Anatomy and Pathophysiology of Hernias

Daniel J. Scott

Luisangel A. Rondon

Introduction

The repair of an abdominal wall hernia represents one of the most frequent procedures performed by general surgeons. In 2006, more than 1.1 million hernia repairs were performed in the United States.

An abdominal hernia is a defect in the wall of the abdominal cavity that allows protrusion of an organ or abdominal content through it. These defects most commonly involve the anterior abdominal wall, particularly at sites considered weak as the inguinal, femoral, and umbilical areas. The groin represents the area where the majority of abdominal wall hernias occur, totaling approximately 75% of the total incidence.

Anterolateral Abdominal Wall

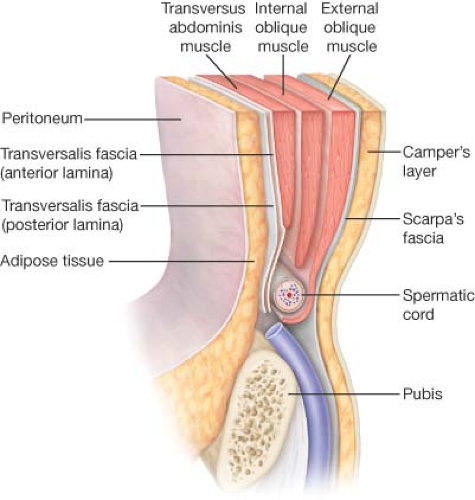

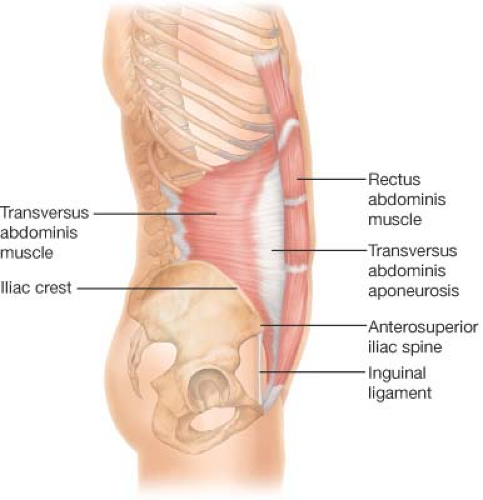

Containing most of the abdominal viscera, the abdominal wall forms a flexible and deformable girth that extends over the bony framework of the lumbar spine posteriorly, the pelvis inferiorly, and the costal margin superiorly. Though it is primarily formed by muscle and aponeurosis, the lateral abdominal wall consists of at least nine layers placed one on the other. From superficial to deep, it includes skin, Camper’s fascia, Scarpa’s fascia, the external oblique aponeurosis and muscle, the internal oblique aponeurosis and muscle, the transversus abdominis aponeurosis and muscle, the transversalis fascia, the preperitoneal fat, and the peritoneum (Fig. 1.1). These layers continue in the region of the groin as they form their insertions in the inguinal canal. Medially, the rectus abdominis muscle forms a major component.

The groin represents the portion of the anterolateral abdominal wall below the level of the anterior superior iliac spines formed by the inferior insertion of the lateral oblique muscles surrounding the inguinal canal on both sides of the pubis.

Camper’s Fascia

This is a thick superficial layer that contains the bulk of fat in the lower abdominal wall that blends with the reticular layer of the dermis. Its thickness varies with the body composition of the person. This layer, which is continuous with the corresponding

layers covering the perineum and genitalia, also contains the dartos muscle fibers of the scrotum. The major blood vessels of this layer are the superficial epigastric vessels and superficial circumflex iliac vessels, tributaries of the femoral vessels.

layers covering the perineum and genitalia, also contains the dartos muscle fibers of the scrotum. The major blood vessels of this layer are the superficial epigastric vessels and superficial circumflex iliac vessels, tributaries of the femoral vessels.

Scarpa’s Fascia

Scarpa’s fascia is a homogeneous membranous sheet of areolar tissue that forms a lamina in the depths of the subcutaneous tissues and usually is most prominent in the region of the groin. It is loosely connected to the external oblique muscle, but in the midline it is more intimately adherent to the linea alba and to the pubic symphysis, and is prolonged onto the dorsum of the penis, forming the fundiform ligament (suspensory ligament of the clitoris in females); below and laterally, it blends with the fascia lata of the thigh.

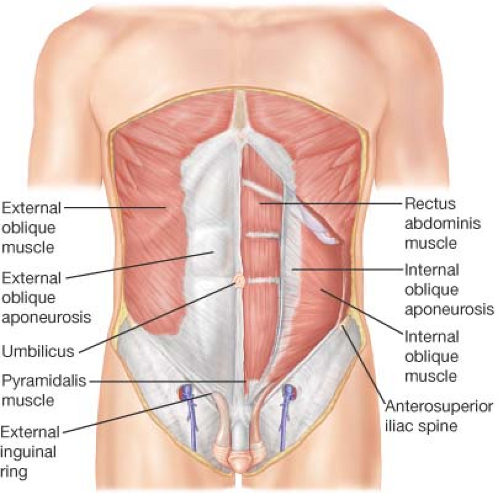

External Oblique Muscle and Aponeurosis

The external oblique muscle is the most superficial of the three flat musculoaponeurotic layers that make up the anterolateral wall of the abdomen. It is directed inferiorly and medially extending from the posterior aspects of the lower eight ribs to the linea alba, the pubis, and the iliac crest (Fig. 1.2). Medially, the tendinous fibers pass anterior to the rectus abdominis muscle, forming the anterior layer of the rectus sheath.

Below the anterior superior iliac spine, the external oblique muscle is wholly aponeurotic and therefore, in the groin region, there is no external oblique muscle, only aponeurosis. The anteroinferior fibers of insertion of the external oblique aponeurosis fold on themselves to form the inguinal ligament. Inferiorly, the aponeurotic insertions into the body of the pubis and the pubic tubercle form the superficial or external inguinal ring, a triangular opening through which the spermatic cord or round ligament passes.

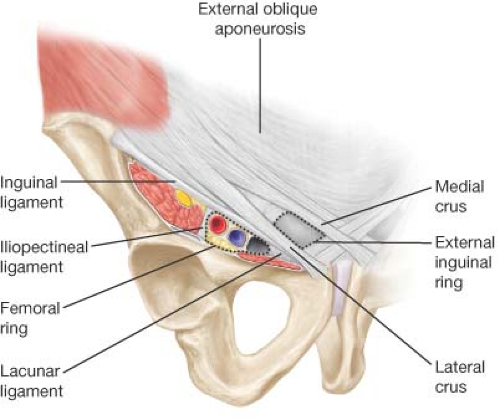

Inguinal Ligament

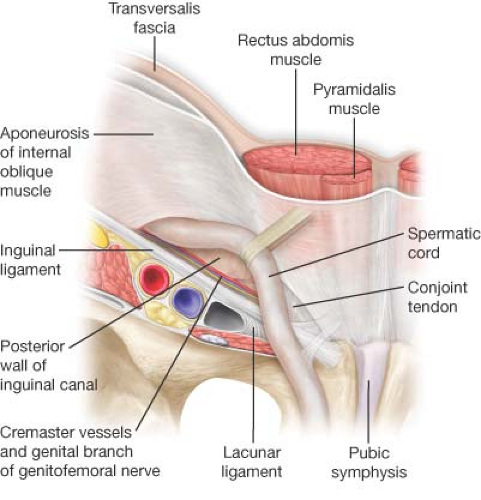

The inguinal ligament is the lower, thickened portion of the external oblique aponeurosis suspended between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle. The fibers of the external oblique aponeurosis that form the inguinal ligament present a rounded surface toward the thigh and a hollow surface toward the inguinal canal functioning as a supporting shelf for the spermatic cord (Fig. 1.3).

Lacunar Ligament

First described by Antonio de Gimbernat in 1793, the lacunar ligament is a triangular extension of the inguinal ligament before its insertion upon the pubic tubercle. It is inserted at the pecten pubis, and its lateral end meets the proximal end of the ligament of Cooper. It is considered the medial border of the femoral canal (Fig. 1.3).

External Inguinal Ring

The superficial or external inguinal ring is located above the superior border of the pubis, immediately lateral to the pubic tubercle. It is a triangular opening of the aponeurosis of the external oblique, the base being part of the pubic crest with the margins formed by two crura, medial and lateral. The medial crus is formed by the aponeurosis of the external oblique itself; the lateral crus is formed by the inguinal ligament. To be more specific, the medial crus is attached to the lateral border of the rectus sheath and to the tendon of the rectus abdominis muscle. The lateral crus is attached to the pubic tubercle (Fig. 1.3).

Internal Oblique Muscle and Aponeurosis

The internal oblique muscle and aponeurosis represent the middle layer of the three flat musculoaponeurotic layers of the abdominal wall. The internal oblique muscle arises in part from the thoracolumbar fascia and the iliac crest splaying obliquely upward, forward, and medially to insert upon the inferior borders of the lower three or four ribs, the linea alba and the pubis (Fig. 1.2).

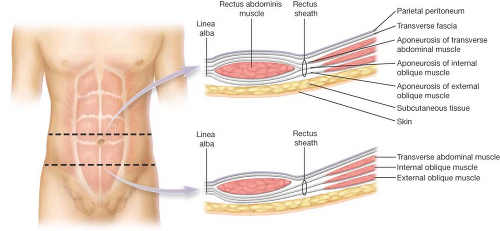

The aponeurosis of the internal oblique above the level of the umbilicus splits to envelop the rectus abdominis, re-forming in the midline to join and interweave with the fibers of the linea alba. Below the level of the umbilicus, the aponeurosis does not split but rather runs only anterior to the rectus muscle (Fig. 1.4).

The lowest fibers of the internal oblique muscle arch over the spermatic cord or the round ligament. Medially, the lower border of this muscular arch is usually at or slightly above the level of the aponeurotic arch of the underlying transversus abdominis layer. Some of the lower muscle bundles in the male form the cremaster muscle fibers that invest the spermatic cord.

The internal oblique layer is mainly muscular in the inguinal region and throughout much of its course in the groin, it is intimately attached to the underlying fibers of the transversus abdominis aponeurosis. The aponeurotic continuation of these lower bundles of the internal oblique usually is directed transversely to the linea alba and slightly more inferiorly inserted to the body of the pubis.

Transversus Abdominis Muscle and Aponeurosis

The transversus abdominis muscle and aponeurosis are the deepest of the three flat anterior abdominal muscles layers. These layers arise from the fascia along the iliac crest, thoracolumbar fascia, iliopsoas fascia, and from the lower six costal cartilages and ribs (Fig. 1.5).

The muscle bundles of the transversus abdominis course horizontally except the inferior border of the transversus abdominis layer that forms a curved line, the transversus abdominis arch (Fig. 1.6), an important landmark for the surgeon because it represents the superior border of the direct inguinal hernia space. The area beneath the arch and the number of aponeurotic fibers and strength in this lower portion of the transversus abdominis lamina varies, having a major influence in the development of a direct inguinal hernia.

The aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis joins the posterior lamina of the internal oblique forming part of the posterior rectus sheath above the umbilicus. Below the umbilicus, the transversus abdominis aponeurosis is a component of the anterior rectus sheath. The gradual termination of aponeurotic tissue on the posterior aspect of the rectus abdominis muscle forms the arcuate line of Douglas.

The medial aponeurotic fibers of the transversus abdominis insert on the pectin pubis and the crest of the pubis to form the ligament of Henle or falx inguinalis (Fig. 1.6). The falx inguinalis has an intimate relation with the rectus sheath consisting of the dense insertion of the transversus aponeurosis lateral to the tendon and muscular belly of the rectus muscle. Rarely, the fibers of the transversus abdominis aponeurosis are joined in this area by fibers from the internal oblique aponeurosis to form a true conjoined tendon.

Conjoined Tendon

The conjoined tendon is, by definition, the fusion of lower fibers of the internal oblique aponeurosis with similar fibers from the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis where they insert on the pubic tubercle and superior ramus of the pubis. A true conjoined tendon is considered rare, according to Condon present in 3% of cases and believed by McVay to be only an artifact of dissection.

Rectus Abdominis Muscle

The rectus abdominis forms the central and anchoring muscle mass of the anterior abdomen. The rectus abdominis muscle attaches to the fifth, sixth, and seventh costal cartilages and the xiphoid process above. Below, it attaches to the pubic crest, symphysis pubis, and the superior ramus of the pubis. Each rectus muscle is traversed by tendinous intersections at the level of the xiphoid process, the mid-upper abdomen, and at the umbilicus.

The rectus muscle is enclosed within a stout sheath formed by the aponeuroses of the three flat muscles that divide and pass anteriorly and posteriorly around the muscle. From the rib margin to a point midway between the umbilicus and the pubis (arcuate line of Douglas), the posterior sheath is made up of the posterior leaf of the internal oblique aponeurosis, the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis muscle, and the transversalis fascia. Below this level, the posterior wall is formed by transversalis fascia alone, with variable contributions of aponeurotic bands from the transversus abdominis (Fig. 1.4). The deep epigastric arteries and veins course along the posterior surface of the rectus muscle, so below the arcuate line they are separated from the peritoneum only by transversalis fascia.

Medially, the two recti are separated by the linea alba, a tendinous line wherein the aponeuroses of the three flat muscles fuse with and decussate across the midline.

Transversalis Fascia

The transversalis fascia is a portion of the continuous layer of the endoabdominal fascia that completely encloses the abdominal cavity. In various areas, the endoabdominal fascia is given particular regional designations derived from the overlying muscles, in this instance, the transversus abdominis muscle. The transversalis fascia is immediately continuous with the lumbar, iliac, psoas, and obturator fasciae. It continues medially as the rectus fascia, forming a posterior covering of the lower part of the rectus muscle.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree