Chapter 63 ANTERIOR COLPORRHAPHY FOR CYSTOCELE REPAIR

Pelvic organ prolapse is common in women. The anterior wall of the vagina primarily provides support for the bladder and urethra. If the support for the bladder sags, a cystocele results. The lifetime risk of undergoing an operation for prolapse or urinary incontinence has been estimated to be 11.1%.1 Of the women undergoing surgery for prolapse with and without urinary incontinence, 48% had an anterior colporrhaphy included in their surgical management. This chapter discusses the anatomy and possible causes of anterior wall prolapse. A discussion of an anterior colporrhaphy for surgical repair of a cystocele is presented.

ANATOMY AND PATHOLOGY

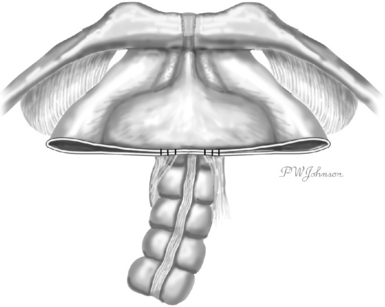

The anterior vaginal wall is the trapezoid of fibromuscularis and provides support to the bladder and urethra. At the apex, the broad portion of the trapezoid, the anterior vaginal wall has suspensory support provided by the cardinal-uterosacral ligaments. The lateral support is provided by a condensation of connective tissue over the levator ani muscles, the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis. The arcus tendineus fascia pelvis extends from the posterior, inferior aspect of the pubic bone to the ischial spine (Fig. 63-1). Nichols and Randall proposed that a cystocele is an end result of either distention (overstretching of the fibromuscularis of the anterior vaginal wall) or displacement (breaks in the connective tissue).2 In 1976, A. Cullen Richardson popularized the “site-specific” approach to identifying specific breaks in the connective tissue and repairing those defects.3

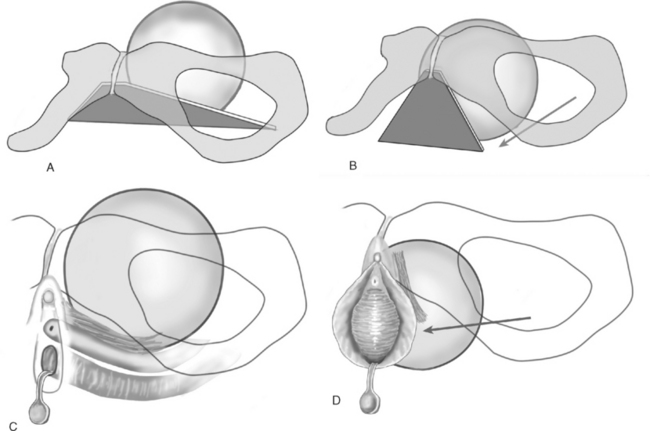

Apical loss of support of the anterior vaginal wall may occur with an apical, transverse separation of the anterior vaginal fibromuscularis with the cardinal-uterosacral ligaments. As abdominal pressure is placed on the lateral connective tissue attachments, these attachments may fail, allowing the anterior vaginal wall to swing toward the hymen (Fig. 63-2). John DeLancey made surgical observations in 71 women undergoing a retropubic procedure for anterior wall prolapse and stress urinary incontinence.4 He found that 88.7% of these women had a paravaginal defect and that the area of detachment was at the apex near the ischial spine. Detachment from the back of the pubic bone was rare. Although the majority of women with anterior wall prolapse and stress urinary incontinence may have a paravaginal loss of connective tissue support, the support for the anterior wall of the vagina is much more complex than a list of fascial attachments.

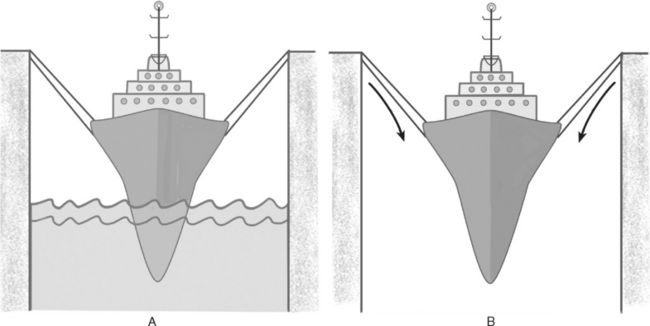

The support for the pelvic organs is maintained by the interaction of connective tissue attachments and innervated, intact pelvic floor musculature. The levator ani muscles provide the primary support for the pelvic floor. The pelvic organs are supported within the abdominal cavity, and the levator hiatus, through which the urethra, vagina, and rectum pass, is closed. The etiology of pelvic organ prolapse is thought to be multifactorial, including abnormalities of connective tissue, pelvic floor muscles, and/or the innervation to the pelvic floor. Norton5 used the analogy of a boat in a dry dock to describe the interplay of the functioning pelvic floor and connective tissue supports (Fig. 63-3). The pelvic floor muscles (primarily the levator ani muscles) play the supporting role of the water. When the water level is adequate, little stress is placed on the ropes (connective tissue supports) keeping the boat in place. However, if the water level is dropped, the ropes will not be able to hold the boat for long. If the levator ani muscles no longer are able to maintain a closed levator hiatus, the stress of maintaining the pelvic organs is placed on the connective tissue supports. Direct damage to the levator ani muscle or to its innervation may open the hiatus and place the burden of support on the connective tissue of the pelvic organs. Prior damage to the connective tissue support of the anterior vaginal wall may be evident only in light of the loss of levator ani function.

DeLancey and Hurd clinically determined that the levator hiatus is larger in women with prolapse than in those without prolapse.6 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed that the size of the levator hiatus and levator symphysis gap increases with increasing stage of prolapse.7 Lennox Hoyte and colleagues evaluated the change in morphology of the levator ani muscles with two- and three-dimensional MRI images.8 They demonstrated that women with prolapse have significantly more levator ani degradation, laxity, and loss of the integrity of the sling portion of the levator ani compared with asymptomatic controls. This change may be occur as a result of direct muscle damage associated with childbirth or chronic straining or damage to the innervation of the pelvic floor.

Abnormalities in the histology of connective tissue have also been described in women with prolapse. Abnormalities of collagen synthesis may derive from an intrinsic abnormality of collagen synthesis (due to abnormal collagen, an imbalance between synthesis and degradation, or an imbalance between collagen types). The environment (e.g., excessive straining) may also contribute to the condition of the connective tissue. Error in the repair of damaged ligaments and fascia or lack of remodeling in mature collagen may occur. Dietz and colleagues examined bladder neck descent in nulliparous twins.9 A significant genetic contribution was proposed to contribute to the phenotype of the bladder neck mobility.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

A woman with anterior wall prolapse may be asymptomatic, or she may present with symptoms related to a vaginal mass with or without changes in sexual and urinary function. Pelvic pressure, heaviness, or a bulge may occur. Women often feel that their symptoms are more significant as the day progresses and gravity allows the prolapse to fully descend. The bladder follows the anterior vaginal wall as it descends through the genital hiatus in women with an anterior wall bulge. Because the distal urethra remains fixed under the pubic symphysis, voiding difficulties due to obstruction may arise. Women who have to manually reduce their prolapse to empty their bladder are likely to have more significant prolapse than those who do not.10 This obstructive effect on the urethra may protect a woman from leaking urine with abdominal stress (occult incontinence). Women with anterior wall prolapse extending more than 1 cm beyond the hymen are less likely to describe stress urinary incontinence than those will lesser prolapse.10 Sexual function has also been examined in women with prolapse and appears to be similar to that in women without prolapse.10,11

The goal of the physical examination is to recreate the woman’s symptoms. A validated measure of pelvic organ prolapse is the pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POPQ) method.12 Measurement of the descent of the anterior vaginal wall is made at maximal strain. If a woman describes prolapse more significant than that observed in the supine or sitting positions, a standing examination may be employed. The woman’s position and the degree of bladder distention (empty or full) should be documented. A full bladder may help to recreate the patient’s most prominent symptoms of vaginal bulging.

Bob Shull described a method to evaluate the anterior vagina for site-specific defects.13 Curved ring forceps are placed in the vagina, supporting the lateral anterior vaginal wall to the ischial spine. The patient is asked to bear down in a Valsalva maneuver. If the anterior vaginal wall prolapse is reduced, a paravaginal defect is diagnosed. A bilateral and a unilateral paravaginal defect may be differentiated with alternating unilateral paravaginal support. If the anterior vaginal wall continues to balloon forward despite paravaginal support, a midline defect is diagnosed. A superior or high transverse defect may be suspected if the prolapse is reduced with apical support. Loss of rugation at one of these sites is also thought to be associated with localization of the defect. Whiteside and colleagues evaluated the inter-examiner and intra-examiner reliability of site-specific defect examination.14 They found that there was poor examiner concordance for the presence of superior, paravaginal, or central defects. Not surprising is that the reliability of the examination increased with stage of prolapse.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree