. Clin Rheumatol 2000;19:114–117

36. Brandt J, Haibel H, Cornely D, et al. Successful treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with the anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody infliximab. Arthritis Rheum 2000; 43:1346–1352

37. Kimberley RP. Connective-tissue diseases. In: Klippel JH, Crofford JH, Weyand CM, eds. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases. Atlanta: Arthritis Foundation; 2001

38. Baer AN, Pincus T. Occult systemic lupus erythematosus in elderly men. JAMA 1983;249:3350–3352

39. Tishler M, Yaron I, Shirazi I, Yaron M. Clinical and immunological characteristics of elderly onset Sjogren’s syndrome: a comparison with younger onset disease. J Rheumatol 2001; 28:795–797

40. Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia and diffuse pain syndromes. In: Klippel JH, Crofford JH, Weyand CM, eds. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases. Atlanta: Arthritis Foundation; 2001

41. Tengstrand B, Carsltrom K, Hafstrom I. Biovailable testosterone in men with rheumatoid arthritis- high frequency of hypogonadism. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002; 41: 285–289

42. Cutolo M. Sex hormone adjuvant therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2000;26:881–895

43. Kelce WR, Stone CR, Laws SC, et al. Persistent DDT metabolite p,p-DDE is a potent androgen receptor antagonist. Nature 1995;375:581–585

44. Da Silva JA, Larbre JP, Seed M, et al. Sex differences in inflammation induced cartilage damage in rodents. J Rheumatol 1994;21:330–337

45. Steward A, Bayley DI. Effects of androgens in models of rheumatoid arthritis. Agents Actions 1992;35:268–272

46. John S, Myerscough A, Eyre S, et al. Linkage of a marker in intron D of the estrogen synthase locus to rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:1617–1620

47. Huyser B, Parker JC. Stress and rheumatoid arthritis: an integrative review. Arthritis Care Res 1998;11:135–145

48. Hall GM, Larbre JP, Spector TD, et al. A randomized trial of testosterone therapy in males with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 1996;35:568–573

49. Cutolo M, Balleari E, Giusti M, et al. Androgen replacement therapy in male patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1991;34:1–5

50. Martens HF, Sheets PK, Tenover JS, et al. Decreased testosterone levels in men with rheumatoid arthritis: effect of low dose prednisone therapy. J Rheumatol 1994; 21:1427–1431

< div class='tao-gold-member'>