Chapter 35 Ampullary Neoplasia

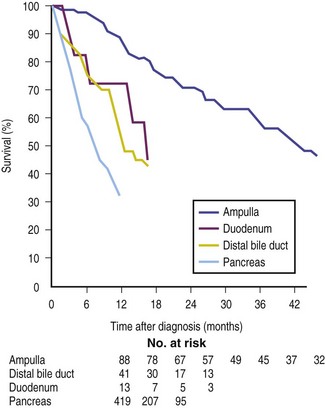

Malignant tumors of the ampulla of Vater are uncommon. Less than 1 in 50,000 people over age 40 are diagnosed with ampullary malignancy each year.1 Much more common is a heterogeneous group of malignancies occurring in the periampullary region, including tumors of the adjacent part of the pancreatic head, the distal common bile duct, adjacent duodenal mucosa, and the ampulla of Vater. Prior to surgical resection the exact origin of a periampullary tumor is often not clear. However, the tissue of origin has important prognostic implications, with tumors arising from the pancreas carrying a worse prognosis (Fig. 35.1).2 Conversely, tumors in this region often present relatively early due to biliary and/or pancreatic obstruction and have a better prognosis. An autopsy series from the Mayo Clinic reported 25 periampullary lesions out of 4000 consecutive autopsies (0.6%) and at most only 20% of these lesions were symptomatic.3

Fig. 35.1 Survival curves for 561 patients with periampullary tumors, stratified by site of origin.

(Reproduced with permission from Bettschart V, Rahman MQ, Engleken FJ, et al. Presentation treatment and outcome in patients with ampullary tumors. Br J Surg. 2004;91[12]:1600-1607.)

The most common benign tumor of the ampulla of Vater is an adenoma. An adenoma-carcinoma sequence analogous to what occurs in the colon exists and therefore all adenomas should be considered for resection. Many adenomas will be suitable for endoscopic resection (see Chapter 24). However, adenomas extending well into the ductal system or lesions with malignant transformation usually require pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure). This chapter discusses lesions arising from the ampulla.

Symptoms and Signs

Fortunately, patients with ampullary lesions often develop symptoms and signs relatively early in the course of the disease. This is the result of the lesion arising from the junction of the pancreatic and bile ducts, thus impeding flow of bile and/or pancreatic secretions. Jaundice is the presenting symptom in the majority of patients. Unlike patients with pancreatic head malignancy, jaundice may initially be intermittent. Biliary obstruction may also be associated with signs and symptoms of cholangitis. In addition, nonspecific symptoms such as weight loss, abdominal discomfort, nausea, and vomiting may be seen. Obstructive jaundice, anemia due to blood loss, and a palpable gallbladder* make up the classic triad of ampullary cancer, though this is seen in a small minority of patients.

1. Surveillance for duodenal/ampullary lesions in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) syndrome.

2. Incidental lesions discovered at upper endoscopy.

3. Investigation of biliary dilation where imaging was performed for an unrelated indication (see Chapter 33).

In an endoscopic series of 55 ampullary adenomas, 45% were asymptomatic, 16% had abdominal pain, 15% had jaundice, 9% had pancreatitis, and 15% had miscellaneous symptoms.4

Presentation with severe gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is uncommon but has been described with ampullary adenomas, carcinomas, metastatic malignancy, and mesenchymal tumors. In all cases they result from necrosis and ulceration of the overlying mucosa.5

There are no specific laboratory findings associated with ampullary tumors. Biliary obstruction results in elevation of alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, and eventually bilirubin. Transaminases may also be elevated, especially in the setting of acute obstruction or cholangitis. Tumor markers have little role but may be useful for prognostic purposes. Serum CA 19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels have sensitivities for ampullary adenocarcinoma of 78% and 33%, respectively. The specificity of both markers is low.6

Diagnostic Workup and Evaluation

Endoscopy

For complete endoscopic assessment of the ampulla the examination must be done with a duodenoscope. Examination with an end-viewing endoscope will cause a significant proportion of abnormalities to be missed. Two recent studies have demonstrated that duodenoscopy with a forward-viewing endoscope missed 50% of gross lesions visible with the side-viewing endoscope.7,8 Endoscopy usually allows diagnosis of ampullary tumors as well as providing information regarding degree of lateral spread. A wide variation exists in the appearance of the ampulla, which often appears quite villiform. Endoscopy permits biopsy of the ampulla, although in one study endoscopic biopsy failed to diagnose deeper malignancy in 7 of 23 cases.9 Furthermore, care should be taken to avoid direct biopsy of the papillary orifice, as even cold biopsy has been associated with acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Biopsies from the interior of a biliary sphincterotomy may diagnose ampullary pathology more accurately.

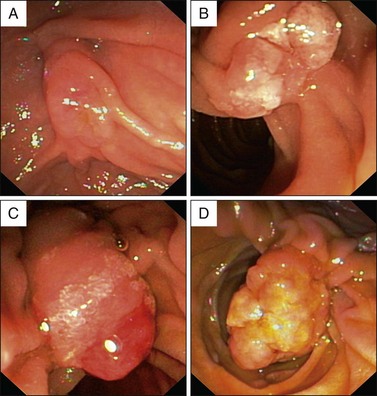

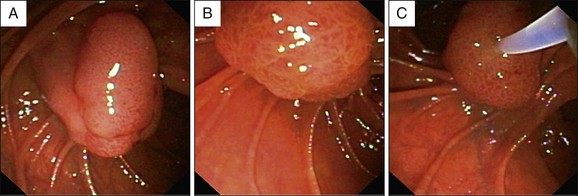

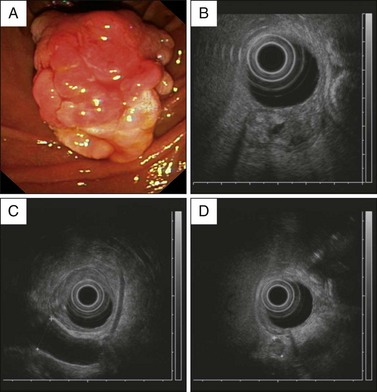

Macroscopically, ampullary masses conform to one of four well-recognized variations (Figs. 35.2 and 35.3):

Macroscopically normal papilla: Suspicion of an ampullary lesion is usually due to pancreatic and biliary ductal dilation down to the level of the duodenal wall on cross-sectional imaging (see Chapters 33 and 34). Completely intraampullary neoplasms may become apparent only when a sphincterotomy is performed but may also be well visualized with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS).

Macroscopically normal papilla: Suspicion of an ampullary lesion is usually due to pancreatic and biliary ductal dilation down to the level of the duodenal wall on cross-sectional imaging (see Chapters 33 and 34). Completely intraampullary neoplasms may become apparent only when a sphincterotomy is performed but may also be well visualized with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS).

Intramural protrusion: A bulge underneath a normal-appearing papilla (“prominent infundibulum”). The differential diagnosis of this appearance also includes type III choledochal cyst and impacted biliary or pancreatic duct stones.

Intramural protrusion: A bulge underneath a normal-appearing papilla (“prominent infundibulum”). The differential diagnosis of this appearance also includes type III choledochal cyst and impacted biliary or pancreatic duct stones.

Exposed protrusion: Neoplastic-appearing tissue extending out from the papilla.

Exposed protrusion: Neoplastic-appearing tissue extending out from the papilla.

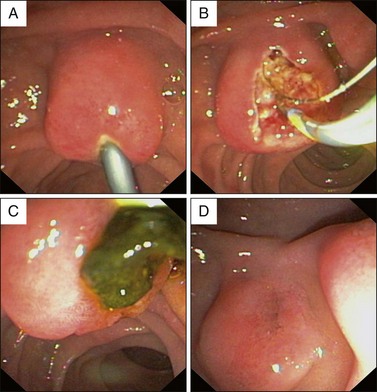

Ulcerating tumor: This situation is suspicious for malignancy (see Fig 35.4, A). Another feature suggestive of malignancy is failure of the lesion to lift when a submucosal injection is performed (sometimes included in the technique of endoscopic ampullectomy; see Chapter 24).10 Other features suggesting malignancy include friability and induration.

Ulcerating tumor: This situation is suspicious for malignancy (see Fig 35.4, A). Another feature suggestive of malignancy is failure of the lesion to lift when a submucosal injection is performed (sometimes included in the technique of endoscopic ampullectomy; see Chapter 24).10 Other features suggesting malignancy include friability and induration.

In a series of 52 cases of adenomas or carcinomas, Ponchon and co-workers noted an endoscopically normal–appearing ampulla in 37%.11 In these cases an underlying tumor became evident only after biliary sphincterotomy.

ERCP

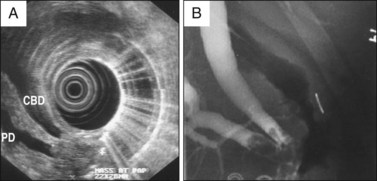

The introduction of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and EUS has lessened the diagnostic role for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Nonetheless, ERCP continues to play an important therapeutic role in establishing biliary drainage, often accompanied by diagnostic biopsy. Biliary sphincterotomy permits deeper tissue sampling as well as targeted biopsies from the pancreatic orifice. Sphincterotomy is also used as part of the ampullectomy technique, either to inferiorly displace a small lesion away from the ductal orifice prior to snare removal or to prevent papillectomy stenosis. Cholangiography remains an important tool to assess intraductal extension of a tumor (Fig. 35.5).12

Forceps Biopsy

Endoscopic forceps biopsy, taken from the surface of an ampullary lesion, is the usual mode of diagnosis. However, these biopsies can have a significant false-negative rate for malignancy.9 To reduce sampling error it is recommended that at least six biopsies should be obtained, taking care to avoid the pancreatic orifice. Malignant change within an ampullary adenoma may be seen in up to 30%, and in up to 50% in older series.9,13 Despite these limitations, recent series of endoscopic management of ampullary adenomas have quoted a malignancy rate of only 6% to 8% of ampullectomy specimens presumed to have benign disease.12,14 This change is probably related to improved staging prior to endoscopic papillectomy and surgical ampullectomy. As mentioned above, biopsies obtained from within a sphincterotomy may have a higher yield for malignancy. The best yield of biopsy is seen when the sample is obtained at least 10 days after sphincterotomy when diathermy artifact has cleared.15 EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration may be useful in the assessment of ampullary masses with a reported sensitivity and specificity of 82% and 100%, respectively,16 though further data on the role of EUS tissue sampling are required.

Transabdominal Ultrasound, CT, and MRI

Obstructive jaundice is often initially investigated with transabdominal ultrasound (US) due to its accessibility, cost, and safety. In the case of obstruction due to an ampullary lesion the common finding is dilation of the entire biliary tree down to the duodenal wall. The tumor itself is not usually visualized. Similarly, the overall sensitivity for computed tomography (CT) is relatively low at 20% to 30% but is higher in the presence of larger tumors.17–19 If a mass is not seen, EUS may be considered, with or without ERCP, depending on whether there is a need to relieve biliary obstruction. CT is a useful staging tool, both for local staging (e.g., vascular involvement) and for distant metastases.20 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and MRCP have not been extensively investigated for ampullary lesions but appear to be promising alternatives to EUS.21

Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS)

EUS may be used for different purposes in the setting of ampullary neoplasia:

1. Diagnosis. EUS has a role in diagnosing patients with obstructive jaundice without a visible mass by transabdominal US or CT. EUS has been shown to be superior to US and CT for the detection of ampullary lesions (95% versus 15% and 20% to 30%, respectively).17–19 However, the ampulla is usually hypoechoic and small lesions (<10 mm) may be missed with EUS.18

As well, EUS can be used in the investigation of an abnormal-appearing ampulla seen at endoscopy. The limited literature on this subject suggests that the specificity of EUS in this setting is about 75%.22 False positives arise from an inflamed and swollen ampulla, possibly due to the recent passage of a calculus (Fig. 35.4). In summary, EUS should be considered an important tool in clarifying the presence of an abnormal-appearing ampulla but the diagnosis rests on tissue confirmation.

2. Staging advanced ampullary cancer. EUS is helpful in staging ampullary malignancy according to the TNM staging system (Box 35.1). Compared to CT and MRI, EUS is the most accurate tool for preoperative T-staging.19,23 In the largest series of 50 patients, EUS was found to be more accurate (87%) compared to CT (24%) and MRI (46%) based on surgical and pathologic T-staging. The main limitation of EUS is in differentiating T2 and T3 lesions. Peritumoral pancreatitis may lead to overstaging a T2 lesion. Similarly, the presence of a biliary stent may lead to inflammatory changes making T-staging more difficult. From a clinical perspective this is not a critical issue since the surgical management of T2 and T3 lesions is identical.

Box 35.1

TNM Staging System for Ampullary Carcinomas

| T1 | Tumor limited to the ampulla of Vater* |

| T2 | Tumor invades duodenal wall (muscularis propria) |

| T3 | Tumor invasion into the pancreas <2 cm |

| T4 | Tumor invasion into the pancreas >2 cm or into adjacent organs or vessels |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis |

*Some divide T1 tumors into d0 (limited to Oddi’s sphincter) and d1 (tumor invading the duodenal submucosa).

From Sobin LH, Wittekind CH, eds. International union against cancer (UICC): the TNM classification of malignant tumors. 6th ed, New York: Wiley; 2002.

N-stage accuracy has not been reported to be different between EUS, CT, and MRI. Metastatic regional nodes are detected by EUS with an accuracy of about 65% (Fig. 35.6).23,24 Locoregional lymph node involvement usually does not influence surgical management.

Surgical resectability depends mainly on vascular involvement and the presence of distant metastases. Due to the early presentation of ampullary tumors and relative distance from the mesenteric vessels, vascular involvement is uncommon. EUS is an accurate means of assessing vascular involvement25,26 and can allow imaging of the portal venous system from the proximal duodenum and of the celiac vessels from the gastric fundus.

3. Staging early ampullary lesions. When local endoscopic or surgical intervention is being considered, accurate T-staging is of vital importance. Endoscopic resection is generally limited to premalignant lesions since early cancers have a 10% to 45% risk of lymph node metastases27 and should be managed with radical resection (Whipple procedure) in operable patients. EUS relies on infiltration and destruction of normal tissue planes to differentiate benign from malignant disease. In the case of benign biopsies, the role of EUS is to exclude an infiltrative lesion deep to the endoscopically visible part of the lesion. The accuracy of EUS to distinguish lesions >T1 stage is high, between 87% and 95%.18,23,25,28 T1 tumors have further been subclassified into T1d0 (limited to the sphincter of Oddi) and T1d1 (invasion of the duodenal mucosa). Local resection is appropriate if the lesion is T1d0 and there is no evidence of malignancy. For the d0/d1 subgrouping, intraductal ultrasound (IDUS) appears to have the best accuracy (see below) but is not readily available.

4. Extension of tissue into the distal bile duct or pancreatic duct is a relative contraindication for endoscopic resection. This may be assessed by carefully performed ERCP or EUS (Fig. 35.5).

Intraductal Ultrasound (IDUS)

IDUS is a promising tool for the staging of ampullary and biliary tumors. Following cannulation of the bile duct at ERCP a 7 Fr ultrasound catheter is advanced over a guidewire into the ductal system. These catheters are reusable rotating mechanical probes that operate at relatively high frequency (12 or 20 MHz) to produce high-quality near-field images but with limited depth. In the largest prospective study on this subject, IDUS was superior to CT and EUS in terms of tumor visualization, especially in detecting small lesions.18 IDUS is the only imaging modality that demonstrates the sphincter of Oddi as a distinct structure.28 Clearly IDUS has the potential to play a large role in selection of patients for endoscopic resection, but further prospective studies are required.

Colonoscopy

Ampullary adenoma may be the presenting feature of attenuated FAP syndrome. Furthermore, there are reports of patients with ampullary adenomata being at increased risk of colonic neoplasia, even in the absence of FAP syndrome.29–31 Ponchon’s group has described colonic polyps in 50% of their patients with sporadic ampullary adenomas, including one with eight polyps and another with a sigmoid malignancy.32 Although these studies are small, it seems prudent to perform colonoscopy in all patients diagnosed with ampullary adenomas and carcinomas, especially prior to surgical resection of the ampullary lesion.

Pathology

Ninety-five percent of neoplasms of the ampulla consist of adenomas or adenocarcinomas. Ampullary tumors are increasingly recognized as sporadic lesions (i.e., not associated with hereditary neoplastic condition; see Fig. 35.2 and Box 35.2) and these probably account for more than 50% of ampullary adenomas and carcinomas. There is a wide range of other benign and malignant neoplastic conditions that can affect the ampulla of Vater. These are listed in Boxes 35.3 and 35.4 (see also Chapter 24). Below, the most common conditions are described in further detail.

Box 35.2

Cancer Syndromes Associated with Ampullary Carcinoma

*Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma (HNPCC) is weakly associated with ampullary carcinoma.

†Neurofibromatosis seems to be a predisposition of both somatostatinomas and carcinomas of the ampulla of Vater.

‡Muir-Torre syndrome is a condition characterized by the association of multiple sebaceous tumors and keratoacanthomas with internal malignancies, including ampullary carcinomas.